Covers by Bad Wolves, Eminem, and Miley Cyrus lose sight of the song's initial spirit.

A few weeks ago, as part of the virtual Save Our Stages festival, Miley Cyrus covered the iconic “Zombie” by the Cranberries. “Zombie” is a notoriously difficult song to cover, but Miley managed it, the stratospheric chorus -- “In your he-ead, in your he-ead! Zombie, zombie, zombie-ie-ie!” -- proving a fitting vehicle for her raspy, full-throttle vocals. Praise flooded in from all quarters, with even the Cranberries themselves remarking that the late Dolores O’Riordan “would have been proud."

Beyond (deserved!) awe at Miley’s vocals, it struck me as odd that the meaning behind the words Cyrus was singing were so conspicuously absent from the conversation. I’m from County Antrim, Northern Ireland, and grew up during the tail-end of the Troubles -- a decades-long conflict in Northern Ireland in which thousands of people died over more than 30 years of routine violence, political complexity, and paranoia.

For those who aren’t familiar with the Troubles, presenting a potted history is tricky. Like many political conflicts, incredibly painful questions of identity lie at its core. The Troubles usually refers to the decades between the 1960s and the 1990s, when violence broke out between Northern Ireland’s unionist/Protestant majority, who believed that Northern Ireland should remain part of the United Kingdom, and a growing nationalist/Catholic minority, who wanted to see Northern Ireland reunited with the Republic of Ireland. With the nationalist minority in Northern Ireland increasingly becoming victims of social and economic discrimination, tensions exploded between the two communities, resulting in decades of bloodshed, a violent army occupation, and complete political dysfunction. If you’re interested, there are several guides that will explain this much more effectively than I ever could.

The aftermath of the Troubles still weighs heavily on Northern Ireland today. Growing up in the early 2000s, cultural segregation, political instability, and occasional violence were routine parts of my existence. It only struck me, when I moved to England for university, that most people don’t live in communities and attend schools segregated entirely by religion. Most people don’t have their city’s bus schedules regularly disrupted because of bombs. And most people certainly don’t spend Sunday dinner listening to tales of their parents spending their twenties queuing at army checkpoints and dodging British soldiers. Really, there are very few facets of Northern Irish life that the Troubles haven’t touched.

“Zombie” is not a neutral song; it is undoubtedly one of the Troubles’ most enduring and meaningful cultural artifacts. The song was written in response to a tragic 1994 attack in Warrington, England, in which two young boys were killed in an IRA bombing. O’Riordan had seen the bombing reported on the news and was upset by it, Cranberries guitarist Noel Hogan tells me over Zoom. “She said that she was really pissed off about this, and that this needs to be an angry song, that anger needed to be reflected in the music. We had the tendency to drown her out, but with ‘Zombie,’ we pulled that in a bit and had her vocals and the emotion at the front.”

And so “Zombie” was born: a raw howl of protest at the decades of senseless violence Ireland had experienced, with all the country’s rage, fear and frustration distilled into O’Riordan’s huge, anguished voice: “It’s been that same old theme since 1916,” O’Riordan cries in her thick Limerick accent, her vocals fluttering theatrically, her voice reminiscent of sean-nós, an ancient, theatrical style of Irish singing.

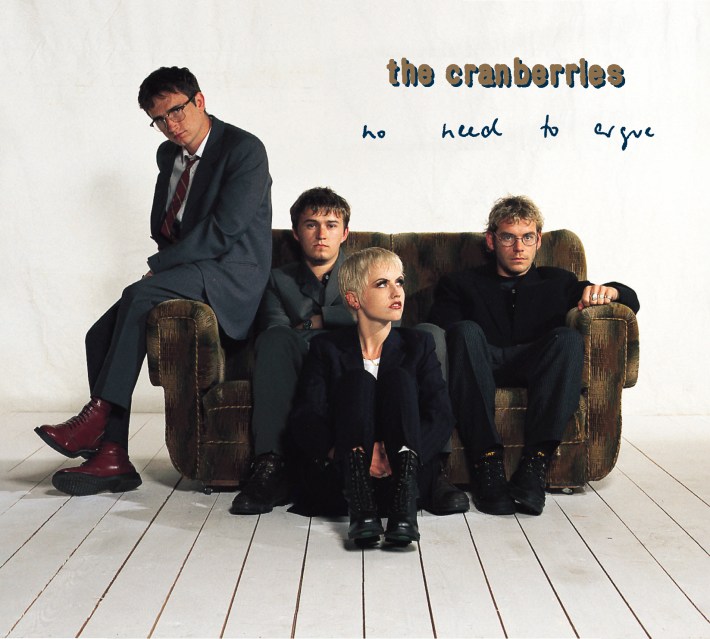

“I think people thought we were a political band, but we really weren’t,” Hogan tells me. “If you listen to our back catalogue, we mostly wrote about love, and relationships. ‘Zombie,’ and maybe only one or two others, are really the only songs that are even slightly political.” As bizarre as it must be to have such a misrepresentative song take off so rapidly, the live response to the song was so overwhelming, it eventually became the first single from the Cranberries’ second album, No Need To Argue, to be reissued Friday in an expanded and remastered double-disc edition.

‘The record label initially wasn't keen for a song with that subject matter to be the first single. But we knew how it was going down live,” Hogan tells me. Perhaps the vastness, the grandness of the chorus -- the emotional center of the song -- was the reason why the song managed to be such a huge, enduring hit, despite its political message. “It’s a song that has lived and lived,” Hogan tells me, without a hint of irony. “Not everyone gets the message, or really registers what the song is about. I do think it’s that huge chorus, and those huge vocals -- that really becomes the thing that everyone is going to focus on.”

If the musical and lyrical cues went over most people’s heads, the music video firmly roots the song in the Troubles. Directed by Samuel Bayer (“Smells Like Teen Spirit,” “Doll Parts”), the video was shot in war-torn Belfast, with bleak, grayscale footage of painfully young boys brandishing weapons and playing war games on the decimated cityscape, while British soldiers ominously patrol amongst the rubble. This documentary footage is cut with a highly stylised tableaux of O’Riordan, slathered in gold paint and surrounded by cherubs, half Joan of Arc, half Cleopatra. In one particularly startling moment, an image of a cherub threateningly aiming his bow is suddenly juxtaposed with a boy glaring at the camera, brandishing a stick, his face streaked in mud and his eyes glinting.

Hogan tells me how Bayer filmed the video: “When Bayer finished filming the band’s segment, he went up to Belfast, and spent the day wandering around and filming. He told the soldiers in the video that it was for a documentary he was making. Eventually he came clean.” Wasn’t it a bit of a risky move to lie to soldiers in what was essentially a war zone? “No, they were really excited. They were like, we’re going to be in a music video, that’s great!”

But what of the contemporary reception? Since its release in 1994, “Zombie” has been frequently covered (however misguidedly), maintaining a semi-regular rotation on X Factor and The Voice. A dreary cover by American hard rockers Bad Wolves, released in the wake of O’Riordan’s tragic death, did very well in the charts and has tallied more than 350 million YouTube views. Interestingly, the Bad Wolves cover tones down the Irishness of the lyrics significantly -- ‘It’s the same old theme in 2018,” vocalist Tommy Vext groans, updating the reference to the 1916 Easter Rising, and tweaking the references to “guns” in the chorus to the slightly more current “drones.”

The prize for my least favourite version of “Zombie,” however, has to go to Eminem’s noxious rework “In Your Head” from 2017’s Revival. On “In Your Head,” the “Zombie” chorus is lifted wholesale, functioning as little more than a blank canvas for Eminem’s solipsism: “I feel like a lame piece of shit/ I feel so cranky and bitter/ Cause when I look at me, I don’t see what they see/ I feel ashamed, greedy,” he raps dispassionately, lyrics that are so mawkish and diaristic, it is difficult to buy into the idea of even Eminem believing in them. It is a particularly muddled instance of a recurring pattern; of Eminem slotting samples of powerful female vocals into tracks which simply do not merit them, as an antidote to his lyrical acridity, and as an attempt at fast-tracking his way to emotional depth.

In even more recent years, “Zombie” has sporadically cropped up in TV shows as a kind of comedic shorthand for outsized Gen X angst. In The Office, Andy repeatedly sings the song, irritating his colleagues (offensively, actor Ed Helms recalls landing on “Zombie” after hours of brainstorming “annoying songs”). In the FX sitcom You’re The Worst, chaotic PR exec Gretchen (Aya Cash) howls the chorus during a post-breakup bender. And in whip-smart Irish comedy This Way Up, the similarly chaotic Ainé (Aisling Bea) and her straight-laced sister Shona (Sharon Horgan) are cajoled by their parents to perform an impassioned rendition of “Zombie” at a family party (“Sing the song about the ghosts!”).

To all who have watched #ThisWayUp, thank you SO much. It’s ALL out in America NOW on @hulu If you ARE American, have ever met an American or just have a baseball cap -we’d love if it if you could spread the word - we worked our FANNIES off making it (in both the UK & US) sense. pic.twitter.com/Q02jeSMhQm

— Aisling Bea (@WeeMissBea) August 23, 2019

It’s difficult to imagine another protest song being referenced so wryly. What is it about “Zombie” that makes it such a convenient comedic cue card? A large part of this could be the “huge chorus and vocals” Hogan mentioned -- and to be completely transparent, I’m no stranger to whipping out “Zombie” at karaoke.

One interesting subversion of the Cranberries' role in popular culture took place in the final scene of the first season of exemplary Troubles comedy Derry Girls. The film follows a tight-knit group of teenage girls as they grow up in Derry City during the 1990s. The scene itself is not comedic -- it is, in fact, quietly horrific: a blood-chilling juxtaposition between the teenagers dancing in a school talent contest, and news of a bombing flooding into their family living room. The scene is soundtracked by the Cranberries -- but the track chosen is “Dreams,” rather than the on-theme “Zombie.” The choice was so surprising that various tweets and news outlets misreported the track as “Zombie,” but “Dreams” was a shrewd choice, lending the scene a narcotised air, emulating the way time seems to slow and drift when something very, very bad has happened.

Like “Zombie,” the magic of the scene lies in how unflinching it is in the face of violence, the space it leaves us to feel the horror. The violence which inspired the song has (mostly) simmered down, with many attributing the end of the Troubles to the signing of The Good Friday Agreement in 1998. But a likely No Deal Brexit is set to cause constitutional chaos, and leaves Northern Ireland’s fragile peace hanging in the balance. Perhaps we should look back to the message of “Zombie,” and let ourselves be haunted once again.