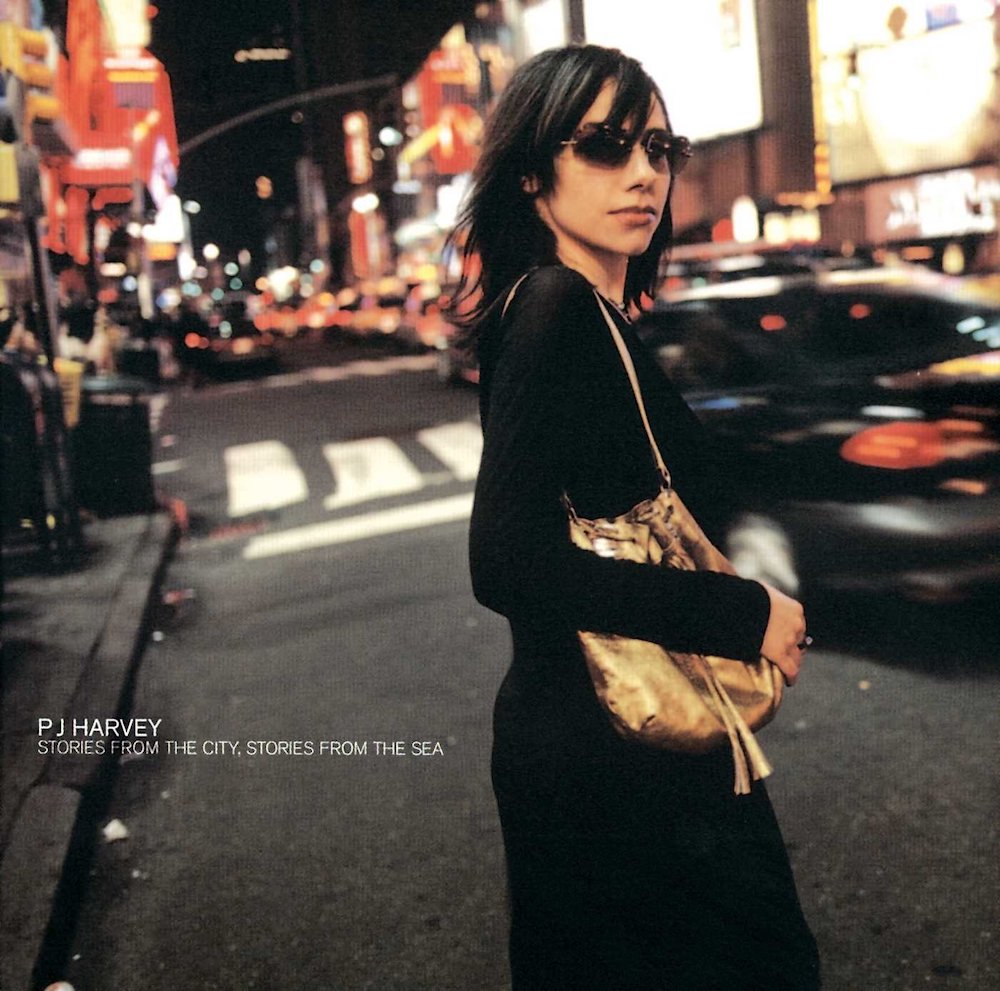

The general-consensus narrative around PJ Harvey's Stories From The City, Stories From The Sea goes something like this: It's PJ Harvey's happy album. Harvey recorded Stories From The City after spending months in New York in some kind of mad, euphoric relationship. (Harvey keeps her personal life quiet, but the rumor has always been that the dizziest love songs on Stories From The City are about Vincent Gallo.) To that point, Harvey had built a career by mining human darkness and obsession, making clangorous noise-rock and haunted blues. With Stories From The City, she went a different direction, making pretty and glamorous and cleaned-up modern rock music that pulled people in rather than pushing them away. She wound up with one of her biggest and most acclaimed albums. But with Stories From The City, Stories From The Sea turning 20 tomorrow, it's worth asking whether the album really is a ray of sunshine. Short answer: Nope!

