Little Oblivions is the bleakest, brightest Julien Baker album yet. It's not quite accurate to say that Baker's third LP, out today, pulls the time-honored trick of matching sad lyrics with upbeat, poppy music. She continues to set her thoughtful confessionals to chords and melodies that emphasize the heart-wrenching beauty of her words, bringing the high drama of emo and post-rock to bear on singer-songwriter indie rock. But even as the Nashville-based artist ventures into some of her darkest lyrical territory yet, her arrangements explode with unprecedented life and color.

If 2017's Turn Out The Lights saw Baker stepping the ghostly ballads of her 2015 debut Sprained Ankle into hi-fi splendor, this one significantly expands her sonic universe. It's her first full-band record of sorts, even if that band is mostly just Julien Baker. Recording in her Memphis hometown with her longtime engineer Calvin Lauber, Baker traded out her signature minimalism for something grander and more visceral. Essentially producing and performing the whole thing herself, she incorporated a wide range of sounds, from electronic beats to alt-country pocket symphonies. Her songs still swell into moments of intense emotional and spiritual reckoning, they just hit harder and cast a wider net.

Still, to listen closely to Little Oblivions is to stare into the abyss. Baker, 25, struggled with addiction as a teenager, an experience that has informed much of her songwriting to date. In 2019, she decided to try drinking again, thinking she might have more of a handle on herself after a few years of growing up. Instead, the resulting downward spiral reopened old wounds and accelerated the process of reevaluating everything Baker thought she knew about herself. She wrestled with deep guilt over her failures as a person and found herself largely alienated from the Christian faith that had always been a foundational element of her life and music.

As these struggles shaped her first collection of solo material in almost four years, Baker allowed herself to write from a place of complete honesty. For the first time, she did not attempt to steer her songs toward some kind of hopeful resolution. The result is an extremely heavy listen, a mournful and often angry album that saves its harshest critiques for Baker herself. Allusions to violence, substance abuse, and even suicidal ideation abound. This is a portrait of a person in crisis, one that offers no easy answers but surrounds its rawest declarations with pristine beauty.

On a January morning just days after the Capitol riot, I connected with Baker over Zoom to discuss the backstory on every song from Little Oblivions. Some of the anecdotes and reflections went deeper than others. Some pivoted into fascinating tangents. Given Baker's status as one of the most thoughtful interview subjects in music today, the discussion never ceased to be compelling. Press play on Little Oblivions and read our conversation below.

1. "Hardline"

https://youtube.com/watch?v=6pGBIAiJPF4

I love the way this starts out. It just immediately sounds bigger and louder. And the intro actually reminds me a little bit of "Sicko Mode," the Travis Scott and Drake song.

JULIEN BAKER: Thank you. Wow, I would not have drawn that comparison. But the fact that you did is incredibly flattering because I love that album Astroworld as a complete body of work. That's a great song. I want people to hear the song "Hardline" and think, "That person listened to Manchester Orchestra in high school. That person wants to have huge epic driving major chord guitars."

Was it a conscious decision to open up with that song? Like, "We're going to make like this grand opening gesture here?"

BAKER: Yeah. I tend to have difficulty thinking of tracklisting in a way that's separate from setlist making. So I think originally the first track was "Bloodshot." But then we were playing around with skipping things around, and it felt good to put the most abrasive song -- or at least in my opinion, maybe like the heavier song -- right up front, as an introduction to, "This is the extreme of what the record will be." And then from here, you're establishing a limit to the spectrum of where the record will fall.

The opening lyrics are "Blacked out on a weekday, is there something that I'm trying to avoid?" Do these kinds of lyrics refer to real-life anecdotes? Are they from a long time ago? Are they recent?

