One morning in the summer of 2000, I woke up early, walked a mile to my nearest internet cafe, and spent half an hour hitting refresh on the Ticketmaster website. I had to be there when the tickets went on sale. Later that summer, the Beastie Boys and Rage Against The Machine were going to tour across the football stadiums of North America, and I had to make damn good and sure that I would be down on the field, in the thick of it, not up in the bleachers. This thing was going to be an event. These two bands had both come out of hardcore and rap music, and they'd kept their own sensibilities intact while becoming arena-wrecking rock-radio monsters. Even in the era of the nü metal that both bands had unwittingly helped to invent, they'd kept their credibility. I had to see it up close.

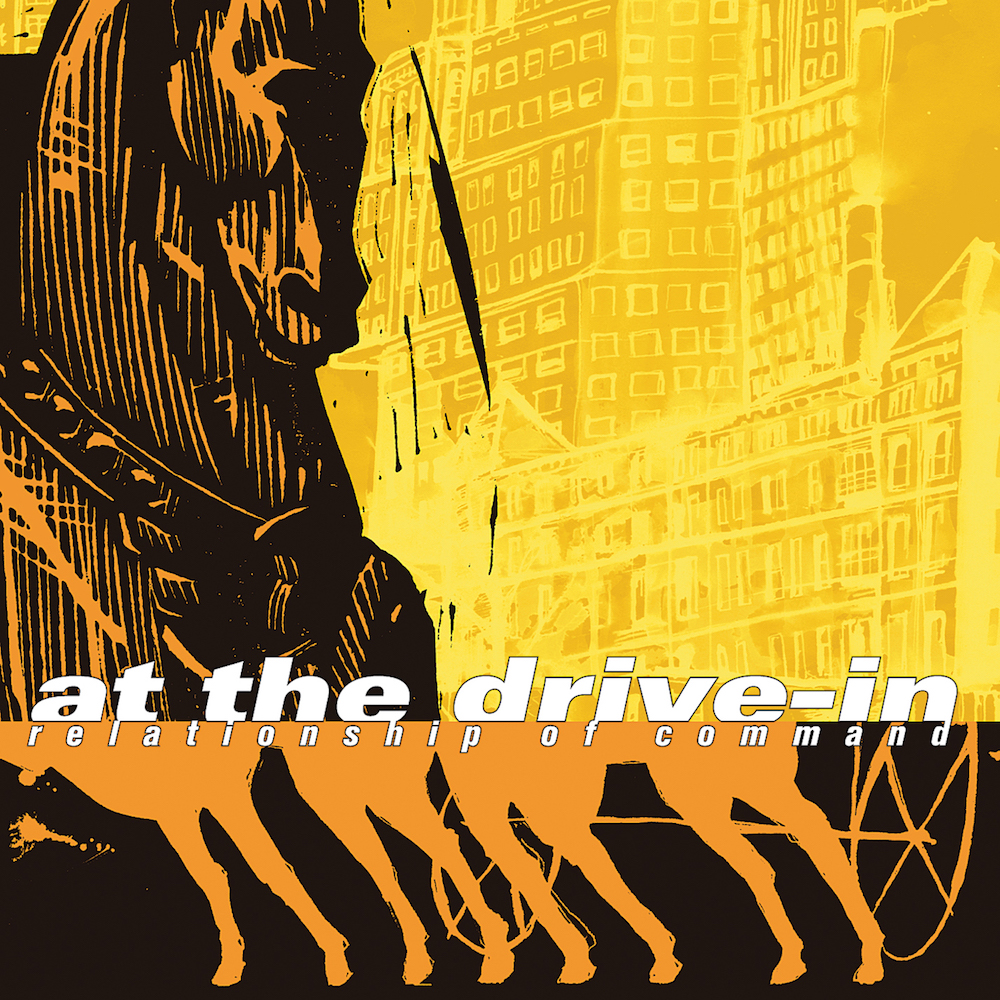

The opening acts were exciting, too. At least at the New York show, the Beasties and Rage were sharing the bill with Busta Rhymes and the Roots, possibly the two greatest live acts in all of rap music at the time. Also, at the bottom of the bill, set to play while people were still filing into the stadiums and finding their seats, were At The Drive-In, a Texan post-hardcore band who had already built serious mystique. At The Drive-In had already opened arena shows for Rage Against The Machine and Gang Starr, and they were getting ready to release their first major-label album on the Beasties' Grand Royal imprint. People were talking about their live shows in hushed, reverent tones. If anyone could make a half-empty stadium into someplace terrifying and exciting, it was this band. I could already see the whole thing in my head.

