In The Number Ones, I'm reviewing every single #1 single in the history of the Billboard Hot 100, starting with the chart's beginning, in 1958, and working my way up into the present.

USA For Africa - "We Are The World"

HIT #1: April 13, 1985

STAYED AT #1: 4 weeks

Bob Dylan never has had a #1 hit. Dylan remains a pivotal cultural figure and a massively popular performer, and he's gotten to #2 a couple of times, with 1965's "Like A Rolling Stone" and 1966's "Rainy Day Woman # 12 & 35." ("Like A Rolling Stone" is a 10. "Rainy Day Woman" is a 6.) In 1965, the Byrds covered Dylan's "Mr. Tambourine Man" and took it to #1. But Dylan himself has never ascended to the top spot.

Bruce Springsteen has never had a #1 hit, either. Springsteen was one of the defining pop stars of the '80s, and he'll presumably be back to packing people into arenas as soon as it becomes both safe and culturally acceptable to pack people into arenas. Springsteen has a ton of top-10 singles, and he's gotten to #2 once, with 1984's "Dancing In The Dark." (It's an 8.) In 1977, Manfred Mann's Earth Band covered Springsteen's "Blinded By The Light" and took it to #1. But Springsteen himself has never ascended to the top spot.

And yet Bob Dylan and Bruce Springsteen have both appeared on a #1 single -- the same #1 single. The two of them are responsible for what may be the two silliest moments on "We Are The World," the noisy and self-congratulatory all-star singalong that became a cultural event in 1985. Dylan and Springsteen don't make a ton of musical sense on "We Are The World." Dylan sounds like a frog dying. Springsteen sounds like an angry man shitting out a pinecone. And yet they're both there, both lending whatever gravitas they can muster to this ridiculous enterprise.

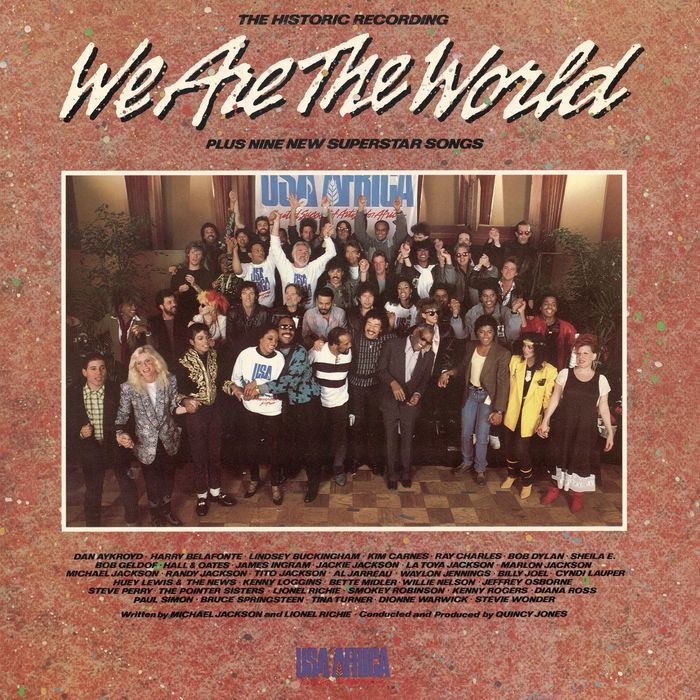

Lots of people are on "We Are The World." This abundance is the prime selling point of the product -- that and whatever guilt relief that record buyers earned when they spent a few bucks on a puffed-up and solemn seven-minute nothing of a song. The cast of characters on "We Are The World," all of whom assembled into a single recording studio on a single Los Angeles night, is vast and impressive. The backup-singer chorus on "We Are The World" -- the teeming mass of singers who don't even get a chance to sing a solo line -- features big stars like Smokey Robinson and Bette Midler and Lindsey Buckingham. The soloists are a parade of most of the biggest names of the day. There was so much talent in that room, and yet it's all there to make a tranquilizing musical irritant. I'll never understand it.

