The future was up for grabs when the new millennium turned over, and it was also prone to glitches. Although the looming Y2K bug that had threatened to derail technology failed to materialize, that fall's presidential election hung in the balance partially due to "hanging chads." The future of music, too, was anyone’s guess. CD sales reached an all-time peak at the same moment major labels were worrying about Napster destroying their business. Throughout 2000, *NSYNC, Eminem, and Santana sat on top of the charts -- but, for one glorious week in October, so did Radiohead.

Thom Yorke and co. could do no wrong back then, and their opinion was (and still is) received as truth among a not-insubstantial set of fans. One of the bands they took on tour with them that year was Clinic, whom they had first heard on John Peel's radio show. In interviews, members of Radiohead would mention the Liverpool foursome as a current favorite, and that endorsement followed Clinic for a long while -- certainly long enough to buoy their debut album, Internal Wrangler, which dropped in the UK 20 years ago today. (The official US release didn’t happen until the following year, well after Kid A dropped, by which point praise from Radiohead carried an added implication.)

One of the best guitar bands going had deliberately dialed back the guitars, and Yorke's fondness for the Warp Records roster was now common knowledge. If he was also listening to Clinic, there must be something très moderne about them as well. Although the shock of the new dulled with each successive album after it, that energy was definitely coursing through Internal Wrangler. Turns out this was not just a function of hype: Twenty years on, the album can still spark that eureka feeling. A funny thing about the Y2K bug: It made a return earlier this year. It’s hard to predict what is going to have continued relevance -- case in point, those surgical masks that Clinic never left home without.

If Kid A had a way of bringing the future into focus, Internal Wrangler had a way of throwing it into ecstatic disarray. Radiohead had impeccable taste in the sounds of the present. Clinic were reluctant to glean much from their immediate peers. "The last time I thought there was any kind of [British music] worth paying attention to were bands like the Happy Mondays and the Stone Roses," frontman Ade Blackburn told Alternative Press in late 2001. In that regard, their attitude towards the past wasn't diametrically opposed to that of, say, Oasis and other retro-minded artists of the era. But the influences they chose, the riffs they pinched, and how they bent them felt miles apart.