BAKER: Basically all these experiences are things that have happened to me in 2019. I felt a certain amount of apprehension, disclosing all of those things in a record or even validating or legitimizing them, or taking away some mystery by confirming or denying stuff in an interview. Because I don't want it to seem like -- I don't want to utilize these extremely bleak periods of my life as some sort of accessory to how I'm perceived. I don't want to sensationalize these things. These are experiences that I've written about before because they're similar to experiences that I had in childhood and teenage-dom. And then I became sober. And then revisiting the experience of substance abuse, and finding new dimensions of bleakness that I think, had become a little bit duller in my memory, and had started to turn into an easy narrative of, "These are the dark things that happened to me in the past. Now, I'm still dealing with the emotional fallout and the emotional scars of those things, but there's a clear separation between former me and current me."

And with this record, it was very humbling to -- I mean, the "Hardline" title is a not so subtle breaking edge reference, which was cheeky and dark humor on my part. But also was a reference to something that was actually very disappointing to me about myself and about the way that I had constructed my identity, and finding out the new me and old me are not distinctly separate entities. I still am a person who experiences difficulty with substance abuse, and I still am going through these crests and troughs of recovery. It's nonlinear. So yeah, I don't know. I want to be candid about it, but I just don't want it to seem like, "Listen to all this horrible stuff that happened to me." It's more just admitting that I think I had been naively idealistic about myself, and trying to come from a place of honesty in divulging all those things.

2. "Heatwave"

https://youtube.com/watch?v=ZaEAbleWSjs

This stood out to me as one of the darkest songs on the album, especially with the ending line, "Wrap Orion's belt around my neck and kick the chair out."

BAKER: I forget that's a lyric in there. I almost didn't put that in there. I was like, "That is very cringe-ly dark."

It certainly lives up to that idea of being candid and raw about your experience. How is that helpful for you? And how do you hope that it will be helpful for listeners?

BAKER: Oh, man. It's interesting. I think especially with this record, it was written over the course of a longer period of time, where I had a lot more room to tinker and consider production, but also the lyrics of songs and how to phrase things. But I was alone for most of it. I wasn't on tour being constantly confronted with the reminder that comes from a live show, that people are hearing this and these ideas are bouncing off of other people's brains, which I think on Turn Out The Lights made me want to -- it made me feel a deep responsibility to craft lyrics about the dark things I was experiencing in my life in a poetic and meaningful way, that ultimately had some thesis of brilliance redemption, or healing.

And with these songs, I was just at home trying to process things that were happening to me, in my real life, without so much of the looming awareness of the art later being observed. So there are several songs on the record where my impulse was to change them. And that's one, especially the last chorus part. I was like, "Is this OK to say?" And then I felt that way about many of the tracks on the record. And whenever I feel that, I don't know, maybe it was just like me being a contrarian or me feeling like I always have to perform honesty in the best way that I know how. But I was like, "OK. Well, if I'm scared to disclose something, why? And what is that telling me about my shame or fear?" And ultimately, the things I'm most scared to disclose maybe are useful to bring into a discourse through music, but also, maybe they're not. I have a real fear that maybe they're just triggering, and a tool for wallowing. Of course, that depends on how the listener uses them. But I'll never know. And I think letting go of not knowing has been helpful for me, just as a writer, being able to not feel so stilted.

You were describing the need for a redemptive element on Turn Out The Lights, versus just processing in the most authentic way possible here, even if it didn't feel redemptive at the time. I hear this record, and it's like, wow, it's powerful -- it's a powerful example of human experience and how it's not always the storybook ending. There's a lot of pain in the moment being depicted there. To be able to capture that and put that out there, without resolution. aside from the concerns about how people are listening to it, or how they're going to use it -- as just a pure creative endeavor, it's really powerful and magnetic.

