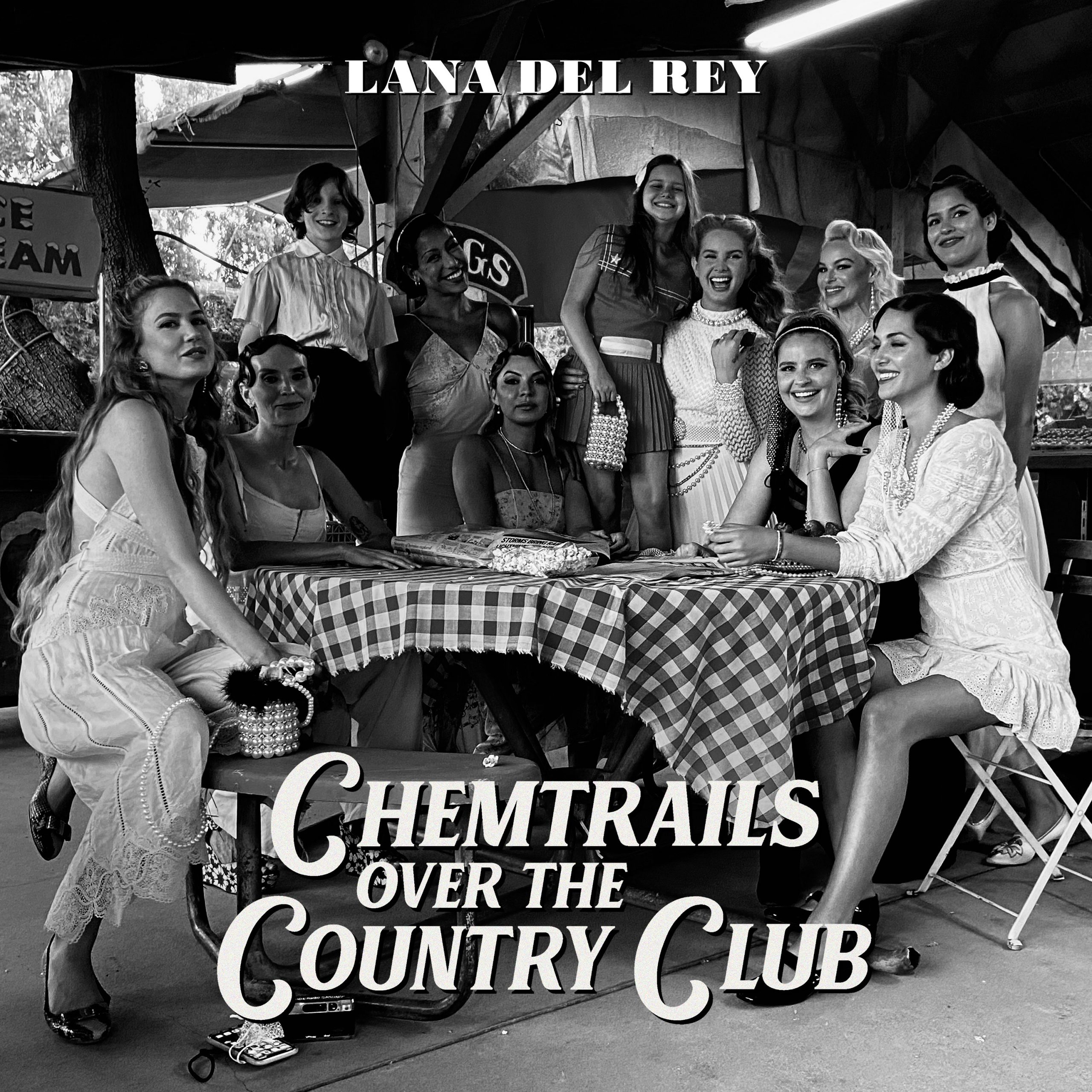

- Polydor/Interscope

- 2021

You could hear it coming from miles away, like the rumble of an approaching train. The sound was a dull thrum back when the rapturous reviews of Norman Fucking Rockwell! (including our own) began arriving. It got louder with the Grammy nominations and the high placements on year-end lists (again, including our own). That noise surged in volume around the time of "question for the culture" and "thanks for the Karen comments tho." When Lana Del Rey wore the mesh mask to the book signing, it was deafening.

"Backlash" isn't the word for that sound. "Backlash" doesn't cover it. Lana Del Rey has been through backlash plenty of times before. This is something else. Sometimes, an artist will do enough insufferable things in a short enough period of time that a certain reaction becomes inevitable. When an artist follows a massively praised work by being publicly annoying, then the goodwill from that massively praised work can go away real quick. Ask Arcade Fire. Ask Chance The Rapper. A new Lana Del Rey album is a no-win proposition. Lana Del Rey already made sure of that.

Sometime in the past year, at least in the corner of the internet that I unhappily occupy, "oh, fuck this" became the general-consensus reaction to anything that Lana Del Rey said or did. Every public statement came off as some clanging combination of fake-profound and defensive. Every new post was a reaction to the reaction to the last post, an infuriating feedback-loop. Almost immediately, I saw people fuming about the critical love that Normal Fucking Rockwell! had racked up. As I came to dread every new Lana Del Rey blog post I'd have to write, I started to question my own love of Norman Fucking Rockwell! Did I get caught up in something? Is Lana Del Rey just bad?