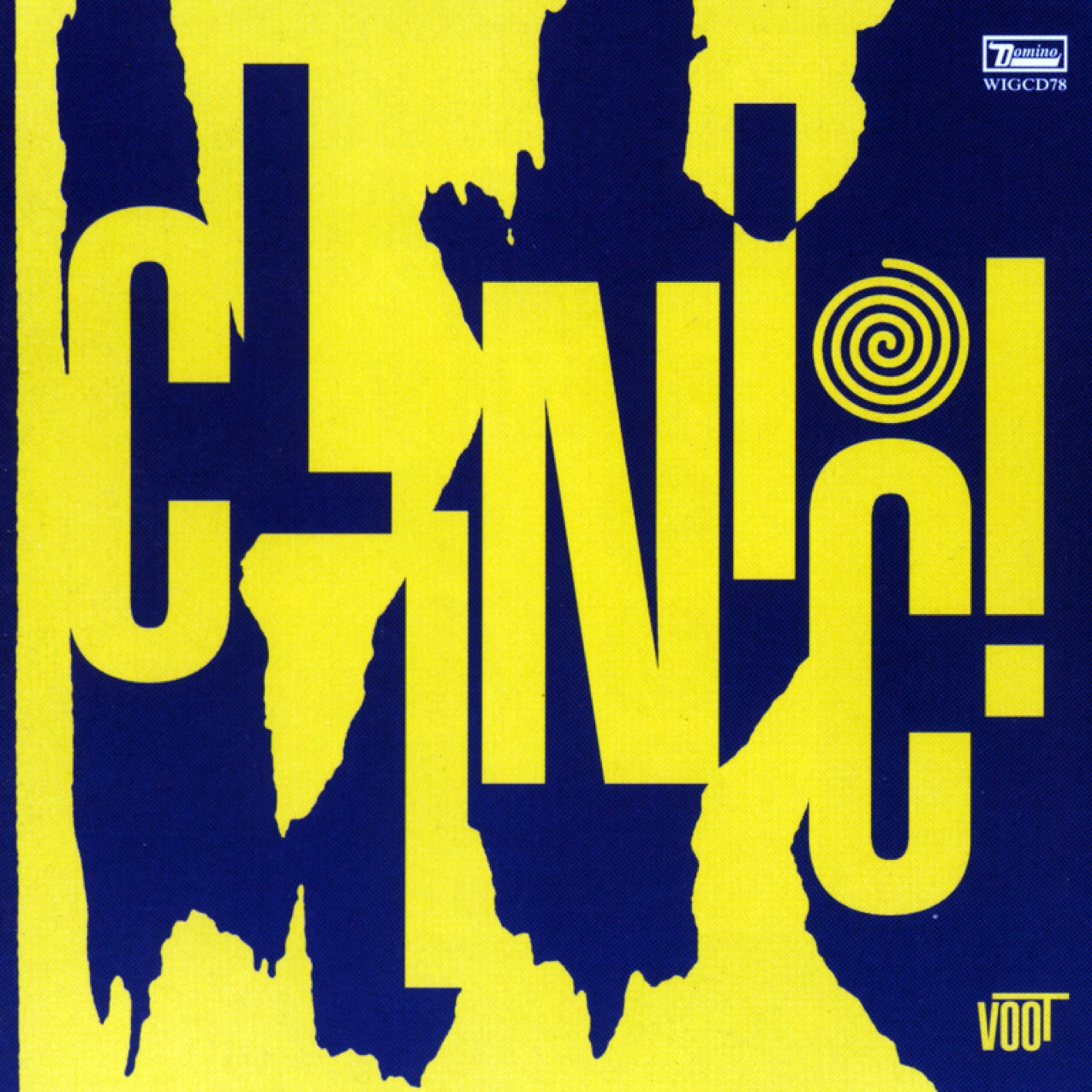

Clinic were capable of even more brazen grabs than the Britpoppers were, they just lunged for less-obvious goods. Exhibit A: the Internal Wrangler cover art, a nearly direct lift from the sleeve of Ornette Coleman’s 1962 album Ornette! They didn’t even alter the color scheme much. This was before everyone had instant access to image searches, so if you weren’t already familiar with jazz from the early '60s you probably didn’t spot the connection. The same goes for another possible reference: The song titles on Ornette! are all initials, and Internal Wrangler seems to nod at that with a pair of tracks, "C.Q." and "T.K."

Artwork in the minimal CD liner notes of Internal Wrangler plays up the jazz connection. One panel presents a murky black-on-blue collage with the heading "Jazz Funeral," implying that herein lies both a mourning of death and a celebration of life. It also ties into the band’s pivotal 1999 single, "The Second Line," its name inspired by New Orleans' second line parades, a spinoff of the jazz funerals the city is famous for. (The opposite panel offers an even more obscure clue: the cover of a 1964 book called Games People Play by Eric Berne, with the author credit replaced by the title of an Internal Wrangler song, "DJ Shangri-La.")

[videoembed size="full_width" alignment="center"][/videoembed]

Among the many faces featured in the miniature "Jazz Funeral" mural are not only the obvious touchstones, but also the Residents, Tim Buckley, and other improvisers of different stripes. Clinic's own songs were often taut and to-the-point compared to the work of those pictured here, but there is an avant-garde element of loosely controlled chaos to Internal Wrangler. A few of its songs barely crack the minute mark, and the whole thing blows by in little more than half an hour. The thirteenth track is left empty with just a few seconds of silence.

