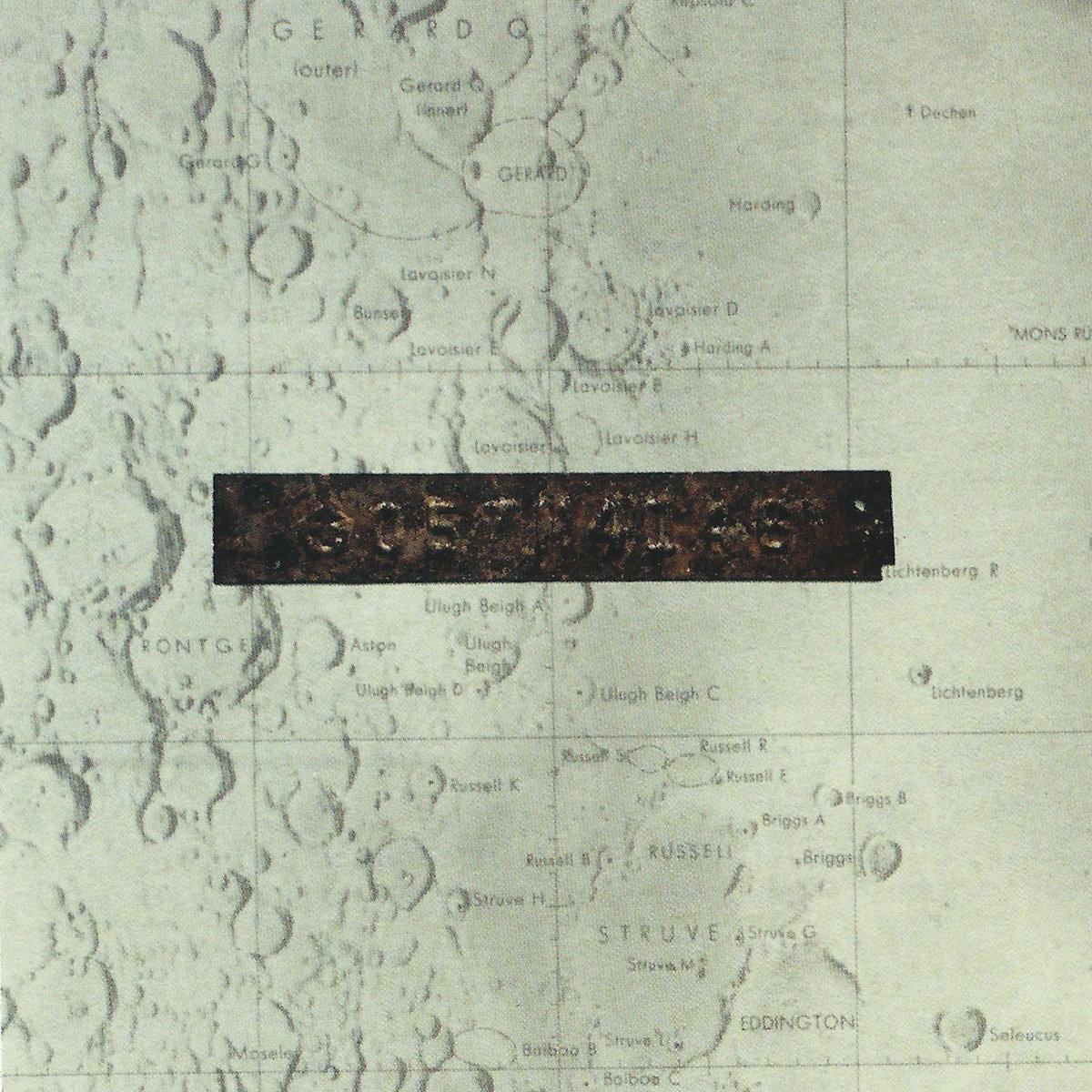

For a band whose sound was built on the idea of being so quiet you're almost invisible, Low was remarkably prolific in their first decade -- it's almost as if they made up for in quantity what they purposely lacked in volume. Things We Lost In The Fire, which turns 20 years old today, was their fifth full-length in just seven years, and that's not even counting three album-length EPs that also came out between 1994 and 2001: Transmission, Songs For A Dead Pilot, and their beloved Christmas collection.

