"They had a plan." That was the late Chester Bennington, just before his 2017 death, reflecting on the first time he met his Linkin Park bandmates. That plan is what attracted Bennington to the band. At the time, Bennington was just past 20, but he was already done with the music business. Bennington had spent five years in Grey Daze, an Arizona grunge band. Grey Daze had self-released two albums, and they had a local following, but they never went anywhere outside the Phoenix area. Bennington was looking for stability. He married young, and he got a job at a digital services firm. He wasn't going to be a rock star. But then Jeff Blue, a music exec who knew Bennington a little bit, told him about a Los Angeles rap-rock band who needed a singer. If you were a young man looking for stability, then you could see why joining Linkin Park was a pretty good bet.

Linkin Park were, and are, professionals. They were always businessmen, never hedonists. In a nu-metal world full of party-hard jokers and outsized personalities, Linkin Park were practically monks. They didn't engage in rock-star hijinks. They wrote lyrics so broad and relatable that they could fit just about any dark-night-of-the-soul context. Their music only barely scanned as metal, and they took more, both lyrically and aesthetically, from Depeche Mode and Echo And The Bunnymen than from Helmet or Pantera. They attacked their soul-wracking self-exorcisms with a businesslike precision. They didn't even cuss on records. And they eclipsed all of their peers.

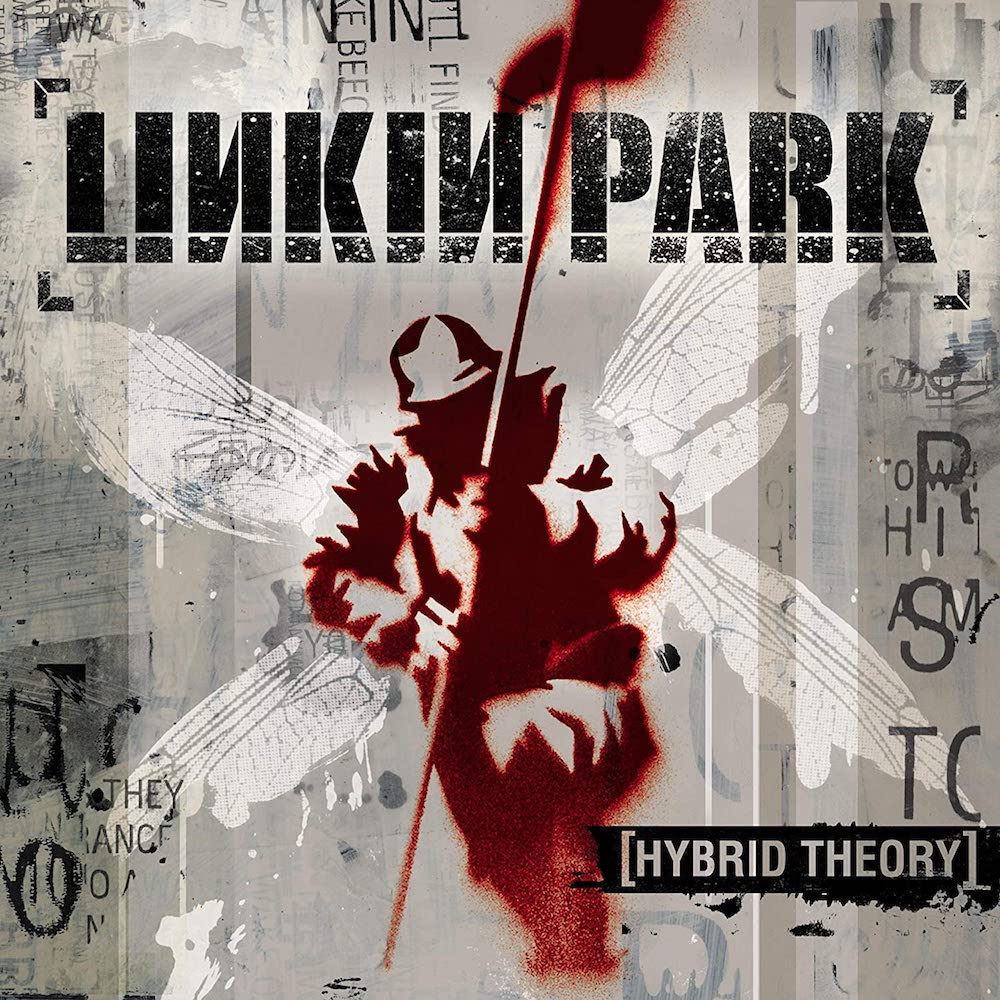

Linkin Park's debut album Hybrid Theory, which turns 20 tomorrow, has sold 12 million copies in the US alone -- more than any debut album from any rock band not named Guns N' Roses. It's America's best-selling rock album of this century, and it probably still will be when the century ends. The plan paid off.

