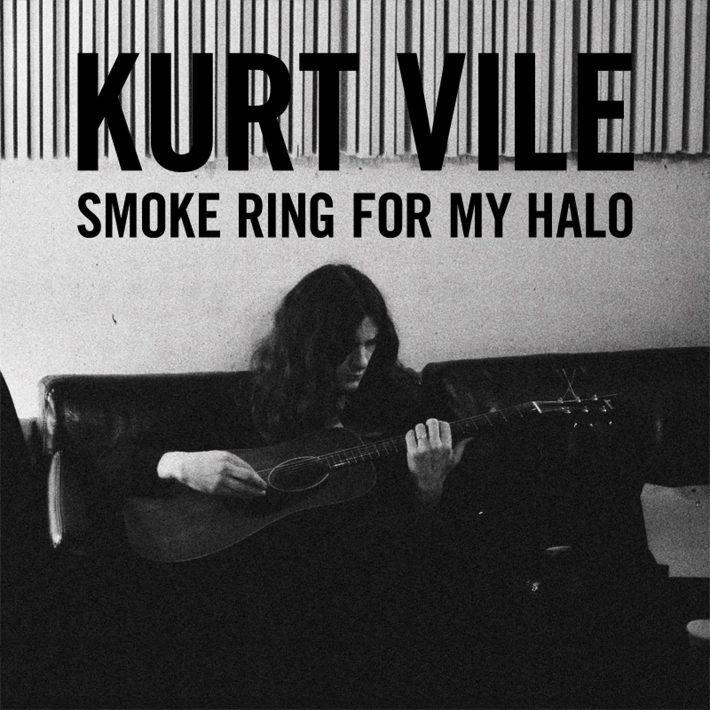

"It's just me and those thoughts you have late at night when nobody is around," Kurt Vile once explained. "It is more a feeling than a statement -- a general wandering feeling. It’s kind of a wandering record."

The man had a good handle on his own work. Smoke Ring For My Halo, released 10 years ago today, is a wandering record for sure. Vile's pivotal fourth LP is less a collection of songs than an assortment of nocturnal vibes, foggy states of mind that play like glimpses of infinity. Even when it rocks, it does so with the faint glimmer of a mirage, as if you might be hallucinating the whole thing. Its ballads are zonked and restless, the sound of a songwriter burrowing deep into his own thought life and discovering vast universes inside. A disoriented glaze covers over everything, even as moments of clarity break through -- plainspoken epiphanies gone slightly askew.

Kurt Vile was born to be a rock star. For one thing, Kurt Samuel Vile is his real name, not some persona he cooked up. Charles and Donna Vile and their 10 children probably could have been punk-rock Partridges if they'd wanted to. Picture it: The Vile Family! Beyond his fortuitous surname, just look at those eyes, that hair, those cheekbones! Not that these career paths are mutually exclusive, but had he not been busy with music, our man could have been a model -- perhaps an actor, too, though his introverted disposition might have undermined that pursuit.

Vile grew up in the suburbs of Philadelphia. By his teenage years he was making primitive home recordings and dreaming of someday signing to Drag City, the mythic Chicago record company occupying a space between "mainstream" indie and the real-deal underground. He'd have to wait another decade or so to become affiliated with a legendary label. Vile spent most of his twenties toiling away at low-wage jobs, famously driving a forklift at one point. After moving to Boston for a spell, he returned to Philly and struck up a close friendship with Adam Granduciel. In 2005 they formed the War On Drugs as a vehicle for Granduciel's songwriting, and Granduciel likewise became a member of Vile's backing band, the Violators. Together they carved out a hazy modern permutation of rootsy classic rock, one that would make stars out of both of them.

