In The Number Ones, I'm reviewing every single #1 single in the history of the Billboard Hot 100, starting with the chart's beginning, in 1958, and working my way up into the present.

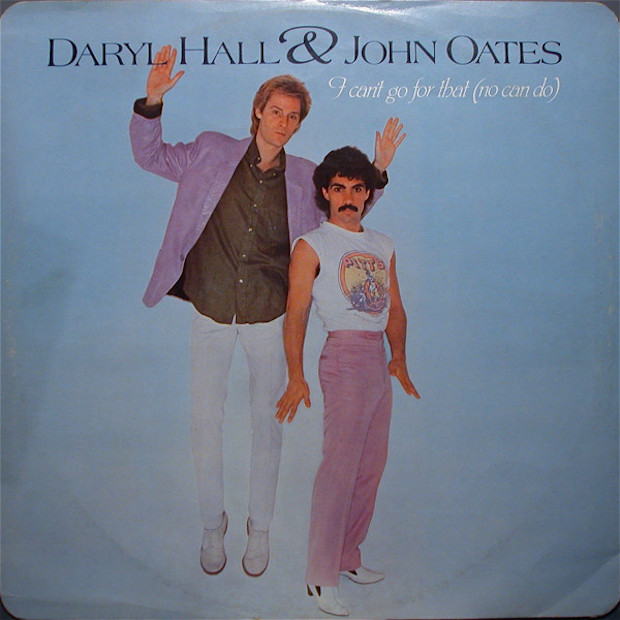

Daryl Hall & John Oates - "I Can't Go For That (No Can Do)"

HIT #1: January 30, 1982

STAYED AT #1: 1 week

It's late one night during the Private Eyes sessions at New York's Electric Lady studios. Just about everyone has gone home for the night. But Daryl Hall is still there, messing around with an early drum machine. He hits one of the preset buttons on the Roland CompuRhythm, a doohickey that had come out a few years earlier, and he likes the stark beat that comes out of it. Without thinking much about it, Hall starts playing a gentle, insistent bassline on his Korg keyboard. John Oates is still in the studio, so Hall yells for Oates to plug in his guitar and play a particular riff. Hall also yells for the sound engineer, the only other guy still in the studio, to hit record.

After they get all that down, Hall and Oates work on that guitar riff a little more. The next day, Hall gets together with his girlfriend Sara Allen, who'd also helped write the duo's previous #1 hit "Private Eyes," to write some lyrics. With those new lyrics, the song sounds like a relationship track -- a guy who's at a power-imbalance disadvantage but who doesn't want to be pushed around anymore. But Hall says it's really about the music business, about refusing to jump through all the hoops in front of him: "I'll do almost anything that you want me to. But I can't go for that. No can do."

Talking to The Guardian a couple of years ago, Hall said "I felt very manipulated at the time, by management and the record business. Like a pawn." It makes sense. Hall and Oates had been making records together for nearly a decade, and Private Eyes was their 10th album. They'd had good times, and they'd had dry stretches. They'd bounced from label to label, and they'd made compromises that they'd later regretted. They'd found their greatest success only when they'd seized artistic control of their own records.

But in the early '80s, Daryl Hall was basically pushing the music business around, doing whatever he wanted. He couldn't lose. It's possible that Hall and Oates were the biggest act in the world during the pre-Thriller moment. Hall and Oates had gone to #1 with "Private Eyes" in the fall of 1981, and then Olivia Newton-John's pop juggernaut "Physical" had knocked them out of the top spot. But as soon as "Physical" ended its run, Hall and Oates were right back on top with "I Can't Go For That (No Can Do)." With "I Can't Go For That," Hall and Oates also became the rare white act to hit #1 on the Billboard R&B chart. (In the biography Dangerous Dreams, Nick Tosches writes that Hall, upon learning of this achievement, called himself "the head soul brother in the US." I can't go for that.)

The cool thing about "I Can't Go For That" is that it doesn't sound like a song of music-business frustration. It doesn't even sound like romantic frustration. It simply sounds like a sleek and airless groove, a beat for Hall to ride. Most of Hall and Oates' band didn't even play on "I Can't Go For That"; the final product just had skeletal bass and guitar and some artfully deployed Charles DeChant sax-tootling behind Hall's synths and that drum-machine groove. The song itself is sparse in the best way. It glides and slides and insinuates.

"I Can't Go For That" is a song of tiny touches and flourishes, and all of those tiny touches work: The reverb on the drum machine, the sly itchiness of the guitar, the tingly keyboard wobbles. Hall's voice is slick and controlled. He shimmies up and down the track. He sings little runs that let us know that he could oversing, but he also makes sure that he never actually does it. With the backing vocals come in on the chorus, they're dreamworld doo-wop. Hall sounds like he's dancing with them. Everything has just the right level of echo.

There's nothing monumental about "I Can't Go For That." It's a song built from coiled restraint -- all tension, no release. Later on, Michael Jackson would use a slightly-adapted version of Hall's genuinely funky bassline for another song that'll appear in this column, and he'd increase the tension to great effect. (Hall claims that Jackson freely admitted that he'd stolen the "I Can't Go For That" groove to him. Hall wasn't bothered.)

But "I Can't Go For That" isn't a rough draft. It's a pretty great piece of swaggering minimalism in its own right. Even the stick-in-your-head chorus, something that often drives me nuts about Hall and Oates' songs, absolutely works. For Hall and Oates, everything was clicking. This column isn't done with them, yet.

GRADE: 8/10

BONUS BEATS: De La Soul built their great 1989 single "Say No Go" from an "I Can't Go For That (No Can Do)" sample. Here's the video:

https://youtube.com/watch?v=WwV2MWZ9U0o

(De La Soul have never made a top-10 hit. Their highest-charting single, 1989's "Me Myself And I," peaked at #34.)

BONUS BONUS BEATS: Above The Law sampled "I Can't Go For That (No Can Do)" on their 1993 single "V.S.O.P." Here's the video:

BONUS BONUS BONUS BEATS: Trigger Tha Gambler and Smoothe Da Hustler interpolated "I Can't Go For That (No Can Do)" on "My Crew Can't Go For That," their contribution to 1996's Nutty Professor soundtrack. Here's the video:

BONUS BONUS BONUS BONUS BEATS: Here's MF DOOM chopping up an "I Can't Go For That (No Can Do)" sample on his 2003 King Geedorah skit "Take Me To Your Leader":

BONUS BONUS BONUS BONUS BONUS BEATS: The xx used a ghostly sample of "I Can't Go For That (No Can Do)" on their 2016 single "On Hold." Here's the video: