When Universal Pictures started the promotion cycle for Scott Pilgrim Vs. The World, they clearly didn’t know which angle to push. To be fair, the movie has got a lot going on. Edgar Wright’s geeky action-comedy romance, an adaptation of Bryan Lee O’Malley’s graphic novel series, follows 22-year-old slacker Scott Pilgrim (Michael Cera) as he falls head over heels for Ramona Flowers (Mary Elizabeth Winstead), the new alt-girl in town whose seven evil exes vow to tear him apart. The movie is a nonstop sprint through magical realism that’s stuffed with comic book-style swipe cuts, martial arts-indebted fight scenes, video game visual effects, and the perfectly mundane realities of life in a local indie rock band.

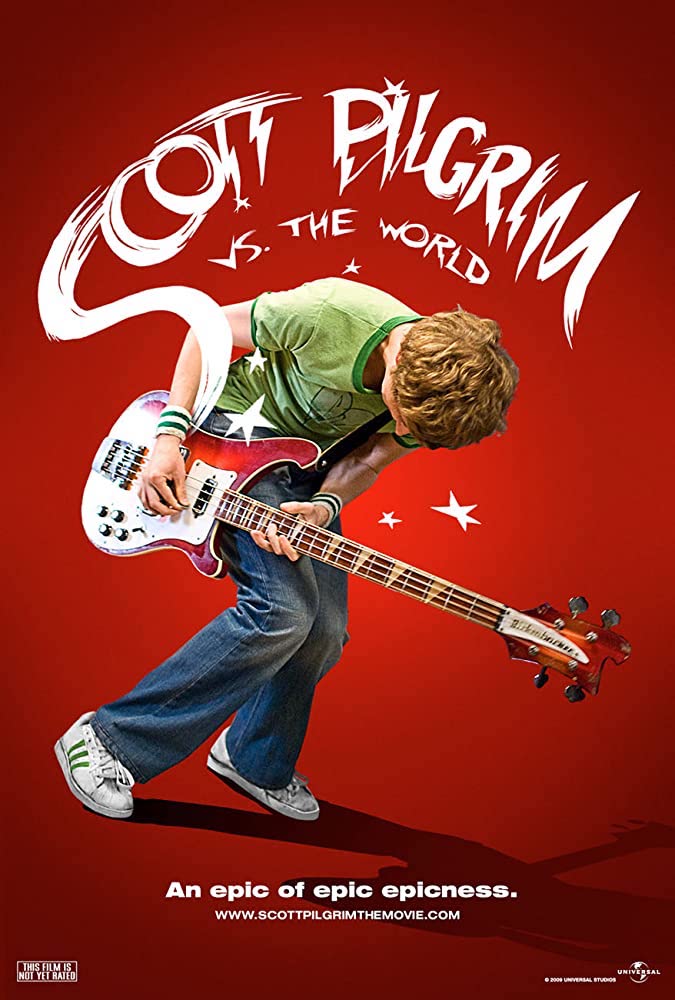

Yet no matter how much praise its monumental Comic-Con debut garnered or how many LCD Soundsystem and the Prodigy songs they placed in trailers, Universal struggled to sell a mainstream audience on the movie. Following its August 13th release date in 2010 -- 10 years ago today -- Scott Pilgrim Vs. The World was declared a box-office flop, making roughly one sixth of its $60 million budget back during its opening weekend. It was released on DVD three months later.

How funny that all is in hindsight. In the decade since its release, Scott Pilgrim Vs. The World quickly became a verifiable cult classic. It’s spawned a constant stream of cosplayers and endless hair dye inspiration. It’s got a litany of quotes that consistently resurface as Twitter callbacks. The movie is still regularly screened in theaters across the country. Additionally, it caught several of its actors on the cusp of career-defining roles: Chris Evans inked his Captain America deal months earlier, Aubrey Plaza got Parks And Recreation the same week she was accepted for Scott Pilgrim, Anna Kendrick was cast in Pitch Perfect the following year. Others in the movie later became household names as well, with Brie Larson winning an Academy Award for Room in 2016 before transforming into Captain Marvel, and Kieran Culkin receiving his long-overdue spotlight just recently with Succession. No wonder last month’s table read reunion already has over a million views.

Scott Pilgrim Vs. The World is a witty, ambitious romp that holds up to and rewards multiple viewings. The past decade has also proven that the movie is a surprisingly adept time capsule for 2010s indie rock thanks to a self-aware script, an in-the-know soundtrack, and a handful of fictional-yet-convincing bands. Even side jokes, like mocking the transition of veganism as an ethical stance in punk to unavoidable moral grandstanding within indie rock, feel ahead of their time.

Unknowingly, Scott Pilgrim Vs. The World was released in a hugely transitional moment for underground music. Up until then, indie rock felt like a secret subculture hidden in small clubs and MP3 blogs. In 2010, that facade vanished. Arcade Fire’s album The Suburbs debuted at the #1 spot on the Billboard 200 and, come winter, won the Grammy for Album Of The Year, beating Lady Gaga, Katy Perry, Eminem, and Lady Antebellum. Soon, the changing music landscape allowed other indie bands to ascend to previously unforeseen prominence as well. At the same time, long-held standards of coolness vs. geekiness were upended, as comic books experienced a cinematic renaissance. Scott Pilgrim just happened to cross-pollinate these fandoms before it was normal to do so.

I spoke to Wright, as well as several of the actors and musicians and writers involved, about how it all came to life -- and how they look back on it now 10 years later.

To pull off the genre fusion in Scott Pilgrim, Wright recreated the unique dynamic of a musical -- specifically, where characters are allowed to break into song and immediately return to regular conversation, no questions asked. “There was something about that Venn diagram that I was taken with, especially those Hong Kong action films from the ‘70s and ‘80s and how they were almost structured like musicals,” says Wright.

While he and screenwriter Michael Bacall revisited dozens of music-related movies while penning the script -- ranging from camp classic Beyond The Valley Of The Dolls to the Dandy Warhols and Brian Jonestown Massacre documentary Dig! -- they were especially influenced by Brian De Palma’s Phantom Of The Paradise. “We explicitly nod to that one because of its Phil Spector-y villain," Wright says. "It was like a spiritual forebear. Jason Schwartzman’s character was drawn in a similar way in the book, so I wanted to make him feel like a 2010 version of Phil Spector."

With source material rooted in Toronto’s flourishing local music scene during the mid-'00s -- including beloved, beat-up music venues like Club Rockit and Lee’s Palace -- the script captures what it’s like to be a 20-something musician bumping into hungover pals at the shitty pizza place post-gig or digging through the racks at thrift stores on the weekend. “There’s a lot of little Canadian easter eggs in the movie and it almost feels like inside baseball,” says Cera.

Alison Pill, who plays Sex Bob-Omb drummer Kim Pine and grew up nearby, agrees. “Shooting a scene at Pizza Pizza across from Honest Ed’s brought me so much extreme joy," she remembers. "A lot of people think Pizza Pizza is not good, but I disagree ... it’s delicious bad-good!”

Even Broken Social Scene's Brendan Canning himself, who contributed to both the score and soundtrack, felt transported back in time while watching the movie. “I went on set once when they were shooting around the corner from my house at a famous coffee chain here called Second Cup,” says Canning. “It was things like that. They didn’t shoot at Starbucks; they shot at Second Cup. It was a very authentic depiction of Toronto, especially in that era.”

This homage to an '00s indie rock scene takes shape in the character of Scott Pilgrim, too. He’s a stringbean hipster with shaggy hair, an oversized parka, and “tragically Canadian sensibilities.” In many ways, he’s just a college graduate trying to figure out the responsibilities of adulthood while playing bass in his friend’s band, Sex Bob-Omb. As Cera puts it, Pilgrim is a “lovable moron.” But Pilgrim is also a regular asshole who dates an underage high schooler, bails on band practice, drops some racist comments, and feigns destitution in pop-culture ringer tees while playing a vintage Rickenbacker -- a bass that costs $2,000 on a very good day, but that he, of course, swiped from his younger brother.

