Jed The Humanoid may not be one of science fiction's most iconic tragic figures, but his obscurity only emphasizes the sadness of his story. As Grandaddy's Jason Lytle tells it, the android first known as Jeddy 3 was assembled in the kitchen from whatever spare parts were lying around. "When we finished Jed we were so proud," Lytle sings in one of those quavering twee Neil Young voices that was so prevalent in indie rock at the turn of the millennium. Over a mournful chord progression drowning in synthesizers, Lytle goes on to explain that Jed could run or walk, sing or talk, and compile thoughts and solve lots of problems: "We learned so much from him." But as time moved on, Jed's inventors neglected him as they shifted their attention to flashier new technology, until one day he succumbed to alcoholism. "Jed had found booze and drank every drop," Lytle explains. "He fizzled and popped/ He rattled and knocked/ And finally he just stopped."

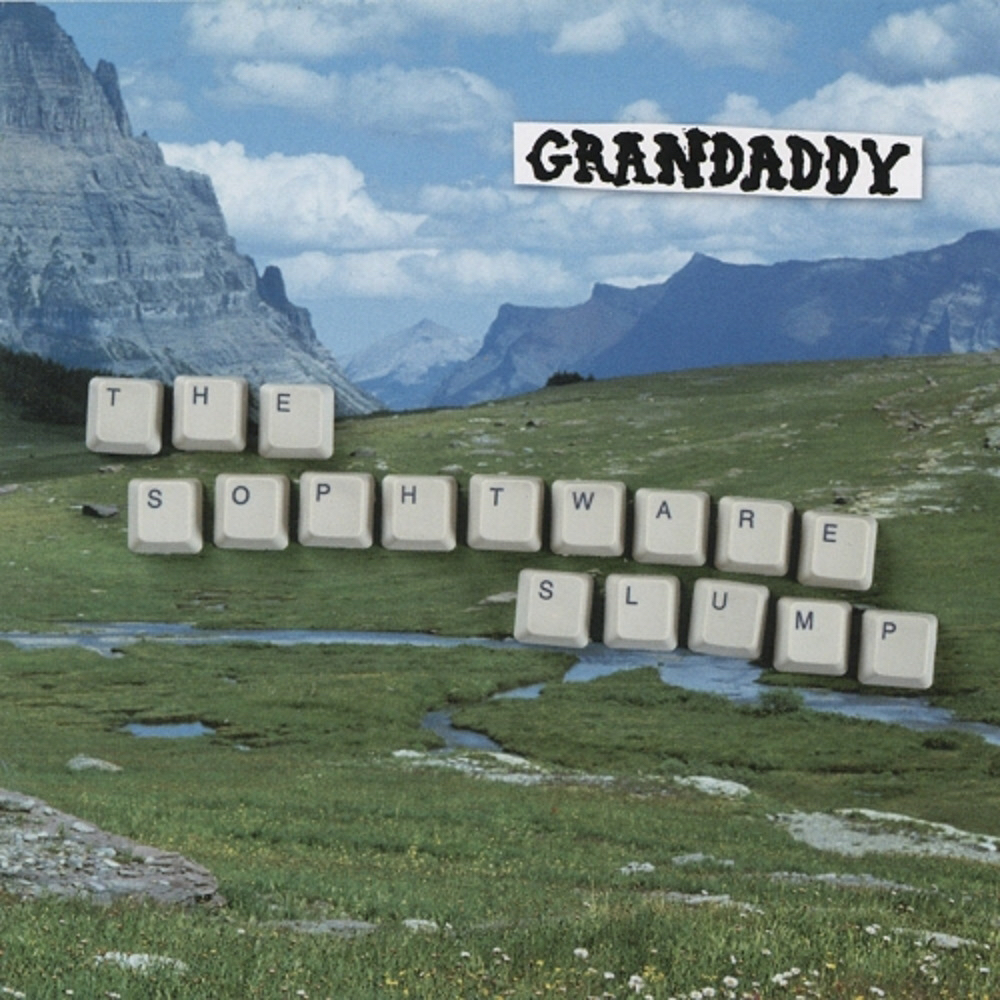

These were the kinds of stories Lytle was telling all over The Sophtware Slump. Grandaddy's second album, released 20 years ago today, essentially answered the question: What if West Coast indie, but sci-fi? Or, given the music's vast prog-rock horizons and Lytle's skepticism toward all the technology encroaching on Earth's natural order: What if Radiohead, but West Coast indie? Grandaddy hailed from Modesto -- Spanish for "modest" -- and the punny title was appropriately self-deprecating. It made a lot of thematic sense, too: This was a concept LP about the slouching citizens of a disappointing dystopia, trapped on a tapped-out planet full of useless junk. But far from a dreaded second-album misstep, The Sophtware Slump stands as a quirky, ambitious landmark in the overgrown ruins of Y2K-era indie.