By 2008, when the War On Drugs released their debut album on Secretly Canadian, Vile left the band to focus on his solo career. This made sense because Vile was quickly becoming somewhat of an underground darling. His own first album, Constant Hitmaker, emerged that same year to praise from influential figures like fellow Philadelphian Tom Lax. After an initial run on Gulcher Records, the album was reissued by Woodsist, the newly prominent imprint run by members of the band Woods. The following spring another hot new label, Mexican Summer, put out a second LP called God Is Saying This To You... collecting a few years' worth of home recordings. By the end of 2009 Vile had signed to Matador Records, one of the most storied labels in indie rock history, and released his first proper Violators record Childish Prodigy. He was suddenly a known quantity, and with Smoke Ring For My Halo, he leveled up once again.

It may well be Vile's best record, but in hindsight Smoke Ring For My Halo feels like a transitional release, a bridge between the scuzzy lo-fi recordings of his underground era and the more professional phase that began with 2013's blissed-out Wakin On A Pretty Daze. Think of it, maybe, as the darkness before the dawn. Vile had long been messing around at the intersection of many interconnected sounds: Delta blues, Fahey-esque folk, outlaw country, bleary post-punk, murky basement lo-fi, the fuzz on the FM dial just a few decimal points away from your local classic rock station. He had developed an unmistakable personal style -- a heartland rocker for the WFMU set, a troubadour spinning sidelong koans alongside head-blown experimental rock bands -- and that style was in the process of becoming brighter and more accessible. But for now, it remained in shadows.

Whereas Vile had produced Childish Prodigy with Granduciel and Philly mainstay Jeff Zeigler, he and the Violators did Smoke Ring For My Halo with John Agnello, the longtime indie rock producer who had recently struck up fruitful partnerships with the likes of Sonic Youth, the Hold Steady, and Dinosaur Jr. The last association was especially relevant considering how much Vile's laconic drawl resembled J Mascis, though Vile's own guitar heroism had little to do with Dinosaur's charred proto-grunge. Vile was less about sludgy power chords and ripping solos than fingerplucked tapestries, bluesy string bends, and echo-laden strums. Agnello helped those sounds to glow without scraping off all of the filth, sculpting a sound both gnarled and dreamy.

With that in mind, central to the album's appeal are a series of trancelike acoustic numbers that function as the baseline of Vile's sound. Side openers "Baby's Arms" and "Runner Ups" both exist in this form, as do deep cuts "Peeping Tomboy" and "Smoke Ring For My Halo" -- minimal to no percussion, an acoustic guitar riff on loop, Vile uttering plainspoken profundities about a woman's love and the workingman's plight. Much of the rest of the album builds out on that template, beefing up the rhythm section and/or laying on the holographic sheen. Even at its loudest and heaviest, when Vile's placidity brushes up against the hopeless and sinister, Smoke Ring For My Halo never loses his signature languid grace, a state of stoned enlightenment that lends even his simplest remarks an air of depth and wisdom. Sometimes the results are peppy and propulsive, as on "Jesus Fever" and "In My Time." He taps into a Stones-like swagger on "Puppet To The Man," while the blustery "Society Is My Friend" feels like a Tom Petty song that might blow away at any moment if not anchored by such hard-smacking drums.

The album's peak is probably the drowsy sprawl "On Tour," beautified by harp from a pre-fame Mary Lattimore even as Vile sketches out the dark side of a life spent traveling the country one seedy rock club at a time. Over the course of five minutes, the typically chill Vile sketches out a tense and paranoid headspace plagued by the kinds of unsavory characters that dot the live music landscape. "Watch out for this one/ He'll stab you in the back for fun," he remarks. "I'm just playin'/ I know you, man/ Most of the time." Before waves of guitar noise kick up and the song roars to its conclusion, Vile presents music as a means of catharsis, a therapy that justifies putting up with all the showbiz treachery: "I wanna write my whole life down/ Burn it there to the ground/ I wanna sing at the top of my lungs/ For fun, screaming annoyingly/ Cause that's just me/ Being me, being free." It's a thrill, but the explosiveness is a bit out of character for Vile. Not until closing ballad "Ghost Town," a song suspended between lucidity and disintegration, does he perfectly crystallize this album's vibe. "In the morning I'm not done sleepin/ In the evening I guess I'm alive."