- XO

- 2011

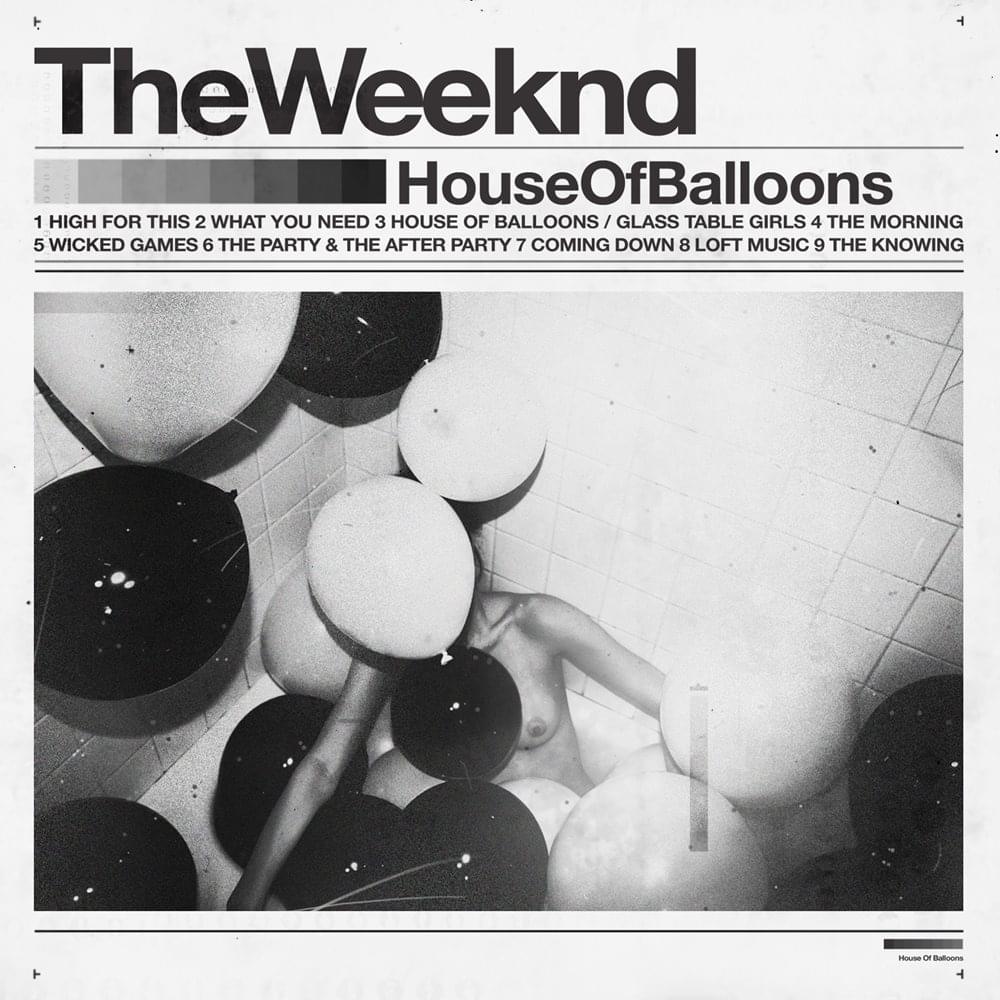

The Weeknd must have been genetically engineered by music bloggers. Not the current, chart-topping, Pepsi Super Bowl Halftime Show-performing version of the Weeknd, but the Weeknd of 2011, who sang like a siren beckoning listeners to smash into the rocky crags of depravity, whose identity was such a mystery that some journalists were still referring to the Abel Tesfaye solo project as a "group" the following year.