The British had the idea first. In 1984, the Boomtown Rats' Bob Geldof and Ultravox's Midge Ure put together a big supergroup of mostly-British singers, and they recorded "Do They Know It's Christmas?," an ooky but well-meaning holiday synthpop ditty. ("Do They Know It's Christmas?" seems to imply that the hard thing about being African is that there's no snow? And that without snow, nobody will know it's Christmas? Weird song.) The single, released under the name Band Aid to raise money for Ethiopian famine relief, sold three million copies in the UK alone. For years, it was the biggest-selling single in UK history. (In the US, it peaked at #13.)

Around the same time, the entertainment-industry legend Harry Belafonte wanted to put together a big benefit concert for famine relief. (Belafonte has never had a single on the Hot 100, but he was at his peak in the years before Billboard started this list. Belafonte's Calypso, for instance, was the biggest-selling album of 1956, the first year that Billboard kept track of those things.) A couple of days before Christmas 1984, Belafonte called up the high-powered manager Ken Kragen, who suggested that they try instead to come up with an all-star single like "Do They Know It's Christmas?"

Kragen lined up his clients Kenny Rogers and Lionel Richie first, and he got Quincy Jones to agree to produce it. Richie recruited Stevie Wonder, suggesting that the two of them write it together. Jones asked Michael Jackson if he'd do the song, and Jackson said that he wanted to sing on it and help write it. So Richie and Jackson got together at Jackson's family's house in Encino to write the song. (Wonder was busy.) Jackson and Richie spent a week trying to make the song as simple and memorable as possible, and then Jackson surprised both Richie and Quincy Jones with a demo for the track that he'd recorded in a single night.

https://youtube.com/watch?v=S0jgkb5mgw8

Jackson and Richie finalized the "We Are The World" lyrics on the night before the recording session. They changed "we're taking our own lives" to "we're saving our own lives" so that it wouldn't sound like they were talking about suicide. They changed "there's a chance we're taking" to "there's a choice we're making" so that they wouldn't sound so egotistical.

Meanwhile, Kragen worked his way down the Hot 100, calling everyone he could find and trying to get them to agree to the project. Kragen had the idea to record the song on the same night as the American Music Awards, which were going down in Los Angeles at the end of January. That meant that a ton of stars would be in town that night, but it also meant that Kragen only had a month to get the deal done. Kragen ended up doing too well at recruiting stars; he turned away fading names like John Denver.

Kragen's two white whales were Bruce Springsteen and Prince. After Kragen badgered Springsteen's manager into it, Springsteen was down. Prince, on the other hand, thought that the whole thing was wack. He couldn't see how his voice would work in that all-star cacophany. This wasn't the way Prince operated. Sheila E., Prince's friend and collaborator, had agreed to sing in the chorus, and she did her best to get Prince to show up. But Prince went out partying in LA that night instead. Quincy Jones had planned on Prince participating. When Prince no-showed, Huey Lewis, who'd originally been set to sing in the chorus, got bumped up to soloist.

When the stars arrived at the studio that night, they were famously met by a sign that told them to check their egos at the door. Quincy Jones may have been the only producer tough enough to keep everyone in line. Jones mapped out beforehand who would get to sing which lines and taped those lines to mic stands, and he didn't allow for any arguments over who would sing what. In his notorious 2018 Vulture interview, Jones told a story about how Cyndi Lauper tried to start some kind of rebellion:

She had a manager come over to me and say, “The rockers don’t like the song.” I know how that shit works. We went to see Springsteen, Hall & Oates, Billy Joel, and all those cats and they said, “We love the song.” So I said [to Lauper], “OK, you can just get your shit over with and leave.” And she was fucking up every take because her necklace or bracelet was rattling in the microphone. It was just her that had a problem.

There are other fun stories from the night of the session. There's Michael Jackson hiding in the bathroom. There's Stevie Wonder joking that he and Ray Charles would drive everyone home if it took too long. There's Wonder suggesting that everyone replace the nonsense syllables at the end of the song with some words in Swahili, and then there's Waylon Jennings flat-out refusing to sing in Swahili. (They went with "one world, our children" instead.) There's Billy Joel getting starstruck at seeing Ray Charles, and then Bob Dylan silently snubbing a gushing Al Jarreau, leaving Jarreau sobbing. (A lot of those stories are in this great Independent feature.)

