A few days ago, Julien Baker announced a livestreamed record-release show for her third album Little Oblivions, and she tweeted out a disclaimer: "be warned we’re a post rock band now." Baker wasn't using the royal "we," and she wasn't really joking, either. The "we" part is noteworthy since Baker has been holding big rooms in rapturous breath-holding silence for years now, and since she's been doing it almost entirely on her own. Touring behind her staggering 2017 album Turn Out The Lights, Baker was the only person onstage for most of the night, every night. The violinist Camille Faulkner would accompany her for a few songs, but otherwise, Baker did everything herself. Baker played piano, she played guitar, she built rise-and-fall cathedrals of catharsis out of those two instruments and some loop pedals, and she sang with all the raw immediacy of a torn-off scab. To be in those rooms was to feel an overwhelming sense of intimacy -- this one person with the guitar and piano and effects pedals singing about her fears and needs, tearing your soul to shreds. But now she's a post-rock band.

https://twitter.com/julienrbaker/status/1362815859836739586

"Post-rock" is a difficult thing to properly define, but the music that the term calls to mind -- Explosions In The Sky-style slow-release instrumental tingle-vroom, mostly -- has nothing to do with what Julien Baker has done in the past. Post-rock bands rely on emotional release, just like Julien Baker, but they build that release out of textures and dynamics, not out of words and voices, which are usually absent. I tend to think of post-rock as headphones music -- music for walking around and feeling like I'm in a movie. There's a sort of numb removal to this music; it lets you float outside yourself, thinking of your own body as a figure in a landscape. Baker's music -- indie rock tinged with folk and emo, spacious and intimate and almost confrontationally self-lacerating -- offers its own comforts, but they're not the same. Still, listening to Little Oblivions, you can tell what she means with that Twitter disclaimer. Baker's new album is about numb removal, and it speaks the language of swelling, crashing heartache.

Baker arrived on the national stage as a recovering teenage addict. On her first two albums, Baker sang about depression and connection and self-destruction with grace and fervor and soul-searing urgency. She made those albums on her own, producing herself and playing almost all the instruments. Baker recorded Sprained Ankle, her 2015 debut, on a single microphone. The music was grand but spartan, and it left her nowhere to hide.

For Little Oblivions, Baker is again working on her own, but she's doing everything differently. Little Oblivions is a full-band record. Baker has surrounded her voice with layers of sound: Guitars, pianos, bass, synths, drums. It almost doesn't matter that the full band is basically just Julien Baker herself. Baker, who again produced herself, played all five of those instruments on Little Oblivions, even though not all those instruments are native to her. (Baker to Louder Sound: "I am super bad at drums. Like, yeah, I played the drums, but it’s more like I imagined the drums. I hit the instruments. I don’t want people out here thinking I’m better than I am.") Other than her engineer and collaborator Calvin Lauber, who plays some additional instruments, and her boygenius bandmates Phoebe Bridgers and Lucy Dacus, who sing backup on "Favor," Baker is the only musician on Little Oblivions. She still sounds like a whole band.

The sound of Little Oblivions is majestic deep-sigh stuff. Even if you don't listen to her lyrics, this stuff goes after your heartstrings with merciless vigor. Ringing, Edge-style minor-key guitars drone melancholically over soft plaintive pianos. The drums are programmatic crunches, muffled and mechanistic. (Baker is a better drummer than she'll admit.) Soft acoustic guitars halo Baker's voice, which is wracked and bedraggled but somehow still triumphant. This is music built to make you feel something, even if the lyrics are about the seductive urge to feel nothing.

The backstory of Little Oblivions is this: In 2019, after being clean for six or seven years, Baker relapsed. She's back in recovery now. Much of Little Oblivions is consumed with the vivid, searing guilt of being in thrall to addiction and a drain on the people you love. Baker can conjure the futility of fighting for your own soul with a single image: "Day-one chip on your dresser, get loaded at your house." She sings about the power of drugs and alcohol, of finding ways to chemically blot out the rest of the world: "I miss the high, how it dulled the terror and the beauty/ Now I see everything in startling intensity." But she dwells more on the nightmares that follow: "How long do I have until I've spent up everyone's goodwill?"

Baker really goes hard on herself on Little Oblivions. She warns the people in her life that she's just going to do more terrible things to them: "If I didn't have a mean bone in my body, I'd find some other way to cause you pain/ I won't bother telling you I'm sorry for something that I'm gonna do again." She brushes off empathy: "It's too kind of you to say you can help/ But there's no one around who can save me from myself." She accepts full responsibility: "I wish that I drank because of you and not only because of me/ Then I could blame something painful enough not to make me look any more weak."

