You know the drill: The big line is coming up, so the DJ turns down the volume, and the whole crowd yells it. That's what's supposed to happen. That's not what happened in 2020.

Rap music is communal music. Always has been. In its earliest days, rap music was built on block parties and on electricity stolen from streetlights. A whole lot has changed since then, but the essence remains. Rap music will never sound better than it does when you're with a whole mob of your friends, at a party or in a club or at a festival, all of you shouting along with the lines you've heard hundreds of times. 2020 being 2020, that crucial experience has been taken away. Rap music still thrived and resonated this year. A lot of the best rap sounded like a commentary on present conditions, whether or not it was formulated that way. But the experience was different.

This year, the Grammys nominated five different middle-aged rappers for the Best Rap Album award. The youngest nominee was 35, the oldest 47. Worthy and popular music from younger artists was relegated to lesser categories. I objected, and yet I understand. The entire idea of the album has never been less relevant to young and playlist-savvy rap listeners. Many of this year's biggest and best rap songs didn't come from albums, or they came from expanded-edition addenda that merely served to challenge the notion of the album. Many of the best long-players did, in fact, come from rappers oldest enough to feel sentimental connections to the format.

For my money, 2020's best rap albums came from artists of all different ages and from all different corners of the genre map. (Some of the rappers on this list are more than twice as old as other artists on this list.) The best rap albums of 2020 didn't share a whole lot, but all of them have a purity of vision, a sense of self. Our best rappers are the ones who understand their strengths and know how to play to them. Not all of those strengths involve full-length albums, but we still got some good ones.

This list is entirely personal and subjective, based on my preferences and mine alone. (It doesn't necessarily overlap with Stereogum's list of the year's best albums, though I did help compile that, too.) Plenty of great 2020 rap albums aren't on this list, so here's where I'll make my apologies to 21 Savage and Metro Boomin, Sada Baby, Lil Uzi Vert, Open Mike Eagle, Megan Thee Stallion, Armand Hammer, Young Dolph, Jay Electroncia, R.A.P. Ferreira, City Girls, and the two Boldy James albums that aren't on this list, as well as plenty of others. Making a list of 10 great rap albums is a messy project, but 2020 was a messy year.

The star quality was immediately apparent. Pop Smoke was only 20, but he already rapped with grizzled authority, his elemental growl rumbling all over the guttural futurist beats. As a rapper, Pop Smoke loved the off-kilter bass-blobs of UK drill, a strange and unforgiving sound that not too many American rappers can possibly handle. He sounded like he was born for it. As a presence, though, Pop was pure New York, an imperious hustle-hard braggart. He headed for stardom, and he got there, but only after his own death. Twelve days after releasing his second mixtape, a casually excellent document of his rise, Pop was shot dead in Los Angeles. Pop's posthumous album Shoot For The Stars, Aim For The Moon positioned him for pop-rap stardom, but Meet The Woo 2 is one final portrait of a rising underground insurgent en route to takeover.

An old master goes on journeys, both internal and external, and documents bleary-eyed observations in meticulously fractured language. Aesop Rock's dense verbiage has been sending indie-rap devotees diving for dictionaries for more than two decades, but his latest opus is oddly approachable in its remoteness. Aesop styled Spirit World Field Guide as an astral-plane atlas, but the album's concept is simply the man's way of probing his own anxieties and insecurities from a fresh perspective. It's a solitary record. Aesop's voice is the only one we hear, and the psychedelic production — heavy on synth-drones and doom-metal basslines — is all him. But in telling his stories about trips to Thailand and Cambodia and Peru and the center of his own mind, Aesop is a garrulous, charismatic, often-funny host: "I look like a dick in my picture ID, but also the pic isn't me. Huh."

Finally, rap gets its very own version of Parker Posey at the beginning of Dazed & Confused, spraying ketchup all over the freshman girls and telling you to wipe that face off your head. The sneering Mobile, Alabama newcomer Flo Milli is an expert rapper in just about every way. She picks crispy, kinetic beats. Her rhythmic control is excellent. She writes sticky hooks that frequently reference songs that were classics when she was born. But more importantly, she's a character. Flo Milli delivers every punchline like she can't believe she has to explain how fly she is to someone as lame and embarrassing as you: "Everything I do irritate insecure bitches." That supremely bratty energy radiates through every track on Flo Milli's brief and catchy debut. She just showed up, and she already sounds like a star.

A decade ago, Long Island rapper/producer Roc Marciano figured out a winning formula: Meditative ambient post-boom-bap psychedelia, cut with detached and elegantly worded shit-talk. That epiphany birthed a whole verdant subgenre, one that probably accounts for half of this list. But even as his style found new converts, Marciano himself continued to refine his approach, developing his own insular musical language. Mt. Marci isn’t a cohesive statement of an album, and it won't tell you anything about the world. It's barely even a collection of songs. Instead, it's a sustained vibe, its samples expertly chopped and its funny, absurdist flexes spiraling off into beautiful insanity.

On a certain level, Alfredo sounds like an indolent, arrogant victory lap. After a whole career in and out of the major-label meat-grinder, Freddie Gibbs, a rapper of surpassing charisma and dexterity, has found his place in the world, rapping the absolute shit out of the prettiest loops from the prettiest loop-makers. The Alchemist's production on Alfredo is warm and soft and hazy, so even when Gibbs is dizzily piling up his cadences, he sounds like he's relaxing poolside. In Gibbs' lyrics, triumph and pessimism and gallows humor blur into each other, combining to form something like a worldview. He and Alchemist both sound like they're cruising, but cruising is what they do best. The success of Alfredo, Grammy nomination and all, stands as confirmation of what some of us have known for a long time: This motherfucker Freddie Gibbs can flat-out rap.