It didn't happen. A few weeks after I sat in that internet cafe, Mike D got into a mountain biking accident, fucking his shoulder up to the point that he needed surgery. The tour had to be postponed, and by the time it was ready to happen, Zack De La Rocha had left Rage Against The Machine. At The Drive-In played big festivals in Europe and Australia and Japan, but they never rocked the stadiums of their homeland. But then, we found out pretty quickly that this couldn't have happened.

At The Drive-In simply weren't equipped to play America's stadiums. They had the ability to do it. They would've destroyed. But the experience would've destroyed them, too. At The Drive-In were not built to handle adulation or even attention. If they'd played those stadium shows, they probably would've simply broken up a few months earlier than they already did. They might not have made it to the Relationship Of Command release date.

The annals of rock history are littered with bands who made their biggest and/or best albums and then immediately broke up: The Fugees, the Police, the Screaming Trees, the Verve, the J. Geils Band, Simon And Garfunkel, Girls. We could build a whole Hall Of Fame wing around these bands, and they we could argue about it for weeks: Do OutKast belong in there? Hole? Jane's Addiction? ABBA? Jawbreaker? If you start letting in bands that ended because somebody died, the list grows exponentially. Point is: Being in a band is a combustible situation. Being in a successful band is an especially combustible situation. And when you're in a band that's built around the idea of combustibility, you're living on borrowed time from day one. At The Drive-In were rock's answer to Eddie Guerrero, another transcendent and self-destructive Mexican-American artist from El Paso who took America's arenas by storm but who couldn't hold it together for long.

Post-hardcore, At The Drive-In's genre, is full of amazing bands that couldn't keep their shit together. Fugazi, At The Drive-In's heroes, managed to make it a full decade. But Fugazi were the exception, and even they only happened because Embrace and the Rites Of Spring had already run their course. Plenty of At The Drive-In's biggest inspirations and contemporaries suffered similar early ends: Drive Like Jehu, the Nation Of Ulysses, Slint, Antioch Arrow, Heroin, Deadguy, Botch. When At The Drive-In went on their headlining tour behind Relationship Of Command, their opening acts were the (International) Noise Conspiracy, who'd just formed out of the ashes of Refused, and the Murder City Devils, who were in the process of flaming out themselves. Historically, if you play frantically emotional and concussively angular guitar music, you don't do it for long.

At The Drive-In held it together for less than six months after the release of Relationship Of Command, an album that turns 20 tomorrow, before announcing an indefinite hiatus that would stretch out for a decade-plus before their underwhelming reunion. They had all sorts of reasons for splitting apart when they did: heroin problems, van crashes, onstage freakouts, internal tensions, fundamentally oppositional artistic goals. As the breakup faded further and further into the distance and more details came out, the whole history of At The Drive-In started to look different. They weren't symbols of lost hope and wasted potential anymore. Instead, At The Drive-In were Roman candles who flamed out gloriously in front of the world. And before they did, they left behind Relationship Of Command, an album that works as its own kind of miracle.

Relationship Of Command should frankly not exist. It's a product of contradictions and paradoxes, piled up on top of each other into a teetering tower. At The Drive-In may have been America's finest basement punk band, and yet they had ambitions that stand starkly at odds with the entire culture of basement punk, especially in the '90s. They were a predominantly Mexican-American group from a border town, coming out of Texas at the same time as their fellow Texan George W. Bush was getting ready to steal a presidential election. They signed to Grand Royal, a label dedicated to Beastie buddies who were largely content to play around in the Beasties' kitsch-culture sandbox, but they came out ripping with a sense of force and passion that even the Beasties hadn't shown in years. And they went to work with Ross Robinson, the producer whose work with Korn and Limp Bizkit was most responsible for turning late-'90s alterna-rock radio into an anti-human hellscape. That is a flammable combination of elements.

