Imagine what you think of blackness. Then reimagine it, again and again, until it is true, until it is righteous, until it is real. That is Beyoncé’s new goal.

Black Is King, her new visual album, is a testament to the continual strength and power of Black culture. In the project, which debuted last Friday on Disney+, Beyoncé makes a definitive statement for the underlying power of Black creativity and art around the world. We are foundational, she argues. There is little, if anything, that can diminish or destroy Black art, not even the peril of colonialism which ripped Black people apart in the first place. From Johannesburg to Ghana to London to Belgium to the United States, Beyoncé creates a vision of Black people that says we are not defined by the differences of our experiences. No, we are united in our collective stories which tell of a greater, deeper lineage of what it means to be Black. And it is this lineage, intangible but very present, that continues to survive and thrive to this day.

In the film, Beyoncé reimagines the story of The Lion King, utilizing music from The Lion King: The Gift, her original soundtrack created for the 2019 live-action retelling of the classic story.Inspired by the biblical stories of Joseph and Moses, as well as William Shakespeare's Hamlet, the 1994 version of The Lion King was a cultural phenomenon.

But viewed through the lens of 2020, the film’s holes are apparent. Namely, it strangely, blatantly devalues and whitewashes its setting. The Lion King is a story of family and legacy and overcoming strife. But it is also a story rooted in the sights and sounds and diversity of Africa. The 2019 live-action version made the story and its characters hyper-realistic, sometimes in an uncomfortable, uncanny valley manner. But it still lacked a level of authenticity driven by the environment in which it takes place.

Black Is King, in contrast, is a truer retelling of the fictional story, infusing it with the sort of history and humanity stripped from its predecessors. It is a response to and perhaps even a confrontation of the limits of the storytelling of the 1994 and 2019 versions of The Lion King. If The Lion King is a story firmly rooted in the blood and soil of the past kingdoms and present legacy of Africa, why is it so stripped of our culture?

