Over the past decade, Benjamin John Power has chased increasingly visceral highs as Blanck Mass. While the self-titled 2011 debut album initially suggested a softer ambient side to Power’s main gig at the time -- as one half of the dormant noise duo Fuck Buttons -- his following releases have been built on brutal rhythms, manic melodies, and distorted screams. Gradually perfecting a blend of harsh industrial sound design, euphoric UK rave, and the most hyper-aggressive strains of ‘90s video game music, the albums Dumb Flesh, World Eater, and Animated Violence Mild form a breathtaking and apocalyptic panorama.

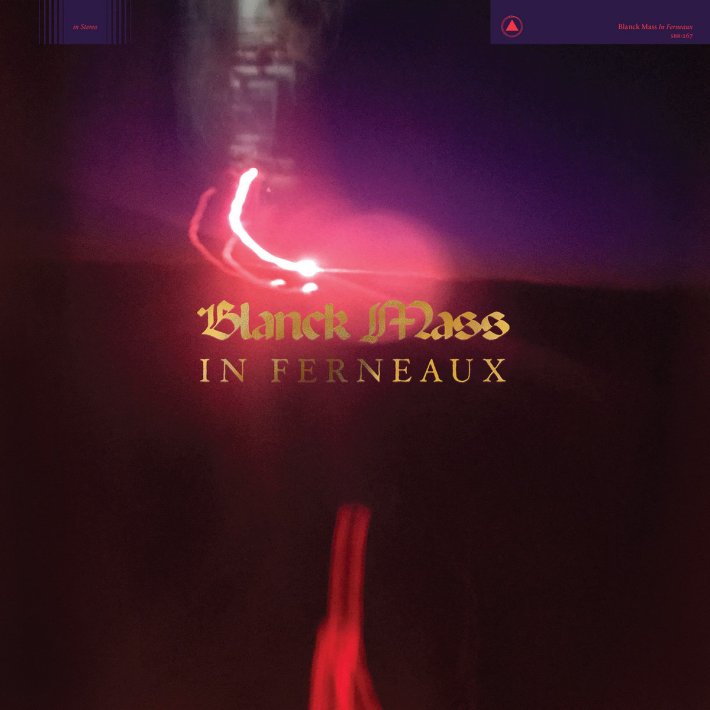

One of the greatest strengths of In Ferneaux -- Blanck Mass’ fifth album, out tomorrow on Sacred Bones -- is how effectively it plays off what came before. The opening single “Starstuff” builds its twinkling arpeggiated synths quickly towards a searing climax, but as the shimmering melody fades to an outro of garbled noise and crackling embers, something very strange happens. The “outro" just keeps going. And going. And as the minutes stretch and the sounds of birds and distant waves fill the ear, In Ferneaux patiently reveals itself as a wondrous experiment unlike anything Power has made before.

The product of a time spent in isolation while grieving the loss of a loved one, In Ferneaux feels like the first post-apocalyptic Blanck Mass album, the loneliness after the chaos of his earlier work. There are no songs or tracks, only wreckage stretched across two 20-minute collages built from over 50 fragments, sketches, and personal field recordings stretching back the last 10 years. Rather than ratcheting tension at every turn, Power does more with space, carving wide atmospheric expanses that feel exposing in all their vastness. Though its dark corners recall the haunted musique concrète of industrial pioneer Nurse With Wound, In Ferneauxalso hides some of the most cathartic passages Power has recorded. It contains tranquil glimpses of nature, orchestrally-minded swells, tender melodies, and uplifting words -- the last delivered from a charismatic street preacher whose appearance recalls the ghostly voices conjured in Godspeed You! Black Emperor’s best work. Without spoiling too much of In Ferneaux’s surprising twists and turns, I called Power up to discuss his brilliant puzzle of an album.

Was there a point as you were collecting all these recordings that you realized “Oh, this is the album.”

BENJAMIN JOHN POWER: It was a strange one, it kind of happened organically to a certain degree. I always carry a Tascam around with me, whether it’d be me on tour or just traveling or whatever. So for the past decade, I've been collecting these countless field recordings and it’s something that really interests me, like an audio snapshot as opposed to just a photograph. You get an extra sense to experience, but you know how sometimes a certain smell will jog your memory or a certain taste will jog your memory and you can't quite pinpoint exactly where it is? I really like to have that extra aspect.

I’ve then gone and used field recordings in a roundabout way, so it’s not a new thing for me with my records. But a lot was going on with me personally over the last years and then obviously when you're put into a lockdown situation you can't be outside and you can’t share memories or make new memories. I started to put together what would become In Ferneaux. It’d been a curation for a year or so, but during the lockdown seemed as good a time as ever, like I was ready to kind of document where my head has been at trying to traverse grief. And I felt a fitting tool would be to use these field recordings that I’ve collected over the last decade to kind of portray how I felt at the time during lockdown.