The best thing about Relationship Of Command is that you can hear that instability, that readiness to explode. Relationship Of Command is an album full of crazy, seesawing dynamics. There's no tension and release. Instead, the tension is the release. At The Drive-In were dealing with the same turn-of-the-millennium anxieties that Radiohead were putting into Kid A around the same time. But At The Drive-In weren't turning those anxieties into experimental architecture. Instead, they were screaming them out them with rabid intensity and muscular John Woo bullet-time grace.

Before Relationship Of Command, At The Drive-In had already put together a pretty serious discography on a shoestring budget, though the knock on their early records was always that they couldn't capture the intensity of their live show. Nothing could. But Relationship Of Command captures its own kind of intensity. Omar Rodríguez-López has always been vocal about how he hates the bright, crunchy loudness of the album's mix -- a mix that came from Andy Wallace, who'd already mixed Raising Hell and Reign In Blood and Nevermind and Rage Against The Machine and ...And Out Come The Wolves. Wallace does for At The Drive-In what he'd already done for Run-DMC and Slayer and Nirvana and Rage Against The Machine and Rancid. He brickwalls the fuck out of them and makes them sound huge.

That hugeness wouldn't suit most knife-edge post-hardcore bands, but it fits At The Drive-In beautifully. Even when Relationship Of Command slows down, when the band plays around with congas and pianos and effects-board mad-scientist rig-ups, they still sound like they've got lightning in their veins. The riffs are ugly and discordant and triumphant. The math-rock pyrotechnics somehow make the songs all the more anthemic. Cedric Bixler-Zavala's lyrics are mostly pure beatnik-poetry opacity -- "Dripping with drool from the nerves of this sentence" -- but he bleats them out with so much force that they become singalong standards anyway. At hardcore shows in Syracuse, soundmen would play "Arcarsenal" and "One-Armed Scissor" between bands, and kids would keep moshing. (At their own shows, At The Drive-In would demand that crowds refrain from moshing while throwing themselves violently around the stage and playing supremely mosh-ready music -- the ultimate self-defeating gesture for anyone who was not Fugazi.)

Iggy Pop appears on a couple of tracks from Relationship Of Command, and that's significant. Pop doesn't actually do much -- reading a half-surreal ransom note at the beginning of "Enfilade," adding some un-pinpointable backing vocals to the storm of "Rolex Propaganda." And yet Pop's participation is symbolic. Thanks to Bixler-Zavala and Rodríguez-López's towering Afros, rock critics already couldn't resist comparing At The Drive-In to the MC5. With Iggy Pop in there, the connection to the proto-punk bomb-throwers of late-'60s Detroit became concrete. It made sense to me. We needed our own bomb-throwers. After all, we had our own terrifying right-wing monster on his way into office, getting ready to launch his own pointlessly bloodthirsty imperial wars.

We didn't know that at the time. Neither did At The Drive-In. Even if they had known that, straight-up political anthems weren't their style. Bixler's whole thing was to scream cryptic word-puzzles with the sort of ferocity that made them sound anthemic: "This system is non-operational!" But if you're looking for prescient wisdom in Relationship Of Command, you'll find it. For obvious reasons, these days I keep getting stuck on this bit from "Quarantined": "Sanction this outbreak, a virus conspires/ Push becomes shove, days become months/ I seem to have forgotten the warmth of the sun." Those lines might've been metaphorical when Bixler-Zavala wrote them. They're not metaphorical anymore.

When the war machine kicked into gear, At The Drive-In had already been gone for years. They'd splintered into two different bands: the obfuscatory prog theatrics of the Mars Volta and the relatively generic oomph-rock of Sparta. I tried really hard to like the Mars Volta, and I didn't even really bother with Sparta. Either way, it pretty quickly became obvious that At The Drive-In were a special thing, greater than the sum of its parts. By the time the band finally got back together, that magic was gone.

And yet I can't be too sad about how things turned out. In the looming early-'00s era of detached whiskey-dick garage rock and cocked-eyebrow electro camp, At The Drive-In might've seemed overly intense -- the guy at the party who keeps talking about the pyramid on the dollar bill when everyone else just wants to roll that bill up and snort some lines. They got to skip all that, but not before they'd sold a million copies of arena-ready frag-grenade screaming-spazzout tantrum-rock to the kids in America. And if At The Drive-In were truly the emissaries of post-hardcore, it's only right that they should flame out like a post-hardcore band. There is poetry in refusing to be what the world wants you to become.