Lytle formed Grandaddy in 1992 after his burgeoning pro skateboard career was unceremoniously ended by a knee injury. Early gigs at skate parks plus a longstanding devotion to the Maximumrocknroll radio show led to Grandaddy playing uptempo punk rock at first, but by the time they released their debut album Under The Western Freeway in 1997, their style had softened into a rustic yet electronic spin on the scrappy underground guitar noodlings of Pavement and Built To Spill. The album's best, most enduring song, "A.M. 180," paired fuzzed-out power chords with a deviously catchy keyboard riff that sounded futuristic and amateurish all at once. The other tracks toyed around with a less overtly poppy variations of this aesthetic, a sort of ramshackle space-age slacker rock that, as it turned out, lent itself perfectly to songs about the American West decaying into a technological wasteland.

Lytle once told The Telegraph that, like famous Modesto native George Lucas, he grew up with "nothing better to do than dream up robots." The similarity ran deeper than that. On the dearly departed website The Outline earlier this year, John Ganz wrote about the "used future look" of the original Star Wars movies: "Lots of the ships and robots were dinged up, rusted, and peeling." The scenes Lytle conjures on The Sophtware Slump are similarly chintzy; it is a universe where you can visit the "Broken Household Appliance National Forest" and miners who've moved on to other planets can catch a glimpse of any location on Earth via something called a dial-a-view.

In 2013, Lytle told The Line Of Best Fit about the other career paths he'd considered: "I had park ranger, conservation corps, firefighter… even a mailman, just because I knew I’d be able to be outside walking around." In 2006, having relocated to Montana, he told a reporter from The Guardian, "I can't talk right now. I'm about to get on a horse." That abiding love for the great outdoors is unmissable on The Sophtware Slump, particularly on its lead single "The Crystal Lake," a snappy pop-rocker that enjoyed some MTV2 airplay and was a minor hit in the UK. Over a surging array of guitar arpeggios and flickering keyboard sounds, Lytle admits, "Should never've left the crystal lake/ For parties full of folks who flake." The lake is presented as an almost divine entity that reflects back deep truths about whoever peers into its ripples, revealing the hollowness of so many pursuits. As the tune builds to its explosive climax, Lytle concludes, "I gotta get out of here."

Fittingly, Lytle recorded the album alone in a remote farmhouse, "in my boxer shorts, bent over keyboards with sweat dripping off my forehead, frustrated, hungover, and trying to call my coke dealer." In that 2006Guardian interview, he recalls the role of drugs in the Grandaddy recording process: "Speedy stay-uppy stuff mostly. Preferably coke. But if there was anything else around I'd jump all over that." The Sophtware Slump is not most people's idea of cocaine music, except maybe its nine-minute, multi-segmented opening track "He's Simple, He's Dumb, He's The Pilot," a song grandiose enough to rival the overblown epics of Oasis' Be Here Now. Yet Lytle displays a defter touch than the Gallagher brothers at their peak of excess, weaving references to David Bowie's "Space Oddity" and the Rolling Stones' "2000 Man" into a gentle fable about an astronaut struggling to readjust to life back home. Elsewhere Lytle serves up charmingly off-kilter pop ("Hewlett's Daughter"), minimalist piano balladry ("Underneath The Weeping Willow"), and a sludgy rock 'n' roll joyride ("Chartsengrafs").

Still, the album is never more poignant than when he zeroes in on Jed, the android with the drinking problem, who'd been introduced on the prior year's Signal To Snow Ratio EP. (It dropped a few months after the premiere of Futurama, another brilliant sci-fi featuring a drunken robot, so it's hard not to envision Bender whenever the Jed character pops up.) Like all great science fiction, Jed's tragedy shows us something meaningful about the human condition -- in this case, both our own dysfunction and fragility and the tendency to poison even our greatest creations eventually. The aforementioned "Jed The Humanoid" sums up the character's whole doomed arc, but late in the tracklist we're provided further details in a reprise called "Jed's Other Poem (Beautiful Ground)" sung from Jed's perspective. He gets defensive about the severity of his addiction. He laments that he hasn't settled down with a family like other androids his age. "I try to sing it funny like Beck, but it's bringing me down," Lytle sings as Jed -- a genuinely absurd lyric, but one that plays as devastating in context.

Such is the genius of The Sophtware Slump. Like Lucas, Lytle had established an entire alternate universe in sound and substance, strung together in peculiar vignettes that left much to the imagination. It was a triumph, but Grandaddy weren't done evolving yet. Three years later, they'd return with Sumday, an album that ditched the mythology and experimentation in favor of '70s-inspired hi-fi splendor. At the time, Lytle called it "a reflection of everything we've been working towards" and "the ultimate Grandaddy record." Maybe, but some might argue that the ultimate Grandaddy record is the one they rolled out in the year 2000, the grand treatise about the tortured love triangle between mankind, his planet, and the works of his hand. Like the clunky machinery that dots its landscape, The Sophtware Slump may now seem like an outdated relic, but boot it up and you'll discover it still works wonders.