It’s a crudely animated video in the tradition of eBaum's World hits like "End Of Ze World" and "Sensimilla Street," which range from cheekily irreverent to so offensive Matt Stone and Trey Parker would blush. Likenesses of Southern rappers Soulja Boy, OJ Da Juiceman, Gucci Mane, and Waka Flocka Flame deliver self-deprecating verses that highlight their respective shortcomings as rappers, from Soulja’s mindlessly repetitive hook to Gucci’s slurry Boomhauer-isms. The one-note joke is best summed up by faux-Gucci's couplet, "Ride the short bus to class/ I made a 'Z' on my report card, so I passed." Here, we see distinctly 2000s brands of comedy and hip-hop criticism simultaneously issuing their last gasps in the first year of the new decade. This is "Shawt Bus Shawty," a parodic 2010 music video that currently sits at just under 49 million views. (I’d embed it below, but I don’t think anything this disrespectful to the intellectually disabled deserves more than a hyperlink.)

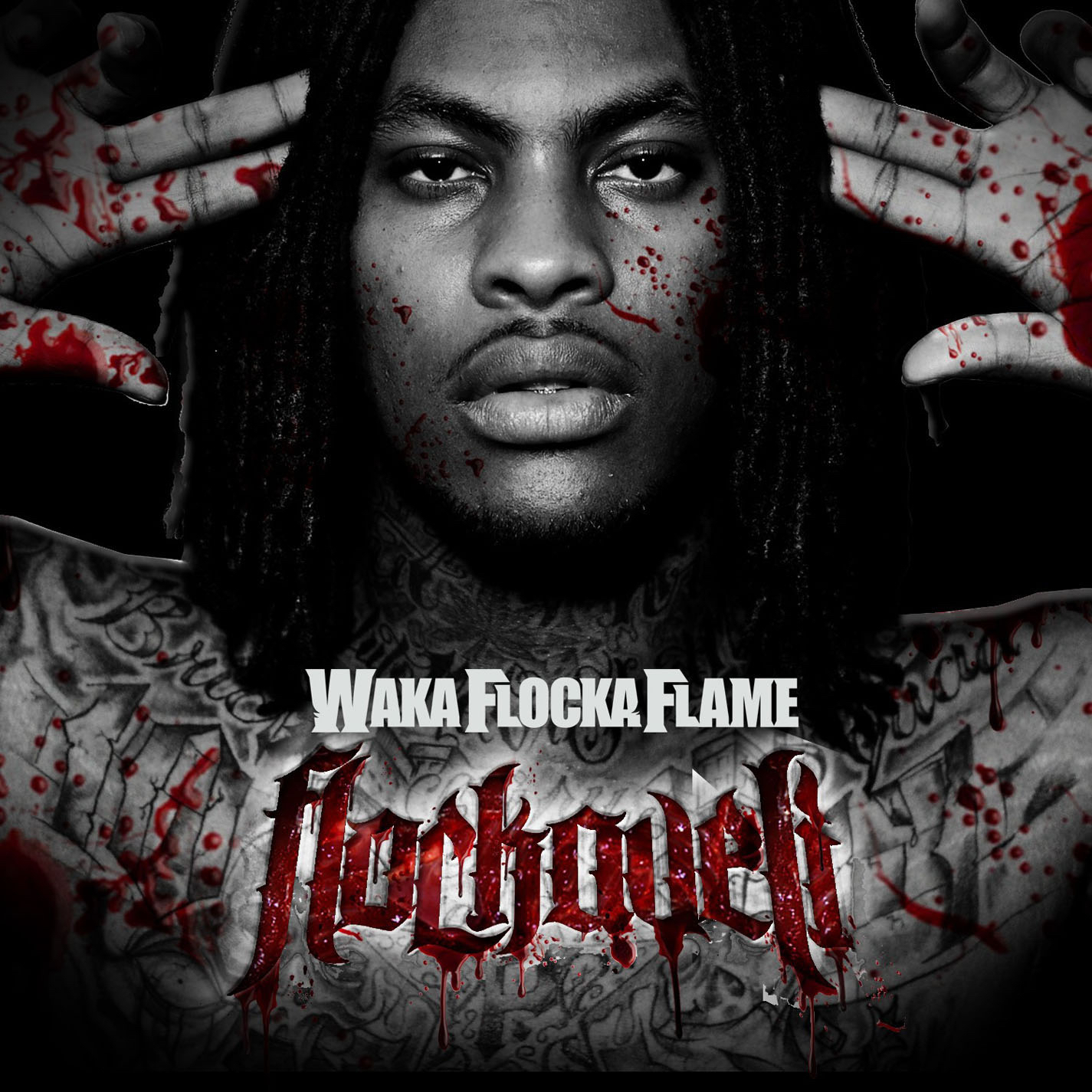

Why, on the national-holiday-worthy 10th anniversary of Waka Flocka Flame’s Flockaveli, of all days, am I bringing up a juvenile relic that deserves to stay buried under stifling layers of cultural sediment? Because needlessly derogatory as it may be, "Shawt Bus Shawty" reflects a sentiment that stretched far beyond edgelords with rudimentary understandings of Macromedia Flash. For a wide slice of the rap-listening population, Waka Flocka's debut album made him Public Enemy Number One.