He’s a mirror image of all the guys who looked up to ashen, lanky, rich kids fronting buzz bands back then. Maybe it’s because his friends constantly call him out on his bullshit, or maybe it’s because Cera portrays him with an innate humility, but Pilgrim maintains enough underdog appeal for you to still root for him as he grows -- even if he’s the archetype of a selfish, straight, white dude who skates his way to musical success and multiple girlfriends.

To Bacall, the character was instantly recognizable -- he knew plenty of guys like that in his 20s. “What’s really refreshing about his specific journey is that initially, his underlying insecurity is what makes him likable: he has some growing to do," Bacall says. "There’s always a push for the characters to be likable, especially in lighter American fare, and the danger of that is having a protagonist who feels very fake. Bryan [Lee O’Malley] really did the heavy lifting in terms of Scott’s arc. It was an enjoyable challenge not to try to cover those flaws up in the adaptation, but to make sure that they were put front and center in what’s clearly a coming-of-age story.”

It should go without saying that both O’Malley and Wright are music nerds at their core. By joining forces on this adaptation, they began feeding off one another in a way that elevated their ideas. O’Malley knew exactly how to drop music references in the graphic novels that could translate into a movie, and Wright knew how to bring O’Malley’s comic book and video game references to life in the movie without any of the clunkiness that could invite, be it Akira taglines or Street Fighter setups. The two began mailing one another mixtapes with different themes, like music they imagined the characters enjoying, songs they listened to while editing, or tracks they loved from the 2000s. “It was like we were educating one another about bands,” says Wright.

If the script outlines the realities of the late-'00s music world, then the soundtrack colors it in. Handpicked with care by Wright and O’Malley to emphasize their respective senses of humor and encyclopedic knowledge, the songs don’t just fit the mood of the scene or the character’s personality; they’re tongue-in-cheek jokes for any viewer who’s a fellow musical Rolodex. It’s T. Rex's “Teenage Dream” blasting full volume when Pilgrim mentally celebrates landing his dream girl, a Beachwood Sparks cover of Sade’s “By Your Side” playing during his makeout session with Flowers, the quiet echoes of “Anthems For A Seventeen-Year Old Girl” while his 17-year-old girlfriend Knives Chau looks at him broken-hearted from afar, and the brilliant use of “Under My Thumb” as Gideon Graves whisks Flowers off via a controlling brain chip.

Sure enough, the film’s official soundtrack was a hit. While everyone was busy focusing on box office numbers that month, the soundtrack quietly climbed to the #2 spot on the Billboard Soundtracks chart and the #24 spot on the Billboard 200, staying on the latter for nearly two months. The most qualified person to comment on its success just so happens to be the movie’s music supervisor, Kathy Nelson. Her résumé is intimidating, to say the least, as she’s responsible for creating and securing some of the most iconic movie soundtracks of all time, including Repo Man, High Fidelity, Coyote Ugly, Pulp Fiction, Dangerous Minds, and Eternal Sunshine Of The Spotless Mind.

Though her job was comparatively easier for Scott Pilgrim due to Wright and O’Malley having already determined which songs to use, Nelson found herself as engaged and delighted as if she was the one picking tracks. “I’ve worked on a lot of movies, but rarely have I had so much fun in the moment and while looking back like I did with Scott Pilgrim,” says Nelson. “Edgar truly has such an excitement and passion about him. It’s infectious. Creatively, he used the music with such perfection and specificity that it made my job incredibly easy. It was in the same vein as working with Tarantino, where he knows exactly what he wants and your job is just to get it. That’s rare. Edgar has a broader knowledge of music than even I do!”

Meanwhile, the rest of the film’s music was being orchestrated by Nigel Godrich. The Radiohead producer met Wright at a mutual friend’s wedding eight years before they began working on Scott Pilgrim. Unsurprisingly, the two hit it off talking about music and decided to keep in touch. “Because the movie required so much original music that was actually going to be in the film with fictional bands playing it, I thought a good way to make it sound authentic would be to have a real superstar music producer do it,” says Wright, laughing. “Then I asked if he ever wanted to score a movie and he said yeah.”