His debut mixtape, House Of Balloons, was released 10 years ago this weekend. At that time, for the Extremely Online music fan, it felt like the perfect hype storm. The early 2010s were a boom time for drooling over performative anonymity, as well as making a big fuss about hybridizing indie music and R&B, two things the Weeknd did expertly from day one. The skeevy American Apparel/Terry Richardson aesthetics of his single and mixtape art, the Beach House samples, the idea of taking The-Dream's darkest, weirdest impulses even further down the rabbit hole, the Drake cosign -- there's no way to overstate how en vogue it all was. In the words of Sam Elliott's Big Lebowski opening monologue, "Sometimes, there's a man... Well, he's the man for his time and place. He fits right in there." In the words of a House Of Balloons song, "He's what you want, I’m what you need."

The buzz all started with some posts on Drake's OVO blog, first by manager Oliver El-Khatib in December 2010, then by Drake himself in early 2011 (yes, blogging was that popular, and yes, Drake used to do normal human stuff). That's how most of the world got the first four Weeknd songs ("Loft Music," "The Morning," "What You Need," and "Wicked Games"): accompanied by little more than an "INTRODUCING THE WEEKND" caption and a photo of Tesfaye in a dark hallway, face mostly obscured by shadow. Let the music speak for itself is one way to explain this rollout method; the hindsight cynicist in me reads it more as, This music's darkly intriguing, we'll let you imagine that the guy who made it is too.

Perhaps inviting listeners to use their imaginations added something. You could envision the scenarios described in all four of those early tracks unfolding in the same location, a seedy-but-well-furnished apartment that housed no permanent residents -- a party pad with dim, reddish lighting and Himalayan piles of cocaine on every horizontal surface, all of which are made of glass. It’s a loft where the walls kick like they're six months pregnant, where women call cabs at dawn and forget their high-heeled shoes. Leave your girl back home.

See? That’s a lot sexier than a broke, 21-year-old American Apparel employee's reality.

"This was still a time when 'enigmatic electronic producer' was a phrase you'd find in every other track blurb," Ian Cohen recently observed when looking back on Love Remains, an album by similarly "mysterious" artist How To Dress Well that was released five months prior to House Of Balloons. The guy behind that project, Tom Krell, maintained anonymity from October 2009 to April 2010, when Pitchfork sniffed him out for a Q&A. Lest we forget the Residents, Slipknot, Buckethead, Daft Punk, MF DOOM, Burial, and a whole host of other predecessors, concealing appearances and/or identities was nothing new in 2010, but something about that blog-heavy, pre-streaming era birthed a bum rush of fully- to semi-anonymous artists making their names on trendy websites.

The name of the band "Unknown Mortal Orchestra" was still literal when their first tracks appeared in May 2010 on an otherwise unlabelled Bandcamp page. Self-mythologizing UK collective WU LYF first popped up the same month, and reviews of their first and only album the following year are ripe for a drinking game centered around the words "mysterious," "shadowy," "intrigue," and amid less breathless praise, "posturing." Sia started hiding her face onstage in fall 2010. 2011 saw SBTRKT and his omnipresent masks blow up. 2012 brought us the momentarily entertaining guessing game "Who is Captain Murphy?" before Flying Lotus pulled back the curtain. I'm sure I'm forgetting some glaring examples, but suffice it to say the early 2010s was one of the few moments in music history in which obscuring your identity was the savviest marketing strategy available.

I'd love to parse out why that was the case -- privacy and un-Googlabilty looking real attractive in the final days before social media's complete blanketing of society? A more cyclical, "this happens every 15 years" explanation? -- but my point is that the Weeknd's timing for his camera-shy bit couldn't have been better. After explaining his aversion to being photographed in his first-ever interview in 2013, Tesfaye elaborated on his marketing strategy: "The whole 'enigmatic artist' thing, I just ran with it. No one could find pictures of me. It reminded me of some villain shit."

He was certainly playing the villain in his songs. House Of Balloons opens with Tesfaye telling a woman, "We don't need no protection," before cooing, in a sickly-sweet voice over dubsteppy synth bass, "Trust me girl, you wanna be high for this." It spirals out of control from there. On "The Morning," he pines for night's return because it's the "only place to find baseheads and hot women." On "The Party & The After Party," all of that coke-fueled opulence turns sinister: "I got a brand new girl, call her Rudolph/ She'll probably OD before I show her to momma." Even when he deigns to show emotion, as he does on "Wicked Games," it's raw and menacing: "Bring your love, baby, I could bring my shame/ Bring the drugs, baby, I could bring my pain."