With all of those deliciously slow records to choose from -- not to mention a further seven studio albums, various side projects, and assorted other releases since -- it's almost easier to digest Low in terms of eras, which are even sort of neatly divided. On their first three albums, all for the major-backed indie label Vernon Yard (long deceased, but known at the time as the US home of the Verve), the Duluth trio defined and refined their early mission, which was to play as slowly and quietly as possible. So 1994's I Could Live In Hope, 1995's Long Division, and 1996's The Curtain Hits The Cast share that vibe, a series of slow builds that never even threaten much release. Each one is beautiful, though for the most part difficult for the non-fan to distinguish from the others. They're all marked by a sort of distanced sadness and lots of reverb: Singers Mimi Parker and Alan Sparhawk were as restrained as you might expect a married couple from Duluth, Minnesota to be -- there was plenty happening below that forlorn surface, clearly, but they weren’t about to shove it in your face.

And while it'd be inaccurate to say that a flip was switched when Low moved over to the Chicago indie label Kranky for albums four through six, something noticeable clearly happened. Starting with 1999's Secret Name, everything got a lot more dry, sonically speaking -- no surprise given that Steve Albini recorded both that album and Things We Lost In The Fire. But just as important as that expanding sonic palette was an emotional widening. These three records -- the band's strongest stretch of albums in a remarkably strong catalog -- brought more joy and release, but also more menace. The sadness on those first records was often pretty and hopeful, but for this stretch Low got darker and lighter, sometimes all at once.

