August 2, 1986

- STAYED AT #1:2 Weeks

In The Number Ones, I'm reviewing every single #1 single in the history of the Billboard Hot 100, starting with the chart's beginning, in 1958, and working my way up into the present.

The 1984 movie The Karate Kid is a product of its time, and nobody would ever mistake it for anything other than an extremely 1984 movie. But it's also a film that persistently refuses to get old. The Karate Kid is an expertly-told variation on the Rocky fairy tale -- a scrawny little kid, displaced from New Jersey to California, falls for a bully's girlfriend and gets beat up for it. The old Japanese man who works as super in the kid's building takes him under his wing, slowly teaching him discipline and self-respect. The kid comes out of nowhere to beat the bully and the bully's entire sociopathic dojo at a regional karate tournament, and his final triumph feels as mythic as it is unlikely.

John G. Avidsen, director of the original Rocky, made The Karate Kid, and it went on to become a huge hit, one of the biggest movies of 1984. The Karate Kid's first sequel did even better. Coming out in the summer of 1986, The Karate Kid, Part II earned $115 million at the domestic box office -- $25 million more than the first movie had made. On the year-end 1986 box-office chart, The Karate Kid, Part II comes in at #4, just below Platoon and just above Star Trek IV: The Voyage Home. (Weird year.)

Unfortunately, The Karate Kid, Part II pretty much sucked. Avidsen moved the action from California to Japan, half-assedly coming up with narrative reasons for Ralph Macchio's young Daniel to cross the ocean with Pat Morita's Mr. Miyagi. In Japan, they pretty much replay the first movie's narrative, adding in some orientalist touches that have aged badly and somehow making Daniel into a way-more-irritating character. Cobra Kai, the extremely entertaining Netflix hit that serves as a decades-later Karate Kid sequel, has wisely avoided really acknowledging the existence of The Karate Kit, Part II, focusing instead on the still-fun central conflict of the original movie. Nobody needs to remember Part II.

Part II was a bigger movie with a bigger soundtrack, but it was shittier in every way, soundtrack included. The song that everyone associates with The Karate Kid is "You're The Best," the howling anthem sung by former Brooklyn Dreams member and Donna Summer collaborator Joe Esposito. (Esposito later admitted that "You're The Best" had been rejected from the soundtracks of both Rocky III and Flashdance.) But "You're The Best" wasn't a hit in its time. Instead, the hit from The Karate Kid was Bananarama's immortal new wave classic "Cruel Summer." ("Cruel Summer" peaked at #9. It's a 10.)

