"Tower Records told me to shove this record up my ass. Do you know how it feels to be told to shove a record up your ass?" That's Steve Berman, real-life circa-2000 president of sales at Interscope, talking to Eminem on "Steve Berman," one of the skits from The Marshall Mathers LP. In that skit, Eminem's visiting his label's corporate offices, and Berman is telling him everything that's wrong with the new album that he's just delivered. Berman is heated. "Do you know why Dre's record was so successful?," Berman asks. "He's rapping about big-screen TVs, blunts, 40s, and bitches. You're rapping about homosexuals and Vicodin. I can't sell this shit!" (I don't remember any lyrics about big-screen TVs or 40s on Dre's 2001, but nevermind.)

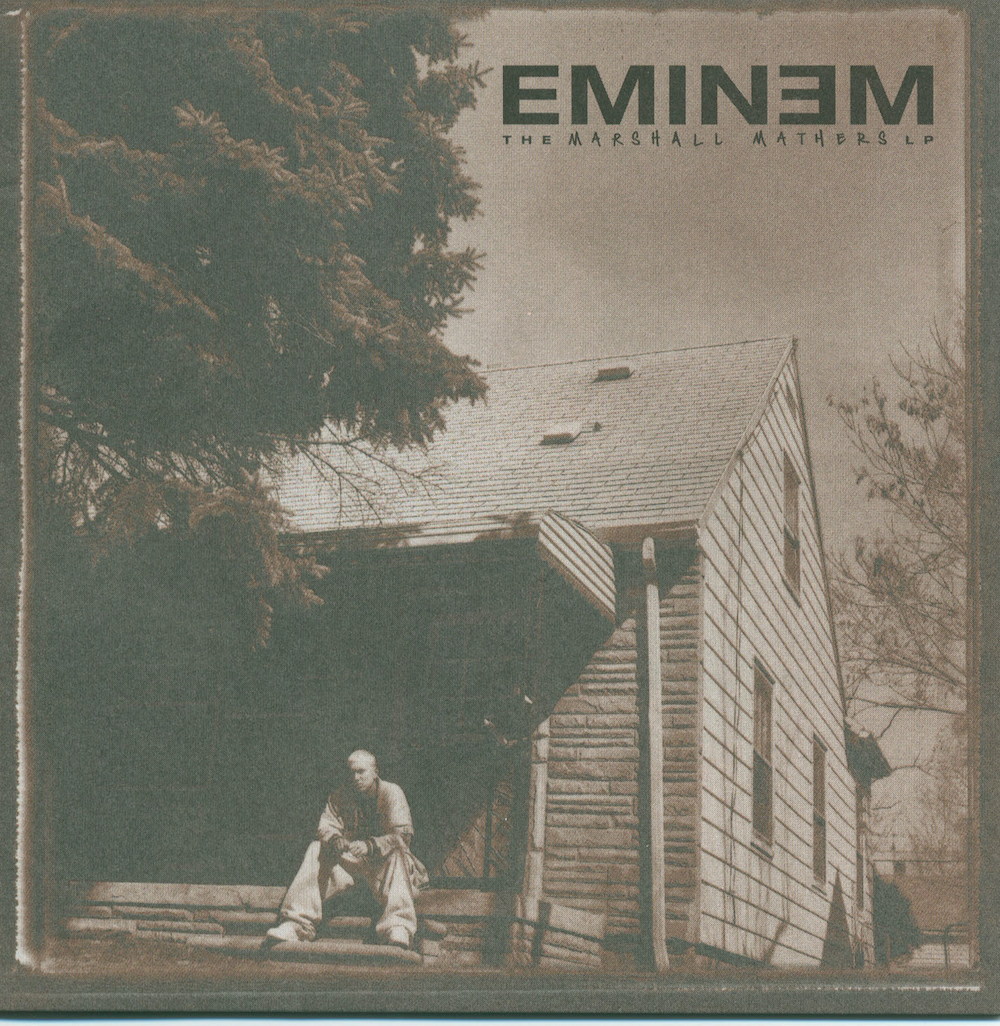

Steve Berman, of course, did sell this shit. The Marshall Mathers LP is 77 straight minutes of death threats, virulent homophobia, ain't-I-a-stinker edgelord gags, language-drunk wordplay, and psycho-sexual rage-venting. To listen to it is to feel bad, even when you're thrilled. The Marshall Mathers LP sold nearly 2 million copies in its first week -- more than twice as much as the Marshall Mathers LP guest and previous Dr. Dre protege Snoop Dogg, rap's previous first-week sales champ, had managed with 1993's Doggystyle. Before long, The Marshall Mathers LP had become the best-selling rap album of all time, a title that it still holds today.