Thus Godrich was brought onboard as Scott Pilgrim’s music producer, taking on the tasks of composing the score and organizing original music for the film’s bands. Instead of leaning into guitar rock on the score, he reclined into ambience and subtle melodies, balancing the movie’s intensity with understated moods. On various tracks, he’s joined by mashup artist Osymyso, hip-hop producer Dan The Automator, Broken Social Scene’s Kevin Drew and Brendan Canning, and a roundtable of esteemed session musicians, with each person drawing out specific elements. To date, it’s the only film score Godrich has ever composed.

“When I saw [the finished film] after spending all of this time on the score, I remember being like, ‘Turn the music up! Turn it up! I can’t hear it!’” laughs Godrich. “I’ve been revisiting the music for the anniversary and honestly it’s really lovely! I think it’s a music fan’s movie, so thankfully people will pay attention to those details that I spent so much time on. It was a dream project and a lot of fun, especially because it wasn’t a regular score." You get the sense that Godrich would only entertain doing this with Wright, partially because of his disposition and partially because of his own music obsessions.

"It’s a genre hopping, stylistic pastiche where every scene has a reference: other kung-fu movies, specific chase scenes, John Carpenter, Goblin, all these things Edgar loves because he’s a huge consumer of music and film music," Godrich continues. "You know, I’ve been asked to do a lot of scoring and I generally don’t do it because you’re the first person who gets blamed if something’s not working. But being friends with Edgar, I knew he would protect me from those larger trap doors of the Hollywood system, and he did.”

Originally, Wright and Bacall planned to omit any scenes where the bands in Scott Pilgrim actually performed. The way they saw it, why force an audience to watch the awkwardness of actors pretending to be musicians, a shtick that rarely goes well? “It’s hard to think of a fake band in a film that you actually want to see and hear,” says Bacall. “It was two people in a room looking at this massive task ahead of us, knowing that this was going to be a very difficult adaptation, and identifying the music as one of the more difficult elements of it.”

However, they soon realized it was within their power to bring the fictional bands of Scott Pilgrim to life if they got real bands to soundtrack them. That’s where Godrich came in. “In Toronto, there’s a lot of homegrown talent, especially with Broken Social Scene and Metric,” says Godrich. “Everybody was really up for it and it felt like one big, extended, musical party."

Within the movie's universe, the biggest band by far is the Clash At Demonhead, a cheeky alt-rock trio named after the first NES game O’Malley owned. They play the role of the arrogant rock band, complete with slick production and unavoidable promo flyers, with Brie Larson as singer Envy Adams, Brandon Routh as bassist Todd Ingram, and real-life drummer Tennessee Thomas (Nice As Fuck, the Like) as drummer Lynette Guycott. Routh spent hours imagining who his character was and how he could inflate his personality even more. “This guy punched a hole in the moon, so I wanted to take the dialogue and do my own interpretation -- not so much worrying about the words, but how his voice feels,” says Routh.

That larger-than-life energy translated to screen naturally, giving the costume department time to shine. Laura Jean Shannon, the film's costume designer, went everywhere to find the perfect pieces: snagging Adams’ trademark red heels from a sex shop, asking a friend to design serpent-inspired jewelry, and tailoring every outfit within an inch of its life. “The Clash At Demonhead were basically a little sinister while still being high fashion,” says Shannon. “We wanted the feeling you got when reading the books to come across when you saw them: Scott’s anxiety levels, his triggered nerves, all of that. We really played into the mystique, allure, and mood that surrounds bands, where a famous band has that unobtainable coolness that fans may aspire to be like. Eventually my design board felt like a tome.”

When the Clash At Demonhead finally take the stage, it feels like a reckoning. O’Malley originally imagined the band as an amalgam of Metric and Pony Da Look. So it’s almost surreal when, shrouded in darkness, they launch into the opening bass notes of “Black Sheep,” a then-unreleased Metric song that has since become a staple of their live repertoire -- though Metric frontwoman Emily Haines admits it took the band a while to realize just how popular that song and that movie scene had become.

