We now know what Janelle Monáe would have done differently. Her third album, 2018's Dirty Computer, would have actually been her first, since she actually came up with its overarching concept 10 years ago. But she'd have to be upfront about her personal journey, as she was last year, when she came out as pansexual. She'd have to untangle her conflicted relationship with the American Dream, as she does throughout Dirty Computer. In order to level with listeners in the present day, she'd need to be more open, more human. "I needed to make sure I had the confidence not to self-edit," she said to Fault magazine. And so now we regard her actual debut, The ArchAndroid, as Monáe running away from the present, from who she is.

However, 10 years ago today, the future of music was Cindi Mayweather, the titular ArchAndroid. It was building a music career as a sci-fi franchise. (Subtitled Suites II & III, The ArchAndroid was technically a sequel, following a 2007 EP, Metropolis Suite I: The Chase Suite, that had Diddy courting her for Bad Boy Records.) It was citing Do Androids Dream Of Electric Sheep? but casting herself as the lead instead of Harrison Ford. The ArchAndroid could be read as escapism, sure. But Monáe, an androgynous black woman, was still making an ambitious case for representation before she'd be at the center of diversity conversations a decade later.

As R. Kelly incarnates like Trey Songz made contemporary R&B brasher and flashier, Monáe performed acoustic "dorm lounge tours" around Atlanta University Center, as if inspired by The Miseducation Of Lauryn Hill. She appeared twice on the soundtrack for Idlewild, OutKast's 2006, Prohibition-era film of the same name. Critics often compared Monáe as a live performer to James Brown, whose music she refused to file under a single genre. "I mean, James Brown was in soul, but to me he represented punk, rock and roll, he helped influence the Rolling Stones -- he was all of that,” she said to The Quietus. Before Chuck Lightning became creative director of Wondaland Arts Society, he introduced Monáe to pioneering sci-fi film Metropolis, which inspired her alter ego's retro-futurist backdrop.

In The ArchAndroid, Monáe continued to stage a protest against the very industry she faced. "As a black woman in today's music industry, it's important that people understand that we're not all monolithic," shesaid to Pitchfork. "It's time that we just break past this notion that if you're an African American female that you have to stick to one genre. One boring genre, at that." Just as before, Monáe made her case by taking inspiration from the past.

[videoembed size="full_width" alignment="center"]https://youtube.com/watch?v=pwnefUaKCbc[/videoembed]

Throughout, Monáe channels black artists who've broken music conventions before her. Think Janet Jackson's Rhythm Nation 1819, with how The ArchAndroid begins by staging a dance revolution ("Dance Or Die" featuring Saul Williams, "Faster"). Think Stevie Wonder, with Monáe's genre foraging (compare "Tightrope," featuring Big Boi, to "Make The Bus," featuring Of Montreal) and The ArchAndroid's demand to be taken seriously as a full-length statement. Even the refined air and piercing clarity in Monáe's voice ("Say You'll Go") recalls Nat King Cole, who was accused of selling out before he transitioned from a jazz pianist to one of the most celebrated pop vocalists of all time. Referencing this people's history of black music is The ArchAndroid's greatest feat in time-traveling.

As a sci-fi hero, though, Monáe's vision for the future was unclear. This had been true since before The ArchAndroid. In "Many Moons," the Grammy-winning Suite I single, Monáe raps about who she wants to represent. One moment she sounds like she could be speaking for herself: "Outcast, weirdo, stepchild, freak show/ Black girl, bad hair / Broad nose, cold stare." Then the laundry list of causes -- "Spoiled milk, stale bread/ Welfare, bubonic plague" -- gets even longer, diminishing her rallying cry. In The ArchAndroid, Cindi, the android, falls in love with Sir Greendown, a human. We could surmise that this would typically end with a happily ever after, if such relationships weren't forbidden. "The droid control will take your soul and rate it," Monáe raps on "Neon Valley Street." But the best works of science fiction would make those consequences feel more tangible, even if they do speak of a distant future.

In the arts, the specific is universal. As of late, Monáe has only stopped short of discussing her dating life. It makes sense that she now feels conflicted about Cindi Mayweather. In 2007, when she was 21, Monáe figured that "you can parallel the other in the android to being a black woman right now, to being a part of the LGBTQ community. What it feels like to be called a n---- by your oppressor." Now she says that by assuming this alter ego, she "didn't have to talk about the Janelle Monáe who was in therapy." We now talk about Cindi Mayweather as if she was only means for Monae to hide her "true" self.