Short answer: No. Norman Fucking Rockwell! ruled in 2019, and it rules today. That album's lush, psychedelic sweep and acid-tongued swagger continue to ring bells. Norman Fucking Rockwell! is a titanic achievement and a tough act to follow. Chemtrails Over The Country Club, Lana Del Rey's follow-up, is nowhere near its equal, and that seems to be by design. Where Norman went for gurgling, acid-fried apocalyptic electric-guitar grandeur, Chemtrails is a soft shrug of an album, a low-stakes wisp of a thing.

You can hear it in the instrumentation. Jack Antonoff, Del Rey's extremely busy Norman Fucking Rockwell! collaborator, returns on Chemtrails Over The Country Club. Antonoff produced all but one song on the new album, and he co-wrote most of them, too. Antonoff also plays just about every instrument on the record, acting as one-man studio band. But without a credit sheet, Antonoff's touch isn't much evident on Chemtrails. The new album doesn't sound like the work of the same people who made Norman Fucking Rockwell! It's slighter and smaller, mostly built around tinkly pianos and lightly brushed drums.

On Chemtrails, Del Rey often sticks to her upper register, which gives her voice a whispery and frail kewpie-doll quality. Where her softest vocals still sounded rich and textured on Norman Fucking Rockwell!, the Del Rey of Chemtrails sounds weaker and shallower. That voice blurs into the background a little too easily, and you can hear the Auto-Tune on it a little too often. (That Auto-Tune is a deliberate aesthetic choice, not an attempt to cover up for anemic vocal performances, but that doesn't mean it's the right deliberate aesthetic choice.) More importantly, the songwriting, by and large, is nowhere near as muscular as it was two years ago. Norman Fucking Rockwell! was an album. Chemtrails Over The Country Club feels more like a collection of vibes.

For Lana Del Rey, this isn't new. Chemtrails is Del Rey's sixth album in a decade, and it fits right in with Honeymoon and Lust For Life, the records where Del Rey is content to luxuriate in her own languid splendor. Like those albums, Chemtrails is a pleasant-enough sunny-afternoon reverie -- the kind of album that manages to be pretty and boring at the same time. A few songs, like the early single "Let Me Love You Like A Woman," capture some of the soft-focus majesty of Del Rey's best work. A few arrangements, like the loping hippie funk of the second half of "Dance Till We Die," find subtle new wrinkles on Del Rey's long-established house style. Most of the time, though, Chemtrails blinks quietly in the background. It's a pretty-good record of loungey torch songs from an artist capable of so much more.

The Lana Del Rey of Chemtrails Over The Country Club still has bars, but her lyrics have taken a different form. None of the lyrics on Chemtrails burn as righteously as "your poetry's bad and you blame the news," but that's not what she's going for here. Instead, on Chemtrails, Del Rey taps into her affection for the mythic Americana that's inspired basically all of her recorded music. The album's title feels like a classic doomed-beauty bait-and-switch -- the place of idyllic moneyed conformity, poisoned by the imaginary mind-control agents that have come to represent so much to so many profoundly lost people. But from the album's lyrics, it's clear that Del Rey is a lot more interested in the country club than in the chemtrails. And she likes the country club. She thinks it's a fun place.

On the title track, Del Rey sings about the country club as an idealized oasis of domestic bliss: "It's beautiful how this deep normality settles down over me/ I'm not bored or unhappy, I'm still so strange and wild." She's in her jewels in the swimming pool, drag racing her little red sports car, contemplating God. On "Let Me Love You Like A Woman," she bathes in the warmth of tradition and submission. She's from a small town; she only mentions it because she's ready to leave LA and she wants you to come. More than once, she sings that she no longer wants to be a candle in the wind. The whole album works as a hymn to some mythic idea of stability. This doesn't seem like an ironic put-on. It seems like a sincere longing for a state of being that may not exist.

The album also works as a hymn to American music from bygone eras. On "Breaking Up Slowly," Del Rey and Nikki Lane, the Americana singer who co-wrote the song with her, invoke the spectres of George Jones and Tammy Wynette, using them both as a totem and a cautionary tale. Lane doesn't want to end up like Tammy Wynette, as Del Rey warns that "George got arrested out on the lawn." Del Rey even lets a little fake twang creep into her voice. (She can't fool me; I've been to Lake Placid. Motherfuckers in Lake Placid talk like they're Canadian.)

On "Dance Till We Die," Del Rey namedrops the singer-songwriter greats that she's come to know, and she sounds a little like the Game constantly mentioning Eazy-E: "I'm covering Joni and I'm dancing with Joan/ Stevie is calling on the telephone." Most soberingly, on opener "White Dress," she applies that same idealized nostalgia to the early-'00s rock revival: "Listening to Kings Of Leon to the beat," "Listening to the White Stripes when they were white-hot." She might as well be talking about the Beach Boys again.

Two years ago, Lana Del Rey made an album that can hang with just about anything from the idols whose names she sings so lovingly. Chemtrails Over The Country Club is not that. Instead, Chemtrails is a small, hushed, pretty little record. The album reaches its peak as it ends, when Del Rey really does cover Joni. Del Rey and guests Zella Day and Weyes Blood sing "For Free," the 1970 song where Joni Mitchell marvels at the beauty of some guy playing a clarinet on a streetcorner while she's out shopping for jewels. The three of them sang that one onstage in 2019, when Del Rey was touring behind Norman Fucking Rockwell!, and the video of them rehearsing made for a lovely, ephemeral, inessential internet moment. In its proper recorded form, the trio's "For Free" works in much the same way. I hope the rumble doesn't drown it out.

Chemtrails Over The Country Club is out now on Polydor/Interscope.