Because I'm a hopeless completist doofus about things like this: Al Jarreau is one of only five soloists on "We Are The World" who never scored a #1 single of his own. Jarreau, in fact, never had a top-10 hit. His highest-charting single is 1981's "We're In This Love Together," which peaked at #15. Willie Nelson's two highest-charting singles, 1982's "Always On My Mind" and the 1984 Julio Iglesias duet "To All The Girls I've Loved Before," both peaked at #5. ("Always On My Mind" is a 10. "To All The Girls I've Loved Before" is a 5.) As the frontman of Journey, Steve Perry's highest-charting single is 1982's "Open Arms," which peaked at #2. (It's a 7.) As a solo artist, Perry's highest-charting single is 1984's "Oh Sherrie," which peaked at #3. (It's another 7.) We've already been over Bob Dylan and Bruce Springsteen.

It's fun to think about all these people getting together in the same room for the same all-night session, to imagine all the weird conversations that people must've had. It's fun to think about Harry Belafonte in the chorus, beholding what he'd wrought while standing next to Dan Aykroyd, also in the chorus for some mysterious reason. It's fun to see the weird little harmonizing pairs: Paul Simon and Kenny Rogers, Willie Nelson and Dionne Warwick. But it's not any fucking fun at all to listen to "We Are The World."

"We Are The World" is a tough hang. It's a glacial and unending seven-minute ordeal, an ongoing series of stars stepping up to deliver their most anguished and worried wails. Most of them only get a sentence or less, so they put everything they have into singing hot-air platitudes: "It's time to lend a hand to life, the greatest gift of all."

The backing-band musicians on "We Are The World" are mostly the same ones who played on Michael Jackson's Thriller -- including Toto's David Paich, a past chart-topper himself. And yet they bring none of the hard, rippling excitement that you can hear on Thriller. Instead, "We Are The World" is pure musical goo, a shiny rhythmless trudge that's only there to melt into the background. The focus, instead, is on the singers.

Some of those singers sound pretty great. Whatever her feelings on the song, Lauper howls the absolute fuck out of her one big line, and Jackson himself is sensitively shivery on his solo moment. Some of them, like Dylan and Springsteen, sound like butt. Mostly, though, they're just a mismatched mass, a big group of people who don't have any chemistry with one another and who aren't entirely certain why they're all there. The song is a chore, and it sounds like one.

"We Are The World" is a song created with the best of intentions in mind. And it did its job. The single sold more than 20 million copies, and it topped charts around the world. There was a companion-piece album, too, and that also sold a few million. (Prince might not have participated in "We Are The World" itself, but he did donate the song "4 The Tears In Your Eyes" to the album.) There were shirts and videocassettes and various other commodities, and the whole thing brought in more than $60 million. And at least as far as I can tell, it looks like most of that money actually went to improve the lives of impoverished people -- never a given when it comes to all-star charity affairs like these.

So "We Are The World" accomplished its goals. It did good in the world. USA For Africa is still an operational charity, and it still uses the proceeds from the song to help people. I'm glad. But I hate the song. I hate it so fucking much. Part of it is the song itself -- a piece of music that's both oppressively boring and catchy enough that it continues to oppressively bore me even when I'm not actively listening. But part of it is the self-indulgent nature of the whole enterprise.

I simply don't get the idea of an initiative like this. If the artists involved in "We Are The World" -- or, better yet, their record-label bosses -- had donated a couple of percentage points of their annual income around that time, they probably would've generated even more money. But that's not the way we do things. Instead, we make a whole spectacle out of any sort of humanitarian action, turning what could've been a simple fundraiser into a giant glittering moment. It grosses me out every time something like this happens.

Maybe we should judge "We Are The World" by what it did -- as a collective work of humanitarian empathy, not as a piece of music or a spectacle. As a spectacle, though, it's an uncomfortably showy display. And as a piece of music, it sucks shit.