“I remember Edgar saying, ‘We need an unreleased song from you that is completely over the top, an exaggerated expression of the band.’ And I said, ‘I’ve got just the song for you!’” says Haines. She credits it as perfect timing, as Metric recorded “Black Sheep” during the initial round of writing sessions for Fantasies, but eventually left it off the album due to its glam-rock panache not meshing with the other tracks. In the film, though, it’s a perfect fit, so much so that they filmed an entire music video from the performance. To date, that clip has 15 million views -- over 10 million more than the song itself has.

https://youtube.com/watch?v=iGkqIRypwEQ

Even the best music movies can fall victim to inaccurate representation of the music industry. The worst culprits are the fictional bands whose strumming doesn’t line up with the music they’re playing, an unavoidable reminder that everything you’re watching is fake. Wright was incredibly committed to making sure the artists in Scott Pilgrim could walk the walk, so he paired the actors with music coaches to help guide them. For Larson, there wasn’t major work to do, as she already pursued voice lessons growing up and released an album of pop-rock du jour in 2005 (including an Avril Lavigne B-side cover) when she was 16 years old. While Larson had to sing over the “Black Sheep” instrumental in the movie, it was arguably Routh who had more studying up to do.

The former Superman star played trumpet in marching band as a kid, among various other instruments, but had never played bass guitar. After working with Beck’s guitar teacher in Los Angeles for several weeks, Routh got to put his new skills to the test during the Clash At Demonhead’s band practices in a rented rehearsal space in Toronto. “We jammed, we bonded, and we shot group photos for the album cover and posters. We had time to cement our friendship as bandmates, and, without talking about it first, our energies really matched the douchiness that our characters had in their own way,” laughs Routh. “It was very immersive and, honestly, it made me feel like I was in a real band."

Technically, that wasn’t even the hardest part for Routh. After the Clash At Demonhead’s concert, Ingram and Pilgrim get into a fight that revolves around a bass battle. The duel sees each bassist launching into a series of increasingly difficult riffs to out-do one another, and ultimately Pilgrim loses. That puts the onus on Routh to be the technically superior bassist. It’s not just goofy chords, either. Godrich rang up Justin Meldal-Johnsen and Jason Falkner, both legends in their own right, to ask if they were free to recreate this graphic novel scene for a film.

“I got them in a room together, gave them the parameters, and they just did their thing. It was basically a real bass battle with them improvising in the studio,” says Godrich. In the scene, their intensity and drive comes through, with each bass part speeding up as they progress, including a callback to the bassline from Final Fantasy II. It’s just nerdy enough to feel challenging, but just fun enough to inspire viewers to try it themselves.

And then there’s Crash And The Boys, a petulant group of goths who write songs like flash-bang grenades and squeeze memorable jokes into their curt onscreen time. Arguably the only member who lets their rage out visually is their eight-year-old drummer, who habitually flips people off and even committed to the bit in her audition tape. Though it doesn’t sound like a shoe-in fit for Broken Social Scene, the daydreaming indie rock titans of Toronto’s music scene, Godrich knew they had enough range to pull it off.

“Edgar gave us a photograph, like an 8x10 of the drummer and what she looks like. As soon as I saw her, I thought, ‘Oh, yeah. D.R.I. meets Napalm Death,’” says Canning with a chuckle. “You need a four-second-long song? Got it. I wanted to nail that. It was fun to think about hardcore bands I like and flex a similar muscle as them, especially since I don’t get to do that in Broken Social Scene. Just on a purely personal note, it was really fun how those sessions came together with me, Kevin [Drew], Ohad [Benchetrit], and Charles [Spearin]. It was just a really nice time, like one big cosmic fairytale.”

While this was happening, Godrich got in touch with Keigo Oyamada, the artist behind Cornelius and Flipper’s Guitar, to help pen music for the fictional electronic duo the Katayanagi Twins. In the movie, Sex Bob-Omb must face the twins during an amp-versus-amp battle. Lifting melodies directly from those transposed in O’Malley’s graphic novels, Oyamada and Godrich retooled glittery synth work into something more menacing and powerful, the type of peppy electronica that could reasonably overpower a grunge pop band playing at the same time. The trick is in their gear, as the twins have endless stacks of amps and cabinets to make their songs unavoidably loud. That high voltage strength results in a spirit-like duel between a giant gorilla and serpentine dragon birthed from the two bands’ live music. According to Bacall, he wrote the first draft of that scene while smoking a joint in Quentin Tarantino’s backyard and blasting music through his headphones. Wright was living in the director’s guest house at the time, and he passed that scene off to Bacall when he dipped out for a meeting.