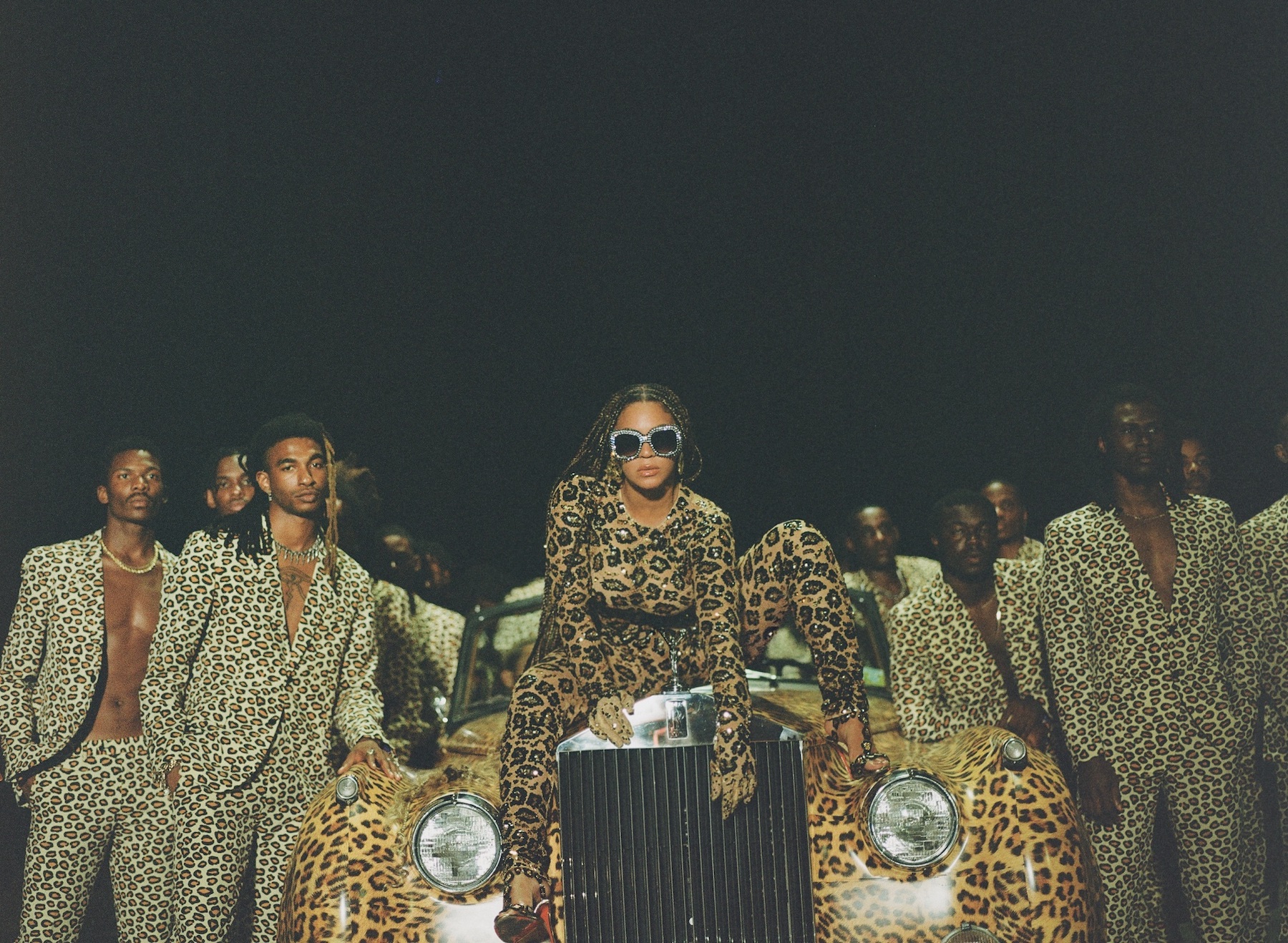

Rather than leave the question open for scrutiny, Black Is King makes right the bones of the story. What is pushed to the forefront here is beauty, is character, is rhythm, is precision, is glory. And each moment of the film becomes a showcase of Black diasporic culture, design, and aesthetics. Whether it be the landscape or the costumes (curated by costume designer Zerina Akers), Black Is King says, without question, we are here and we are beautiful.

And while the visuals are colorful and provocative, it is the music that fuels the storytelling. It is the music that truly underscores the thesis of the project -- that we are a regal, powerful race of people spread across the world and making impactful, revolutionary art. And while our music may sound different on the surface from one country to another (and even one city to the next), there is still a unifying depth, heart and soul that connects all Black sounds -- and thus, all Black people -- everywhere. As a soundtrack, The Gift is a collaborative project highlighting artists and producers from around the globe.

"My Power," the album's standout, includes vocals by Beyoncé and a large collective of artists, everyone from Philly rapper Tierra Whack to Busiswa, the South African singer-songwriter and poet, to Yemi Alade, a Nigerian Afropop artist. The track, a propulsive Afrobeat wonder, includes a memorable chorus recited by Whack: "They'll never take my power, my power, my power/ They feel a way/ Oh wow." It’s a boastful, prideful call to arms that perfectly encapsulates Beyoncé’s theory of unification. And in the film, it comes at the moment before Simba returns home to reclaim his home. In lyric and in visual, it is a fuel and fire for taking what is often stripped from Black people around the world -- land, spirit, and ultimately power -- in both fictional and true stories.

"Brown Skin Girl," released last year during the promotional cycle for the live-action version of The Lion King, operates similarly in its musical construction. It features Brooklyn-born, Guyanese American rapper SAINt JHN, and Nigerian singer WizKid, and the song is a luscious, loving ode to the beauty of Black women. Upon first listen, it would be a sweet if not simple track. But Black Is King brings the song to life. Some of the track’s noted beauties -- from Naomi Campbell to Lupita Nyong’o to Kelly Rowland -- make appearances in the film. During "Brown Skin Girl," these women and many more dance, smile, and lovingly embrace, dressed in deeply-hued and formal gowns.

Blue Ivy, Beyoncé’s first-born daughter, makes an intensely felt appearance here. Her winsome vocals pepper the track, and she stands as the true purpose of the song. Black is King and its brilliant songs ask us about legacy. Whose legacy do we protect and uphold? What do we teach the generations behind us? How do we uplift their power, their strength, their beauty? By reaffirming the truth and vitality of their existence. As a parallel to the Lion King story, this aligns with the moment when Simba is reunited with his childhood friend and first love Nala. Here, Beyoncé invokes the wonder and awe such a character would feel upon seeing Nala’s beauty and, more broadly, the beautiful rich brown skin of Black women.

At the end of the film, we learn that Black Is King is dedicated to Beyoncé‘s son, Sir Carter, and the film then seems at one with its storytelling. This is a project connecting future Black lives to their roots in the past through visual and sonic storytelling of the present. In a video statement aired on Good Morning America, Beyoncé said that Black Is King means "Black is regal and rich in history, in purpose, and in lineage." And this is true and real and deeply felt from the very first moments of the film.

What is a reimagining that can’t also be a re-cleaning, a repurposing, a redefining of what it means to be Black, both here, where Beyoncé was born and lives, as well as around the world, where the Black diaspora thrives despite it all? "My hope for this film is it shifts the global perception of the word Black, which has always meant inspiration and love and strength and beauty to me," Beyoncé said. From a viewer's perspective, her goal was achieved.