In The Number Ones, I'm reviewing every single #1 single in the history of the Billboard Hot 100, starting with the chart's beginning, in 1958, and working my way up into the present.

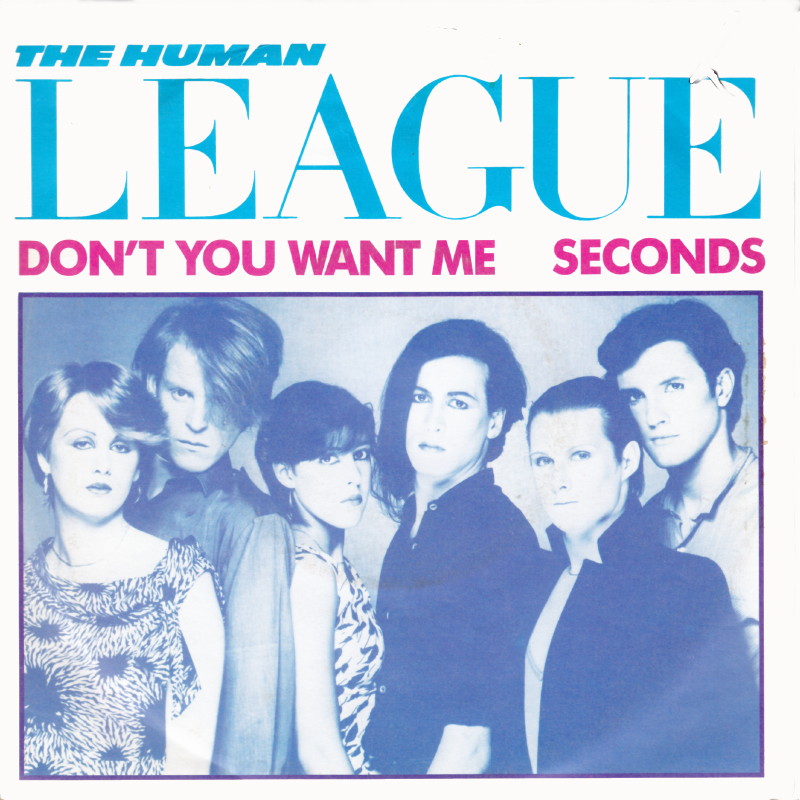

The Human League - "Don't You Want Me"

HIT #1: July 3, 1982

STAYED AT #1: 3 weeks

To Americans first encountering the Human League in 1982, the band's name must've come off as a high-concept joke. Everything about the Human League ran against every possible notion of flesh-and-blood rock 'n' roll. The band had no guitarist and no drummer -- just three singers and three synth players. In interviews, they said that guitars were "archaic." Lead singer Philip Oakey delivered his lyrics in a flat, stentorian monotone, sounding like the robotic clone of David Bowie. And yet the Human League's American breakthrough was a pocket melodrama about jealousy and possessiveness and spite and vulnerability -- perhaps the most human of emotions.

The circumstances that led to "Don't You Want Me" hitting big in the US are simply impossible to replicate. All sorts of cultural circumstances had to work together, in concert. MTV, hungry for enough music videos to fill its 24-hour programming, had to move on from established rock stars and into the ranks of British art-school weirdos. British art-school weirdos had to be emboldened by the punk rock explosion of the late '70s, and then they had to move on to synthesizers and riffs on Hollywood glamor. And the Human League had to go through their own unlikely evolution.

The Human League had started out in the grey, industrial UK city of Sheffield in the late '70s. Computer operators Martyn Ware and Ian Craig Marsh had a group called the Future, and they aimed, without much success, to fuse pop with stark, expressionist electronic music. Ware and Marsh needed a singer, so they signed up Oakey, a high-school friend of both who didn't have any musical experience but who was good-looking and who dressed flamboyantly. With Oakey on board, Ware changed the group's name to the Human League, taking the name from a sci-fi board game called Starforce: Alpha Centauri.