"The album's really varied, but I suppose our grand unifying theory is that you've got to keep things concise, don't let ideas get stale," Blackburn told Melody Maker in October of 2000. "So many bands now just seem so pleased with the one idea they have, they just flog it to death and it gives them a good excuse to be totally indulgent musicians." Clinic had a developed ideology out of the gate, which could be because, as some notable bands do, they already had a previous life as a less-notable band. Blackburn, drummer Carl Turney, guitarist Jonathan Hartley, and bassist Brian Campbell spent the middle of the '90s as a unit called Pure Morning that released a string of singles and a lone album, Two Inch Helium Buddha, which came out on Radar Records in 1996.

Only a year after Two Inch Helium Buddha, Pure Morning had been dissolved and its members reconvened as Clinic. The new name didn’t presage a total creative about-face, but the Pavement-isms of Pure Morning had gone careening into the proto-punk underground of the '60s and '70s. Blackburn's voice now had a more highly strung edge. Instead of Radar, which went kaput in '98 anyway, Clinic’s first releases came out on their own Aladdin's Cave Of Golf label.

Those early singles -- which Domino Records subsequently compiled onto one release when Clinic signed to the label in '99 -- show the band taking their music both more and less seriously than they did in Pure Morning. "I.P.C. Subeditors Dictate Our Youth" was an abstract jab at the former British publishing giant IPC Magazines Ltd, which owned a number of the big trendsetting pop publications. Its B-side, "Porno," featured a wrinkle of noise toward the end that was an actual recording error which they decided not to iron out. "There’s a certain spontaneous nature to the music, but there is also a certain plan," explained Turney to the music website Neumu in 2001. "Anything that can create an impression, or stands out to the listener, I think is a good thing."

Every track on Internal Wrangler has something about it that stands out, that leaves an impression on the listener. "Voodoo Wop" is an opening incantation of whoops and buzzing flies over drum-circle bongos and seashore vibes. "The Return of Evil Bill" reimagines their earlier instrumental “Evil Bill” as a mangled Merseyside rockabilly single about the titular character, "With his funny walk/ And known to kill." The title track pushes Pink Floyd’s "Lucifer Sam" onto the set of a Spaghetti Western and starts firing shots at the ground under its feet. Not only does "Internal Wrangler" kick off with the same beat as the Shangri-Las' "Leader Of The Pack," the very next track is called "DJ Shangri-La."

[videoembed size="full_width" alignment="center"][/videoembed]

The way that Clinic repurpose the trumpet hook from Johnny Cash’s "Ring Of Fire" on "T.K." is a feat, in that it's so up-front over the song's rumbling-floor-tom funk that you almost don’t see it. Amidst the album’s splice-and-dice of the Velvet Underground, the Modern Lovers, Can and other keystones in the lingua franca of indie rock, these other echoes can slip by unnoticed. Is that the knight helmet drum solo from Monty Python's "Camelot Song" in the middle of "C.Q."? Isn't there already a pretty famous tune called "Earth Angel"?

There was so much happening in such a tight space that it wasn’t always clear what was really going on. Spin heard DJ Shadow’s "Organ Donor" in "DJ Shangri-La," and in a sense that kind of crate-digging isn’t so different from the way Internal Wrangler operates. In the magazine's 9/10 review, "The Second Line" was also compared to Liquid Liquid’s "Cavern" as if "played by people who couldn’t remember how it went and forgot what they were trying to copy by the time it was over, and so have you." The similarity to "Cavern" is debatable, but this allusion speaks to a Rorschach effect that comes with record-collector rock. Whatever the artist’s intent, at some point listeners will start to see their own favorite LPs in the inkblots.

The ideas in "The Second Line" don’t feel secondhand, and whatever inspirations lay behind it come second to the fact that it’s an inspired two-and-a-half-minute jam -- so much so that Blackburn’s lyrics are practically spoken in tongues. Don't even bother to look them up. The song builds on a core of throbbing bass and wired groove, spinning off shards of coiling guitar and choked doo wop, until the gibberish-chant euphoria rises to a release of scorched melodica. It was a jolt back then, and it still sounds spastically inventive.