"We Are The World" went on to win Grammys for both Record and Song Of The Year, and it pulled in trophies at all the other big awards shows too. And then there were copycats. In 1986, Ken Kragen tried to corral more big stars into raising money to combat American homelessness with the Hands Across America event, but the big stars didn't really turn out, and the theme song peaked at #65. A bunch of Canadians -- Neil Young, Bryan Adams, Joni Mitchell, John Candy -- came together under the name Northern Lights for a song called "Tears Are Not Enough" than ended up on the We Are The World album. Ronnie James Dio led a crew of metal types on "Stars," a 1986 song credited to Hear 'N Aid. Eventually, that same impulse led to all-star rap posse cuts like 1989's "Self Destruction" and 1990's "We're All In The Same Gang."

My favorite of those all-star charity songs, both aesthetically and philosophically, is "Sun City," the 1985 song written and organized by the E Street Band's Steven Van Zandt. The song protested against South African apartheid, and it made a rallying cry out of refusing to play the South African resort that sometimes booked big stars. "Sun City" had Springsteen and Run-DMC and Joey Ramone and Gil Scott-Heron and Jimmy Cliff and Melle Mel and Bob Dylan and Bono and Bobby Womack and Bonnie Raitt and a lot of other people. Cool lineup! Pretty good song! But compared to "We Are The World," "Sun City" was a flop, peaking at #38. (On the other hand, African poverty still exists, but South African apartheid doesn't. So maybe "Sun City" was more successful.)

In 2010, a whole mess of newer superstars came together to raise money for the people of Haiti after the devastating earthquake there. They assembled at the same studio for a new version of "We Are The World," and it was even longer and possibly even more uncomfortable. Crash auteur Paul Haggis directed the video. There was rapping. This new "We Are The World" was, if possible, even more of a well-intentioned mess than the original. "We Are The World 25 For Haiti" peaked at #2. (It's a 1.)

This year, Lionel Richie talked about doing another version of "We Are The World" for COVID-19 relief. It hasn't happened, but it did inspire me to write this dumb shit. Unless that version of "We Are The World" comes out -- or some other version of the song happens for some other reason -- then USA For Africa won't be in this column again. But Michael Jackson, Lionel Richie, Stevie Wonder, James Ingram, Billy Joel, Dionne Warwick, Huey Lewis, Cyndi Lauper, and Bette Midler all will.

BONUS BEATS: Here's the absolutely savage "We Are The World" parody that In Living Color aired in 1992:

(Jamie Foxx, who plays Lionel Richie in the In Living Color sketch and who would later act as the concerned presenter of the "We Are The World 25 For Haiti" video, will eventually appear in this column as a guest. As lead artist, Jamie Foxx's highest-charting single is the 2009 T-Pain collab "Blame It," which peaked at #2. It's an 8.)

BONUS BONUS BEATS: Here's Master P starting out his 1992 track "Psycho Rhymes" with a "We Are The World" parody:

(Master P's two highest-charting singles as lead artist, 1998's "I Got The Hook Up!" and "Make 'Em Say Uhh!," both peaked at #16. As a guest-rapper, P's highest-charting single is Montell Jordan's "Let's Ride," which peaked at #2 in 1998. It's a 7.)

BONUS BONUS BONUS BEATS: Apparently, 1992 is the year that the world finally turned on "We Are The World." Here's the classic riff on the whole celebrity-singalong industrial complex that was part of a great 1992 Simpsons episode:

(As a solo artist, Sting will eventually appear in this column.)

BONUS BONUS BONUS BONUS BEATS: Here's Mitch Hedberg using "We Are The World" in a classic stand-up bit on his 2003 album Strategic Grill Locations:

BONUS BONUS BONUS BONUS BONUS BEATS: Here's Jimmy Kimmel working a "We Are The World" parody into his viral 2009 bit "Fucking Ben Affleck":

(I'm not going to get into the highest-charting single of every single motherfucker on "Fucking Ben Affleck," but Huey Lewis and Meat Loaf will eventually appear in this column. As a member of *NSYNC, Lance Bass will be in here, too.)

THE 10S: Bruce Springsteen's painfully horny synth-rockabilly slow-burn "I'm On Fire" peaked at #6 behind "We Are The World." It cut a six-inch valley through the middle of my skull, and it's a 10.