In 1979, the Human League signed to Virgin Records, and their first two albums are cold, unforgiving sci-fi bloopiness. Those albums have a few bangers, like "Being Boiled," but they did not sell. Soon enough, the Human League became art-school punchlines. Northern Irish punks the Undertones clowned the Human League by name on their 1980 single "My Perfect Cousin," which became a top-10 UK hit. Since none of the Human League's own singles had come anywhere near the top 10, that had to sting.

That same year, the Human League effectively broke up. Ware and Marsh had argued bitterly with Oakey, who wanted to make pop music, not icy synth provocations. Finally, Ware and Marsh left the band, splitting off to form a new group called Heaven 17. (Heaven 17's highest-charting US single -- at least until Bill Gates singlehandedly spearheads the Heaven 17 revival -- is 1982's "Let Me Go," which peaked at #32.) Perhaps ironically, Heaven 17 ended up making pop music that also worked as icy synth provocation. So did the Human League.

Oakey kept the Human League name, but this, at least at first, was more of a burden than a boon. The Human League had been booked for a UK tour before Ware and Marsh left, and Oakey had to get a new band together quickly. He learned to play keyboards, and so did Philip Adrian Wright, who'd been a Human League member even though he'd only previously been responsible for the visuals of their live shows. (On Dare, the Human League's breakout third album, Wright is still credited with "slides.")

Oakey wanted a female backup singer who could sing the high parts that Ware had previously sung, and he wound up with two. Oakey headed out to a new wave night at a Sheffield club called Crazy Daisy, and he found two teenage best friends, Joanne Catherall and Susan Ann Sulley. Like Oakey himself, Catherall and Sulley had absolutely no previous musical experience, but they looked cool and moved well. (These are probably still the best qualifications for any prospective pop star.) Catherall and Sulley already had tickets to see the Human League on that upcoming tour. Instead, they became members of the band. When the Human League recorded the 1981 album Dare, Catherall and Sulley were still in high school, and they had to take the bus from Sheffield to the recording studio in Reading.

For Dare, the Human League were a whole new group. The final addition was keyboardist Jo Callis, a former guitarist for the punk band the Rezillos. (Callis, recruited for songwriting purposes, didn't know how to play keyboard before he joined the Human League.) Virgin paired the group up with producer Martin Rushent, who'd mostly worked with punk bands like the Buzzcocks and the Stranglers but who knew how to layer up synth sounds. The group's new sound kept the frozen synth textures of the early Human League records, but it added a melodic brightness that they'd never had before. It clicked right away. The album's first single, "The Sound Of The Crowd," peaked at #12 in the UK. The next two, "Love Action (I Believe In Love)" and "Open Your Heart," both went top-10. Suddenly, the Human League were new wave stars. And then came "Don't You Want Me."

Phil Oakey's "Don't You Want Me" lyrics had been inspired by a photo story in a women's magazine and by A Star Is Born. He wrote the song as a dialogue. Oakey's character is some kind of aging power-broker type, despondent and heartbroken after being dumped by a woman who he'd found working as a waitress in a cock-taiiil bar. Susan Ann Sulley, who up to that point had only sung backup to Oakey, took the lead as the girl, who tries to let the guy down easy but who clearly wants to get the fuck away from him immediately. (The #1 song in America on the date of Sulley's birth: The Four Seasons' "Walk Like A Man.") In real life, Oakey had started dating Joanne Catherall; they'd remain together until 1990.

On the first verse of "Don't You Want Me," Oakey sounds stern and commanding -- as if he can't believe that this girl would have the nerve to think that she could move on from him. "Success has been so easy for you," he sings, implying that maybe it hasn't been so easy for him. When he straight-up threatens her -- "I can put you back down, too" -- we start to get the idea that he's wounded and shattered and powerless. On the chorus, he confirms it, his naked need increasing with every syllable: "You'd better change it back or we will both! Be! Sor! Ry!" He starts out sounding bored, and he winds up desperate.

