"The Blue Album" made Weezer famous. Released just over a month after Kurt Cobain's death, the band's self-titled debut presented a brighter, nerdier, more earnest form of "alternative rock," one swearing allegiance to KISS and Dungeons & Dragons and produced by power-pop master Ric Ocasek. Weezer boasted the sludgy power chords familiar to grunge fans, but none of the tortured mystique. Instead, right there on the cover were four schlubs making no effort to present as cool, whose odes to surfing and Happy Days had more to do with Boomer nostalgia than scathing Gen X irony. Their leader, Rivers Cuomo, was raised at the Rochester Zen Center and an ashram in Connecticut, yet these were not deep spiritual meditations. They were magnificently catchy, meticulously orchestrated, hard-hitting rock songs that appealed directly to hapless teenage boys who knew they could never be Kurt Cobain. Sometimes they dealt in gleeful absurdities built for shouting along, like the hip-hop slang that led off "Buddy Holly" (still a novel idea at the time) or the timeless refrain, "If you want to destroy my sweater/ Hold this thread as I walk away!" More often, they dealt in wide-eyed romantic fantasies that easily curdled into toxic possessiveness. Despite some lyrical landmines of that ilk, it's rightfully remembered as a masterpiece.

The following year, Cobain's old drummer Dave Grohl emerged with a new solo project called Foo Fighters. He'd recorded every instrument on the self-titled debut album himself -- an impressive feat, but not nearly as impressive as the songwriting. From the singles to the deep cuts, Foo Fighters was stacked with songs far too colorfully immediate to be the private demos Grohl had imagined. Where the defiant In Utero had served up the rawest, ugliest version of Nirvana, Foo Fighters steered grunge's loud-quiet-loud formula into full-blown pop songs. Grohl's pedigree, his penchant for piercing screams, and his blisteringly aggressive drumming lent Foo Fighters a certain edge unattainable to the likes of Weezer. But he was also a total goofball, as exemplified by the "Big Me" video's hokey parody of a Mentos commercial. He could be light and playful, as on the swinging "For All The Cows," and he could just as easily descend into a dense, moody swirl like "X-Static." From the anthemic "This Is A Call" to the brisk "Good Grief" to the self-explanatory "Floaty," Grohl was slinging hooks too sticky to write Foo Fighters off as a vanity project. The man wasn't kidding when he shouted, "I'll stick around!"

In 1996, Weezer returned with Pinkerton, a wounded and explosive document that blew out the sounds and sentiments of "The Blue Album" to uncomfortable extremes. Reeling from a bad breakup that brought him face to face with his own worst qualities, Cuomo traded feigned innocence and studio-sculpted bombast for guilt-ridden despair and unkempt feedback. Even the quirkiness was now jarring, be it Cuomo declaring, "God damn you half-Japanese girls/ You do it to me every time!" on the nervous-wreck pub sing-along "El Scorcho" or lamenting, "I'm dumb, she's a lesbian!" on "Pink Triangle." Endless meaningless sex, allusions to physical abuse, a creepy transcontinental flirtation with a teenage girl: This was a much darker trip than many Weezer fans had signed up for. Pinkerton was thus greeted with widespread disappointment at first, dismissed as an inaccessible sophomore slump. But by the end of the decade it had been reclaimed as a cult classic, an album so intensely beloved that fans were begging Weezer to perform it.

No such detours plagued the second Foo Fighters album. By 1997's The Colour And The Shape, Grohl had recruited bandmates and shifted to impeccable studio recordings. It was at times gentler (there were actual ballads like "Doll" and "February Stars"), yet rockers like "Wind Up" and "Enough Space" were arguably more ferocious than anything on the debut, owing partially to a pristine clarity honed with Pixies producer Gil Norton. It all sounded professional in the best way: the melodies laser-focused, the rhythms sharp and pummeling, everything optimized for maximum impact. In keeping with that blockbuster approach, the album's singles were miniature epics -- the spring-loaded rager "Monkey Wrench," the awestruck everyman tribute "My Hero," and especially the revved-up power ballad "Everlong," which boasted a brilliantly surreal Michel Gondry music video and quickly became the band's signature song.

By this point Foo Fighters were royalty at my suburban Ohio middle school, particularly among those of us who dicked around with guitars in our free time. Weezer were similarly revered, and within a few years, as the legend of Pinkerton took hold, they developed an even more sterling reputation. These early records from both groups would prove to be some of the most enduring documents of that mid-'90s moment when alt-rock went pop: bashed-out adrenaline rush music with melody to spare. Even as I worked my way through more virtuosic guitar music from Metallica to Jimi Hendrix, uglier and more aggressive sounds from the nu-metal universe, and, eventually, the cooler and more obscure world of indie rock and beyond, my love for Weezer and Foo Fighters remained.

