There should be a word for it: The thing before the thing. In the summer of 2000, rock music was in a weird place. If you wanted to hear exciting new sounds on the radio, you weren't listening to the rock stations. Most of the big names of the early-'90s alt-rock wave -- the ones who had survived, anyway -- were thrashing around at various levels of irrelevance. The people who'd taken over for them were a decidedly mixed bag.

In America, nü metal was in its dominant phase, though nobody who'd seen the flames at Woodstock '99 could pretend that there was anything remotely progressive about it. The alternative-rock gatekeepers no longer had any firm idea of what constituted "alternative." Post-grunge yarlers had conquered modern-rock radio. Spin was putting Creed and Papa Roach and Matchbox 20 on its cover. In the UK, the last embers of Britpop had died away, and the big names on the festival circuit were bands like Stereophonics and Travis, groups who tried to imagine what would've happened if Radiohead had decided to become the Counting Crows. Coldplay were imminent. Something had to change.

In retrospect, plenty was changing. Bands like the White Stripes and the Hives were building press buzz and excited little followings. "Emo" had become something other than a term that punk bands used to make fun of other punk bands. Post-rock and alt-country and Matador-style indie rock were all doing fine for themselves. Soon enough, the British press would get all excited about a band of pouty-lipped rich kids from New York, and a different cycle would start off. But in the meantime, there was the Dandy Warhols.

It all looks pretty silly in retrospect. With the 2004 documentary Dig!, the Dandy Warhols effectively trapped a moment in amber. That film sought to tell the story of two Portland frenemy bands, the Dandys and the Brian Jonestown Massacre. The film wanted us to know that the BJM were the real-deal troubled artistic geniuses, while the Dandys were the crass careerists who managed to become stars. What it really showed, though, was two groups of eminently punchable assholes didn't have the tiniest shred of self-awareness among them. The only real difference was that the BJM were self-destructive buffoons, while the Dandys were relatively functional buffoons. Both bands hated the movie, but the images it left were indelible.

https://youtube.com/watch?v=g6m99JChkvY

The Dandys didn't really need the movie to make themselves look ridiculous. They'd resigned themselves to it the moment that they decided to call themselves the Dandy Warhols. (That's not even a clever band name! Andy Warhol was already a dandy! At least "Brian Jonestown Massacre" halfway works as a pun.) Frontman Courtney Taylor-Taylor was an ex-mechanic who looked like a male model and who thought it would be funny to give himself that last name. If Taylor-Taylor ever wrote a single sincere lyric in his life, then he made sure to deliver it with enough of a smirk that nobody would hear it that way.

The Dandys formed in Portland in the mid-'90s, and they were snapped up by Capitol in the final reverberations of the post-Nirvana earthquake. Their first Capitol album, 1997's ...The Dandy Warhols Come Down, was droney, blissy dream-rock with an edge of sneery depravity and occasional flashes of power-pop rigor. The band managed a minor alt-rock radio presence with "Not If You Were The Last Junkie On Earth," a song that seriously uses the phrase "heroin is so passé" as its hook. Three years later, though, something clicked, and the Dandys made both the biggest and the best album of their lives. They just made it a year too early.

Thirteen Tales Of Urban Bohemia, the album that the Dandys released that summer -- 20 years ago this Saturday, to be exact -- is a quietly brilliant piece of rumpled majesty and glammy insouciance. The Dandys slather sustain all over their strummy acoustic guitars and reverb all over their backing harmonies. Their beats shimmy and strut and groove hard enough to support a Massive Attack remix. Tambourines shake and sparkle. Instead of bass, there's Zia McCabe's rumbling analog synth. Big guitar riffs rise up out of nowhere and fade away elegantly. Musical decisions that could've been disastrous -- like the trumpet player from Cake tootling away on one song, or the former DMC contest winner DJ Scratch wikky-wikkying through another -- instead add playful grandeur. The whole thing just works.

Musically, Thirteen Tales is a bunch of American Spiritualized fans imagining what might've happened if Jason Pierce had been more into the Rolling Stones than the Velvet Underground. Along the way, maybe they try to get into some of those dusty-fried post-Beck radio rotations, the same way the Fun Lovin' Criminals had done a few years earlier. There are a couple of joke country songs and a couple of Ennio Morricone hoo-hah grunts amidst all the stormy guitars. The sound is completely tied to its era, but it's the best version of that sound. And in retrospect, it's possible to hear that sound as a sort of connective tissue -- the strand that ties the self-assured pretty boys of Suede to the self-assured pretty boys of the Strokes.

Self-assured pretty boy Courtney Taylor-Taylor doesn't do himself too many lyrical favors on Thirteen Tales. Everything he does on Thirteen Tales has an ironic distance to it -- and sometimes a pretentious one, as when he uses "Mohammed" and "Nietzsche" as song titles. You can hear the pursed lip in his drawl. Every song is about sex, drugs, or some combination thereof, and Taylor-Taylor clearly delights in depicting broke, bummy young Portland as some kind of carnal wonderland.

