In The Number Ones, I'm reviewing every single #1 single in the history of the Billboard Hot 100, starting with the chart's beginning, in 1958, and working my way up into the present.

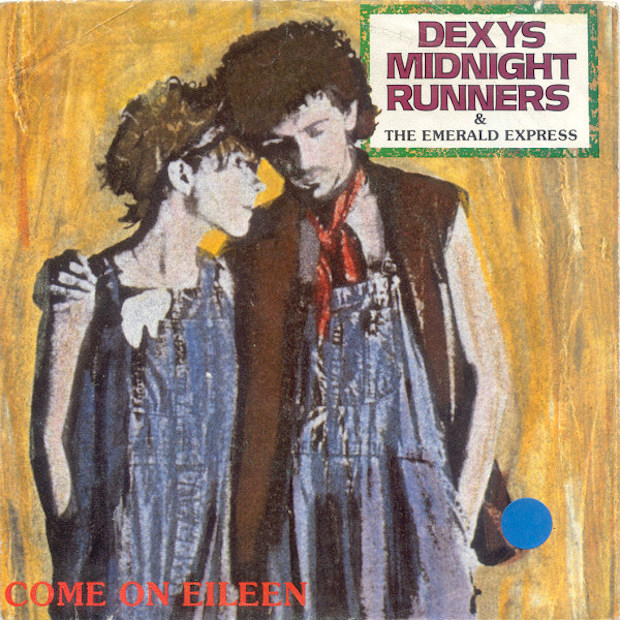

Dexys Midnight Runners - "Come On Eileen"

HIT #1: April 23, 1983

STAYED AT #1: 1 week

Context is a funny thing. In the UK, Dexys Midnight Runners were a troubled institution -- a chaotic young band who couldn't stop breaking apart and reforming and who still managed to tap into some dizzy zeitgeist more than once. In the US, Dexys are classic one-hit wonders: Scraggly and goofy-looking British weirdos in overalls who were all over MTV for a couple of months and who then disappeared forever. On two sides of the Atlantic, this one band has two vastly different legacies.

But where "Come On Eileen" is concerned, the greater context of Dexys Midnight Runners almost doesn't matter. The effect was the same. "Come On Eileen" was a #1 hit in both countries, and it remains a fondly remembered piece of pop-music history. You could revere "Come On Eileen" as a classic, or you could see it as an embarrassing little short-lived gimmick. Either way, when you're three drinks deep and "Come On Eileen" comes on at the bar, you're singing along.

https://youtube.com/watch?v=O_i9t7h8AgY&feature=emb_title

The version of Dexys Midnight Runners that briefly interrupted Michael Jackson's reign in the spring of Thriller was not the first version of Dexys Midnight Runners, and it wasn't the last. Kevin Rowland and Kevin Archer started the band together in 1978 in the Northern English city of Birmingham. Both of them had been in the Killjoys, a punk band who'd been around for a couple of years and released one single. By the time they started Dexys, Rowland was sick of punk. He had a different idea in mind.

Originally, Dexys was inspired by Northern soul, a UK subculture that I have always found fascinating. Long before raves were a thing, pasty and underemployed British kids would stay up all night dancing frantically to the fastest, most unhinged obscure American R&B records they could find, and a whole subculture, with its own fashion and slang and drugs, came out of it. (Dexys Midnight Runners were named for dextroamphetamine, a type of speed that these kids would take to enable the staying-up-all-night part.)

Dexys all dressed in uniform, cosplaying as Robert De Niro in Mean Streets, and they imagined themselves as a UK equivalent to American soul. Their debut album was called Searching For The Young Soul Rebels, and it yielded the grand, spirited singalong "Geno," a #1 hit in the UK.

Rowland was a famously rough bandleader. He drilled the group hard in rehearsals, dictated the dress code, and wouldn't let them talk to the press. Eventually, virtually the entire band quit. Archer and a few others left Dexys to form a new band called Blue Ox Babes. Only Rowland and trombone player "Big" Jim Paterson remained. So Rowland recruited a new Dexys lineup, gave them a new uniform, and put them all on a strict fitness regime, insisting that they all go running together.

The first few records from the new Dexys lineup weren't terribly successful, but then Rowland heard demos of some Blue Ox Babes songs. Rowland loved the way Blue Ox Babes combined Celtic strings with uptempo soul beats, and he basically decided to steal this style for Dexys. Rowland tried to get all the horn players to learn to play strings. When that didn't work out, Rowland recruited violinist Helen Bevington, a music school student, from the Blue Ox Babes. Rowland got Bevington to change her name to Helen O'Hara, since it sounded more Irish, and he convinced her to bring in a few more string players from her music school.

This lineup of Dexys Midnight Runners didn't last long, either, but Rowland kept it together long enough for Dexys to record Too-Rye-Ay, their second album. While working on the new album, he assigned the band a whole new look: Those grimy and patched-together overalls from the "Come On Eileen" video. Rowland co-wrote "Come On Eileen" with band members Jim Patterson and Kevin Adams, though he later admitted that he'd stolen the basic sound from his ex-bandmate Kevin Archer. Rowland was very much trying to make a hit when he came up with "Come On Eileen"; Dexys needed one badly. They got it.

