Robert Beatty didn't set out to make covers for albums, exactly. He'd always been an artist as a kid, and when he got older he played in the noise band Hair Police. His earliest forays into album artwork were really moments of DIY happenstance: Hair Police did everything themselves, and that meant he wound up creating all the visual art to accompany their music. Then a few friends asked for art too, and then as the years went on Beatty found himself slowly turning this into a full-time gig.

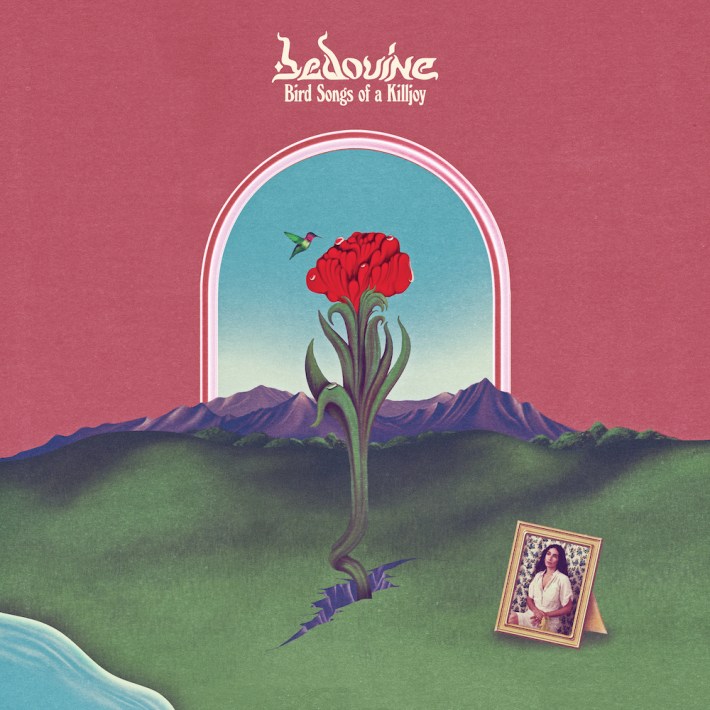

Since then, Beatty's become a prolific designer behind album covers, posters, and the occasional commercial campaign. You have seen his work: Most prominently, perhaps, on major-label albums like Tame Impala's Currents and Kesha's Rainbow, but also with recurring collaborators like Ohsees and Oneohtrix Point Never, and with everyone from the Flaming Lips to Bedouine to U.S. Girls to Ariel Pink to Ed Schrader's Music Beat.

Along the way, Beatty carved out a specific aesthetic. In his earliest days, he adopted a kind of crude psychedelia and garnered notice for the airbrushed quality to his work. Over time he has refined and expanded his palette, corralling detritus from across the decades to combine old-school elements with new techniques and winding up with surreal images all his own. Beatty might find inspiration from obscure movements and cult artists of the past, but he's also never looking to go fully retro. What you get, instead, is images filtered through an idiosyncratic eye, covers that feel classic but askew at the same time. Many of his best exist in a time and place all their own.

Beatty's been plenty busy over the years as is, but you've certainly seen a lot of his work in 2020. His art has provided covers for Tim Heidecker, Tobacco, and Ziemba in recent months, but perhaps most notably he's rejoined his old friend Dan Lopatin of Oneohtrix Point Never for next week's sorta self-titled Magic Oneohtrix Point Never. It became a bit more of an expansive project, extending beyond the cover art into Beatty and Lopatin collaborating on a whole mood and atmosphere for the album. Ahead of its release, we talked to Beatty about the business and art of album covers, and what it's like working with musicians on this facet of their releases.

STEREOGUM: I know you got started doing art for your band Hair Police, and you were an artist growing up. Was there a specific turning point along the way when you realized this was the thing you could pursue as your career?

ROBERT BEATTY: There’s not really any one moment where it just clicked. There was definitely a point around 2011, 2012, when Hair Police was slowing down with people in the band being in college or being in other bands. I was working, doing odd jobs here and there but mostly doing renovation on old houses. I had a little bit of time on the side and it was really just a few other people started asking me to do artwork for them, people I had met through touring. The way everything has developed has been very organic. I live off my art, and I can’t even really tell you when I started doing that, because it’s been such a slow, gradual process where I stopped doing other work.