Perhaps because he was making the darkest R&B imaginable, the anonymous approach worked better for him than it did for psych-pop bands, anthemic indie bands, chandelier-scraping belters, voiceless electronic musicians, and electronic musicians who probably should've remained voiceless. Anonymity also suited the Weeknd's creation of a persona. Like Tyler, The Creator, who perhaps not-so-coincidentally was blowing up around the same time, Tesfaye's brash lyrics were very obviously a put-on, no matter how shocking or aspirational they got. The laundry list of drugs consumed in "House Of Balloons/Glass Table Girls" gives the preposterous smoothie from the "EARL" video a run for its money; the $7,000 glass table name-dropped in the same song was probably a little out of his price range at the time.

Unlike much of Tyler's early music, House Of Balloons holds up because its aesthetic is just as carefully sculpted as the character Tesfaye's playing (the absence of violent rape jokes doesn't hurt either). Tyler's Goblin, released two months later, wildly ping-pongs between aggro noise-rap, Neptunes worship, and queasy jazz chords. House Of Balloons, helmed by a producer trio that includes two Weeknd mainstays (Doc McKinney and Illangelo) and one who allegedly got "majorly screwed" (Jeremy Rose), combines similarly eclectic influences -- '80s goth rock, dour downtempo electronica, dream pop, chopped-and-screwed Houston rap, to name a few clear signposts -- but never lets them distract from its chief musical goal: a druggy, nocturnal vibe. Tyler was still trying on various hats; the Weeknd arrived with one glued to his skull.

"The Beach House and Siouxsie And The Banshees samples on House Of Balloons worked musically," wrote Stereogum’s own Tom Breihan in 2012, "but they also sent a message -- dorks like us would have to take [the Weeknd] seriously." The full list of the mixtape's sampled artists -- which also includes Cocteau Twins and, on the original version of "What You Need" that's finally being re-released this weekend, Aaliyah -- was a dream come true for everyone who spent the previous year freaking out about Kanye's Aphex Twin sample, James Blake's Aaliyah/Kelis sample, and/or Tyler's Liars sample. For the omnivorous listener, hearing two disparate genres brush up against each other in ways you’d never previously imagined is a treat akin to watching Danny Devito and Arnold Schwarzenegger pal around in Twins.

There was a lot of that going on in the early 2010s -- perhaps no more so than any other era, but all of it seemed to be getting attention. Death Grips made everyone forget that hip-hop had ever previously brushed shoulders with punk, noise, and metal -- ditto for Sleigh Bells with regards to pop music. Liturgy and Deafheaven's radical updates on black metal put the genre in conversation with shoegaze and other "hipster" fare. It-producers of the moment AraabMuzik and Clams Casino churned out cutting-edge rap beats that owed just as much to trance and ambient music, respectively, as they did to hip-hop.

The Weeknd's skillful genre play and savvy sample choices reflected a larger movement of predominantly Black pop/R&B artists engaging with predominantly white indie pop/rock music, and vice-versa. The xx, Frank Ocean, How To Dress Well, James Blake, Miguel, Holy Other, Solange, Dirty Projectors' "Stillness Is The Move," Usher's "Climax" -- all of this stuff was slapped with a genre tag involving a certain hipster-associated cheap beer brand that I promised myself I wouldn’t mention in this piece. Most early coverage of this trend implied that R&B had never been "weird" or "alternative" before, ignoring the forward-thinking work put in by more entrenched artists like Janet Jackson, Brandy, Kelis, and yes, Aaliyah, in years prior, usually without the input of white collaborators. The racism was inherent. It shouldn't take away from any of the music itself, but in 2011, every buzzy artist had to seem as fresh or as innovative as possible, even if it meant ignoring the past.