“With the Katayanagi twins, there wasn’t a lot of work to be done with them as characters -- mystery was the operative word behind them -- but in terms of their musical qualities, the goal was sheer, absurd volume and sonic force," Bacall says. The scene was inspired by Bacall's love of Sunn O))) and his shock at their enormous backline, then his amusement when they finally started playing and he could see his shirt moving from the force of the sound. "So the idea of having enough speaker cabinets to literally blow someone off a stage in this scene made me laugh," he adds. "It makes Sex Bob-Omb, the little band that could, overcoming technical inferiority by sheer force of passion feel really fun.”

Out of all of these artists, by far the most popular fictional band to come from the movie is Sex Bob-Omb. With Pilgrim on bass, Stephen Stills on lead vocals and guitar, Kim Pine on drums, and Young Neil on “understudy bass” -- their names a play on Crosby, Stills, Nash & Young -- Sex Bob-Omb are a supposedly shitty indie rock band that finds success during Pilgrim’s ongoing battles against Flowers’ exes. But in reality, they’re far cooler, balancing an air of informality and passion through fuzzed-out slacker rock.

When Wright’s initial plan for Be Your Own Pet to soundtrack Sex Bob-Omb was abruptly halted due to their breakup, Godrich suggested they ask Beck instead. “I’m a huge Beck fan, but I don’t think I would have thought to ask him because at that point in his career he had started to move on from that sound,” says Wright. To their surprise, Beck agreed to the role almost instantly. They sent him scenes, comic art, animatics, and inflated artwork from the novels to put around his garage where he practices. On Friday night, Wright gave Beck a list of the scenes where his songs would be used and a short brief on the band. On Sunday evening, Beck sent them 24 songs on a CD.

"I think for him it was an excuse to make these garage tunes again without pressure," Godrich says. "Especially since you can’t decide if [Sex Bob-Omb] are genius or rubbish."

“I couldn’t believe it. I vividly remember driving around with Nigel listening to the CD real loud,” says Wright. “It was Nigel’s idea to use the songs as is. He said, ‘If you want it to be authentic, like this band has been rehearsing it in their house, why would you make it more slick? It’s authentic and raw and he’s done it with his eight-track. I think this is it.'" The songs were the result of Beck and Brian Le Barton jamming, and most of the songs -- including "Garbage Truck," "Summertime," and "Threshold" -- came from that weekend. "It was extraordinary," Wright recalls. "It’s exactly what you dream your indie rock band in your living room could sound like, and he did it in two days.”

Every reason why Sex Bob-Omb is an exciting band stems from their inherent casualness. Whereas movie bands traditionally inhabit the overwrought effort of a pop star or rock entity seen through an industry executive’s eyes, Sex Bob-Omb are just a couple of 20-somethings who look like your classmates and are just OK at their instruments. There’s a believability to their insecurity. Their songs ride along ragged, simple riffs and charmingly mindless lyrics with technical errors sprinkled in. “The funny thing about that is that the actors had to learn the mistakes in the songs, too, like those changes in tempo or missed notes where whoever was recording was probably focused elsewhere,” says Wright.

Then comes their overall style, which Wright compares to the Flying Burrito Brothers. Stills wears western shirts with artsy appliques from a designer in Marfa, Texas. Pine sticks to rotating shades of green and athleisure zip-ups. Pilgrim sports handmade tees promoting everything from Rock Band to the Smashing Pumpkins, and his Adidas always match. “All of the shirts were custom-made and screen printed to get the exact color schemes correct,” says Shannon. “We actually worked with Adidas to get all of his sneakers and had to get special permission to paint them different colors. It’s hilarious looking back because Scott’s outfits always had to look like it was no big deal, but there was an incredible amount of effort and time that went into designing, creating, and treating all of the clothing.”