[videoembed size="full_width" alignment="center"]https://youtube.com/watch?v=JaoX2SpVEkM[/videoembed]

To illustrate, let’s leave cultural criticism’s South Pole (animated YouTube parodies) and journey way up north, close to its highbrow terminus. A few months after Flockaveli, longtime rap radio fixture Jay Smooth dubbed Waka the "leader of hip hop's Tea Party movement" in a segment on NPR's All Things Considered. Smooth's metaphor of choice (politics) is much classier than "Shawt Bus Shawty"'s, but both critiques boil down to the same general point: "verbal dexterity and lyrical complexity," to borrow Smooth’s words, are hip hop’s paramount values, and Waka represents the genre's nadir. (Also worth noting: The only other "anti-musical, anti-intellectual" rappers Smooth cites alongside Waka are his three "Shawt Bus Shawty" co-stars.) Feigning an unbiased perspective, Smooth pits Waka's detractors and fans against each other, describing what each side sees in the bellowing Atlanta rapper. Judging by his timely Tea Party comparison, though, it's clear which side Smooth was on:

A movement fueled only by catharsis can be hard to sustain in the long-term, and you might well question whether Waka Flocka Flame or the Tea Party will still be viable around 2012. But for the moment it shouldn't be hard to understand the allure of the untutored outsider that's made Waka Flocka Flame such a big hit. Those Americans who can't align themselves with the Tea Party might even want to try Waka Flocka Flame, as an alternative way to shout their stresses away.

Smooth was right -- neither the Tea Party nor Waka maintained long-term relevancy -- but their respective downfalls were self-inflicted, and they both sowed seeds that continue to impact us a decade later. For now though, let's set aside this flimsy metaphor and actually talk about why Flockaveli was game-changing enough to incite so much backlash.

[videoembed size="full_width" alignment="center"]https://youtube.com/watch?v=TP84QdaAHZU[/videoembed]

Waka had only been rapping for a couple of years before his mixtape cut "O Let's Do It" became a regional hit. He initially got his foot in the door when he was introduced to future collaborator and label boss Gucci Mane by his mother, Debra Antney, who managed Gucci for several years beginning in the mid-2000s. During those early days, the 6'4" Waka also served as Gucci's muscle, which Gucci often alluded to in his music (see 2006's "Zone 6": "Got a tall n**** with me but he can't really hoop/ But they call him Kobe Bryant cuz they know he gon' shoot"). "He was not a rapper," Gucci wrote of 19-year-old Waka in his 2017 autobiography, going on to describe the "crazy, wild, stupid shit" that the teenager and his friends engaged in at the time.

Atlanta-based producer Southside was one of those friends. When I interviewed him in 2015, he recalled himself and Waka going to the club "40 deep and beat[ing] the whole security team up" as adolescents. Fast forward a few years to when Flocka brought "O Let's Do It" to the same club: "We went to the club 80 deep, so if 80 people in the club moving to this song, what is the rest of the club gonna do? Jump around and be wild the same way." It's a great illustration of Waka's infectious on-record energy -- he incites the same rowdy behavior he himself was known for, minus the need to throw punches. "Club goin’ stupid when I 'O Let’s Do It,'" as he puts it on another Flockaveli track.

Keeping in mind spiritual predecessors like Three 6 Mafia and Lil Jon, music to fuck the club up to was already a well-established lane by the time Waka started rapping, and while "O Let’s Do It" surely belongs in that canon, he needed an additional jolt to reach Flockaveli's signature sound. That came in the form of Lex Luger, a Virginia-based producer who cold-emailed Waka then started sending him beats via Myspace. When Flocka rapped, "Lex Luger on the track, that's good for my health," on his April 2010 mixtape LeBron Flocka James 2, they already had a slew of collaborations on the books, but he can’t have known just how true those words would prove. One month later, he released a properly mastered version of Luger-produced mixtape track "Hard In Da Paint" as his second single, and the Earth promptly exploded.