It's not easy to talk about this stuff, to live out private hell in public, and Baker talks about that, too: "Beat myself until I'm bloody and I'll give you a ringside seat." She also seems to lament the idea that people will keep forgiving her: "Nobody deserves a second chance, but honey, I keep getting them." Her lyrics are specific and unsparing, but they resonate even with those of us who haven't gone through recovery. My own personal baggage is nothing like Baker's, but plenty of what she sings on Little Oblivions still hits deep inner chords for me. Baker was not, for instance, brought up Catholic, but those of us who are viscerally familiar with the concept of Catholic guilt can find plenty of commiseration on Little Oblivions.

I'm worried that I'm making Little Oblivions sound like an unpleasant chore. It's not that. It's not a difficult listen at all. It's beautiful. Parts of the album make me think of Elliott Smith or Tori Amos -- two other poetically honest musicians who started out unrelentingly stark but gradually came to master the art of orchestral grandeur. I can't say that Little Oblivions is better than Julien Baker's last two albums; I don't even really know what that would mean. I can, however, say that the album, for the few weeks that I've been living with it, has been a comfort and a light. And I can say that Julien Baker is now my favorite post-rock band.

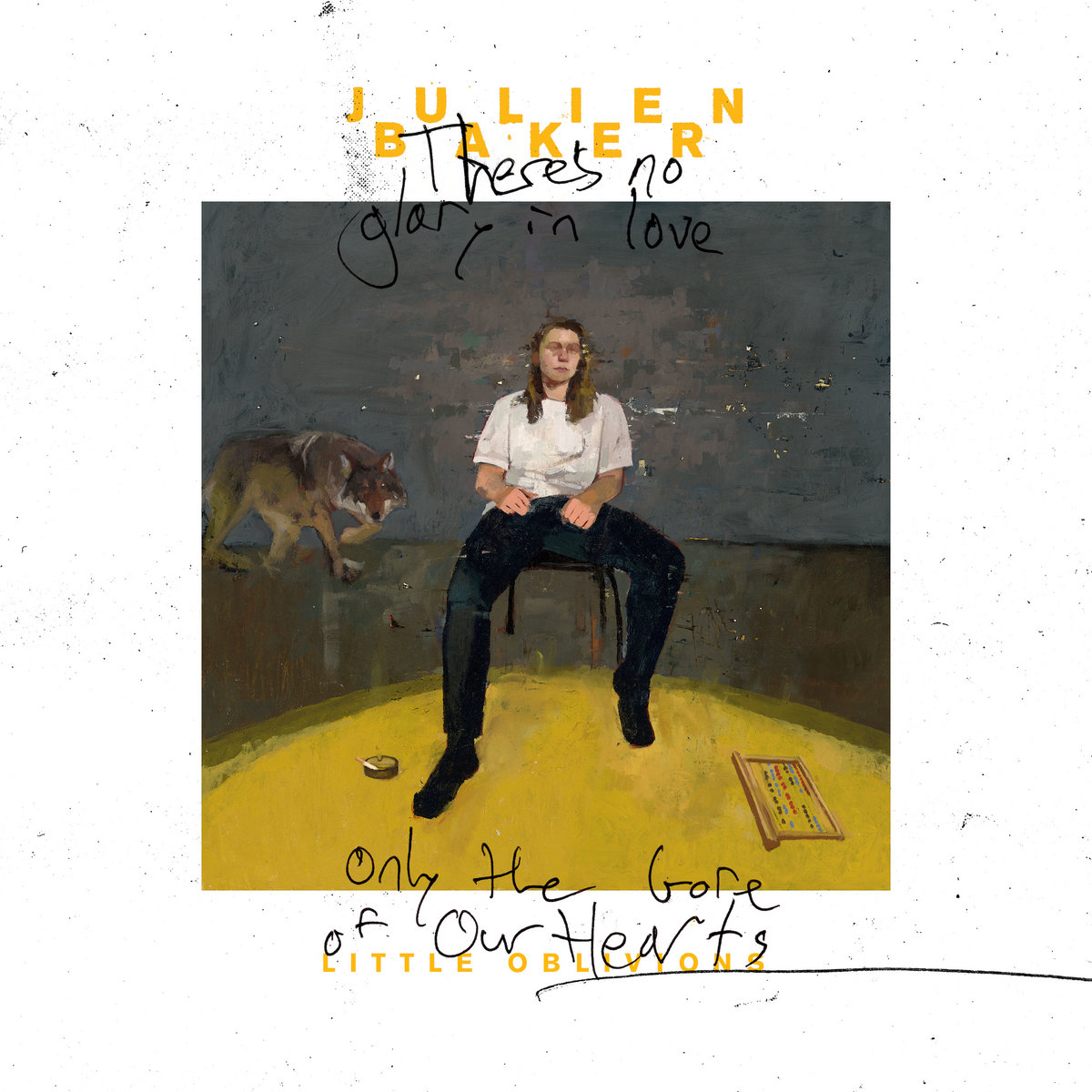

Little Oblivions is out 2/26 on Matador.