BAKER: Thank you. I don't know, this probably has some weird convoluted effect on my psyche, but when I was a kid in middle school, and I would read rock bio books because we were constantly encouraged to read, which is a good thing. But then I didn't want to read, like, Little House On The Prairie. So I would read -- I read all of Scar Tissue by Anthony Kiedis, all of it. It's like so many hundreds of pages long. And so there are some insightful works like that. And then there are some works that are almost like this catalog of the most sensationally messed up substance experiences, or sexual experiences, or show experiences. It's just like, a catalogue of chaos organized into something that is ultimately appealing to people because it is sensational. And it's so far from the life that maybe a person who picks it up at Barnes & Noble would live. So that was my fear in saying all this stuff. But ultimately, I think there's a little bit more artistic liberty in songwriting, where you get to be really visceral about the emotions behind those experiences without leaving them to just be a shock value.

So to pivot into something a little bit lighter: This song almost has a roots rock feel, like you're tapping into your Southern heritage a little bit. Was that intentional?

BAKER: It didn't come out so -- and this is true of every song -- I'll have an idea when I first write a song and its chord progressions. I'm like, "Oh, I want it to sound like this vibe." And I originally wanted it to sound way more lo-fi and like Songs: Ohia, lo-fi guitar, and it came out to be a little bit more bouncy, like you said, roots rock, kind of. It has like a country swing to it.

Instead of Songs: Ohia it's like Magnolia Electric Company.

BAKER: Yeah! There you go. And I think over the last couple years I've been doing like a deep dive on Isbell and Drive By Truckers and Lucero, like the Memphis folks. And then, like, Uncle Tupelo. And I love that kind of music. So I just wanted to allow myself to write the music that came naturally to me, even though it seems like an oddball of the record in its genre leaning. Or, like, genre is a myth.

3. "Faith Healer"

https://youtube.com/watch?v=bWAOkg2i6_g

Why was this chosen as lead single?

BAKER: Originally, it wasn't. I turned in the record and I wanted "Ringside" to be the single, I think. And everybody really dug "Faith Healer." And this has happened to me before. It happened to me with "Turn Out The Lights." I was just like, "Really? That song?" That happens to me every time I have somebody talk to me about my music. I'm like, "Really? That song? That's the one you want?" Which I only say because "Faith Healer" was like a particularly difficult song for me to get to a comfortable place with. I tried that song in different time signatures, and different arrangements. And I had been sitting on those lyrics for years.

And it was one that was particularly arduous to make, that I felt like was maybe most experimental or risky? But I don't know, when I turned it in, the people at my label and on my team and everything were just like, "We really like this song." And I was like, "OK. Well, I guess my level of expertise is" -- I try to have an open hand with stuff. I'm like, "I guess my level of expertise is maybe making songs and thinking about music and you guys maybe know better than me, I don't know." But also, I find in the nature of releasing music, especially now, singles maybe matter less, depending on what genre you're in. Even though we have an immediacy of streaming services allowing you to hop around to infinite artists at once, I do find that people want to engage with the record as a body of work. So yeah. I was just like, "I suppose this is as good of a representation of the record as any song might be."

4. "Relative Fiction"

This has got that line, "If I didn't have a mean bone in my body, I'd find some other way to cause you pain." Is that a Built To Spill reference?

BAKER: Oh, gosh! You know what? It probably is a subconscious one. I didn't think about that until the moment you said it. And now it's just like, "Damn." That happens with so many songs on the record. I was joking with Calvin that I'm just going to put what band I ripped off in the lyrics as the title of all the songs. Like "Heatwave," the "wrap Orion's belt around my neck and kick the chair out" line is a reference to a Format song off of Interventions And Lullabies called "Tie The Rope," which is also like a really upbeat rock song about self-asphyxiation, which is dark.

But yeah, anyway, I just wrote that lyric because: Everybody wants to believe this about themselves maybe, but I legitimately want to try to not hurt anybody's feelings, or make anyone mad. That's just a deep fear, maybe, of everyone. And then it's like over this course of time, where I'm making mistakes that seem like a self-imposed circumstance, but that I don't deliberately want to hurt anybody. I think that line is just about ruminating on the inevitability of hurting people, and trying to make peace with that. About how even with best intentions, human beings are going to hurt each other, and be selfish and make mistakes that are inadvertently hurtful. And that is sad. But it's also something you can come to have a little bit of patience with yourself about. I don't know.