I don't think I'd ever really given the "Come On Eileen" lyrics much thought before sitting down to write this piece, but there's a lot going on in the song. Rowland wrote those lyrics about getting into a sexual relationship with a friend when he was in his teens. Catholic guilt hangs over the song; Rowland tells the girl that his thoughts "verge on dirty" when he looks at her. He gets majestically sentimental about his parents and their music. He thinks of their mothers listening to "poor old Johnny Ray," the dependably bummed-out pre-rock American pop idol, and he thinks that they could sing Irish lullabies just like their fathers. But he doesn't want to end up like his father.

https://youtube.com/watch?v=JhVIMAiKZ-A

Rowland sings about Birmingham's miners and factory workers with a sort of terror. To him, they're "beaten down" and "so resigned to what their fate is." But Rowland dares to imagine something better for himself and Eileen: "We're far too young and clever." That's when "Come On Eileen" becomes a song about sex, one of our most dependable, if short-lived, means of escape. Rowland wants Eileen to "take off everything," and suddenly the song turns into a giddy chant, speeding up and slowing down tempos recklessly.

"Come On Eileen" takes its intro from "Believe Me, If All Those Endearing Young Charms," an Irish folk song that Thomas Moore (not the saint) wrote in 1808, and its big hook is suspiciously close to the one on "A Man Like Me," the 1972 single from Jimmy James, a Jamaican singer beloved on the Northern soul scene. (This is another one of those cases where someone probably would've been sued if it happened today.) "Believe Me, If All Those Endearing Young Charms" and "A Man Like Me" don't necessarily have much in common with one another, but Rowland draws them together through horny desperation and fired-up intensity and a big clompy-clomp rhythm, and he makes them work.

A big part of the charm of "Come On Eileen" is Rowland's voice. He's clearly not the soul singer that he wants to be, but he doesn't let that stop him. He yelps and wails as hard as he can, and his Northern English honk bulldozes through all the strings and horns around him. When "Come On Eileen" turns into a big mass singalong, it finds a certain drinking-song grandeur. Producers Clive Langer and Alan Winstanley had already done a lot of work with London ska goons Madness, and both the clean clumsiness of the "Come On Eileen" beat and the gang-shout chorus could've come straight from that band. (In the US, Madness' highest-charting single, 1982's "Our House," peaked at #7. It's a 9.)

I've never had the dizzy love for "Come On Eileen" that some people have. It's too busy, with all those gratuitous tempo changes, and the beat is too awkward and funkless for the Celtic soul pastiche that they're going for. But it's an elegantly written song about real, intense feelings, and it's got a monster hook. Besides that, a mass singalong remains a joyous thing. I've had nights that were greatly improved by the existence of "Come On Eileen." You probably have, too.

In the US, where the plight of kids trying to escape from Northern English factory towns doesn't necessarily have a whole lot of cultural relevance, "Come On Eileen" was at least a little bit of a novelty. MTV did that. The "Come On Eileen" video came from director Julien Temple, auteur of the disowned Sex Pistols movie The Great Rock And Roll Swindle. In the video, everyone wears the extremely goofy Dexys uniform, whether or not they're members of the band. The Eileen of the video is Máire Fahey, sister of Bananarama member Siobhan. (Bananarama will eventually appear in this column. Much later on, Siobhan Fahey would briefly join a touring lineup of Dexys.) The video was bright and memorable and absurd, and it got plenty of MTV play. Based on everything I've read, Americans received "Come On Eileen" the same way we received all these other new strange and shiny British hits, even though it had fiddles and banjos instead of keyboards and drum machines.

Dexys had a few more hits in the UK, but "Come On Eileen" was their one dance with the American cultural consciousness. Only one more Dexys single charted in the US: 1983's "The Celtic Soul Brothers," which peaked at #86. Dexys continued to crank through new band members at an absurd rate, and their next album, 1985's Don't Stand Me Down, was a commercial disappointment on both sides of the Atlantic. Dexys broke up in 1987, and Kevin Rowland went on to a hitless solo career. He had problems with addiction and depression, and for a while in the '90s, he was on welfare.

Rowland put together a new version of Dexys, featuring some of the old members, in 2003, and they've released a couple of reunion albums while continuing to crank through band members at an alarming rate. At this point, Dexys Midnight Runners has dozens of ex-members, but they continue to exist, and "Come On Eileen" continues to incite mass singalongs.

GRADE: 8/10

BONUS BEATS: Here's the scene from 1995's Tommy Boy where Chris Farley and David Spade enthusiastically sing along to "Come On Eileen" and a couple of other songs:

(R.E.M.'s 1987 single "It's The End Of The World As We Know It (And I Feel Fine)" peaked at #69. Mocedades' 1973 Eurovision runner-up "Eres Tú" peaked at #9. It's an 8.)

BONUS BONUS BEATS: The Orange County band Save Ferris had a 1997 alt-rock radio hit with their ska-punk cover of "Come On Eileen." Here it is:

BONUS BONUS BONUS BEATS: Here's "Come On Eileen" soundtracking Jonah Hill's drug-freakout scene in the 2010 movie "Get Him To The Greek":

(Puff Daddy will eventually appear in this column.)

BONUS BONUS BONUS BONUS BEATS: Here's the scene from 2012's The Perks Of Being A Wallflower where Ezra Miller, Emma Watson, and Logan Lerman dance to "Come On Eileen":

BONUS BONUS BONUS BONUS BONUS BEATS: Here's "Come On Eileen" soundtracking an impulsive car chase in a 2017 episode of Preacher:

(There's also a great bit in a recent episode of What We Do In The Shadows where a vampire claims that he wrote "Come On Eileen" hundreds of years ago, but I can't find video of that scene online.)