[videoembed size="full_width" alignment="center"]https://youtube.com/watch?v=4qlCC1GOwFw[/videoembed]

If you first encountered Linkin Park in the early days of the Hybrid Theory album cycle, then you might not have seen the plan at work. You might have thought the whole thing was a joke. I did. "One Step Closer," the band's first single, was, on first glimpse, pure goofiness. Two singers -- one howling about how mad he was, one adding choppy almost-rap hypeman interjections. A guitarist who wore headphones. A DJ who did not wear headphones and who did a scratch solo on the breakdown. At the time, there were hordes of bands like this -- offering similar tantrums, with similar aesthetics -- invading the rosters of the various major labels. Most of them were too late. Linkin Park were right on time.

Linkin Park showed up in the waning days of the nu-metal boom. Korn and Limp Bizkit were still huge, but they'd already peaked. Kid Rock was already in the early stages of his Southern-rock transition. Slipknot and Static-X and Coal Chamber and most of the other big rap-metal bands had already released their biggest albums. (P.O.D. were still ascendant, but they had the Christian thing going for them, so they could afford to be late.) A week before the release of Hybrid Theory, Limp Bizkit had dropped their third album Chocolate Starfish And The Hot Dog Flavored Water -- a huge hit, but one that couldn't match the sales of 1999's Significant Other. If you were a smartass college student, as I was, then Fred Durst had already entered his punchline stage. Nu-metal was on the way out. Did anyone need another band like this?

For weeks, maybe months, my friends and I clowned "One Step Closer." If we were sitting around drunk, as we usually were, then someone would yell, "Shut up when I'm talking to yoooouuuuu!" and everyone else would laugh. When "One Step Closer" showed up on the soundtrack of Dracula 2000, a movie that we paid money to see for some reason, we all cracked up.

But I couldn't shake "One Step Closer." Something kept pulling me back to it. There was the gleam on that opening guitar riff, the weirdly satisfying use of the old quiet-to-loud dynamic, the sense of space in the beats, the lead singer's pained and nasal yowl. The song moved. It had some weird gravity working for it. It was the same sort of impotent-rage teen-angst anthem that every other nu-metal band was offering, but it was somehow sleeker, smarter, more. Eventually, I found myself being the one asshole in the car who was trying to say that "One Step Closer" was really pretty good if you thought about it, while everyone else clowned me for it.

Maybe I was responding to the professionalism. That, more than anything else, is what set Linkin Park apart. The band came out of four-track experiments that Mike Shinoda put together in his suburban-LA garage in the mid-'90s. Shinoda loved rap music, and he also loved Rage Against The Machine and the Red Hot Chili Peppers. Shinoda and some high-school friends put together a rap-rock band called Xero. People who heard Shinoda's demos commented on how clean they sounded -- how they didn't sound like the work of a teenager with a four-track.

At the time, Xero guitarist Brad Delson was interning at the music publisher Zomba. Zomba vice president Jeff Blue, the guy who'd signed Korn and Limp Bizkit to songwriting deals, took a liking to Delson and his band. When Xero's singer went off to join a Christian ska-punk band -- this was, after all, the late '90s -- Delson helped them find a new singer. He introduced them to Chester Bennington.

Linkin Park never spent any time in any sort of underground. Instead, they set sights on mass acceptance straight away. Blue had them playing showcases around LA for different labels, most of which passed on the band. Finally, Blue got a job at Warner Bros., and he made signing Linkin Park a condition of his employment. The members of the band have talked about how label A&R guys got nervous about the rapping and tried to break the band apart and remake it. The execs knew Bennington was a star, but even at the height of the rap-metal boom, they weren't sure about Shinoda's rapping or Joe Hahn's DJ'ing. Linkin Park only remained intact because Bennington stood by his new bandmates. The "shut up when I'm talking to you" bit that my friends and I enjoyed so much was Bennington yelling at Hybrid Theory producer Don Gilmore, a guy who'd worked with poppy alt-rock bands like Lit and Eve 6 and who, in the band's view, was a little too quick to defer to those nervous A&R guys.