You later on say, "I've got no business praying, I'm finished being good. Now I can finally be OK. And not the way I thought I should." I'm wondering if you can elaborate on the attitude that's been reflected there.

BAKER: That is like a direct rip from this thing one of my friends said to me when I was in a super dark place. And they were like, "Do you know that John Steinbeck quote that's, 'Now that you're not perfect, you can just be good?'" And it made me want to cry. I'm a person who loves cheesy literature quotes, but that one especially it was like, "Wow." When we eliminate the ideal of perfection for ourselves, we maybe come back to a place where we can reasonably achieve a modicum of goodness without penalizing ourselves for failing to be perfect. And I don't know, that song is admittedly pretty pessimistic. Just because I think, especially on Turn Out the Lights, I felt a need to craft songs in a way that weren't angry and were somehow helpful or redemptive.

And that this one I just was -- I think maybe disillusionment is not the correct word. I don't think it is because there's a lot of malice involved in the connotation of disillusionment. But I felt like, basically, I had tried to live my life as an extension of my faith, however non-traditional my practices of having a relationship with God were. But I wasn't for all of this fixation on what God wanted me to do. I wasn't able anymore to use that to make myself a better person. In fact, all I was able to use my ideals for were, showing me how I did not live up to any of them perfectly. So I think I angrily was just like, "I'm OK. I'm finished trying to be good. I can't be good. I am a bad person." Which of course, I don't believe, but yeah, I'm an unhealed person still. And I fail at a lot of things. I don't maybe necessarily feel that fatalistic about it now, but I certainly did when I wrote it.

I guess as I understand the New Testament, isn't that the whole thing? You admit you aren't good, you come to the end of trying to be good, and you try to accept some mercy? Not that there's no attempt to have some positive moral impact on the world, but you quite literally give up on the idea of living up to perfection.

BAKER: Sure. Yes. Ideally, that's how everyone would understand it. I'm thinking of the Marilyn Robinson book Gilead, where it's like from the perspective of this pastor and he is basically writing in his journal. Like, "I don't understand why people come to me every week." You get told once like, "You're saved. You're forgiven." And whether that's like a cultural thing or a mythological storytelling or a literal thing for you. Ostensibly, you get told, "Yeah, you're saved once and for all." And then you just go about your life trying to show the same mercy to other people. That's not actually how it works, or how people are socialized to understand religion, especially in Evangelical, western United States Christianity.

I was going to go on a big theological thing and like, quote, a bunch of scripture, because I have so much scripture committed to memory that I'm just like, "What do I do with this now?" Especially when I'm trying to explain stuff to people who maybe don't have such an intense faith background. And then I'm just like, rattling off Bible verses, and they're like, "Whoa!" But yeah, it's like you would think that's how it works. But then because we're human beings, there's still this weird longing for continuing to seek validation about it, and then turn it into this meritocracy/

That's why when people collapse their political ideologies, and, like, vote their conscience. It makes me feel like it makes -- especially the things that have happened over the last couple of days, have made me feel so disconnected from religion as an institution more than I ever have. Because I realized how really all the tenets of Christianity in a Western context are just pushed around to justify whatever moral social behavior people want to use it for.

5. "Crying Wolf"

This has another reference to tying knots. Is that alluding to a noose again? Or maybe I'm misunderstanding it.

BAKER: Well, it was going to be a rhyme that I left off the song because I feel the need to make everything rhyme. And I wanted to override that impulse. But it's more of a dual reference. There's the most immediate, dark way to take the tying of a knot, but also, the next lyric was going be: "So I tied a knot and cut you loose." And it was going to be about forming relationships with people, like tying a knot. Like getting married, but also just being in long-term relationships. Or maybe understanding that this person who've tied yourself to, you now have to distance yourself or renegotiate that relationship. Or maybe just completely sever ties with that person, depending on how amicable it is. So it can be construed as completely dark, but it doesn't have to be.