When I first heard that line about Tower Records, it didn't quite take. I was sitting on a bus-stop bench somewhere in Lower Manhattan, head spinning, trying to process everything I'd just heard. "Steve Berman" had showed up on The Marshall Mathers LP a few tracks after "Stan," Eminem's breathless and riveting narrative about an obsessed and ultimately murderous fan. This was on May 23, 2000 -- 20 years ago tomorrow. The Marshall Mathers LP had come out that day. I had the day off work, so I took the subway to the Tower Records in Soho and bought the tape. I don't remember what else I'd planned to do that day, but once I heard "Stan," all that was over. I couldn't even walk around with the album. I had to sit with this thing on my Walkman. I had to digest.

When I'd walked into Tower that morning, the store had a giant display of nothing but The Marshall Mathers LP -- hundreds of copies of it. Tower Records had definitely not told Steve Berman to shove the record up his ass. They'd probably sent him a bottle of champagne. This was the height of the CD era, the final boom time before internet piracy would plunge the record business into the dark ages, and everyone could tell that The Marshall Mathers LP was an immediate blockbuster. But a huge part of the album's success was Eminem's eagerness to play the underdog victim. "Radio won't even play my jam," Eminem bitched, at a moment when radio played little else. "I'm not Mr. *NSYNC, I'm not what your friends think," Em insisted, when he was competing with fellow hair-bleach and bouncy-harpsichord enthusiasts *NSYNC for TRL-driven sales dominance.

On The Marshall Mathers LP, Eminem talks about himself as if he's public enemy number one, as if he's the most hated person in the history of mainstream America. This is an act. He wasn't that -- not yet, anyway. A little more than a year earlier, The Slim Shady LP had sold well and established Em as a shock-rap star. He'd been on arena tours -- as opener, not headliner -- and he'd rankled public-taste watchdogs like Billboard editor Timothy White. But his success wasn't a public crisis yet. Still, Eminem spends The Marshall Mathers LP speaking about himself as an inescapable pariah -- the despised colossus who stands astride the world. As soon as the album came out, that's exactly what he became.

On The Marshall Mathers LP, Eminem's great superpower is an ability to magnify every perceived slight to absurd degrees. In an anodyne MTV segment, Christina Aguilera had mentioned that Em had married Kim Mathers, the woman who he'd rapped about murdering on "'97 Bonnie & Clyde." This was a tiny on-air moment, not some grand campaign that Aguilera was waging. But at the time, it wasn't public knowledge that Em had married Kim, so Em was furious. On "The Real Slim Shady," the ridiculously catchy first single from The Marshall Mathers LP, Em goes nuclear against Aguilera, imagining himself at the VMAs, sitting "next to Carson Daly and Fred Durst, and hear them argue over who she gave head to first." It's a wild, dizzy, indefensible overreaction -- one of many.

Eminem has so many enemies on The Marshall Mathers LP: Parents, teachers, gay people, journalists, boy bands, girl groups, Insane Clowns, his own fans, his mother, his wife, himself. A couple of years before he made the album, Em had been a white-trash no-hoper in Detroit, a grown kid with a failed rap career and a daughter he couldn't afford to raise. Em had transcended his origins through sheer profane ingenuity and force of personality and a lucky connection to Dr. Dre, and he'd suddenly become a public figure. But he was still miserable. His wife was cheating on him, and he was getting into fights over it, getting arrested. His mother was suing him for rapping about her. He was going through it, and he was telling jokes about going through it: "Tell me, what the hell is a fella to do?/ For every million I make, another relative sues."

Trolling didn't exist as a verb in 2000, but that's what Eminem does all through The Marshall Mathers LP. He'd noticed that his homophobia on The Real Slim Shady had made people uncomfortable, so he doubled down on it, admitting later that he'd done it just to piss people off. Pissing people off had become his religion. This was a cruder time in American public history, when you could become a free-speech crusader just by saying fucked-up shit and daring uptight old people to react. (Lynne Cheney, another Eminem adversary, took the bait, complaining about his lyrics on the floor of Congress.) Em caught the same wave that the South Park guys did, riding shock-value infamy to towering mainstream fame. On the album, Em plays the villain -- "I was put here to annoy the world, and destroy your little four-year-old boy or girl" -- because he knows that this will make him a hero.

As irresponsible as Em gets on The Marshall Mathers LP, though, he also vents a whole lot of anxiety about his own success and what that might mean. Sometimes, he's outwardly offensive, as on all the moments where he raps about the Columbine massacre, "a whole school of bullies shot up all at one time." Sometimes, he's defensive, insisting that he's not society's problem: "What about the makeup that you allow your 12-year-old daughter to wear?" Sometimes, he's self-conscious, fretting about being "in rotation on rock 'n' roll stations" just because of his race. And sometimes he's piercingly, fearfully vulnerable. That's the power of "Stan," a nearly-seven-minute Hitchcockian horror story about the kid who takes all of Eminem's jokes the worst possible way.