For me and millions more like me, the brand loyalty was strong -- and over the next couple decades, both bands would put that loyalty to the test repeatedly. The Foos began a slow decline into mediocrity with 1999's There Is Nothing Left To Lose -- a completely fine album from a band once capable of much better than "fine" -- and eventually became the go-to rock stars for awards-show performances, documentary interviews, and such. In 2001, Weezer returned from their long post-Pinkerton hiatus with "The Green Album," a soulless facsimile of their "Blue Album" sound that nonetheless feels like a minor classic compared to what followed. And what followed was a lot. Give Grohl and Cuomo this much: They've been persistent. Among their mid-'90s rock-star peers, only Billy Corgan has kept releasing music at such a steady clip, and even he had to restrict himself to pre-2000 music to headline arenas again. Weezer and Foo Fighters, meanwhile, have each essentially ridden the goodwill from their first two albums into something approaching elder statesman status, never mind that they've never scraped such heights since.

It's not that Weezer and Foo Fighters never released any more good music after 1997. Each band's catalog is speckled with bangers. Foo Fighters settled in as workmanlike rock radio mainstays, good for one or two solid singles per album; they assembled a respectable Greatest Hits album in 2009, albeit one that weirdly excluded MTV staple "I'll Stick Around." Weezer could easily put together a similar disc, though I'm not sure an album of their biggest hits and a career-spanning overview of their best tracks would be the same album. Their run has been spottier, with higher highs than the Foo Fighters have managed but much lower lows as well. Sometimes, as with their highest-charting single "Beverly Hills," their most craven instincts have been rewarded. When they've come closest to recapturing their former glory, as on 2014's Everything Will Be Alright In The End, it has generally not paid off, commercially speaking. My esteemed former colleague Michael Nelson summed up their decline succinctly in his review of the aforementioned EWBAITE:

Yes, the Rivers Cuomo who made the "Blue Album" and Pinkerton was a deeply fucked-up person, but the art he produced addressing and wrestling with those issues was undeniable. I’m talking about everything else, starting with the robotic, dispassionate "Green Album," followed by the uneven and willfully difficult Maladroit. And those were relative high points! After that, things got ugly: 2005's Make Believe and 2008’s "Red Album" were introduced, respectively, by the singles "Beverly Hills" and "Pork And Beans" — utterly reprehensible, indefensible trash polluting albums whose most enthusiastic defenses never rose beyond "not as bad as everyone says" and "occasionally interesting." By the time they got to Raditude, the Weezer brand was already badly devalued. That album didn’t come as much of a surprise or even a disappointment — Weezer were already a creepy, hollow simulacrum of a once-great band.

Things have been just as wobbly for Cuomo in the ensuing decade. Weezer were kind of raging there for a few years, recovering some of that hard-charging joie de vivre and dialing back the cringe-inducing lyrics a smidge. But the later 2010s saw them kicking out a string of mostly unmemorable, occasionally egregious records. Lifelong fans like me will sometimes talk ourselves into the band's late-career dispatches, always with the qualifier that the music doesn't touch what Weezer used to be. To their credit, they were savvy enough to cover Toto's "Africa" at the urging of a teenager in Ohio, which became their biggest hit in years, spawned a whole covers album, and probably convinced a bunch of apostate fans to tune back in. And now they've embarked on a series of themed albums that seem at least marginally more interesting than something like the insipid Pacific Daydream.

It began last Friday with OK Human, on which Cuomo attempts to spice up the Weezer formula by writing on piano, dispensing with digital technology, and applying full-fledged orchestral arrangements to his songs. It's often quite pretty and sometimes borders on powerful, be it Cuomo exclaiming, "I don't know what's wrong with me!" on the bittersweet opener "All My Favorite Songs" or the lush string parts that envelop "Bird With A Broken Wing." Yet despite the organic approach, as with most of Weezer's post-Y2K material, these songs still sound like product first and foremost. It's not outright bad, just largely unremarkable. It doesn't help that he's paired this music with hyper-literal lyrics about pandemic life, like this passage from "Playing My Piano" that doesn't even rhyme: "My wife is upstairs, my kids are upstairs/ And I haven't washed my hair in three weeks/ I should get back to these Zoom interviews/ But I get so absorbed and time flies." It's an album easy to appreciate but frustratingly hard to love -- a familiar story where Weezer is concerned.

OK Human is the first of many genre exercises on the horizon. Weezer will follow it later this year with Van Weezer, the hard-rocking album they planned to drop last year ahead of their COVID-postponed Hell Mega Tour with Green Day and Fall Out Boy. That tour is tentatively supposed to launch in July -- we'll see! -- but whether or not Cuomo hits the road, he clearly has no shortage of ideas about how to fill his time. In an interview this week, he was already sketching out a series of subsequent Weezer albums exploring disparate stylistic pathways: "The next idea is a four album set, where each album is corresponds to one of the four seasons," he explained, "and then each album has a very different vibe and lyrical theme." His seasonal themes included a breezy "Island In The Sun" vibe for spring, Franz Ferdinand-style dance-rock for fall, an Elliott Smith-inspired '90s singer-songwriter record for winter. "So yeah, there's just always new things you can try."