The Alchemist's twin 2020 opuses are opposite sides of the same coin. For both albums, the veteran producer went long with long-tenured, Midwestern-born underground-rap fundamentalists with criminal histories and bone-hard baritones. Whenever Boldy James and Freddie Gibbs team up, which they do pretty often, they must feel like Spider-Man clones pointing at each other. But where Gibbs luxuriates in ill-gotten spoils, James meditates on the costs. The Price Of Tea In China is a bleak chronicle of the anxiety and paranoia and heartbreak of a life spent in the underworld: "My son think that I don't love him; he don't know his daddy thugging." Alchemist surrounds James' wizened husk of a voice with minor-key pianos and ominous clouds of bass — a fitting soundtrack for American tragedy.

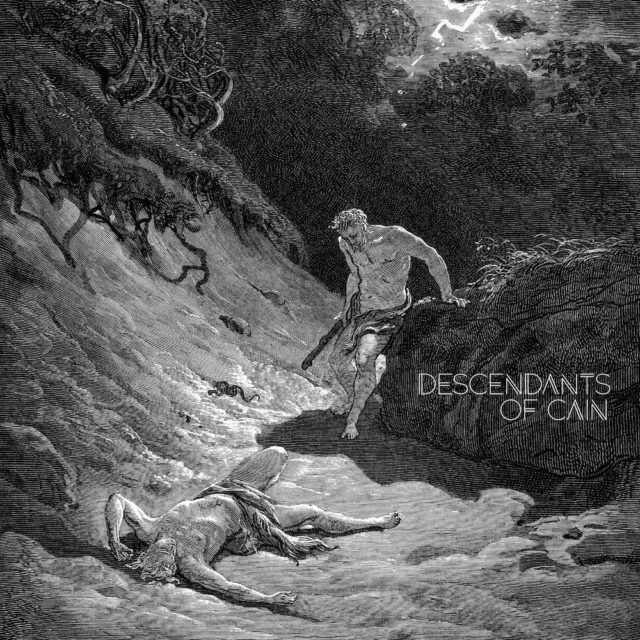

Note that the word in the title is Cain, not Caine. Ka isn't talking about the powdered stimulant that his historically fueled so many rap narratives, though the double-meaning is probably intentional. Instead, he's talking about Cain, the Genesis brother-murderer. People have been calling Ka "monastic" so long that it's only fitting for him to finally record a full concept album charged with Biblical imagery. Ka, the wise and quiet Brooklyn fire chief and DIY shadow-rap auteur, uses the Old Testament as philosophical architecture, a frame to help illustrate the inhumanity of American structural racism and the violence that comes out of it. Ka's mutter has never been heavier, and his words have never cut deeper. You don't need to believe in any particular religion to hear something mystical in these teachings.

Traditionally, rap's biggest stars are vivid and outlandish personalities, glittering Hollywood idols who make you feel lucky to bask in their presence. This is not Lil Baby. Instead, Lil Baby is an insular figure, a melancholic melodic mutterer whose singsong croak carries bluesy weight even when he's at his most triumphant. He leans into beats that sound like broken music boxes, and his hypnotic lamentations often come across as ritual incantations. Baby never carries himself like he should be strutting onto arena stages amidst pyrotechnic spark-showers, and yet he's now unquestionably the biggest star in rap. My Turn, his new album, is 2020's biggest LP in any genre, and Baby's voice was a constant presence through the year, the slippery thud of "We Paid" seeming to come from every third car window over the summer. Maybe Lil Baby is just the man for his moment. My Turn arrived just before COVID, and its sad and sleepy pleasures worked as comfort and consolation.

There's something so beautiful about seeing two rap lifers abandon all pretense at relevance and somehow coming out with the most relevant shit imaginable. For their fourth album as a duo, Killer Mike and El-P, both of whom had left rap's zeitgeist in their rearviews long ago, made a raging, anarchic, joyous love letter to rap history, to Public Enemy and Gang Starr and Smoothe Da Hustler. On RTJ4, Mike and El rage as hard against entrenched life-sucking power structures as they ever have, but they do it with a sense of hard-fought euphoric camaraderie. They turn it into a party, inviting grown-ass rebels from across the musical landscape — 2 Chainz and Josh Homme and Pharrell and Zack De La Rocha and Gangsta Boo and DJ Premier and Mavis Staples and not one single person under the age of 40. But this old-timers' moshpit came out into the twin apocalypses of viral plagues and rioting cops, and it hit like an adrenaline needle to the heart. May we all age so noisily.

Detroit hardass Boldy James had one of the greatest rap years in recent memory: Four albums, each recorded with a single producer, each great. But the best of those albums — the best rap album of the year — was the one that James mostly recorded more than a decade ago, back before anyone outside his neighborhood knew his name. Sterling Toles, the first producer ever to record James' voice, took verses that he recorded between 2007 and 2010, and he spent years tinkering and layering. Working with Detroit musicians young and old, Toles took those Boldy James verses and surrounded them with DIY splendor: horns, choirs, synths, strings. The end result is an offering on the altar of afro-futurist maximalism, a woozy psychedelic pile-up of soul and jazz and electro-funk that makes good on all its considerable ambitions. And thanks to James' old recordings — hardbitten, emotionally direct, haggard before their time — all those beautiful fripperies work to support a beating human heart, a diamond of a pure rap voice. Manger On McNichols is a starry-eyed labor of love, a utopian work born out of a cold and hard place.