You talked about how you've used field recordings before in your work and incorporated them into songs. Obviously with In Ferneaux there's nothing they're hiding behind, they’re sort of exposed. Was it a challenge to put yourself in that mindset or was it something you felt naturally drawn to?

POWER: It’s liberating and in the same breath terrifying, being that open and sharing something. Historically, I’ve hidden behind a wall of sound with regards to Blanck Mass and Fuck Buttons, so you do feel kind of naked. For that reason it’s extremely cathartic, but it’s also terrifying. It’s just so personal. I wasn’t sure whether I’d gone a step too far or if it was too earnest in its delivery. So to have people come back and appreciate it is extremely rewarding and I feel very touched by that. It’s not the most accessible or poppy thing I’ve released. So it did feel like I was making an album that was a bit too far flung, but I guess I need to give people more credit.

The album’s opening section was released as the single “Starstuff” and then it was also on a Sacred Bones compilation last year.

POWER: It was and then it got reworked. I felt like that had a real place because it was around the time when I started to really put In Ferneaux together when that compilation came out. It felt like a very apt starting point for the record. To me though, that can be read as like the initial stages of grief or maybe what comes before grief, when there's an uncertainty and you're just thrown into a situation at 100 miles an hour. So I felt that was what I wanted to try and then you're dropped into the unknown, you're dropped into uncertainty. There's uncertainty and then you’re just headfirst into a situation which is never going to change and you don't know what to expect.

Yeah it really stuck with me how it fades out and you kind of have that expectation like “oh, the next song is going to start” and then it just hangs in the space and it just keeps hanging. It doesn’t give you that release.

POWER: You’re thrown into the world, then.

In terms of chronology, what was the earliest recording on here? What was the most recent?

POWER: That’s interesting. I couldn't say for sure which is the earliest, but there is some stuff on there that dates back seven years, maybe longer. The second part of “Phase I” is actually a combination of two elements. You've got fire, there’s a fire from the Isle Of Orkney in it. And then there's also water from some docks. So you're thrown into this new landscape. I really wanted these two very elemental forces to be very prominent at this point because that is all you're kind of left with after you've been through this tunnel at 100 miles an hour. They sit really well together -- it sounds like it could be the same field recording -- but they're actually recorded about seven, eight years apart from each other.

The most recent one -- I feel like there's some stuff from New Zealand in there, which I actually added extra percussive elements to, about half of the way into “Phase II.” Then there's some forest sounds, they're from New Zealand as well. So that would have been last January, just before the lockdown. My brother lives in New Zealand you see, and I visited him end of January just before lockdown happened. It was probably lucky that we didn't have our trip booked for March or whatever because I wouldn’t have been able to get home. I hadn't actually considered that, but that would that would be the case. So thank you for that. [Laughs]

Did your approach to recording change when the focus shifted from playing music to now handling this archive of old sources and working in a collage sense?

POWER: Apart from some of the field recordings on there that are pretty raw and left untouched, I’m still putting them through pedals and things like that in the same way I would write music on synthesizers. And it’s always been very exploratory and kind of naive in the very first instance, just trying things out and see what works and building. So it is kind of the same way I’ve always worked, I’ve just been using very different tools. And as you can tell there are a lot of synth movements sprinkled in around the field recordings and on top of the field recordings as well. So the process is still the same, but the approach is a little different.

On previous albums, we got to hear your vocals again. This one doesn't have you singing, but the beginning of “Phase II” captures this really memorable recording of a preacher that becomes the one main vocal presence on the album. What’s the story behind that recording?

POWER: That was actually a chance encounter that I had with somebody whilst I was in San Francisco, and it actually kind of paved the way for this record becoming what it actually became. I was struggling with a lot of stuff at the time when I first made this recording, and the conversation I'm having is with this person who as you can hear has faith, which I do not myself have. But the message is still the same, however you interpret it. This person suggested to me that I don't have the tools at the moment to handle the misery on the way to the blessing. And in this instance, it gave me a kick and a jumpstart into actually using these field recordings -- one of which they are part of now, too -- to actually try and use it as a tool to overcome what I was going through.

And, you know, the blessing in that sense is In Ferneaux and being able to share it with everybody. So that was very pivotal for me, and a moment of clarity and realization. And I feel like for that reason, it's maybe one of the most powerful field recordings on In Ferneaux and it has a home there and is relevant within the context. Without that conversation, I'm not too sure we'd be speaking about this today.

Were there any older albums or artists that you looked to when going into this more collage structure?