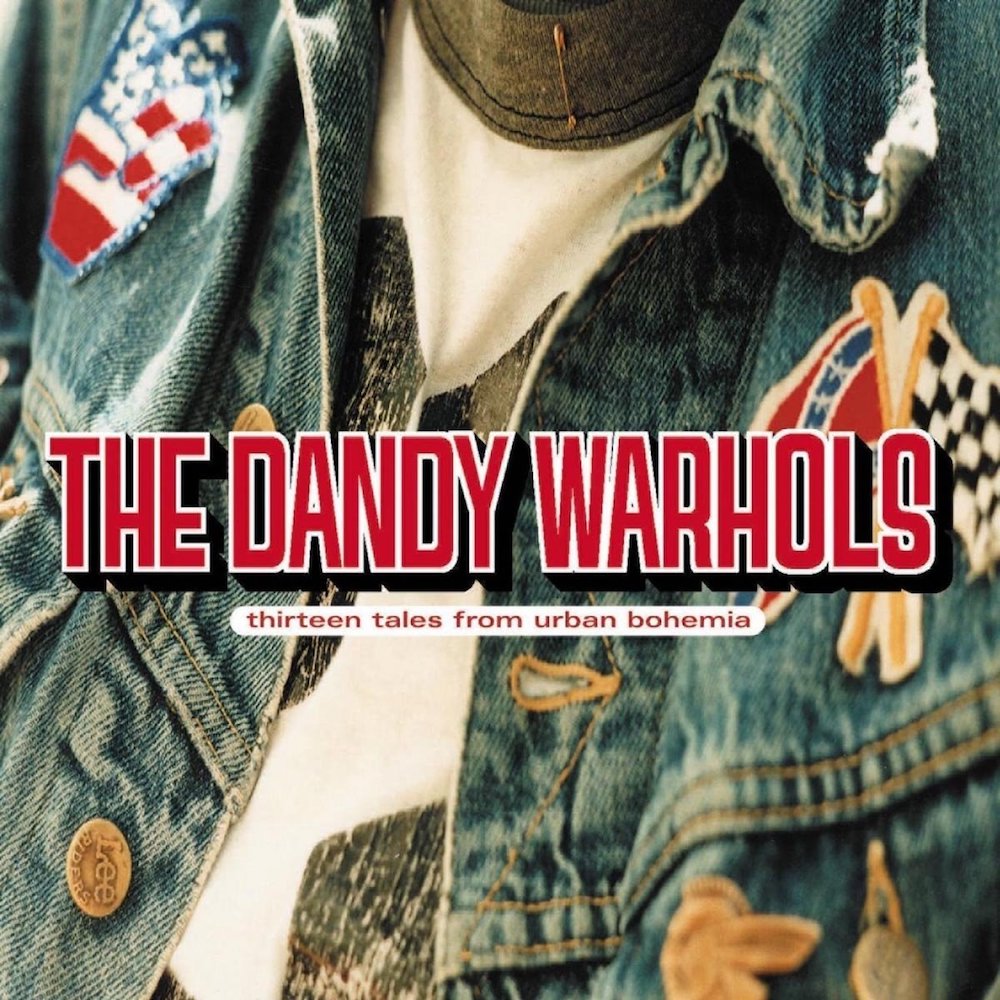

When Taylor-Taylor brags on Thirteen Tales -- "I got a beautiful new Asian girlfriend/ She comes over and hangs around for days in my bed/ You can't seriously believe I'm thinking about you, man" -- it's hard to tell whether he's being ironic or not. (This was a time when people thought it was cool to wear ironic Confederate-flag patches on their jean jackets, and then to put those jean jackets on their album covers.) He sounds like a complete dick, but he's got charisma and allure, too.

On "Bohemian Like You," the song that would turn out to be the band's big hit, Taylor-Taylor shows the way people fuck in his world. Taylor-Taylor, to the girl who he's banging and who still lives with her ex: "I guess it's fair if he always pays the rent/ And he doesn't get all bent about sleeping on the couch when I'm there." That's the "Meet Me In The Bathroom" mentality, one year earlier.

"Bohemian Like You" is a delirious power-pop banger, but it might've faded away if someone at the cell-phone company Vodafone hadn't put it in a TV ad. In the wake of that commercial, "Bohemian Like You" went into the UK top 10, peaking at #5. The album went gold in the UK and Australia. It didn't leave much of a dent in the US, but the Dandy Warhols weren't the type of band to care about that. That summer, I saw them play a thoroughly zooted set at the Bowery Ballroom that climaxed, if I'm remembering this right, with the band singing happy birthday to Genesis P-Orridge. They were a total mess, and I loved them.

The Dandy Warhols never really benefitted from the hype that surrounded the Strokes a year later. Maybe they were between album cycles at the wrong time. Maybe they were already a known quantity. Maybe they were just too fucking irritating a presence. But they still had some big moments. David Bowie was a fan, and he sang with the Dandys at his Meltdown festival in 2002. They recorded the follow-up album, 2003's Welcome To The Monkey House, with Bowie producer Tony Visconti and with Duran Duran's Nick Rhodes, and that album's single "We Used To Be Friends" became the Veronica Mars theme song. They're still going. They put out an album last year.

But 20 years after its release, Thirteen Tales From Urban Bohemia still stands as their crowning achievement, a great rock record that also offers a snapshot of a moment before a moment. The Dandy Warhols didn't leave a stamp on history, exactly. There is no Dandy Warhols era. But they helped carve a space for a certain shimmying swagger. If that's their enduring legacy, then fair enough. The Dandy Warhols weren't the thing. They were the thing before the thing. There are worse things to be.