STEREOGUM: There are some tropes within your work: this out-of-time aspect, the illustrative approach, pulling from psychedelia and sci-fi. How did you develop this style? How did you settle on this set of imagery?

BEATTY: I have a hard time pinpointing exactly where certain things come from. I’m really interested in stuff transforming or melting, I think that’s just something that worked its way in from my subconscious. It’s one thing that’s always there.

A lot of the stuff I draw from is old experimental film and experimental animation from the ‘60s to the '80s. That's definitely a lot of where the seeds for this stuff is coming from. Stuff like, Lillian Schwartz was an early computer filmmaker. Her stuff is a really important touchstone for some of the stuff that I’m doing that’s less in the airbrush style but more in that weird digital art realm, I guess you could say. There's a ton of Eastern European and Japanese animation -- that's not anime style, that's more out-there experimental stuff -- that has been a huge inspiration for me. There’s this Russian animator Vladimir Tarasov that made all these insane science fiction shorts in the '70s and '80s.

A big part of what I do is taking a lot of different influences and trying to synthesize something new out of them. I don’t necessarily think what I’m doing is something new. [Laughs] But I'm trying to do it in a way where it at least feels like it has a little bit of my personality and my touch in it and it kinda brings together a lot of different things. I’m not averse to wearing my influences on my sleeve but I’m not trying to make something that is retro, or whatever. I’m trying to take things that are obscure or slightly forgotten and turn it into something that feels new. It’s been cool the way this has developed because I think a lot of the bands I work with have a similar approach to things.

STEREOGUM: How did you find all this stuff? Like, was this just weird internet corners you stumbled down? Like you said, a lot of it is pretty obscure.

BEATTY: A big part of how I got into what I'm interested in was when I was younger. I grew up before the internet was really accessible. It was a lot of magazines and books -- I didn’t go to school at the University Of Kentucky but I spent a lot of time at the art library there. I discovered old design manuals that would have the best animated shorts or commercials made in like, 1972. I would just look up that stuff. I’ll follow every thread that I can until there’s a dead end, when it’s something I’m interested in.

STEREOGUM: When I look at all the covers on your site, there's connective tissue even if there was a different kind of aesthetic earlier on than there is now. I was looking at the last year or two, and there’s stuff like, for example, the Dream Syndicate, Bedouine, and Mdou Moctar albums that feel like there’s a shared visual language.

BEATTY: There’s definitely a common thread through a lot of my work. I know people see it and think, "Oh, that's Robert." But to me, all of this stuff feels like it’s part of something outside of me. All of these things relate to each other in a certain way. All those [covers], it’s a similar psychedelic desert kind of thing. The William Tyler cover that I did, as well. That one and the Bedouine cover, I think I was working on them at the same time -- they were different views of the same world.

It’s weird, I've kinda gotten to the point where I'm maybe trying to escape myself a bit, trying to get away from what people know me for or want the most. It kind of goes back to, you know, starting out, figuring all this stuff out, I didn't know what I was doing. I'll look back on some of the covers I did 10 years ago or something and I don't remember how I did it. I wish I could get back to making something that looks a little more crude and simple than what I'm doing now. I kinda wish I could revert a little bit. I almost feel like it’s too easy now or something. [Laughs] I want to do something different and challenge myself a bit.

STEREOGUM: How does the process usually work? Like if someone comes to you because they like your work, would they also already have a treatment for the design in mind?

BEATTY: It’s pretty wide open. Sometimes people will be very specific and even go as far as to give me sketches of a specific composition they have in mind. Then other times people have a vague idea of the themes of the record and want to see what I come up with. It runs the gamut. Sometimes, somebody will want one thing and I'll do it and we end up taking everything away and there’s one tiny element of that left. It’s a completely different process for every record.

STEREOGUM: Are there times where you don’t get to hear the album?

BEATTY: There’s definitely a few occasions where that’s happened. With, you know, bigger artists.

STEREOGUM: Right, like Tame Impala and Kesha.

BEATTY: Both of those, I think I'd only heard a couple songs while I was working on the cover. The lead singles or whatever. That’s kind of more dependent on my relationship with the artists themselves, if it’s someone I know or have mutual friends with. That’s been an interesting thing, navigating those relationships. I came from a total DIY background, being in a band where we did everything ourselves -- that's how I ended up doing artwork. It's interesting doing an album cover for an artist and never communicating with the artist directly. Usually there’s some, but a lot of times these days I'm dealing with managers or record labels as much as I'm dealing with the artists themselves.