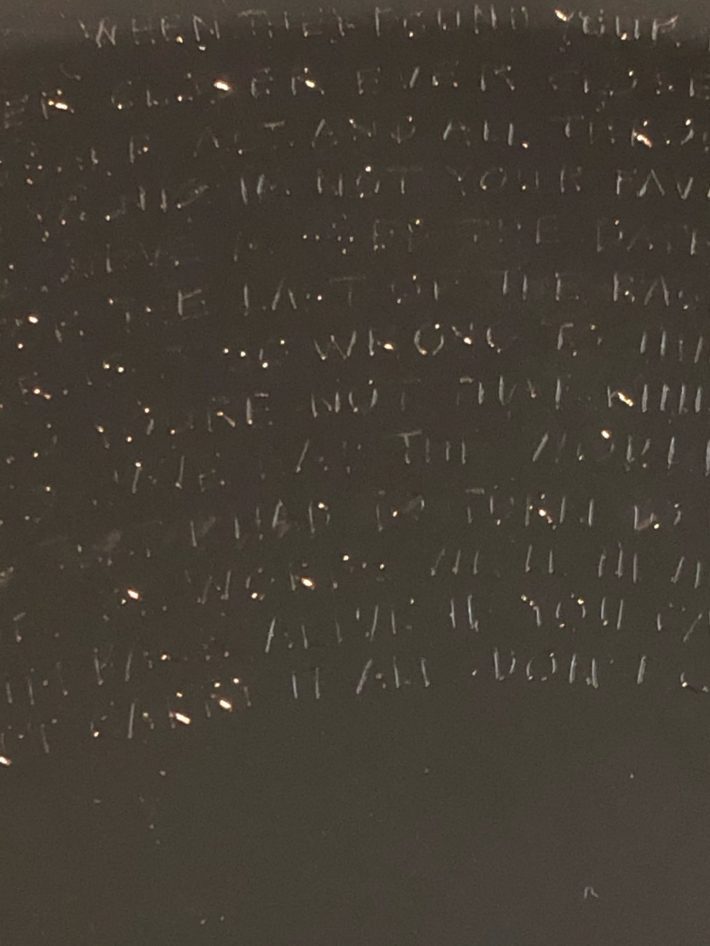

Nowhere is that more apparent than on "Sunflowers," the opening track on Things We Lost. The guitars strum, the drums have the pulse of a living being, and the refrain begs for a singalong: "Sweet, sweet, sweet/ Sweet sunflowers." Sparhawk even gives a delightful little off-the-cuff "hup!" before the song marches to its rising, dare I say triumphant outro. But listen closely to the song's first words, and you’ll reckon that all is still not exactly right: "When they found your body/ Giant X's on your eyes." The album's other crowd pleaser is "Dinosaur Act" -- another gorgeous, crashing chorus with wistful lyrical undertones and even a glorious trumpet line that follows the vocal melody (played, oddly enough, by Albini's Shellac bandmate Bob Weston). But Things We Lost In The Fire balances out those bigger moments with some of the band's most spare and slightly scary. Right between "Sunflowers" and "Dinosaur Act" sits "Whitetail," whose insistent, unchanging guitar suggests something sneaking up on you, intent on doing you harm. The lyrics, consisting of maybe 20 words, menace as well: "Closer, closer/ Ever closer."

Throughout the Low catalog, Parker and Sparhawk share vocals: Sometimes she's in front, sometimes he is, and often their voices wind around each other's -- hers more sympathetic and longing, his more direct, but always gorgeous. She takes the wheel for Things' midsection; "Laser Beam" is nothing but her near-whisper and a simple guitar line, and just two songs later she builds from resignation to crushing bravado on "Embrace." On the latter she's accompanied by subdued strings, another step away from Low's original minimal mission. It's not particularly clear what "Embrace" is about -- the same is true of most of Low's lyrically impressionistic catalog -- but I've always read it as a companion to the final song on Things We Lost In The Fire, "In Metal." "Embrace" includes the early lyric "Pushing my body/ To get that embrace" and ends with, "He handed me your head," which I've always read as a reference to childbirth.

That would directly connect it to the stunning "In Metal." Preceded by an untitled bit of palate-cleansing noise, "In Metal" is one of Low's best songs, and one of a few in their vast catalog that's relatively straightforward lyrically. It's about the birth of Parker and Sparhawk's daughter Hollis, and rather than a simple declaration of parental joy, it's an emotional examination -- a slightly painful nostalgia for something that hasn't even happened yet, their child growing up. "Partly hate to see you grow," Parker sings, "And just like your baby shoes/ Wish I could keep your little body/ In metal." Hollis herself squeaks in delight as the song begins. It got me well before I was a parent, and gets me even more as the father of a 10-year-old. "In Metal" ends this emotionally complex set of songs on a joyful note, and the last thing you hear is a little baby coo. Things are going to be all right, it seems to say, even if they're rarely easy.

If it's not obvious by this point, I’m an unabashed Low fan -- if I were younger I might even use the word "stan." I could probably write an Anniversary column on pretty much any of their records: Trust, just a year after Things We Lost In The Fire, is so rich and so similar, yet worlds apart. Drums And Guns, their second for Sub Pop -- which has released everything in the post-Kranky years -- is snarly and confrontational. Double Negative, the massively praised experimental-leaning set from 2018, pushed them in entirely new directions. Though it got some of the best reviews of the band’s career, Things We Lost In The Fire wasn't a watershed moment in terms of commercial success or visibility. Low's career has seemed to move as slowly and steadily as their music, blissfully content to exist outside any scene.

I feel lucky to have watched Low evolve since the beginning: I wrote what I'm pretty sure was one of the first reviews of I Could Live In Hope back in 1994 for a fanzine I published, after which I got a delightfully polite answering-machine message from Alan Sparhawk, thanking me for taking the time to listen. In the sea of cantankerous, detached '90s indie-rock — which I also loved, don't get me wrong -- how could the quietest, most beautiful band around not stand out?

I've seen Low play probably 50 times, from a campus coffee shop in Beloit, Wisconsin to a funny little chapel in Madison to dingy rock clubs to beautiful theaters, from 10 people in the audience to 10,000. It's special no matter what they choose to play on a given night, though my heart skips an extra beat when anything from Things We Lost In The Fire (or its two chronological neighbors, Secret Name and Trust) make its way onto the set list. Twenty years and several musical leaps later, it burns brighter than ever.