PJ Harvey's music tends to resist easy narratives like that. It always has. When Harvey first rose up from the English countryside, she didn't fit into any neatly defined scene or movement. She sang stark and angry songs that laid bare the desperation often involved in the imbalances of gender politics, but she wasn't exactly making empowerment anthems. She worked with Steve Albini around the same time that Nirvana did, but her music had nothing to do with the grunge zeitgeist. She flirted with alt-rock radio stardom with 1995's To Bring You My Love, a virtuoso album of gothic-romantic druid-blues hymns, but this just led to weird spectacles like the time I saw her shimmying around onstage at a radio-station festival in a DC football stadium -- wearing a sparkly red ball gown in full daylight and trying to figure out what to do with the beach ball that someone had just tossed onstage.

The truth is that Polly Jean Harvey never made any sense when kicked into anyone else's cultural narrative. She was always a singular voice, and her context was her own. Stories From The City, Stories From The Sea was Harvey's fifth proper album, and it came two years after Is This Desire?, an LP of icy soundscapes and doomed-romantic poetry. Stories From The City is really only a bright album in comparison to that. By any other metric, though, Stories From The City is still heavy, pointed, merciless music. It's still, in other words, a PJ Harvey album.

Consider: How many crazy-in-love records open with their protagonists wailing about oncoming danger? The New York of Stories From The City isn't exactly a glamorous playground, and "Big Exit," the album's first song, is all about the grinding stress of trying to find a place in a violent, gun-happy culture that is not your own: "I want a pistol in my hand/ And I want to go to a distant land." Elsewhere, on a song called "The Whores Hustle And The Hustlers Whore," Harvey looks around her and feels nothing that looks anything like hope: "Speak to me of heroin and speed/ Of genocide and suicide, of syphilis and greed." She sounds an awful lot like someone who's been dating Vincent Gallo.

Around the time Stories From The City came out, Harvey told Q that she was trying to make "absolute beauty": "I want this album to sing and fly and be full of reverb and lush layers of melody. I want it to be my beautiful, sumptuous, lovely piece of work." There's a swirling urgency to Stories From The City, a hard-driving grandeur. Co-producing alongside her bandmates Rob Ellis and Mick Harvey (no relation), Harvey recorded Stories From The City at a 17th-century English mansion that she'd converted into a studio -- a flex. She also brought Thom Yorke in to sing on three songs, with her album coming just weeks after Radiohead released Kid A -- another flex. But for all its swagger, Stories From The City still sounds raw and feverish and uncomfortable. It only rarely sounds happy.

Consider "This Mess We're In," the track where Harvey gives up lead-vocal duties to Yorke. Yorke's presence feels like an event. Around the same time he was leaving behind guitar rock for splintered-soundscape exploration, Thom Yorke lets his unearthly tenor float over the sort of fuzzy churn that sounds straight out of The Bends. Harvey has Yorke singing some words that sound frankly hilarious coming from him: "Night and day, I dream of making love to you now, baby." Harvey answers him back in icy little ripostes, as guitars and pianos surge an whirl around them, building a tension that the song never releases. By the end, Yorke is wailing wordlessly through a seething storm. He sounds like a man trying to hold on in a hurricane, not like someone who's dreaming of making love with you now, baby.

There are moments on Stories From The City where Harvey does sound truly happy. "You Said Something" captures a moment of glorious connection. Harvey depicts herself on a Brooklyn rooftop late at night -- a truly romantic place in almost any context -- and tells a story about a moment that immediately etched itself on her mind: "I see five bridges/ The Empire State Building/ And you said something that I've never forgotten." She never tells us what this person said. She just lets us know that it meant something. Elsewhere, she invokes the L-word like it's some kind of talisman: "This is love, this is love that I'm feeling."