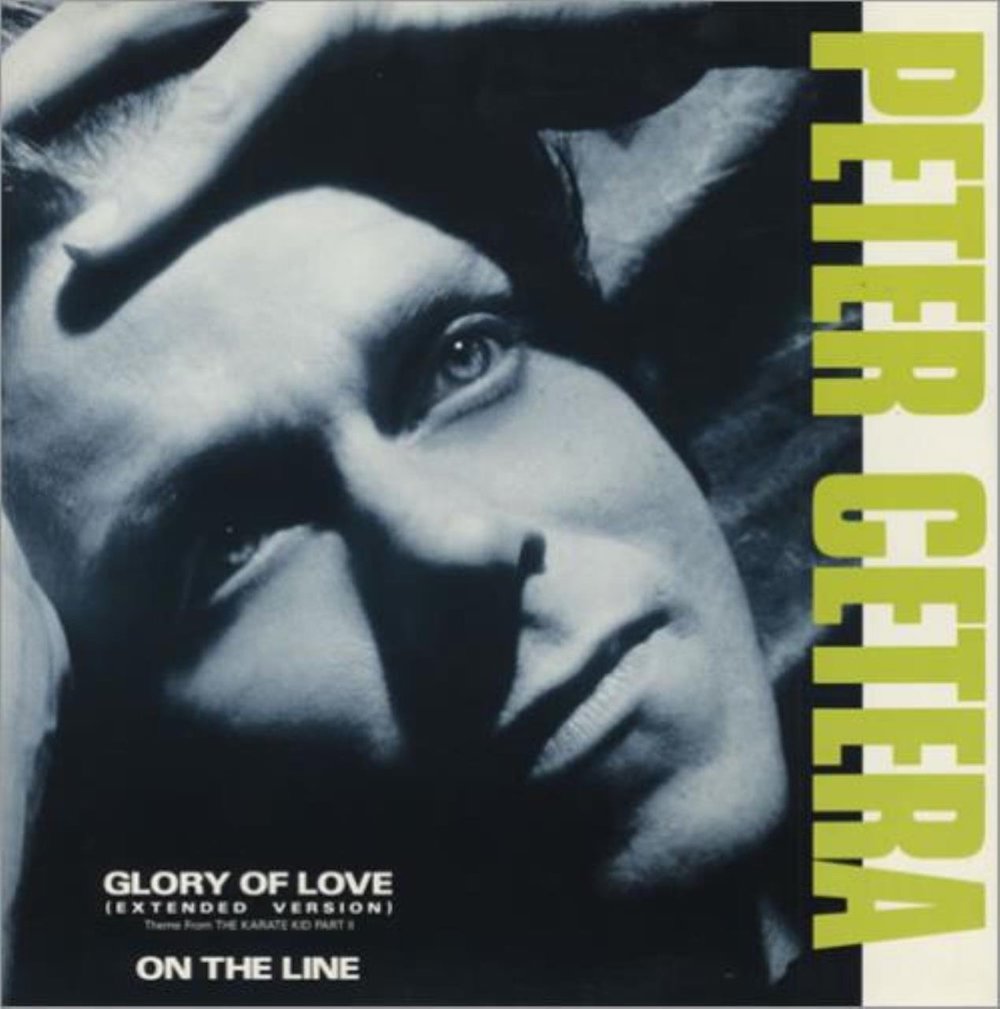

The Karate Kid, Part II didn't have anything on the level of "Cruel Summer." Instead, the big theme from Part II was "Glory Of Love," the screaming ballad that the former Chicago member Peter Cetera recorded immediately after leaving the band. In grand Karate Kid tradition, "Glory Of Love" was another Rocky-franchise reject. Cetera had submitted "Glory Of Love" for the soundtrack of the 1985 smash Rocky IV, and the producers had rejected it. A few weeks later, "Glory Of Love" found its way to the Karate Kid people and found its home.

Before he made "Glory Of Love," Cetera had spent 18 years in Chicago, a band that wasn't supposed to have a frontman. A 23-year-old Cetera had joined the Chicago Transit Authority as singer and bassist in 1967. This was a group where lead-vocal and songwriting duties floated around and where nobody posed for album-cover photos. They were a brand as much as a band, and they were fantastically successful at it, selling tons of records. But eventually, Cetera, with his toothy smile and yowly voice and propensity for power ballads, started to emerge from the mass of the band. When Chicago first hit #1, they did it with "If You Leave Me Now," a slow-dance song that Cetera wrote and sang. Pretty soon, it became obvious that most of the band's biggest hits were the Cetera ballads. That didn't sit too well with the rest of the band.

On their 1982 album Chicago 16, Chicago ditched their longtime producer and manager James William Guercio, working instead with the rising corporate-pop savant David Foster. For much of that album, Foster used studio musicians like the members of Toto, sidelining the actual members of Chicago. That album's big single was another Cetera ballad, "Hard To Say I'm Sorry," and it once again hit #1.

Cetera had tried to break out from Chicago once before. In 1981, Cetera had released a self-titled solo album, and it had gone nowhere. Cetera has long blamed Warner Bros. for the album's failure. To hear Cetera tell it, Warner didn't want to hurt Chicago's momentum, so they didn't promote the album. A few years later, after the success "Hard To Say I'm Sorry," Cetera wanted to make another solo record. He wanted to do something like what Phil Collins had done with Genesis -- splitting his time evenly between his main band and his solo career. The rest of Chicago weren't on board with it. They and their management told Cetera that he was out of the band if he didn't keep up with the group's touring responsibilities. So Cetera left Chicago. It was not an amicable parting.

Cetera wrote "Glory Of Love" with his "Hard To Say I'm Sorry" collaborator David Foster and with Diane Nini, his wife at the time. Cetera had gotten stuck while working on the song, so Nini had helped him figure out how to finish it. Cetera recorded it with Michael Omartian, the veteran producer who'd worked on both of Christopher Cross' #1 hits. It's a polished, professional pop product, and it mostly sounds like ass.

The production of "Glory Of Love" is all the excesses of big-money mid-'80s studio pop crammed into one shitty package. It's got the expensive synth hums, the frictionless guitar crunches, the gloopy electric-piano runs. It's got tootling synth-horns, which pissed off Cetera's ex-bandmates in Chicago. (They thought he was ripping off their sound with those horns.) Cetera sings the whole song in an unpleasant upper-register howl. It's a power ballad with no power, a pure product. In that way, it fits right in with its movie.

"Glory Of Love" is a love song in only the dumbest and most obvious ways. Cetera wails that he's a man who will fight for your honor, that he'll be the hero that you're dreaming of. Beyond some perfunctory lines about how Cetera's narrator sometimes says things he regrets, the song never acknowledges the complexities of growing together with another person. Instead, Cetera's narrator sounds like a guy who knows he's fucking up but who only knows how to promise vague clichés: "It's like a knight in shining armor from a long time ago/ Just in time, I will save the day/ Take you to my castle far away." This might work if Cetera was the least bit self-aware about any of this, but Cetera doesn't sound like he's writing from the perspective of a dumb-boyfriend character. He just sounds like a dumb boyfriend.

"Glory Of Love" is not entirely charmless. The chorus sticks, and it's the kind of thing that might be fun to sing at karaoke. Also, I like the extremely goofy jazz-cat dance shuffle-dance thing that Cetera does in the karate dojo at the end of the video. None of that is enough to make "Glory Of Love" work as anything other than a rote, boring, obvious wet fart of a song. It's exactly the kind of thing that we can leave in 1986.

"Glory Of Love" kicked off a successful run for Cetera. Three days after The Karate Kid, Part II opened in theaters, Cetera released his hilariously titled solo album Solitude/Solitaire, which eventually went platinum. Cetera will appear in this column again. So will David Foster and Michael Omartian. For that matter, so will Chicago.

GRADE: 3/10

BONUS BEATS: New Found Glory sure like recording pop-punk covers of songs from '80s movies. Here's the version of "Glory Of Love" that the band released in 2000:

(New Found Glory's highest-charting single, 2002's "My Friends Over You," peaked at #85.)