Shinoda, the mastermind behind Linkin Park, wasn't really a metal guy. When he talks about Linkin Park's influences in interviews, he talks about relatively esoteric stuff -- Aphex Twin, DJ Shadow, the Roots, Timbaland. But the rap-metal boom was obviously an opportunity, and Linkin Park made the most of it. Shinoda rocked the spiky Kool-Aid-red hair in the "One Step Closer" video. Linkin Park played OzzFest and the Family Values Tour. The band even did the creative-misspelling thing.

Originally, Linkin Park had planned to call themselves Hybrid Theory, but the existence of the British dance group Hybrid made that a no-go. So they kept Hybrid Theory for the album title and picked a new band name. They'd considered calling themselves Lincoln Park, after the Santa Monica enclave, but they changed the spelling because the LinkinPark.com domain name was still available. As far back as 1999, Mike Shinoda was thinking about search-engine optimization -- the mark of a true professional.

Listening to Hybrid Theory now, a few things are striking. There's the clear debt that Linkin Park owe to Nine Inch Nails, whose big programmed beats and ultra-processed guitars were the clearest possible antecedent. There's the lack of specificity in the lyrics -- the way "I" and "you" and maybe "time" are the only characters on the LP. There's the force of personality that Bennington brings -- the guy clearly knew his way around a big hook and understood how to invest his screams with stadium-sized catharsis. And there's how sad the whole fucking thing is.

"In The End" is Linkin Park's biggest hit, and it's also the moment that people mostly stopped making fun of Linkin Park. (The single peaked at #2 on the Hot 100, stalling out just behind Jennifer Lopez and Ja Rule's "Ain't It Funny." Maybe Linkin Park would have a #1 hit if Bennington had opened "In The End" by yelling that it must be the aaaaass that got him like that.) "In The End" has a miserable grandeur that's hard to overstate -- a colossal, crashing sense of operatic futility. Bennington's suicide obviously puts a song like that in stark relief, but the hook on that one -- "I tried so hard and got so far, but in the end it doesn't even matter" -- is just a gut-wrench, the type of thing that some of us only feel in our darkest moments.

There's a whole lot more of that on Hybrid Theory. "One Step Closer" aside, Hybrid Theory isn't really an aggressive record. There's no tough-guy posturing, even on something like the straight-up arena-hardcore breakdown at the end of "A Place For My Head." Instead, there's longing and depression. Shinoda raps about wanting to get away from everyone, to disappear. Bennington screams that he's crawling in his own skin. As a frontman, Bennington put his vulnerability front-and-center, bringing stadium-singalong reach to a phrase like "so insecure."

Hybrid Theory is, on some level, a fundamentally teenage album, an album about feeling like the world doesn't understand you and like you just want everyone to get out of your room right now. That teenage quality is the greatest strength and the greatest weakness of Hybrid Theory. The album is repetitive and one-note. The singles often sound huge and overwhelming, but the album tracks usually just wear me out. I don't think it's a great record, but then, I'd just gotten done with being a teenager when it came out. If I'd been maybe four years younger, that shit could've just kicked me right in the soul.

But Linkin Park didn't ultimately need my approval -- or, for that matter, the approval of any critics. (I wasn't a critic yet, but I was already thinking like one.) The band did just fine on their own. They moved beyond nu-metal, honing their style into a shiny, streamlined catharsis-machine that proved a whole lot more culturally durable than what any of their peers were doing. Their sound -- compressed to death, ultra-processed, painstakingly studio-assembled, lab-perfected -- had legs.

Hybrid Theory became the biggest-selling album of 2001 despite never once hitting #1 on the Billboard album chart. The sophomore LP Meteora came out in 2003, when garage rock and Brooklyn dance-punk were supposedly all the rage, and it sold seven million copies in the US -- or, to illustrate the state of things more clearly, Is This It times seven or Room On Fire times 14. Linkin Park made seven studio albums, and only their final one, 2017's One More Light, went anything less than platinum. Their damn remix album went platinum. Their goofy Jay-Z mash-up experiment went double platinum.

In the early days of Linkin Park's dominance, a lot of us made fun of the band for being whiny suburban kids in love with their own anguish. Today, it's tragically clear that Chester Bennington had always had real demons -- a history of sexual abuse and substance dependency that he'd discuss at length whenever anyone asked. Hybrid Theory was a product, a laser-calibrated angst-engine sold to America's teenagers in the closing days of the CD era. But every album is a product. Listening to Hybrid Theory today, I'm struck by the thought of how many kids found real solace and relief in an album like that, and how Linkin Park had a plan to get it to them.