More often, though, Harvey just sounds horny. Harvey had been singing about sex since she first appeared on the scene. Sometimes, sex was oppressive. Sometimes, it was a source of weaponized power. Stories From The City is the one Harvey album where sex just sounds like a fun thing to do: "I can't believe life's so complex/ When I just wanna sit here and watch you undress." There's a flirty growl in her elemental howl, and there's some panting in the guttural trudge of her band. From time to time, she sounds like she's enjoying herself. That's not quite the same thing as dizzy joy, but it's something.

For all its playfulness, though, Stories From The City, Stories From The Sea is not, by any means, a pop album. The music has absolutely nothing to do with what was happening in alt-rock in 2000. Harvey might've been in New York just as Brooklyn was beginning to establish itself as a cool place to be, but there's no Strokesiness in the album. There's no rap-metal tick-tick-boom, either. Thom Yorke might be there, but Harvey isn't going for Radiohead-style architectural dread. She's ultimately only in conversation with herself.

PJ Harvey, as it happens, first moved to New York around the same time I did. I was in love, too. I had some transformative moments on Brooklyn rooftops, too. I spent the summer of 2000 living with my first serious girlfriend and a couple of friends -- four of us piled on top of each other in a two-bedroom railroad apartment on the Park Slope/Sunset Park border. As soon as the summer was over, I went back to college, and we broke up. Then, a couple of months later, Harvey released Stories From The City, and she sang about a lot of the same soul-flying feelings and deadening anxieties and tactile sensations that I'd just been going through. To me, the album became a requiem for a moment -- a weirdly comforting snapshot of an experience that had already come to a definitive end.

I wonder how many other people heard something similar in Stories From The City, especially as time went on. Stories From The City wasn't a hit in any conventional way, but it sold. Worldwide, the album moved about a million copies -- roughly the same number that To Bring You My Love had done five years earlier. But To Bring You My Love had alt-rock radio airplay and 120 Minutes rotation working for it. That didn't happen with Stories From The City, at least in the US. (In the UK, where the album went platinum, all three singles from Stories From The City just barely missed the top 40.)

Instead, Stories From The City found its audience through mainstream critical love, like Robert Christgau's Rolling Stone rave. (Snotty young Pitchfork was more suspicious.) The album earned Harvey two Grammy nominations -- in the rock category, not in the nebulous "alternative" zone. She lost to U2 and to Lucinda Williams, but that's still pretty good company. (Stories From The City and Linkin Park's Hybrid Theory, two albums that came out on the same day, both lost Best Rock Album to U2. These are the only things that Stories From The City and Hybrid Theory have in common.) More importantly, Stories From The City won the UK's Mercury Prize, beating out huge albums from Radiohead and Basement Jaxx and Gorillaz. It was her first time winning that award. A decade later, she became the first artist in history to win it twice.

The day that Harvey won that first Mercury Prize happened to be September 11, 2001. Harvey had been gone from New York for more than a year at that point, but New York was still inscribed onto the album. After that day, it became impossible to hear Stories From The City the same way. When "You Said Something" plays, I think about the rooftop in Brooklyn, the lights flashing in Manhattan. I think about how the view changed, how many of those lights no longer exist. I'm guessing Harvey does, too. In the fall of 2001, Harvey was touring North America. The day she won the award, she was in Washington, DC, and she saw the wreckage of the Pentagon from her hotel room window. Harvey phoned into the Mercury Prize ceremony and sounded utterly shellshocked.

Harvey never even flirted with mass appeal after Stories From The City. Instead, she moved in more harsh and extreme directions, often brilliantly. This wasn't a surprise. Harvey was always a restless artist. She always moved on. Stories From The City was a moment for her, and for me, and for everyone else who heard it. Shortly after the album's release, worlds changed, in ways both normal and not. In the past 20 years, I haven't returned to Stories From The City the way I have to Dry or Rid Of Me or To Bring You My Love. But that has less to do with the quality of the album itself, which rules, and more to do with the strange and uneasy and short-lived moment that it captured. When I think of it, I think of it fondly. I hope PJ Harvey does, too.