[videoembed size="full_width" alignment="center"]https://youtube.com/watch?v=lqmORiHNtN4[/videoembed]

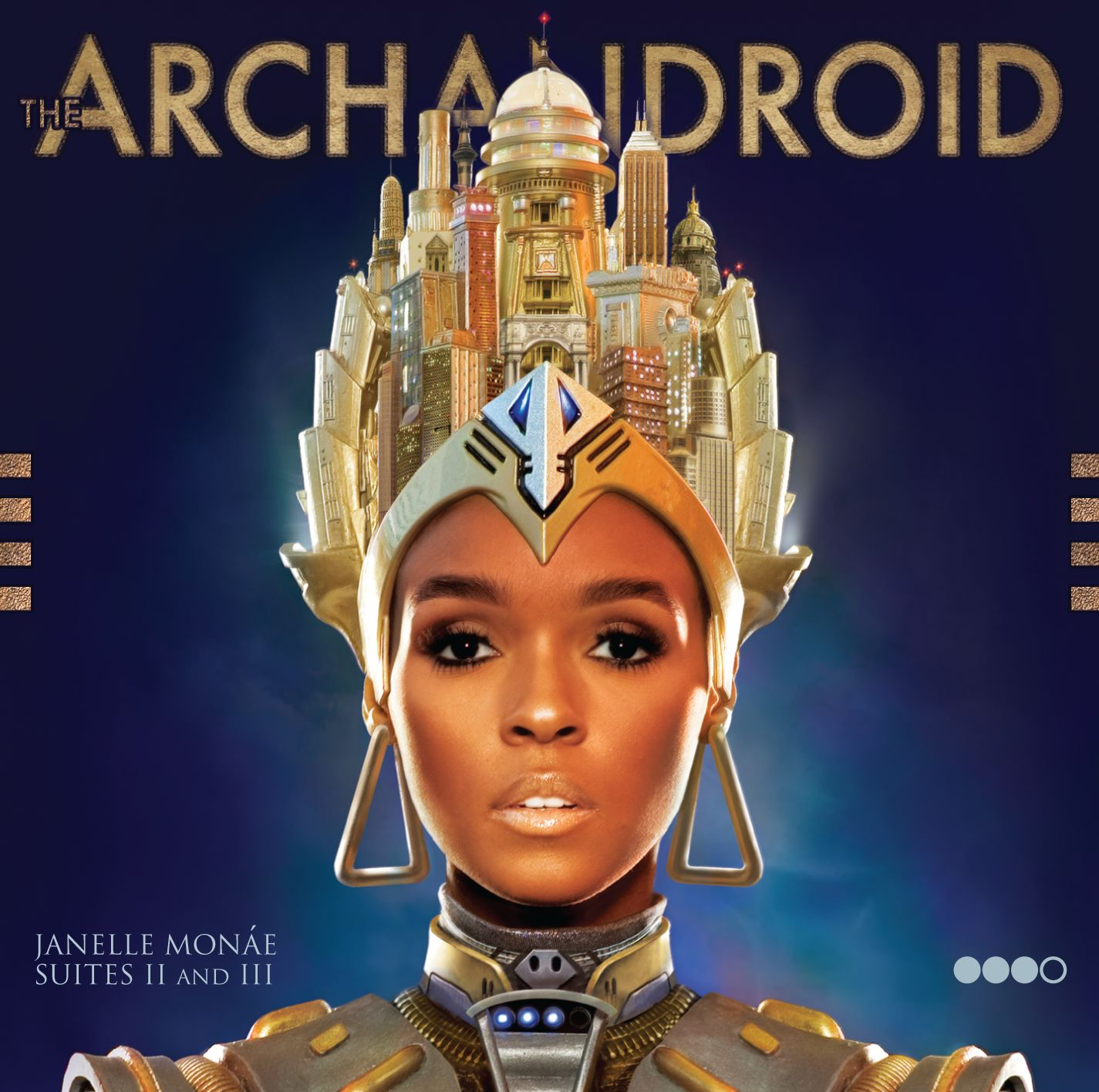

But surely Monáe understands how powerful visibility can still be. What has endured over the past decade is the very image on The ArchAndroid's cover art -- this young black woman re-imagined as Metropolis' activist hero Maria. In season 4 of RuPaul's Drag Race, which aired in 2012, contestant Milan defended her decision to dress as Monáe for the runway, despite how all the judges could see was "boy." (RuPaul himself didn't acknowledge what was happening until three years later: "I think season 4 is the first time we introduced gender fuck drag.") Last year, Monáe inspired Queer Eye's makeover of Jess Guilbeaux, the first lesbian to appear on the show. After the show, Guilbeaux made her drag debut lip-syncing to Monáe's "Yoga."

In Dirty Computer's accompanying "emotion picture," New Dawn enforcers plan to wipe away the memories of law-breaking citizen Jane 57821. (Jane shares the same registration number as The ArchAndroid's Cindi Mayweather, though the short film doesn't make that connection explicit.) Those Dirty Computer flashbacks recall the music video revolution, a time when many of Monáe's heroes -- Janet, Prince, David Bowie -- thrived. Monáe still bucks the status quo by inserting herself into familiar contexts to make them feel new again.

This year Monáe replaces Julia Roberts in the Amazon Originals series Homecoming, searching for clues about her identity in a world run by a nefarious corporation. She also scored her first leading motion picture role in Antebellum, a mind-bending, horror take on the slavery films that have historically been awards show bait. (Lionsgate pushed its North American release from April to August, as COVID-19 hit stateside.) Monáe's promising acting career, along with what she already accomplished with Moonlight and Hidden Figures, continues to make a case for diversity in Hollywood. But 10 years ago, before all that, The ArchAndroid arrived as a proof of concept.