6. "Bloodshot"

I love the drums on this song. This is one of the more electronic sounding songs on the album.

BAKER: The drums on that song, it's like live drums mixed with triggered drums. Not triggered but drum machine drums. And then it does have live bass on it. But it has that crazy, like, JUNO synth in it. Yeah. I like that song too. That song is, again, bouncy and upbeat in a way that I didn't expect to have it turn out, when I was initially writing it, as like a moody 10BPM slower song.

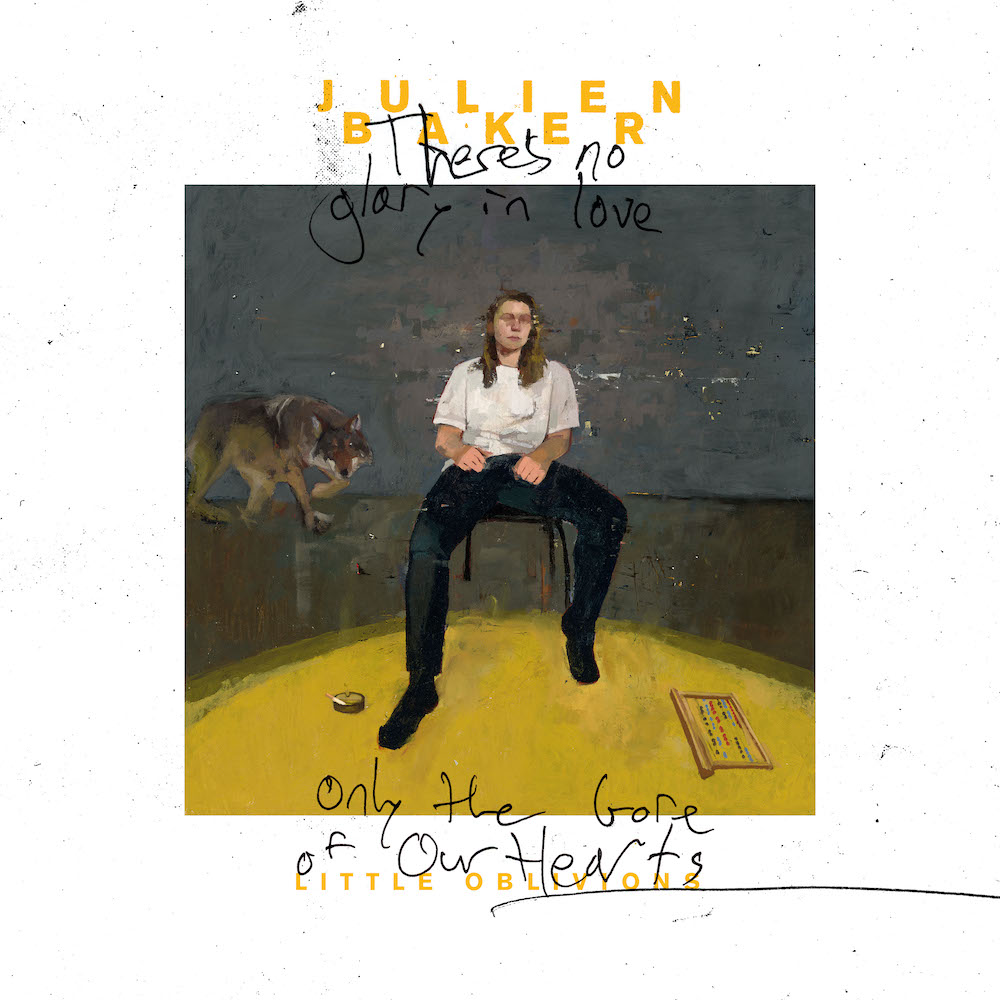

You mentioned about working hard on the lyrics and really trying to craft these memorable lines. One that really stood out to me was the, "Oh, there is no glory in love, only the gore of our hearts." I especially loved the way that you sang the melody on that song. There was just something really attention grabbing about it -- it felt almost like a different melody than what you normally sing.

BAKER: Yeah, the melody is really weird. There are so many songs where I was like, "Is this melody uncomfortable because it is outside of the intuitive arrangements that I usually do?" And that I was like, "I think this might not be bad, maybe it's just different." It's not that weird of a chord arrangement, but it's just got some chords that I don't usually incorporate in there, like a three minor, instead of going to like a six minor. That weird modal shift is something I really wanted because I wanted to have more experimental chord arrangements. I realized that in my previous records, in my quest to be minimalist and to really strip everything back, I intentionally resisted making anything too modal or uncomfortable. And with this record, I don't know... It was fun to just throw some weird chords in there.

7. "Ringside"

This is the one you said you originally wanted to be the lead single. Why is that? What jumped out from this one?

BAKER: The original demo had this over-compressed Casio-like drum machine noise that I absolutely loved. And the pacing of this song, it felt good to play. I could try to articulate that in a number of, like, music theory vocabulary words, but the song just felt good to play. It's funny because you made that reference to roots rock, but now when we play that song full band and less with the drum machine and more of a live drum sound, it sounds incredibly like a bar band. Like, just an old country bar band. That's the stuff that I have fun playing. It's just like a straight beat. It's simple. And also, that's another set of lyrics that I had held on to for quite a while trying to find a home for it.

I really love: "I'm holding on just like a scratch-off ticket, how I dig my nails into your skin/ Honey, I'm not stupid. I know, no one wins this kind of thing."

BAKER: That's a pretty literal metaphor that I had in my brain since college about the way people come to be in romantic relationships and about how, no matter how much time we spend with someone, we can ultimately know very little about their inner world. And so at a certain point, it is like roulette with the people in your immediate sphere. Or like the people in your city or the people at your work or the people on your social media. You end up just finding yourself colliding or intersecting orbits with a person for a certain amount of time and then having to have the same amount of uncertainty as a scratch-off ticket, as to whether this is going to be a healthy and fulfilling relationship or not.

And it's like, sometimes people win, like 20 bucks. And say you're like, "All right. Well, I won 20 bucks. Maybe didn't hit the $7.5 million Powerball, but..." I feel like when people buy scratch-off tickets, you come into it knowing with this pessimistic idea that the most likely outcome is that you get nothing. And then the most ideal outcome is that you get something that's like bearable or moderate. And maybe you get $30,000 off the scratcher, but probably not, if you have my luck.

8. "Favor"

https://youtube.com/watch?v=UtZxNJEOVnw

Why is this the one that you invited Phoebe and Lucy to sing on?

BAKER: Because this is a song about my friends. The anecdote from the song is not about losing Phoebe, it's about another one of my friends. But they were both in town at some point in 2019. That's when Lucy and I sang on Phoebe's track from Punisher, and Lucy was having some people do a big group vocal on a song of hers. So I thought I would just throw this one into the sharing pile. We tracked them here in Nashville, and we all just sang on each other's songs. And I had just recently made this one, so it seemed appropriate to have them on there.

9. "Song In E"

The way you use piano on this album, it feels like you've found different voicings and rhythms and ways to open up that instrument to write new songs for you. This seems like one of those to me. Do you think that's a fair assessment?

BAKER: Sure, yeah. It's funny because originally this song had almost a country feeling song or -- like, there was a natural C in there that made it jazzy. So I just reached over to my keyboard. I tried to play it on guitar and have it be a lot more chicken pickin' Telecaster, but when we went into the studio to make this song, I was recording with one of my friends, Collin Pastore and he just muted the guitar and went to just the piano, and I liked it so much better that way. It seemed just so much more open.