As for Sulley, she remains bored throughout. She lets Oakey know, right away, that he wasn't responsible for her success, that he was just a vector for it: "Even then, I knew I'd find a much better place, either with or without you." She says that their five years together have been "such good times," and it sounds like a dismissal. Her "I still love you" is totally perfunctory, a mechanical nothing that doesn't come off the least bit sincere. Sulley's lack of experience is part of what makes it great; it lends a conversational ease to the way she brushes Oakey off. All he can do in response is sing the chorus a bunch more times. When Sulley joins in, she sounds like she's humoring him. The song presents a tangled mess of feeling, and it tells a story of what happens when a power dynamic is reversed.

It also slaps. "Don't You Want Me" is the first hit song ever to be powered by Linn's LM-1 drum machine. This doohickey, which would become one of Prince's favorite instruments, samples real drum sounds rather than electronic ones, which gives some dimension to what's unmistakably a programmed track. The keyboard lines push up against each other, mirroring the struggle of the song's two characters. The song is spare and elegant. It foregrounds its singers and the drama that they weave, but it keeps pulsing out hooks underneath them. It's pop magic.

Phil Oakey didn't think it was pop magic. The initial version of "Don't You Want Me" was chilly and confrontational art-pop, which was how he'd envisioned it. But Martin Rushent remixed the song, layering up the synths and making it sound like candy. Oakey hated this. "Don't You Want Me" is the last song on Dare, and Oakey thought it was just filler, the worst song on the album. (When Oakey talks about "Don't You Want Me" now, it sounds like he still hates it.) But Virgin A&R exec Simon Draper loved the song, and he overruled Oakey, demanding that the Human League release it as the fourth single from Dare.

Draper even approved an expensive music video from the Irish director Steve Barron, who will turn out to be hugely important figure to this column. (Barron also directed the 1990 movie Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles, which rules.) The clip is a neat bit of old-school Hollywood iconography that draws attention, again and again, to layers of its own artificiality. It was perfect for MTV. "Don't You Want Me" blew up in the UK, topping the singles chart for five weeks and becoming the 1981 Christmas #1. In the summer of 1982, as MTV gained in influence, "Don't You Want Me" was nearly as successful in the US.

The Human League had already been huge in the UK before the song hit, but "Don't You Want Me" was the first Human League single to chart in America. It might be the first true MTV-era #1, the hit that established how the new medium was changing the rules for pop success. The new British synthpop stars, covered in makeup and cloaked in layers of irony, were built for a visual medium like the music video. American soft-rock studio-musician types, who'd been making a lot of hits in the very early '80s, could not hope to compete. In 1983, Rolling Stone proclaimed that the pouty synth kids made up a "Second British Invasion," and the magazine claimed that "Don't You Want Me" had been the "breakthrough song" for this new wave.

"Don't You Want Me" wasn't really the first synthpop song to hit #1 in the US; M's similarly detached "Pop Muzik" had landed two and a half years earlier. And "Don't You Want Me" didn't singlehandedly alter the shape of the charts. UK synthpop was still at least a year away from commercial dominance in America. (This was changing, though. Soft Cell's stark take on Gloria Jones' "Tainted Love," peaked at #8 behind "Don't You Want Me." "Tainted Love" is a 9.) But "Don't You Want Me" still stands as a monument to preening, bleepy melodrama. It was a hard act to follow, but the Human League will be in this column again.

GRADE: 10/10

BONUS BEATS: Here's the Farm's video for their dance-rock cover of "Don't You Want Me," a top-20 UK hit in 1992:

https://youtube.com/watch?v=C5beMgNEqM0

BONUS BONUS BEATS: Here's the "Don't You Want Me" cover that Stephin Merritt's Future Bible Heroes project recorded for the 2000 Human League tribute compilation Reproductions:

BONUS BONUS BONUS BEATS: Here's Lil B rapping over a "Don't You Want Me" sample on 2011's "Trapped In BaseWorld," a song from his incredibly strange early-'00s mixtape run:

BONUS BONUS BONUS BONUS BEATS: Here's hook-singer Yandel interpolating the "Don't You Want Me" chorus on Pitbull's 2015 Spanish-language track "No Puedo Más":

(Yandel's old duo Wisin Y Yandel's highest-charting single, 2005's "Rakata," peaked at #85. Yandel also guested on Ozuna's 2018 "Única" remix, which peaked at #72. Pitbull will eventually appear in this column.)