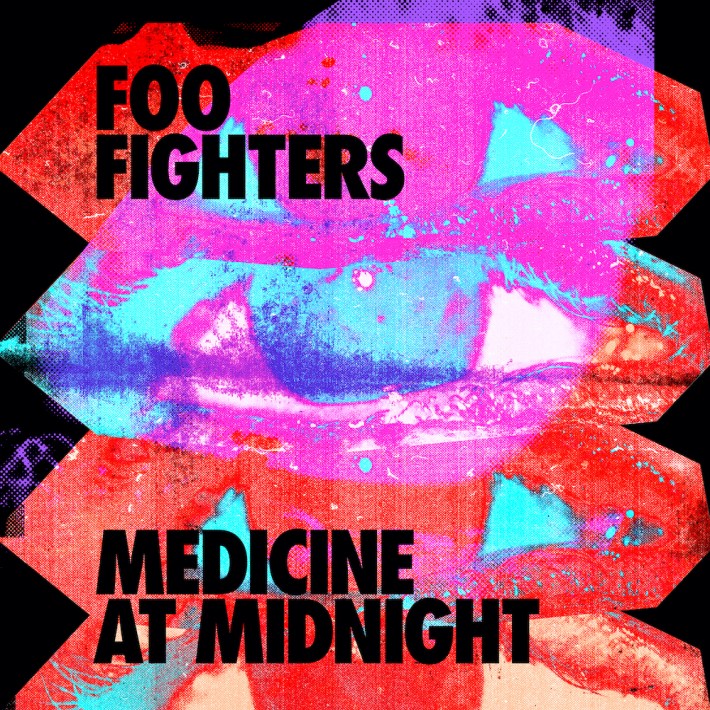

A similar impulse animates Foo Fighters today. "That’s one of those things that I think of every morning when I wake up," Grohl recently told the New York Times. “What have we not done? What could we do today?" This restless search is how they ended up making Medicine At Midnight, their new album arriving this Friday. This one is supposedly the inevitable dance record every rock band gets around to eventually, even living embodiments of "RAWK" like the Foo Fighters. Grohl has compared it to Abba (an old Cobain favorite) and David Bowie's Let's Dance (Omar Hakim, a drummer who played on Let's Dance, appears on multiple tracks). "I started thinking about tempos and grooves and rhythms and keeping the big choruses that we’ve always had, but framing them in a way that it’s not 200 beats per minute and screaming bloody murder," he told the NYT.

The talk of a dance influence is a bit overstated. Lead single "Shame Shame" rides a slow, clattering groove; "Cloudspotter" boasts funky guitar and abundant cowbell; "Holding Poison" rocks a dance-punk beat; there's quite a bit of rhythmic action on "Medicine At Midnight"; opener "Making A Fire" is enlivened by choral "na na na" backing vocals. They made a noble effort to mix things up here, and the result is another somewhat engaging, occasionally rollicking entry in their catalog. Yet even the danciest songs mostly blur into standard-issue Foo Fighters guitar churns with big howling Grohl choruses, and the rest of the album basically could have appeared on any Foos album since the second George W. Bush administration.

This isn't the first Foo Fighters album concept that has more or less melted away into the same old poppy hard rock record. Their 2005 double album In Your Honor was split into one electric disc, one acoustic -- probably the most basic self-imposed structure in the book. The follow-up, 2007's Echoes, Silence, Patience & Grace, took the radical step of putting the electric and acoustic tracks on the same album. For 2011's Wasting Light, they went all analog with Nevermind producer Butch Vig and continued to sound like Foo Fighters. For 2014's Sonic Highways they recorded at various famous studios around the country, again with Vig in tow, and it turned out Foo Fighters sound like Foo Fighters no matter where they are geographically situated. 2017's Concrete And Gold saw them switching out Vig for Greg Kurstin, the former Beck keyboardist who has evolved into a big-time pop hit-maker. You will not be surprised to learn that it still sounded like a Foo Fighters album.

At this point these bands are who they are -- and who they are is a sterile approximation of who they used to be. Neither OK Human or Medicine At Midnight is an embarrassing effort, they're just the latest in a long line of inessential releases. It's hard to imagine anyone developing an intense personal connection to these albums besides those still holding on to Weezer and Foo Fighters out of inertia. Each band has its diehard fans who swear their heroes' creative output continues to be as vital as ever, people who presumably prize the comfort of a familiar brand over inspired music that sets your life on fire. But a good portion of the attention afforded to Weezer and Foo Fighters, I'd wager, comes from people like me who will keep checking on these bands in perpetuity no matter how many times they leave us shrugging. I never understood why Boomers bothered with late-career Rolling Stones albums that basically served as excuses to tour. Now I get it. You can't blame these bands or their fans for continuing to seek after that old spark, even if it inevitably becomes a springboard into nostalgia for the glory days.