A line that stood out for me on this one is: "I wish that I drank because of you and not only because of me." I felt like an interesting twist on "it's not you, it's me."

BAKER: I think when you're a person who has substance abuse in your family and a history with addiction, it seems like it would be easier to blame self-destructive behavior on a circumstance. Like, I lost my job, or I'm sad because I went through a breakup, or I lost someone in my life. Ultimately, for me, those things might be catalysts, but I gravitate towards substance abuse because it is a negative coping behavior that I just have in my life and have to deal with and try to find healthier coping behaviors. It would be so much easier if I could blame it on cruelty or heartbreak or disappointment. But when you get to the bottom of it, it's more just a personal insecurity or an anxiety that's deep in my person, not because of external factors. Which is sad, because then you have to work on it inside instead of being able to blame it on a passing situation.

10. "Repeat"

"Repeat" seems like it continues into some of those themes. Like, "When the drugs wear off, will the love kick in?" It feels like there's some thematic repetition, like from song to song you're continually finding new angles to approach it from and new layers of what's going on internally.

BAKER: I wouldn't have even consciously thought of it that way, as deliberately trying to come at it from several different angles. But I wonder if that is just me trying to solve the 100-sided Rubik's Cube of my brain being like, "But what about this aspect of the thing that is wrong?" Which, yeah, I don't know. It's a little obsessive. This song is special to me. The four on the floor kick -- I wasn't sure about it at first. And now I love it. It's like 1% club. And I'm OK with it. I like how that song turned out.

11. "Highlight Reel"

BAKER: This is another one that I had been tinkering with. I had some of the pieces of imagery that I would try to incorporate into other songs for two or three years that finally made this song. It's about being a touring musician. "Repeat" is also about touring, but it's about performance, and reliving all of your worst memories every day. This one is more about this sense of separation I'd feel when doing something in some far-flung place and things would go wrong or things would happen to my friends or in my community that I'm not there for.

That's the first verse, about being stuck inside a car and having a panic attack because you're trapped, and I just want to, like, walk all the way back home to Tennessee and check on my people. The chorus part is specifically referencing becoming disillusioned with people who I had looked at as symbols of good citizens and activists and people in my church and from long ago and having hurtful things happen between us. And wondering, like, I'm going to find out how much of this was real and fake when I die, or when I get to heaven or the next dimension or whatever.

It's really unsettling to think that, for now, my only option on Earth is to sit with that discomfort and uncertainty and then decide how much of this is a farce. How much of this is propaganda? How much of this is me actually trying to be better person and serve God? I think so much more about the humanity of God now and less about the like a Monty Python bearded guy in the sky. But it's a hard thing to be saddled with that. To know, like, "OK, all the people who gave me the information about the things that I believe, all the people that instilled my beliefs in me are fallible and sometimes do things that are even evil." And how do I decide how much of that was a lie? And how much of that do I continue incorporating into my personal beliefs about the world?

12. "Zip Tie"

Why is this the closing song?

BAKER: It seemed like a tender way to close the record, but also one that was consistent with the rest of the songs. It's bleak without feeling like it had to justify itself with some redemption or some provision for positivity. This song is just about me watching the news two or three years ago and thinking, "Do I really think humanity is doomed?" And this is completely within the storytelling and mythology of religion. Sometimes I just see atrocities and think, "Does Jesus ever regret saving humanity?" Because look at what we're doing to each other. And I just feel deep sadness about it. And I know that's really dark. That's not how I feel all the time. But that's definitely a thought that crosses my head. Every once in a while, I'm like, i"Is humanity that sacred if it can't respect the sacredness of other human lives?" Sorry, that's a real bummer of a way to end an interview, but I guess it's a real bummer way to end a record too.

Little Oblivions is out now on Matador. Read our review of the album here.