https://youtube.com/watch?v=KI0xsw3x7EY

Watching Scott Pilgrim, it’s easy to forget that Sex Bob-Omb aren’t a real band. The actors are playing their real instruments and singing the real words to songs written by a very real musician. It’s the type of detail-oriented approach Wright is known for, but that doesn’t necessarily mean it’s easy. Michael Cera, Mark Webber, Alison Pill, and Johnny Simmons were given access to vocal, guitar, and drum teachers respectively before flying to Toronto to start rehearsals. Once there, they spent a solid month attending band practice in a communal rehearsal space. Sloan multi-instrumentalist Chris Murphy sat in as their guitar coach and each actor credits him as the invisible glue holding Sex Bob-Omb together. “He had a very good, supportive, loose energy and was super funny. It put you at ease immediately,” says Webber.

“My high-school self was freaking out because Sloan was a huge deal for me back then, but he actually made the whole experience super fun,” adds Pill.

However, the other reason they functioned so well as a fictional band is due to their history. Cera and Pill worked on sets together when they were young, and Pill knew Webber from a previous shoot years prior. “At that point, our collective comfort level was at full family, so we were just losing our minds like, ‘Man, this is the coolest!’ and gushing about how exciting it all was,” says Pill.

“I wish we were still a band so we could just hang out together. That’s the thing: It felt believable to us that we would all hang out, so why wouldn’t it feel believable that we would be in a casual band, too?” adds Cera. They were living within walking distance of one another in Toronto, meeting up for band practice each day, and grabbing meals together in the evenings. In many ways, Sex Bob-Omb was already a real band before shooting even began.

“All of us were self conscious about the actual playing. When you’re trying to look like a band, you don't want to look like you're trying to look like a band,” says Cera. “But then Alison showed up and she could play all of the songs already. It was very, very impressive. It was almost startling because it gave this great layer of credibility to the whole thing. She really made it look like she was the one leading the band, and she deserves all the credit for that.”

The real trick of Sex Bob-Omb coming to life was Mark Webber’s transformation into Stephen Stills. Webber had never picked up an instrument in his life, but was tasked with learning how to sing and play guitar at the same time. Despite practicing with two separate coaches for months, he quickly learned that his ability to tackle simultaneous parts dissolved when placed before the camera. So they improvised, focusing on Webber’s vocal lessons and tasking Chris Murphy with the close-up shots on Stills’ hands playing guitar instead.

“Thank god I didn’t have to portray a cool, successful musician because that would’ve been completely at odds with my genuine emotional state, which was borderline sheer terror and fear," Webber recalls. "The mantra in my head was constantly, ‘Don’t fuck this up, man.’” When Edgar was like ‘Yeah, we’re gonna use your voice [in the songs], Mark!’ I did a huge sigh of relief first that I didn’t screw it up before the actual excitement sank in way later.”

Webber still had to embody the frontman mindset though. As such, he and a few cast members occasionally chilled at local bars and hot spots to get a feel for the music scene vibe, often thanks to the guidance of Kevin Drew. “Kevin was like the mayor of Toronto,” says Webber. “He fucking knew everybody and people kept asking if we were brothers.” (Both Canning and Haines use that same title to describe him. “Kev is pretty much the mayor of Toronto, so we tend to leave the hosting to him,” says Haines. “He’s a pro.”)

To make the stress worse, they had to meet with Godrich to record their own vocals for the Sex Bob-Omb songs. Universal booked a professional recording studio for the occasion, but Godrich intuitively looked for a more intimate location to relieve some of the pressure from the actors. That’s how they ended up recording at Metric’s personal studio, an in-house setup hidden behind an “unassuming front door” off a main street. “It felt very important that it should be the actual actors recording their parts, and Jimmy [Shaw] from Metric let us use their studio to make it more casual,” says Godrich.

It was a once-in-a-lifetime scenario that was not lost on anyone, least of all Pill and Webber. Years earlier, while on a shoot in Germany, the two had a “whole experience” speeding down the Autobahn blasting "Sit Down. Stand Up." to go see Radiohead live. “Honestly, that whole experience was one of life’s great absurdities. ‘Oh, who’s producing our first album? Don't worry, it’s just Nigel Godrich?’ The saving grace was that we weren’t supposed to be that good,” says Pill. “But Nigel was very kind and just having fun because it was such an oddity for him. Thankfully, all I had to do was some background shouting. I got to enjoy the other side of it: 'Sure, let’s have a beer and get into it! Let’s yell!' Poor Mark had to do the heavy lifting.”

