In The Number Ones, I'm reviewing every single #1 single in the history of the Billboard Hot 100, starting with the chart's beginning, in 1958, and working my way up into the present.

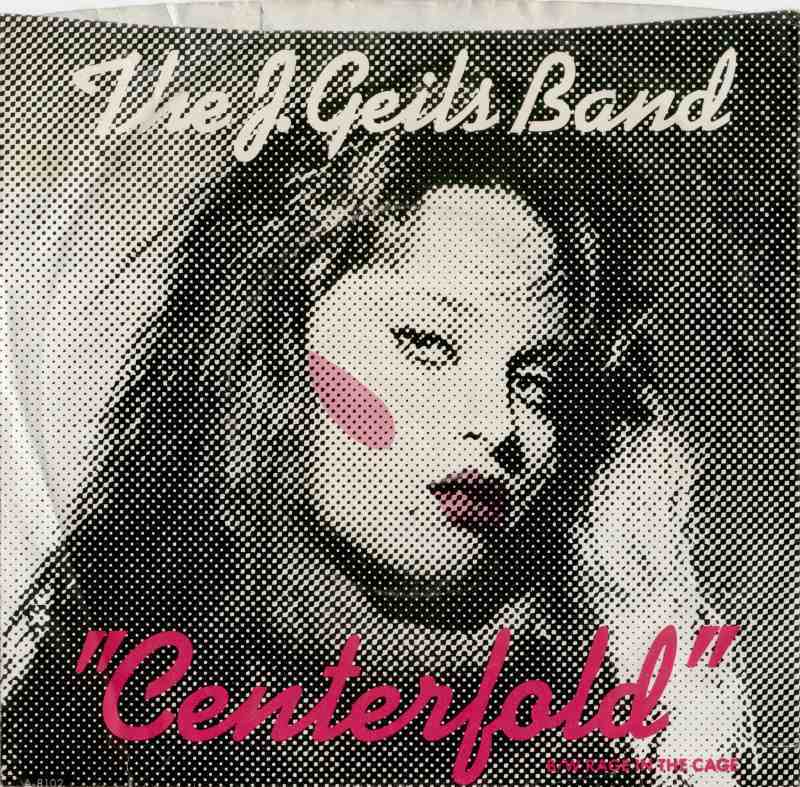

The J. Geils Band - "Centerfold"

HIT #1: February 6, 1982

STAYED AT #1: 6 weeks

The party band is a rich and noble tradition. The party band's story usually goes something like this: A bunch of college buddies get together to play fun, uptempo R&B covers at local frats and dive bars. If they're good enough, maybe they'll eventually hit the local club circuit. If they're really good, maybe they'll sign to a label, put out a couple of records, open for a bigger band on tour. Usually, that's the absolute ceiling. The party band isn't supposed to become a significant artistic or commercial force. If that's what they'd wanted to be, they would've stopped being a party band. But every once in a long while, you will find a party band that takes off while still remaining a party band. Every once in a long while, the party band wins.

By the beginning of the '80s, the J. Geils Band, perhaps America's ultimate party band, had been together for more than a decade. They'd recorded 10 albums. They'd developed a rep as one of the most purely fun live bands in America, a distinction that'd landed them spots opening for bigger stars like the Rolling Stones and Peter Frampton. They'd even scored a few minor hits. But they'd never been anything more than a party band -- at least not until they finally harnessed the twin forces of MTV and new wave, briefly becoming bona fide stars before splintering. Naturally, the song that pushed them over the top was a horny and conflicted na na na singalong about seeing a high-school crush naked in a porno mag.

John Geils, Jr. put together the first iteration of his band when he was at college in Worcester, Massachusetts in the late '60s. Originally, they were an acoustic blues trio -- Geils on guitar and Danny Klein on bass, along with a harmonica player who still calls himself Magic Dick. After a little while, they decided to go electric, bringing in drummer Stephen Bladd and a ringer of a frontman known as Peter Wolf.

Wolf -- real name Peter Blankenfield -- was a Bronx native who'd moved up to Boston for art school. (His freshman-year roommate was David Lynch. Wolf and Lynch have not had any detectable influence on each other's artistic lives.) Wolf had spent a little while fronting a Boston band called the Hallucinations, and he'd landed a job as the overnight DJ on the local rock station WBCN. On the radio, Wolf developed a persona as rambling, cartoonish, fast-talking hipster. Once Wolf joined the J. Geils Band, he found that his persona translated just fine to the stage. (That's the same arc that former Atlanta radio DJ Ludacris would follow decades later. He'll eventually end up in this column, too.)

The J. Geils Band signed to Atlantic in 1969 and released their debut album a year later, and then they spent the next decade grinding it out in the trenches. Their sound was good-times blues-rock, and Magic Dick's harmonica was usually their lead instrument. Most or all of the band members were Jewish, but they covered R&B songs and adapted R&B poses whenever they could. Wolf has claimed that this mindset -- "very black-oriented," he says -- is what led the band to turn down an offer to play Woodstock. They didn't like the idea of all that mud.