POWER: With regards to albums, I’d say that there’ve been comparisons made I had not considered but of which I’m a fan, and to hear somebody talk about In Ferneaux in the same breath, it feels great to me. One thing that’s come up a couple times is that Godspeed You! Black Emperor album Lift Your Skinny Fists, which I hadn’t considered. I haven’t listened to it for a good few years, but that’s definitely something that I used to listen to a lot and find inspiring. Artist-wise, I’m a big Cabaret Voltaire fan and Chris Watson, he’s the field recording master. So that was certainly something that has been inspirational to me throughout the years. I love how he manages to capture some of the more unforgiving elements of the natural world. It's very raw. And I've always found that pretty fascinating.

But regarding the actual process -- I'm so wrapped up in my own little world when I'm making a record that I often often find myself behind culturally. I just keep long hours in the studio and I'm quite bad at keeping up, but those are definitely a couple of historical references. Obviously, the idea of narrative is something that really plays into everything I do. I started to work more with scoring movies and that's something I've wanted to do since I was very small. So I feel like narrative has always been a very prominent part of everything I do creatively and artists like Ennio Morricone have always been a huge influence on me with regards to not only space, but composition and the idea of a narrative-based audio experience.

Where have you been during the pandemic?

POWER: I live in East Logan, in Scotland about 14 miles outside of Edinburgh City Center. So it’s actually reasonably easy to self-isolate and try to stay away from public spaces that might be a risk. I’m also in the countryside, so it’s reasonably easy to stay safe.

And you made the whole album from that space?

POWER: Yeah, I spent hours and hours and hours in here, in the room I'm speaking to you from right now. This is where it was all made. It's very strange using field recordings in one particular room. It's bittersweet, especially kind of processing that time, some of which were during the grief process, some of which were from years before. It is quite a bit of an emotional rollercoaster when you're confined within four walls. It’s very bittersweet.

Yeah. I know the feeling very well. Just when you don’t have much in terms of distraction blocking you from grief. You’re stuck with it more.

POWER: Yeah, it’s somewhat diluted if you can be around other people. I don’t know, because I’m not in that position. I’m still not in that kind of position, so it feels like everything is intensified. So that’s why this record to me feels like it has the most emotional weight. It’s strange not being able to see family members and such that you would normally be spending time to process these kinds of things.

Did the experience of making this make you think differently about how you would make music in the future?

POWER: The process was so intense, I don’t know. Maybe the next time I make another record, I would want to make something looking towards a future in a physical space. This record, it’s about a very particular time for me using historical artifacts, it’s a particular screenshot. But as far as process goes, it has been liberating, so I’m sure there’s tools I might utilize in the future. As far as the construction of a record goes, these are two long tracks that have lots of movement within. I feel like that’s something that interests me anyway, so to be able to have done this now because of these reasons, it’s definitely something I’ve found to be of benefit.

This might be totally abstract right now, but did you have any thought about how you might perform something like In Ferneaux live? Unlike your other albums, it seems so difficult to imagine it in a physical space.

POWER: I think it's way more internal, more heady. But I have been asked about this before and I feel like it would be interesting -- and I'm not saying for a second that this is something I'm planning on doing because I can't see where the future lies -- but I do like the idea of working with an orchestra or a stripped-down orchestra or something like that for these tracks. I feel like they lend themselves to it. I've always wanted to write music for an orchestra. The very first Blanck Mass record, I was broke and I was living in a really small flat in London and these were tracks that I'd written with my synthesizers that, in my head, were orchestral pieces. But I didn't have the means or financial anything to go ahead and make that happen. So I had to make the best out of what I had to get that message across. I would still really like to do that and I feel like the music on In Ferneaux would probably lend itself very well to that.

Do you know how many field recordings went into the record in the end?

POWER: A lot of stuff would get put in place and then replaced, so in its entirety I’d say 50 or 60 field recordings made the final cut. But I have hundreds and hundreds of these. Going through them all to try and figure out the process of selection was sometimes quite ruthless. There were things I really wanted to put in the record that maybe had a particular resonance with me, but weren’t working texture-wise. There was some stuff from Costa Rica where I was getting chased down the road by a howler monkey that I really wanted to try and find a place for, but it didn’t make the final cut.

That editing process must be new in some way. There must be so much removing.

POWER: Yeah, there’s a lot of subtraction here. And it was a bit more than I'm used to because usually I build up. For example, the stuff on Animated Violence Mild, I'm filling up the space until it's so claustrophobic that there's no more space and then taking things out and kind of chiseling away. But obviously with this stuff, you have to be a lot more ruthless because even though I'm subtracting a lot of stuff on Animated Violence Mild, you still are presented with something that resembles a wall of noise a lot of the time. The space is way more wide on In Ferneaux, so it’s a lot more ruthless.

In Ferneaux is out 2/26 via Sacred Bones. Pre-order it here.