All of that emotional weight and nonstop work to emulate a fictional band paid off. In the movie, our introduction to Sex Bob-Omb is through a laid-back band rehearsal while Young Neil and Knives Chau watch from the living room sofa. While conversing, the musicians look bored and bothered, but once Pine screams her trademark introduction to the track, the three of them shift into high gear in synchronicity. As an elongated zoom stretches the screen -- created with a deceptive, 50-foot-long set piece -- and the opening title sequence floods the screen, the song swells louder and louder, barreling into haphazard whoops and a tempo too fast to stop.

A decade later, I vividly remember watching this scene in theaters and grinning wildly, my heart racing, a feeling I can only compare to being blown away by an unpromising opener at a show. “I remember in post-production seeing a first cut of that scene and knowing right away that this would pull people in,” says Bacall. “The song is so good, the perspective was awesome, and Knives’ reaction is perfect -- which is how you’re entering that world, through her eyes -- because it really did feel that magical to her.”

Once the Scott Pilgrim soundtrack came out, I bought it immediately and put it on regular rotation. It’s clear I wasn’t the only one. In addition to the soundtrack selling well upon release, it’s gone on to be streamed regularly over the past decade.Sex Bob-Omb’s music is particularly popular, with 11 million plays per song on Spotify, a streaming platform that wasn’t even available in the US until late 2011. When I read these numbers out loud, nearly every person laughs in disbelief. Pill is shocked; Bacall is incredulous that they once considered not even having the bands perform in the movie, only to have Scott Pilgrim develop it's own musical legacy. "Wait, all of their songs [have those numbers]? That’s funny to me," Godrich jokes. "It’s like, 'Hey, so where’s the second album at?'” Maybe it's not a second album, but just today Wright did announce re-releases of Godrich's score and the soundtrack, featuring a bunch of extra material.

It’s not just fans giving Sex Bob-Omb a belated standing ovation; it’s music critics, too. Ever since Scott Pilgrim’s release, Sex Bob-Omb are regularly ranked highly alongside fictional movie bands like the Blues Brothers, Spinal Tap, and the Cantina Band from Star Wars, with Rolling Stone dubbing them a “Le Tigre-meets-the-White-Stripes-meets-the-Buzzcocks power trio.”

“Wow, that’s amazing!” says Cera, laughing. “You know, my favorite band throughout my childhood was the Monkees. I didn’t care that they weren’t a real band. I remember playing the drums on my hamper when I was nine years old while listening to the Monkees on tape. I don’t think we had the same type of success as the Monkees in any way, but it’s pleasant all the same to know people still listen to us.”

"I’m not sure I was ever actually aware of any of this," Wright says, surprised and delighted. "Listen, a lot of the music that I was into when I was younger I got into through movies. I was the kid with the Blues Brothers album. I loved that album without having seen those Saturday Night Live sketches because we didn’t have that in the UK. I’m very happy to learn that the Sex Bob-Omb songs have millions of plays themselves. That’s amazing! I bet you Beck has no idea, too, which is hilarious."

In fact, Wright has a point: Maybe the devoted fascination with Scott Pilgrim and the longevity of its music is precisely related to the indie culture it was drawing upon. "In the last 30 years, the focus with a movie is that its opening weekend is the most important thing, that it’s the highest it will get," Wright explains. "You know, a film in the 21st century doesn’t have the same possibility to do what an album can do. But Scott Pilgrim was more akin to being an album. It was a niche thing being recommended by word of mouth, and I truly think that linked with the actual album is what helped it earn that cult status.”

The theme running through everything Scott Pilgrim -- the graphic novels, the feature film, the soundtrack, the video game that took on its own cultish status -- is a genuine love of music and pop culture, no matter who knows about it or how it ages. Everyone involved wound up creating a snapshot of an era in indie rock and culture without seemingly meaning to. The fact that it has persevered after all these years makes it all the more exceptional -- the final flourish of realistic magic in a world born from magical realism.