That goes for Internal Wrangler as a whole. Repetition and unpredictability coexist in unstable harmony. "2/4" is bluntly mechanical and maniacal. "2nd Foot Stomp" scrapes the glitter off '70s glam rock but doesn’t harm the giddy disorientation at its heart. The few calm moments are also the most sinister. The cooing anti-ballad "Distortions" offers some of the only comprehensible lyrics on the record, and they are often off-putting: "I've pictured you in coffins/ My baby in a coffin/ But I love it when you blink your eyes/ I want to know my body/ I want this out, not in me/ I want no other leakage/ I want to know no secrets yet."

[videoembed size="full_width" alignment="center"][/videoembed]

Internal Wrangler felt like the work of a band on a mission. The uniformity and anonymity of Clinic’s presentation only heightened this impression. Those matching masks and outfits never came off when the band were on stage or on camera, and while the liner notes name the producer, engineers, and assistants, the band members themselves are not listed. That mission, though, was similarly veiled. Were they out to save rock's future by blowing up its past? Were they just skipping jagged stones across the placid surface of the Britrock mainstream? (Was it part of the plan to bring the ambience of the Liverpool waterfront to the world, mixing seagulls and waves into "Voodoo Wop," "DJ Shangri-La," and "Earth Angel"?)

Clinic's next steps were nearly as unpredictable, but in a different way. Walking With Thee followed Internal Wrangler in 2002 and found a steadier sonic footing. Its songs practically flowed into one another, and only "Pet Eunuch" really brought back the garage rampage. Their aesthetic was more or less intact, but the abrasiveness had a new coat of varnish over it. The album’s most contrarian move was to circumvent a chorus in the title track by shouting an outright denial to provide one: "No!" No chorus for you.

"Right from the off, we decided that we didn't have anything in common with contemporary bands...and I think that's ongoing," Blackburn said in a 2002 interview. "It [seems] that in Britain each year, another conservative band is always being pushed as being the saviours of something and that gave us the freedom to do whatever we felt like." Walking With Thee ended up losing the 2003 Grammy for Best Alternative Music Album to one of those saviors, Coldplay, and their A Rush Of Blood To The Head, but the fact that it was even in that mix with Beck and Elvis Costello was the weirdest part about it. Clinic hadn’t made any real concessions to get invited to that party, but had come to a more approachable place on their own terms.

Walking With Thee set the tone for the band’s next decade, a future which had looked less certain through the cracked, sweat-fogged lenses of Internal Wrangler. Compared to their capricious debut, Clinic came to have an almost maddening consistency. They released a new album every two years like clockwork, with each one offering variations on their now-set foundational elements, some of which went all the way back to "Monkey On Your Back," "Cement Mixer," and their other earliest songs. Tacked on to the end of CMJ New Music Monthly’s review of Walking With Thee was the oddly prophetic assessment that, "While Clinic’s far from outworn their welcome yet, delivering a third record shaped from the same cookie-cutter could certainly dull the outpouring of love they've gotten Stateside so far." Throwing the term "cookie cutter" at Internal Wrangler two years before would have been unthinkable.

Clinic have in a way reverted to more mysterious ways this past decade. In late 2012 they released their strongest album in some time, Free Reign. It was followed months later by Free Reign II, a remix album by Daniel Lopatin of Oneohtrix Point Never, who had worked on the original. Then came six long years of relative silence, broken by Wheeltappers And Shunters in 2019. Blackburn had long ago expressed discomfort with the idea of Clinic doing anything directly political, but Wheeltappers And Shunters took aim at some of the less savory entrenched aspects of Britain's character in the Brexit era. On the record, the band sounds purposeful and playful -- not exactly like the Clinic of Internal Wrangler, but that would defeat the point. As the saying goes, those who cannot remember the past are condemned to repeat it.