STEREOGUM: If you can only hear one or two songs, it seems like it’d then be pretty hard to create a visual companion for that album.

BEATTY: It varies from project to project. Usually bands will have some sort of frame of reference for the artwork, whether that’s outside references or work I've done in the past. Like, "We like this thing, combine it with this other thing." There’s certain bands I can make a cover for without hearing the music just because I know their previous albums or I know the world they exist in.

STEREOGUM: Would Osees be an example of that? You’ve done several for them.

BEATTY: [Laughs] A little bit. But pretty much all of those covers, John Dwyer sent me a shitty collage and was like, "Can you make this?" He’s very dialed-in and specific about what he wants and it’s great because it’s almost like a weird paint-by-numbers kinda thing. An Odd Entrances, the one with the centipede coming out of the ear -- he literally texted me a photo that was a collage he’d made from Google image search that was a centipede coming out of an ear. He’s definitely an outlier in that regard. Most people just don’t know what they want that clearly.

STEREOGUM: The Kesha cover also had a photographer and an art director involved. Have there been a lot of instances where you've found yourself a part of a bigger operation where it turned into more of a collaborative or team-based effort?

BEATTY: For sure. I feel like a lot of other people who do album artwork do that a lot more than I do. Typically, most of the time, when I'm working on something I'll do everything, down to the layout, the print production. I'm kinda very hands-on in that way. That one was a pretty unique situation in that Olivia Bee was taking the photographs and Brian Roettinger was art-directing the whole thing. He's the one that reached out to me about working on that.

STEREOGUM: So he had a concept and thought you were the guy to help make it happen?

BEATTY: Basically he was assembling the team to work on the album artwork. But Kesha had specifically requested me for that. She knew my work through the Tame Impala and Flaming Lips covers and some other things. She mentioned my name to Brian, who’s somebody where we have lots of mutual friends but we hadn't worked together before. He’s definitely playing a different role than I’m interested in. He’s art directing massive campaigns for like, Jay-Z and Florence + The Machine. He does tons of huge bands. I’ve realized that’s not for me. You’re doing ads and videos and stage setup. You’re art directing all of that. Maybe if I lived in New York or LA and could be more hands on with it, but I’m just not of the mindset to work that way. I’m much more interested in doing my one small part.

STEREOGUM: I know you might not want to give everything away, but I’m curious about your artistic process as well. I know there’s some blend of digital and organic, like using a computer but trying to make it look a little handmade.

BEATTY: It’s really just trying to emulate older techniques, whether that's airbrush stuff or early computer art. I feel like what I’m doing isn’t technically that complicated. It’s all pretty simple. I’m just using Photoshop straight out of the box, I’m not using any plug-ins or anything fancy. It's the same program everyone else has. I like that, in that regard, like it’s this even playing field. Everybody that has access to Photoshop has access to the same tools, basically. I think more than the way I do things it’s how I’ve ended up where I am, by just constantly trying to learn new stuff. Going back to what I was saying before, being inquisitive. If I see something in a movie or something, I’ll want to know how they made that. Obviously if it’s from the '70s, they’re making it on film. It's trying to wrap my head around that process and whether I can recreate something similar in a computer, using modern software, and get something that feels the same. It's a lot of breaking processes down and looking at the tools you have available.

STEREOGUM: What's the general timeline for these projects? Like how long might an album cover take vs. knocking out a poster?

BEATTY: It varies, it depends on the lifeline of the project and how in-depth it is. Like the Tim Heidecker cover, I think they contacted me late last year about that. The record was almost done and they were doing some overdubs and stuff. I don’t even know if they knew what label was going to put it out, it was just, "Are you interested?" My friend Drew Erickson produced that record, he plays keys in the touring version of Neon Indian -- he contacted me. That was probably in December, and I probably started working on it in April and finished it that month. Something like the Oneohtrix Point Never cover, I think Dan contacted me about that late last year, maybe around this time, so that's maybe a yearlong process.

STEREOGUM: Yeah, I wanted to dig into your work with him more. I know you’ve been collaborators for a long time after you met on tour when you were younger, and I know you’ve said doing the cover for R Plus 7 was a big deal for you since it was your first cover for Warp.