[videoembed size="full_width" alignment="center"]https://youtube.com/watch?v=3rFpYrrhJpQ[/videoembed]

OK, that’s an exaggeration, but so is "Hard In Da Paint." The song’s individual elements -- menacing synth-brass, triplet-heavy percussion, top-of-the-lungs yelling, an ad-lib track just as active as the lead vocals -- all existed, in some form or another, in pre-2010 street rap, namely Gangsta Grillz tapes like Jeezy’s 2006 monster Streets Iz Watchin. But when combined into a no-holds-barred Royal Rumble, the result is absolutely jarring, a maxed-stats video game character running over everything in its path. I remember hating it the first time I heard it. As a 19-year-old more interested in Kanye and MF Doom, my opinion was aligned with Jay Smooth’s, and there I was laughing my hateful ass off at “Shawt Bus Shawty.” But soon enough I was blasting “Hard In Da Paint” so loud that the first bass drop blew a pair of my friend’s speakers (I’m still so sorry, dude). Flockaveli was just so infectious that I couldn’t ignore it.

Both LeBron Flocka James tapes that preceded Waka’s commercial debut are excellent, but Flockaveli boiled down Lex Luger’s formula to perfection and went straight for the jugular. Luger (who produced over half of the album) paints an end-of-days fresco, taking the gothic sounds of predecessors like Drumma Boy and Shawty Redd to their logical extremes and outfitting them with skittering drum patterns that whip by like machine gun fire through the jungle in a Vietnam movie. Waka could not have found a better complement to his rapping style, a freestyle-heavy approach that prioritized rawness over dazzlement. There’s a scene in Casino Royale where the guy James Bond is chasing acrobatically swings through a tiny gap in a wall, and instead of doing the same, Bond simply runs straight through the wall. That’s Flocka in a nutshell.

Those are the eye-catching, world-conquering aspects of Flockaveli, but letting them define the album as some kind of dead-eyed monster movie titan is exactly where the naysayers went wrong. Aggression often masks Waka’s heart, but that makes it all the more powerful when he wrenches it out of his chest. Despite cloaking itself as a middle finger to everyone else, “Fuck This Industry” is just as much (if not more) of an outpouring of thanks to Waka’s friends and family. He hurls threats left and right on “Hard In Da Paint,” but then Luger cuts the beat out and he drops a plainly-stated bomb: “When my little brother died I said, ‘Fuck school.’” That’s just as powerful as any one line Kendrick Lamar’s ever written.

But let’s be real: Flockaveli’s main strength is the fact that it strips away nearly everything that had softened bygone candidates for Hardest Rap Album/Tape Ever — melodic choruses, recognizable samples, outdated beats, huge guest stars, etc. The one exception is the chipper radio hit “No Hands,” and if it wasn’t the platonic ideal of a strip club anthem, it’d be a problem.

[videoembed size="full_width" alignment="center"]https://youtube.com/watch?v=4SPqzC6RkbQ[/videoembed]

Sure, even aside from that surprisingly refreshing, coherence-interrupting hiccup, there’s filler. There are about 20 too many guest verses, the lurid lowlights of that superfluous bunch being Baby Bomb’s on “TTG,” which literally just consists of him saying “I’m Baby Bomb” 10 times, and Uncle Murda’s on “Live By the Gun,” in which he outs himself as so homophobic that he relished Omar’s death on The Wire (who could hate Omar?!). All but one of the 19 songs are over three minutes long; none of them should be. But maybe I like Flockaveli better the way it is. Waka and Luger are so chaotic unto themselves that anything but an absolutely chaotic album would feel overly manicured.

Flockaveli’s immediate impact on hip hop was powerful but short-lived. Luger’s sound was in-demand for about one year — during which Rick Ross, Kanye, Juicy J, DJ Khaled, and dozens of others blew up his phone — before he was overtaken by a new school of trap producers whom he directly influenced. Waka’s personal vibe was tougher to replicate, and despite paving the way for some similarly hard-nosed drill rappers, he fell out of fashion just as quickly as Luger, even as he continued to make bank on the EDM festival circuit.

The more lasting aftershock of the album, I think, is felt in conversations around hip-hop, rather than the actual music itself. The intellectual superiority card that “Shawt Bus Shawty” and Jay Smooth played has, outside of J. Cole memes, largely gone out of fashion, especially among professional rap critics. There will always be Eminem diehards (or Joyner Lucas diehards, or Logic diehards) who won’t take anybody seriously unless they’re rapping at a million miles a minute, but it feels like Flockaveli was a real turning point towards judging hip hop the way people judge every single other genre of music. Not every folk songwriter aspires to be Bob Dylan; not every rapper aspires to be André 3000. There’s space in punk for the Ramones’ nursery rhyme writing; there’s space in hip hop for “Gucci Gang.”

But this otherwise happy ending has an unfortunate footnote: Waka actually began listening to his critics. Back in the LeBron Flocka James 2 days, he openly mocked them, rapping, “They call me Flocka, I ain’t got no lyrics.” By 2014, he seemed to take it more personally, titling a mixtape I Can't Rap, lowering his voice, and trying out faster, more traditional flows. Then earlier this year, completely disowned the Flockaveli era: “I was a wack rapper.” That one hurt. Regardless of his assessment of his own abilities, I hope Flocka someday realizes how Flockaveli brought the world to its knees and changed hip hop for the better.