I remember exactly where I was the first time "B.O.B." hit. It's not the kind of thing you forget. I remember everything about it -- the tingly music-box intro, the whispered count-off, the sudden adrenaline-jamming surge of booming bass and rampaging drums and needling dubbed-out electric guitars, the way that adrenaline surge didn't let up over the next five minutes. I remember all those sounds and ideas pinging around in my head as I walked across that parking lot. I remember the sunlight reflecting off of the windshields of the cars around me, the faces of the people walking past, the air suddenly tasting a whole lot more vivid in my lungs. It's all tattooed in there. It's never leaving. I won't let it leave.

This would've been September of 2000, a month and a half before Stankonia landed. A couple of CD singles had shown up at the college radio station where I was volunteering, and I immediately stole one. Didn't even think about it. Grabbed one, shoved it in my pocket, walked out of the student center all paranoid, like I had purloined diamonds jammed in my boxers. Threw it in the Discman as soon as I was sure nobody else from the station was watching me. Felt my brain shatter right away.

I would like to tell you that the arrival of "B.O.B." felt like some kind of big-bang moment -- that I knew the rules had been shattered and nothing would be the same again. That would be a lie. I didn't have the mental bandwidth for anything like that in the moment. My reaction was something more like: "What fuck whoa holy shit fuck whoa what." I kept hitting repeat, trying to make some kind of sense of everything I could hear. It wasn't working. I couldn't do it.

"B.O.B." felt like everything happening at once. It sounded like a futuristic rave divebomb attack, and it also sounded like a widescreen take on circa-1990 Miami bass, an entire genre that I'd been conditioned to think was stupid. Andre 3000 and Big Boi's verses zoomed all over the track like runaway remote-control cars, moving too quickly to let me process anything they were saying. Other sounds kept showing up and disappearing -- jittery 808 breakdowns, gospel-whoop massed-choir shout-alongs, pinging electro-bleeps, swampy guitar chicken-scratches, nattering DJ scratches, a climactic Hendrixian solo. It was overwhelming, and it made everything else suddenly sound small and timid. I couldn't believe that a song like this existed. It didn't seem real. It seemed like a dream.

When the music video arrived shortly thereafter, it made the whole thing seem even more like a dream. Andre 3000, shirtless in leather gauntlets and banana-yellow pants, sprints across purple grass under impossibly blue skies, as a whole housing project full of kids chases him in some new-millennium Beatlemania freakout. Big Boi jumps between highway-speeding big-body slabs like he's the Road Warrior. They arrive together at a utopian throwdown in some kind of church/club hybrid, where they're surrounded by choirs and dancers and at least one baboon. Then they embark on a seven-light-year journey to some place called Stankonia, their cars turning into astral blurs. This was not the kind of thing I was accustomed to seeing on my dorm's common-room TV on a mid-afternoon Rap City episode.

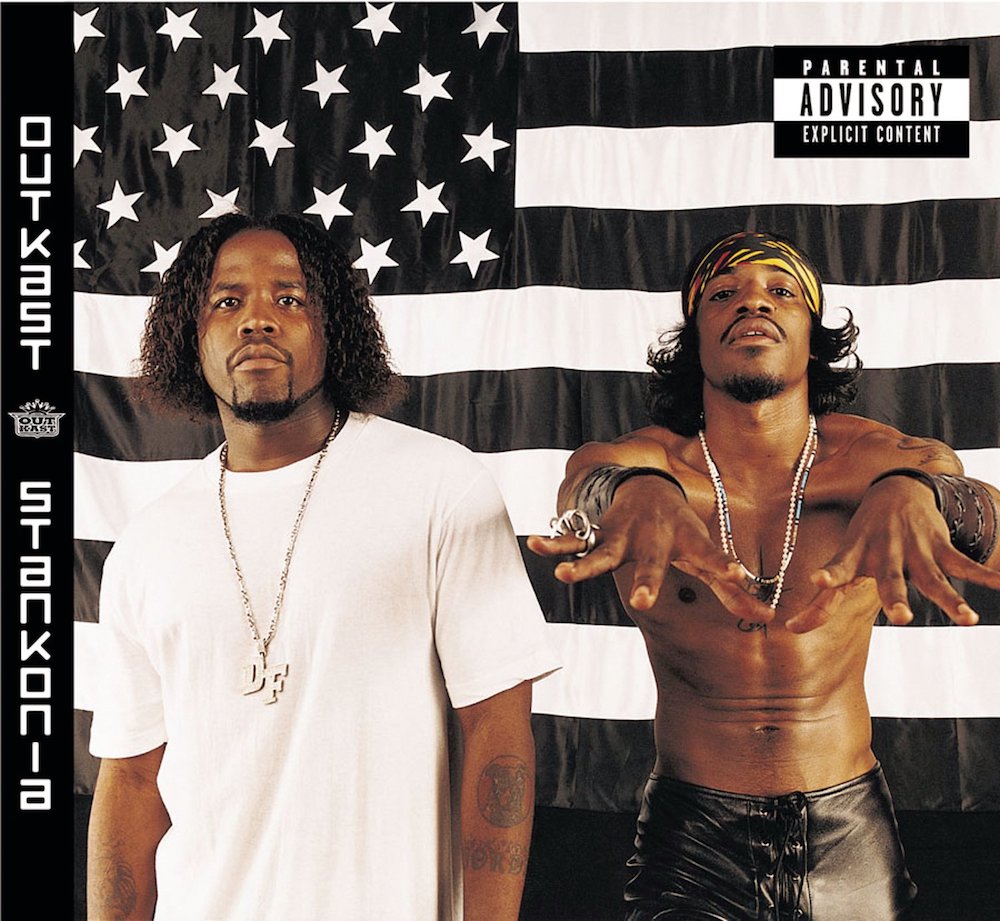

Stankonia was an actual place, though it wasn't seven light years away from the "B.O.B." video shoot. After the success of their third album Aquemini, OutKast moved out of the Dungeon. They bought their own studio, the place that had formerly been known as Bobby Brown's Bosstown, and they spent a year experimenting and tinkering and honing and perfecting, coming up with a sound that was at least a couple light years removed from what everyone else in rap was doing. Rap music had effectively colonized the pop mainstream years before Stankonia arrived, but OutKast saw something else happening -- the pop mainstream colonizing rap music. "They’re real comfortable out there right now," Big Boi told SPIN. "Nobody’s hungry anymore." OutKast were still hungry.

They didn't have to be hungry. Aquemini, like 1996's ATLiens before it, had gone double platinum. Rock critics had figured out something that even casual rap listeners had figured out years earlier -- that OutKast were boundary-shattering funkateer geniuses in the midst of an all-time run. After the release of Aquemini, OutKast spent the fall of 1998 opening for newly crowned crossover superstar Lauryn Hill on tour. Their legacy and their star status were both secure. They could've chilled. They could've got real comfortable. But that's not how they were wired.

Instead, OutKast spent months jamming with local musicians recruited from Atlanta's club scene. André 3000 spent long days at home, playing around with a guitar and sketching out new song ideas. He got less into rapping, more into singing -- and when he was rapping, his rapping took on more of a spoken-word spaciness. André and Big Boi remained tight with their Dungeon Family crew, but they moved further away from Organized Noize, the groundbreaking production collective who'd first discovered them. Instead, they figured out how to handle their own production.

OutKast and Big Boi formed a new production collective called Earthtone III with Mr. DJ, their touring DJ. The new collective made its debut in 1999 with "Neck Uv Da Woods," OutKast and Mystikal's sputtering and rumbling contribution to the soundtrack of The Wood. From there, they went straight into doing the vast majority of the production on the next OutKast album. That's a big leap.

In interviews at the time, OutKast made sure to mention that they weren't really listening to rap music -- that rap music wasn't inspiring them. Instead, they were off on their own separate musical visual quests. Big Boi talked about Kate Bush. André talked about Photek. There was certainly a sense of competition with the rest of the rap landscape -- Stankonia, after all, was not the duo's first time sharing a release date with Jay-Z -- but there was a remove, a sense of separation, both from the rest of rap music and even from each other. The duality at the heart of OutKast, the yin-and-yang combination of Big Boi and André's respective styles and outlooks, was always one of the duo's most powerful advantages. But making Stankonia, Big Boi and André were further-removed from one another than they'd ever been.

André reportedly came up with many of his parts at home, while Big Boi spent most of his time in the studio that the two halves of the group had bought together. When they toured behind the album, Big Boi and André took separate buses. (André had quit smoking weed. Big Boi had not.) There are plenty of tracks on Stankonia that just feature one member of OutKast, not both. Even when both members of the group are united, you can usually imagine which half of the group was the animating force behind each song. The two clashed in the studio, with Big Boi reportedly taking exception to all the singing that André was doing. Shortly after the album's release, Big Boi and André were already talking about the idea of making their next album a double LP, with both members working on their own solo music.

That tension is woven into Stankonia. Stankonia will never be my favorite OutKast album, mostly because of its frantic idea-hopping can be so overwhelming. OutKast had made miracles by figuring out how to balance their competing impulses, to channel their tributaries into the same river. On Stankonia, the sound frayed and fried, pulling each other and themselves in different directions. The tracks can be almost jarringly overstuffed, with ideas flying furiously. But OutKast made that tension work for them. That tension pushed them to different levels, and it's key to the power of Stankonia.

A song like "B.O.B." shows just how productive that tension could be, but that's only the start of it. You can hear it in the intensity fuck-shit-up theatrics of "Gasoline Dreams," the whispering sidelong funk of "Spaghetti Junction," the nervous pitter-patter of "Humble Mumble," the scattered and discordant push-pull of "?," the psychedelic robo-soul meditations of "Stankonia (Stanklove)." These are dizzying, ripped-apart tracks, and they find their own internal logic.

For me, the best moments of Stankonia are the ones where one half of OutKast bends to meet the other but ends up twisting the track into some unpredictable new shape. Consider "Gangsta Shit," which sounds like a straight-up old-school Dungeon Family throwdown -- a total Big Boi track -- before André jumps onto the end of the track and sends everything spinning. André is just as hard and snarly and on-beat as his comrades, but his definition of gangsta shit is very much his own: "OutKast with a K, yeah, them n***as are hard/ Harder than a n***a tryna impress God/ We'll pull your whole deck, fuck pulling your card/ And still take my guitar and take a walk in the park."

In one of the album's most memorable moments, André defends the straight-up rap culture that Big Boi tends to embody: "I met a critic, I made her shit her draws/ She said she thought hip-hop was only guns and alcohol/ I said/ Oh hell naw!,' but yet it's that, too/ You can't discrimi-hate cause you done read a book or two." "It's that, too" is the crucial part there. A more reductive rapper would've disavowed the guns and alcohol. André remembers that they're crucial parts of a whole, even if they're no longer the parts that speak to him.

Big Boi, meanwhile, dominates the album's most abrasive track, and maybe its most experimental. "Snappin' & Trappin'" introduces the commandingly hungry Killer Mike to the world, and it's the sort of brain-rattling sonic attack that, at the time, I generally associated with underground boundary-pushers like Company Flow. Maybe I shouldn't have been surprised when Killer Mike and El-P made such a potent combination more than a decade later.

Stankonia went gold in a week and quickly became OutKast's biggest album, and I think its reputation has gotten a little inflated in the process. The LP is crucial to the cult of André 3000. All the recent sightings of André playing flute in city parks are signs that he's inching toward Billy Murray-style internet folk-hero status, and so you can look at Stankonia as the moment that André truly broke free of gravity and went into orbit. But not all of André's lines have aged well. "You're so Anne Frank" remains an extremely weird thing to say to a woman you're wooing. Or think about this: "Bill Gates don't dangle diamonds in the face of peasants when he Microsoftening the place." This was a standard crunchy-rapper move at the time, an anti-materialism that spoke to a certain wisdom. But from a distance of a couple of decades, Master P looks like a figure much more worthy of emulation than, say, Bill Gates.

Big Boi has his own bits that he might take back if he could: "She tried to pull my rubber off with her pussy muscles, that was wrong/ The bitch is no good like lesbians with no tongues." But Big Boi also gets many of the most verbally vivid moments, the pure-rap blackout-zone bits that now seem almost impossibly creative: "Loving, lavish, ladies, leaving landmarks of lemon-lime lip gloss on your lavender lapels, leaping lizards!" André has plenty of dazzling moments on Stankonia, but I'm not sure I love any of them as much as I love Big Boi claiming to be cooler than Freddie Jackson sipping a milkshake in a snowstorm.

The magic of the Big Boi/André push-pull is still fully evident in the song that took OutKast into the stratosphere. When I first heard it, I was convinced that "B.O.B." was about to become the biggest song in the world. I was wrong; it missed the Hot 100 entirely. But OutKast's very next single, a relatively low-key meditation on familial resentments and parental complications, did become the biggest song in the world. On "Ms. Jackson," André chooses a generic name to address his child's grandmother. Three years earlier, André and Erykah Badu had become parents, and André warmly and fondly promises to be responsible through the chaos: "Forever never seems that long until you're grown/ And notice that the day-by-day ruler can't be too wrong." But on the same track, Big Boi represents the flipside of that dynamic, venting rancor and hurt: "She never got a chance to hear my side of the story, we was divided/ She had fish fries, cookouts for my child's birthday, I ain't invited."

"Ms. Jackson" was an unlikely smash, but it was a smash nonetheless -- a tender and thoughtful and conflicted summer jam that arrived dead in the winter. In February of 2001, "Ms. Jackson" knocked Shaggy's "It Wasn't Me" out of the #1 spot on the Billboard Hot 100. OutKast had never even been in the top 10 before then. Suddenly, they were in top-40 rotation alongside Creed and Christina Aguilera and Crazy Town. Their next single was "So Fresh, So Clean," and it was both a victory lap and a throwback to their early Dungeon Family days. In the video, André and Big Boi hit synchronized dance moves and sat front-row in a church packed with famous friends and admirers.

[videoembed size="full_width" alignment="center"]https://youtube.com/watch?v=-JfEJq56IwI[/videoembed]

This was an affirmation. OutKast had already done everything you could do. They'd earned a five-mic review in The Source, something no Southern group had ever done. They'd landed a #1 single, something that no Atlanta rappers had managed since Kris Kross. (You could argue that Left Eye was an Atlanta rapper, but I'm talking about narratives here; bear with me.) OutKast had knocked out four masterpieces in a row, and they'd ascended to artistic and commercial peaks that nobody could've foreseen. It couldn't last forever-ever.

In retrospect, Stankonia is a frayed, fraying album. It's the sound of two lifelong friends running headlong in different directions toward an uncertain future. It's astonishing that they were able to make it work as well as it did. Stankonia is a work of stress and conflict and tension and chaos, and it splatters and shatters from moment to moment. But it's still the greatest rap group of all time operating at peak capacity, and it still holds together even as it breaks apart. Against all odds, OutKast would ascent to even higher mass-appeal levels in the years ahead. But they'd do it apart, not together.