In the '70s, the J. Geils Band did just fine for themselves, touring and recording constantly and developing a big cult following, especially in party-rock hotbeds like Boston and Detroit. They banged out a steady stream of singles, most of which missed the Hot 100 entirely. A few of those singles made the lower reaches of the top 40. One, the 1974 rave-up "Must Of Got Lost," climbed all the way up to #12. ("Love Stinks," a 1980 anthem that eventually became a party-band standard, stalled out at #38.)

Early on, the J. Geils Band had a decent shot at becoming the American Stones. But then their fellow Boston club-scene act Aerosmith, a band that'll eventually end up in this column, came along and stole that title away from them. That must've been a tough thing for Peter Wolf, a charismatic and larger-than-life frontman in a band that wasn't named after him. (The whole J. Geils Band dynamic reminds me a lot of Van Halen, one more band that'll eventually be in this column.) Wolf was charismatic enough that he spent most of the '70s married to Faye Dunaway, but his band remained stuck on the B-list.

That changed with Freeze-Frame. Keyboardist Seth Justman, the J. Geils Band's producer and primary songwriter, says that the band never used synths before their 1981 album just because they couldn't afford them; they always owed too much to the labels. But on Freeze-Frame, the band latched onto the twitchy, bleepy aesthetic of new-wave rockers like the Cars and married it to the whole good-time sound that they'd already developed. (The Cars, like the J. Geils Band, came from the Boston club scene, and their single "Shake It Up" peaked at #4 while "Centerfold" was at #1. "Shake It Up" is a 9.) Freeze-Frame took the band away from blues-rock, and it made them stars.

"Centerfold," the J. Geils Band's one and only #1 hit, is a psychological tangle of a song. Wolf sings about a hopeless high-school crush on a "homeroom angel" who he'd always been too shy to approach. Then, years later, he finds that girl naked in a "girly magazine." He's upset about it: "My blood runs cold! My memory has just been sold!" The pristine and untouchable girl of his imagination just revealed herself as a sexual being, and he's not sure how to deal with it.

But Wolf's character gets horny, and he gets over it. He understands that he's not living some storybook romance: "It's OK! I understand! This ain't no Never Never Land." He imagines himself banging his homeroom angel in a motel room. And he finds some kind of inner peace with the whole dilemma: "A part of me has just been ripped/ The pages from my mind are stripped/ Oh no, I can't deny it/ Oh yeah, I guess I gotta buy it!" So he'd just been flipping through the magazine in a store? I definitely used to get yelled at for doing it as a kid. Maybe the gas-station clerk didn't want to bother 35-year-old Peter Wolf in the midst of his romantic reverie.

On paper, "Centerfold" might be a sad story -- a shy and lonely guy forced to confront the failures of his own imagination. In practice, though, "Centerfold" is a big, bouncy blast of a song. Wolf didn't write that song -- Justman is the sole songwriter -- so he's free to apply his whole cartoonish character to it. Wolf never sells the regret of those lyrics. Instead, he just savors the taste of the words in his mouth: "I wuz shakin' in my shoooes whenever she flashed those baby bluuues!" He sounds like a drunk doing a Bob Dylan impression. I love it.

The band doesn't take the situation too seriously, either. Instead, they build a supercharged synth-rock motor for it. These musicians are the kinds of guys who love to play big, blazing solos in their live shows, but they strip all that away for "Centerfold." Justman's juicy keyboard riff sounds like a mocking playground chant. Geils plays funky downstrokes and baritone counter-riffs. On the chorus, the whole band joins in, turning it into a rowdy gang singalong.

The guys in the band had been around long enough to understand fratty '60s garage rock, and they were canny enough to know that guitar-centric new wave was mostly just an updated version of that sound. All the little touches in the song -- the na na na refrain, the organ bleats, the false ending where someone counts it off before the band comes roaring back in -- are total crowd-pleasers. The band even does the thing where, at the end, it sounds like there's an actual party going on in the background -- literal party-rock.

The video helped, too, of course. Justman's brother Paul directed the clip, where a gaunt Wolf struts and shimmies through a classroom while cheerleaders dance around him. If the whole thing was the slightest bit serious -- if it wasn't a total live-action cartoon -- then this middle-aged high-school dance party might've been creepy. But who could object to that level of silliness? The whole spectacle has all the innocent giddiness of a '70s exploitation flick.

The band followed "Centerfold" up with "Freeze-Frame," another uptight and fired-up jam, and it peaked at #4. ("Freeze-Frame" is a 7.) But then Wolf, objecting to the band's synthy new wave direction, left the group, kicking off a solo career instead. Wolf had a decent little solo run, peaking at #12 with his 1984 debut single "Lights Out." The J. Geils Band tried to keep going without Wolf. They made one more album, 1984's You're Gettin' Even While I'm Gettin' Odd, with Seth Justman singing lead. It flopped, and the band broke up shortly thereafter. J. Geils went on to open up a sports car restoration shop in Massachusetts.

Wolf reunited with the J. Geils Band for a tour in 1999, and they kept getting back together for occasional shows over the next 18 years. The J. Geils Band is no more only because J. Geils himself is no more. Geils died of unspecified natural causes in 2017, when he was 71. His legacy is a party-rock legacy, and that's a legacy to be proud of.

GRADE: 9/10

BONUS BEATS: Here's Florida ska-punk hooligans Against All Authority covering "Centerfold" on their 1996 album Destroy What Destroys You: