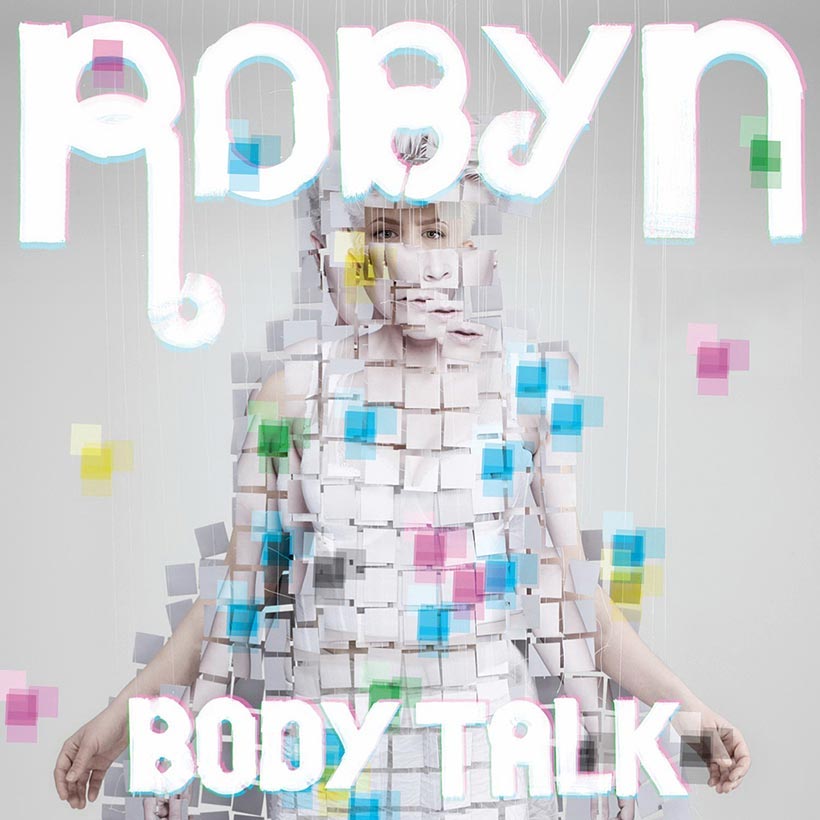

Body Talk: the pop album so good it had to be split into three parts. 2010 was a great year for fans of Robyn, the Swedish star who spent five years away before embarking on an ambitious year-long rollout of her fifth studio album, Body Talk, which culminated in the official release of the album 10 years ago this weekend. What would be overkill in almost anyone else's hands was a gift in hers. Body Talk is a staggering achievement that needed all that space to impact -- it's the defining work of Robyn's career, a pantheon-level pop album that presents a mutation of sentimental pop and mechanized dance music that would resonate through the rest of the decade.

Robyn was ahead of trend by releasing Body Talk in three distinct chunks, much in the same way she was ahead of trend when she released her 2005 self-titled album on her own independent label. She had been brought into the Interscope fold by the time Body Talk arrived, but her pragmatic streak remained. "I was thinking of a way to have a different work routine to fit my way of working rather than the release schedules the industry has," Robyn said in an interview to explain why she was putting out Body Talk as three separate mini-albums (effectively EPs) over the last half of 2010.

That continuous trickle of releases has become the norm for many pop stars as today's music climate has become geared towards the economy of streaming, an industry that was still nascent when Robyn made Body Talk. "It's a practical solution, not a conceptual idea," she said at the time. "Plus, people go on the internet and find the music they want. It's not about major labels pushing five records through the same channels and telling, 'This is what you should like this year.' As an artist, you look stupid if you don't recognize the new structure."

Body Talk was a successful experiment in harnessing the power of the internet to make Robyn into a figure that was less cultishly beloved (especially in the States) and more widely adored. Robyn was entering her 30s as Body Talk came out, but she had been in the music industry since her teens, both as a part of and fighting against the major label system. She had the perspective to deliver these songs with a full-throated enthusiasm, a youthful exuberance tempered by jaded adult regret.

Body Talk was a sensation, especially among indie tastemakers who back then still had a tenuous relationship with pop music that was this accessible. Led off by "Dancing On My Own" -- Stereogum's #1 song of the 2010s -- the entire year felt like the re-coronation of Robyn. She had naturally experienced much success and had scored bigger hits in the late '90s where the charts were concerned, but she'd never matched the pervasive impact some of these songs took on in the public consciousness. By the time the final release of Body Talk in November came around, it felt kind of perfunctory, if you can call a drop that included "Call Your Girlfriend" perfunctory. Robyn had already made the pop album of the year.

Body Talk Pt. 1 begins with "Don't Fucking Tell Me What To Do," a pulsating litany of everything that's bringing Robyn down these days, the crass collision of capitalism that crushes us all. Her phone, her email, these hours, her tour, this flight, her manager, her mother, her landlord, her boss -- they're all killing Robyn, causing her enough stress that she simply must insist: "Don't fucking tell me what to do." The pointed missive represents a break away from "With Every Heartbeat" and "Be Mine!," the biggest singles from her 2005 self-titled, which were defiant but still sounded hopeful that love might be just around the corner.

On Body Talk, Robyn was determined not to let heartbreak get her down anymore. She built herself up into a Terminator-like machine that can brush off reality like a bullet ricocheting off metal. "Fembot" finds her rebooting with a whole new operating system -- the song is an all-out assault in which Robyn is locked-in and loaded: "My system's in mint condition/ The power's up on my transistors/ Working fine, no glitches/ Plug me in and flip some switches." It's a persona that she would dismantle on 2018's Honey as she became introspective and slippery sweet, but the Robyn of Body Talk is mechanized for war, ready to fight off any heartache that might come her way.

That's easier said than done, and Body Talk is still filled with the synth-strewn heartbreak that Robyn made her name on. But there's a flippancy to her pain here -- it won't get the best of her now. "I'm gonna love you like I've never been hurt before/ I'm gonna love you like I'm indestructible," she sings on one track. Perspective is what drives Robyn this time around. On "Cry When You Get Older," she acts like some kind of time-traveling wizard who has experienced all the ways a heart can break and has come back to present-day to deliver an important message. She builds an actual time machine on "Time Machine," a way to go back and right the wrongs made in the heat of a moment.

As Robyn remakes herself into a better, more attuned human, she sings about the ways in which the technology can facilitate love and enhance heartbreak, how it underscores the loneliness we feel when we're theoretically more connected than ever. "I think it's a very common feeling these days that you're busy all the time and you're doing lots of things, but you're not being productive," she said in an interview. Body Talk is often concerned with the ways in which technology and humanity intersect, how our emotions are increasingly augmented by digital noise. Robyn's answer to that is to morph herself into a fembot that has feelings too. The way our bodies talk to each other is evolving, so we must evolve with it or be left behind.

The feeling of being an outsider courses through Body Talk. In her songs, Robyn positions herself as being on the outside looking in. On "Call Your Girlfriend," she's the other woman in a relationship, begging her lover to finally cut ties and runaway with her. But the narrative is left unresolved. The mood is celebratory but it's always something he should do; there’s no sense of any action having been taken. Body Talk thrives in those kinds of unresolved emotions -- when everything feels like it’s happening but you’re really just all alone in your room or out on the dance floor, swept up in the movement of bodies but not going anywhere. Robyn makes that stasis into a comfort.

"Lovesickness is the most extreme version of being an outsider or not feeling understood or loved," she said in an interview. "It’s a universal feeling everybody connects to." Her way of connecting with listeners is through heartbreak, a shared experience that can fuel our sadness into something that feels like community. "If your world should fall apart, there’s plenty of room inside my heart/ Just don’t include me out," she sings. That world includes the club, where Robyn thrives in both her music and her mind, spinning around in circles and inviting everyone else to spin out to oblivion with her. She recreates the dance floor in her own image, tries to bring people together as a way of making herself feel less alone. She succeeded here by turning heartbreak into a weapon, loneliness into a rallying cry. It's why Body Talk still works a decade later: Feeling alone is timeless.