Just over a month before House Of Balloons' release, Frank Ocean put out his own debut mixtape, Nostalgia, Ultra. The parallels abound -- recognizable samples of indie/alternative music, casual drug references, the creators' commitment to remaining elusive and behind-the-scenes -- but in the years since, Tesfaye and Ocean have been on opposite trajectories. Nostalgia-era Ocean, with his brighter music, Coldplay and MGMT samples, and slightly bigger media presence (whereas Tesfaye wouldn’t give his first interview until 2013, Ocean was on a Fader cover by the end of 2011), seemed much more primed for the spotlight than the more dour, less family-friendly Tesfaye. But while Ocean receded further and further into the shadows and released commercially unsuccessful, critically adored albums, the Weeknd improbably became one of the 2010s' biggest success stories.

House Of Balloons was the first installment of a mixtape trilogy, all of which arrived by the end of 2011. After working on his debut for years (and gifting a few cuts from its planned tracklist to Drake for his 2011 album, Take Care), the Weeknd rushed to release a follow-up. "There are lyrics on Thursday, I don't even know what the fuck I said," he quipped in that aforementioned 2013 interview. It showed. The tape has all of its predecessor's haziness and very little of its punch. The two subsequent releases -- the trilogy-capping Echoes Of Silence and lush 2013 debut album Kiss Land -- also lack in areas that House Of Balloons triumphed, namely a consistent, impeccably-curated vibe. But looking back I'd call them the Weeknd's most underrated material, victims of not sounding enough like the breakout tape. Kiss Land did well for itself commercially, debuting at #2, but as far as hits go, this still wasn't Pop Star Weeknd. None of the singles even sniffed the Hot 100.

After excitedly covering the Weeknd's earliest music at my first-ever blog gig in Spring 2011, I vividly remember the turning point, the day in May 2015 when "Can't Feel My Face" and "In The Night" leaked. In between Kiss Land and that leak, singles "Often" and "Earned It" had hinted at a more pop-friendly Weeknd, but not like this. Both new leaks were co-produced by superproducer Max Martin, and sounded like it. I knew "Can't Feel My Face" was a lock for the charts as soon as I heard it, and I'm no Hot 100 Nostradamus. It was as obvious a hit as they come, even despite its subject matter. It went #1 a few months later.

The Weeknd's never really let up since then. "The Hills" was even bigger than "Can't Feel My Face," 2016's Starboy had yet another #1 with its title track, and last year's "Blinding Lights" is one of the most successful singles of all time, recently becoming the first-ever song to spend a whole year in the Top 10 of the Hot 100. Tesfaye's now big enough to play Super Bowls and raise a justifiable stink about a Grammys snub. No matter how smitten you were with "What You Need" the first time you heard it, there's no way you could’ve predicted a fraction of these achievements.

How did it happen? How did an X-rated lothario, whose live debut in the US (at Coachella 2012) earned mixed reviews, make his way to the biggest stages in the world? For one, he's toned down his content considerably since his “Or Nah” remix days -- the most eyebrow-raising part of his last album is an extended bit about having sex in his recording studio, and save for a couple of really gross bars, he’s steered clear of major controversy (just don’t ask stan armies). The singles have gotten poppier; his performance chops, while still not god-tier, have improved. Tesfaye's path to success was unlikely, but easy to chart in increments.

What's more impressive and surprising, to a day-one fan, is the Weeknd's never-ceasing commitment to self-curation and aesthetic specificity. That's why the weirdo impulses -- the whole red suit thing, the partnership with Oneohtrix Point Never, etc. -- persist, but it's also a masterclass in modern star-making. Anonymity may have been the marketing tactic du jour a decade ago, but more often than not, it's hollow and unsustainable. What the Weeknd's done is turn himself into a moodboard of his favorite directors, musicians, vibes. He began that process in auspicious form on House Of Balloons, and while he may have covered a ton of ground to get to where he is in 2021, the self-mythologizing is still going strong. He's still lying about the nights, hiding it all behind smiles. 'Til the ending of the credits, life's such a movie.