BEATTY: Oh, yeah, I listened to Squarepusher and Aphex Twin and all that stuff from a young age. It’s cool that it happened, and it’s cool that it happened in a pretty organic way. Like, just because I met Dan before he had even started Oneohtrix Point Never. I played a show with him in Boston, he had a synthesizer trio called Astronaut. It was just straight-up Tangerine Dream-style cosmic synth music. It was cool that it was actually somebody I know getting signed to Warp that made it possible for me to do something with them.

STEREOGUM: It's interesting you have this ongoing thing with him, back then and now teaming up again for Magic Oneohtrix Point Never. To me there's something similar to your artistic approach and his musical approach, these kind of weird obscurities and digital haze of far-flung touchstones. Especially how your aesthetics are meeting for this new project, it’s like this corroded VHS vibe.

BEATTY: Yeah, a little bit. I think it will be more clear, once all the album artwork is out, what we were going for. Obviously Dan has had that for a while; a lot of his music videos have this weird "found YouTube" kind of vibe. With this new album, we spent as much time talking about what we were going to do as we did actually doing anything. Dan had the concept when he first got in touch, and we both just talked about what we'd been into, and there was a lot of overlap between the things we were interested in at the time. It was nice weird serendipity.

Honestly, Dan’s last couple records haven’t really been my thing, and he knows me, so I think he knows that. [Laughs] I think he was like, "I think I’m going to make a record you could do artwork for." This record is definitely a return to form a little bit, but it's also breaking new ground, and we tried to highlight that a bit with the artwork. There’s a lot of references to stuff we've done in the past. There's a lot of references to things he’s hinted at. The whole album is kind of based around this idea of it being a radio station. Like, the name Magic Oneohtrix Point Never comes from the radio station Dan named the project after. So [the album] is this kind of morning to evening radio listening session. A lot of the artwork is trying to push the narrative that’s in the album. There’s a lot of stuff that’s referencing old radio station and muzak ads.

The way that I'm doing this stuff is different than the way Dan is doing it. He samples a lot of stuff. Everything that's in this album, I made entirely from scratch, even if it looks like something that’s found materials. It was basically me recreating ads from old magazines or weird New Age catalogs. It was trying to take all of this stuff and mulch it together and make something totally new out of it. It's a slightly different approach but I feel like it gets across a similar idea to what Dan’s doing with his music.

STEREOGUM: This sounds like a unique project in terms of the expansiveness of it, the idea you two were creating this whole world together. On a certain level, it's almost like that art direction you said wouldn’t be for you with some bigger artists.

BEATTY: For sure, I'm definitely doing the thing I don't want to be doing. [Laughs]

STEREOGUM: But it's different with him right? Like, is he an artist you relate to enough that you'd make that exception or are there other artists where you could see yourself getting into their headspace like that?

BEATTY: Dan is somebody I've known a long time, but I think the big thing here is Dan knows me. He doesn't just know my work, he knows what I'm interested in, what I'm interested in doing, and what I'm capable of doing that are things people maybe aren't always coming to me for. It's been refreshing. I love being able to do what I do, but I get stuck in a rut, repeating myself a bit. The work I did with Dan for this album, it feels like new territory and kind of a different thing that I've not ever really done before.

It's funny, the last couple albums he's done have been massive. Obviously with the MYRIAD shows for Age Of. He turned this whole thing into this massive production. When he first contacted me about this one he was like, "I think... this one's just going to be an album, I’m not going to do all this extra stuff." Because of coronavirus, it’s kind of turned out that way. But also, it's gone -- there’s already stuff where I'm like, "This is kind of turning into a production, Dan." [Laughs] I'm happy to work on it. Everything's been really fun to do. The album artwork's been done for months now, but I’m still doing stuff. The way we're presenting this stuff… it's not even a ghost of the past, it's somebody trying to make what they think a ghost of the past would be. Just really starting from scratch and trying to create a world that could be a world that once existed.

Me and @0PN scoured CB/Ham radio magazines, new age/self help books and cassettes, radio station ads, Muzak brochures, QSL cards, early computer gaming magazines, and so much more as inspiration. Had a lot of fun making all this up from scratch, hopefully it shows.

— Robert Beatty (@EdSunspot) October 30, 2020

Some of this stuff came together in a few minutes in an almost automatic way, some of it took a long time to get right. Definitely felt like I was in an ephemera-induced trance a few times while working on this.

— Robert Beatty (@EdSunspot) October 30, 2020