You have to be ready. That's the lesson. An upstart two-piece garage-blues band from Detroit, one that has a couple of records out on a subgenre-specific indie label, probably will not get the chance to change the world, to capture the hearts of millions. But sometimes, circumstances change. Sometimes, the planet's cultural rotation wobbles a bit, allowing for certain things to slip through and strike collective nerves. If that happens, if the axis tilts just right, you need to have your shit fully figured out. You need to be ready to go. De Stijl turns 20 tomorrow, and if the album proves anything, it's that the White Stripes were ready.

The White Stripes released De Stijl, their second album, less than a year after they dropped their self-titled debut. The album also came out a couple of months after Meg White divorced Jack White, a rupture that somehow did not kill the band for good. When the band released De Stijl, Jack White was still running his ill-fated Third Man Upholstery business; he only shuttered it so that the band could head out on tour behind the album. De Stijl came out on Sympathy For The Record Industry, a now-dormant garage-punk label best-known as the home of the Muffs and the Oblivians and Billy Childish, the place where Rocket From The Crypt and Turbonegro would release the vinyl editions of their major-label albums. Nobody involved could've possibly believed that the White Stripes would become stars, and yet the duo carried themselves that way anyway.

Everyone who encountered the White Stripes in the De Stijl era has a "holy shit" story about it. Me, when my roommate Janet brought home a copy of De Stijl and played "You're Pretty Good Looking (For A Girl)" on the CD boombox in the living room of an art-student flophouse: "Holy shit." My wife, when she saw the White Stripes open for Sleater-Kinney at the 9:30 Club: "Holy shit." The White Stripes were bright and bold and haughty and theatrical. They had riffs and hooks and swagger. They stood out. If you heard them once, you wanted to hear more. And if you looked into what they were doing, there was plenty beyond the riffs and hooks and swagger.

The summer of 2000 was not the pre-internet era, but you couldn't readily find out anything you might want to know about a band like the White Stripes. You couldn't find De Stijl at Best Buy, or even at most mom-and-pop record shops. (I think I found mine at one of the stores on South Street in Philadelphia, when I was visiting friends there.) They'd already built up a story about how they were siblings, even though they were really a divorced couple. But at the time, I didn't know the real story or the fake one. It wasn't broadcast everywhere. The White Stripes were just two people in a CD booklet who had the same last name, and I figured it was a Ramones-type stage-name situation, which was at least partially true. The band had cultivated this whole mysterious persona for themselves, and I had no idea. I just knew I liked them.

These were the final days of the era when didn't necessarily know that much about the bands youl liked. Maybe message boards and zines were discussing the particularities of the Stripes' narrative, but most of us learned about these bands just by catching their live shows, or by listening to the records. This environment seemed to suit the White Stripes just fine; when the internet necessarily became a greater part of the band's existence, Jack White couldn't stop bitching about it in interviews. Maybe he was right to worry. There was, after all, a whole lot to learn from the records.

When I finally sat down with De Stijl, I remember initially being disappointed that more of the songs didn't strut as hard as "You're Pretty Good Looking." I got over it. The other songs veered towards laser-eyed psychedelia, or acoustic brooding, or absurdist blues pastiche. "I'm Bound To Pack It Up" was a bald Led Zeppelin bite in an era when nobody else was even attempting to nod in that band's direction. "Apple Blossom" was like the Kinks doing a nursery rhyme. "Why Can't You Be Nicer To Me?" was what might've happened if a mid-tantrum eight-year-old had gotten his hands on a Hendrix riff.