"Stan" is a fascinating relic now -- a genuinely cutting and absorbing story-song that entered the lexicon, changed the dictionary, and gave toxic fandom a name. Producer Mark The 45 King sampled a ballad from the relatively unknown British trip-hop siren Dido and briefly turned her into a star on American adult contemporary radio. (This was less than two years after the 45 King had sampled Annie for Jay-Z's "Hard Knock Life (Ghetto Anthem)." Has a not-that-famous producer ever had such a culturally impactful one-two punch?)

My colleague Chris DeVille just wrote a whole piece about the legacy of "Stan," but the song also served a function in the moment. At the 2001 Grammys, the same night that he famously lost Album Of The Year to Steely Dan, Eminem performed "Stan" with Elton John, making a feeble attempt to defuse all the homophobia accusations. The song choice was auspicious. "Stan" is the moment where subtext becomes text, where Eminem makes his vulnerability plain. Em wasn't just a spitball-shooting outrage magnet. He was also a smart and incisive storyteller. You couldn't hear "Stan" and believe otherwise.

If you're listening closely enough, that vulnerability is all over The Marshall Mathers LP. Em imagines himself in a nursing home at 30, or staying home with a 40 at 40, babysitting his daughter's kids while she's out getting plastered. He gives voice to his own worst impulses -- to the worst impulses that anyone could have. The previous album's "'97 Bonnie & Clyde," where Em babbled lovingly to his daughter while disposing of her mother's body, was bad enough. The Marshall Mathers LP gave us the harrowing prequel "Kim" -- six minutes of crying and screaming and, finally, murdering: "You were supposed to love me! Now bleed, bitch, bleed!"

I hated "Kim." It stressed me out, and made me sad, and exhausted me. So I avoided the song. I had the album on cassette, so I couldn't just skip the song. Most of the time, I just fast-forwarded the tape to the end of the second side, sacrificing "Under The Influence" and "Criminal" so that I wouldn't have to listen to "Kim" again. You couldn't endure "Kim" and think that Eminem was cool, that he was someone worth emulating. He sounds pathetic, unhinged, his own worst-nightmare version of himself. But even on "Kim," Em imagines himself as the victim, immune to whatever harm he may be inflicting on the rest of the world. It's a perennial Eminem problem. As much as he fumes about bullies, he can't process the idea that he might be one.

"Kim" plays out like a movie -- dialog, sound effects, Em doing his own wife's death-scream voice. "Stan" works the same way, with pencil scratches and car-in-river splashes giving physical dimension to the stories that he's telling. The level of craft on The Marshall Mathers LP remains staggering. Where Dr. Dre only produced a few tracks on The Slim Shady LP, he and his proteges take over for much of Marshall Mathers, giving Em a tense, springy blockbuster-rap heft. And even when Em produces himself, as on the gothically pretty "The Way I Am," the music has scope.

In terms of pure rapping technique, The Marshall Mathers LP is almost peerless. On his more recent records, Eminem has turned rap virtuosity into an empty technical display. But on Marshall Mathers, Em shows urgency and personality even when he's speeding rings around his tracks. The album's maddening catchiness is almost a problem. Em raps in absurdist, transgressive nursery rhymes that remain permanently lodged in my brain decades later: "Skippity bebop, Christopher Reeve!" I have spent most of the time since 2000 working in the music media, and yet I can't see the word XXL without immediately hear Em's clowning echoing in my skull: "Maybe now your magazine won't have so much trouble to sell!"

The Eminem of 2000 was such a great rapper that he could make anything sound compelling -- Tom Green catchphrases, UFO cockpit-radio chatter, intra-MTV gossip. A lot of it was terrible. The "Ken Kaniff" skit, wherein the two members of Insane Clown Posse give loud and slobbery blowjobs to Em's menacing gay sketch-comedy character, is probably the most uncomfortable thing to have playing on your stereo when anyone else walks into your room. In decades of pornographic sex-noise rap-album skits, I don't think anyone's ever made anything worse. And yet I still kept listening. So many of us did. Apparently, there was a million of us just like Em, who cussed like Em, who just didn't give a fuck like Em.

Twenty years later, I look at The Marshall Mathers LP the same way I look at a right-wing revenge fantasy like Dirty Harry -- all this impeccable craft put in service of a self-pitying and repellant worldview. I love it, and I hate it. I admire Eminem's skills, and I empathize with him, but I also sneer at every aside about his own victimhood. If Tower Records really had told Steve Berman to shove the record up his ass, maybe society would be better off right now. But Tower sold it, and I bought it. Me and everyone else.