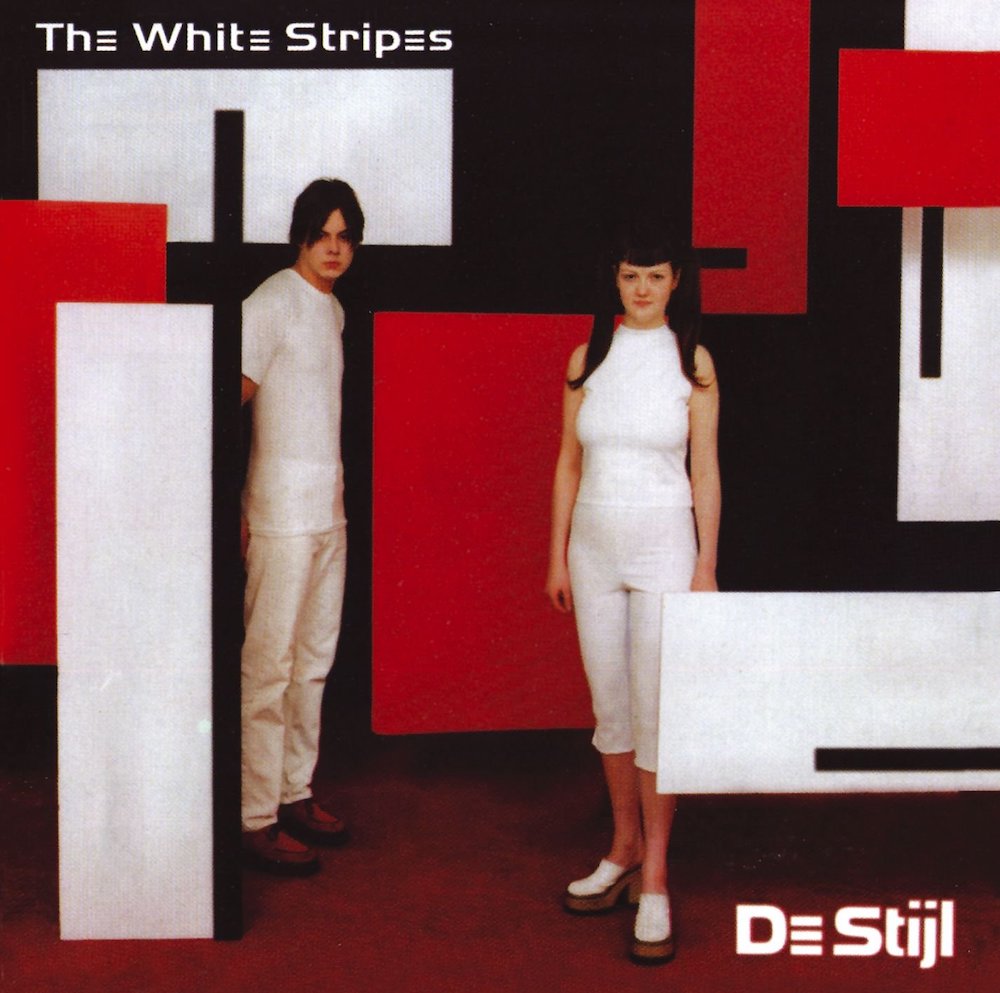

The band looked like they made electroclash, and they had broadcast their aesthetic and their color scheme all over the CD case. The album was dedicated to two dead men, one Dutch furniture designer and one Georgia blues player. There were layers there. It was weird.

In retrospect, the remarkable thing about De Stijl is the way it flaunts Jack White's love of faded Delta blues records without sounding anything like those records. On the album, the band covers Son House and Blind Willie McTell, but they sound more like some hard, rudimentary pastiche of Zeppelin, Sabbath, the Stones, the Beatles, the Kinks, and every other British band that heard those American blues records and tried to remake them. There's also a ton of Detroit in the band's sound -- not just the Stooges and the MC5, but Alice Cooper and Mitch Ryder & The Detroit Wheels and early Bob Seger, too. It's not punk, and it's not garage rock, though those are in the mix somewhere, too.

Jack White's presence on the album is huge. An editor of mine once said that White's whole selling point is that he was Robert Plant and Jimmy Page at the same time, and that's been stuck in my head ever since. The idea that a Detroit upholsterer could be both of those guys is patently ridiculous, but White believed it. He snorts and preens and flirts and sasses and yelps. He unleashes blazing distorto-leads. He hammers at pianos. His tics, like the weird and fey fixation on grade-school romance, are already in the mix on De Stijl. He's ambitious enough to keep pushing his sound in different directions from song to song, a gift that would really blossom on the band's next LP.

White's lyrics on De Stijl are simple but elliptical. Sometimes, they're a little too fixated on his romantic perception of old blues outlaws. Sometimes, when he's covering their songs, he sings about slapping women around: "Now baby, ashes to ashes, sand to sand/ When I hit you, mama, then you feel my hand." Sometimes, in his own obsessive-introvert perspective, he'll write his own lyrics about that same kind of possessiveness: "I got a little bird/ I'm gonna take her home/ Put her in a cage/ And disconnect the phone." Mostly, White is focused on how he can appeal to some unnamed and unknowable woman, and it's hard not to wonder how many of his words are about the bandmate who would divorce him before the album hit shelves.

That bandmate's contributions are massively important. Now that Jack White's solo career has lasted about as long as his White Stripes run, it's clear that he can't manage anything as potent on his own as he did with his old band. Meg White was a steadying, grounding influence. Her minimal, thumping percussion always anchors the record. And everytime she does something even a little bit different -- a shaker, a tambourine, a cymbal tap -- it jumps right out. Her steady pulse reminds me of AC/DC drummer Phil Rudd, who famously refused to play fill for decades and who always gave that band its unshowy forward drive.

The White Stripes were truly out of step in 2000. At that time, the bands that college students tended to love were into layered sound effects and emotional abstraction: Sigur Rós, Modest Mouse, Radiohead circa Kid A. Critics on both sides of the Atlantic were falling for drowsy knit-hat depressives like Badly Drawn Boy and Doves, or for record-collector sophisticates like Clinic and Broadcast. The Jon Spencer Blues Explosion, standard-bearers for Crypt Records-style garage-blues all through the '90s, had started to turn toward fractured beat experiments.

The White Stripes didn't have anything to do with any of that, and they weren't a part of any of those conversations. Instead, they operated within a healthy garage rock underground. I spent the summer of 2000 working door at the Knitting Factory in New York. I saw a lot of garage-adjacent bands that gave me a lot of "holy shit" reactions: The Rondelles, the Bangs, Cobra Verde. None of them became stars. None of them were ready. If the White Stripes had just remained in that world for a few more records and then broken up, they would've been legends within it. Maybe they would've become a touring institution like Rocket From The Crypt, or a perennial cult favorite like the Gories. Instead, the sands shifted, and they became something else.

About a year after De Stijl, the British music press, tired of hyping up post-Radiohead simps and mad drum 'n' bass scientists with elaborate goatees, fell in love with a New York boy band who sounded like Television, and a whole lot of garage-rock trend pieces followed. When that happened, there was this ambitious Detroit duo sitting right there. They were hard and catchy and ostentatious. They looked cool. They had a weird built-in backstory. They were made for the moment. They were ready.