Attending an alternative elementary program in Los Angeles known as the Open School in 1995, a 10-year old Ermias Joseph Asghedom had developed a knack for creative writing, one that his teachers underestimated even though a few of Asghedom's classmates would copy from his work. Asghedom's writing skills transitioned from short stories to free verse poetry, but despite his readiness to join the school's initiative for gifted students, he was shunned by a teacher who said students had to be selected for consideration. Once notified about her son being rejected, Asghedom's mother Angelique Smith visited the Open School, demanding that her son be tested for the program. Asghedom well surpassed the program's criteria, a message of opportunity meeting preparation that would trail him for the remainder of his life as he evolved into the revolutionary rapper, activist, and entrepreneur Nipsey Hussle.

Akin to his enthusiasm for writing, Hussle was also an avid reader. Following his tragic murder in front of Marathon Clothing in South LA on March 31, 2019, fans eulogized the 33-year-old by compiling lists of his favorite books. As lists went viral, it provoked the idea for The Marathon Book Club, an intimate space for fans -- largely minority and male -- to attend weekly readings in dedication to the artist's legacy.

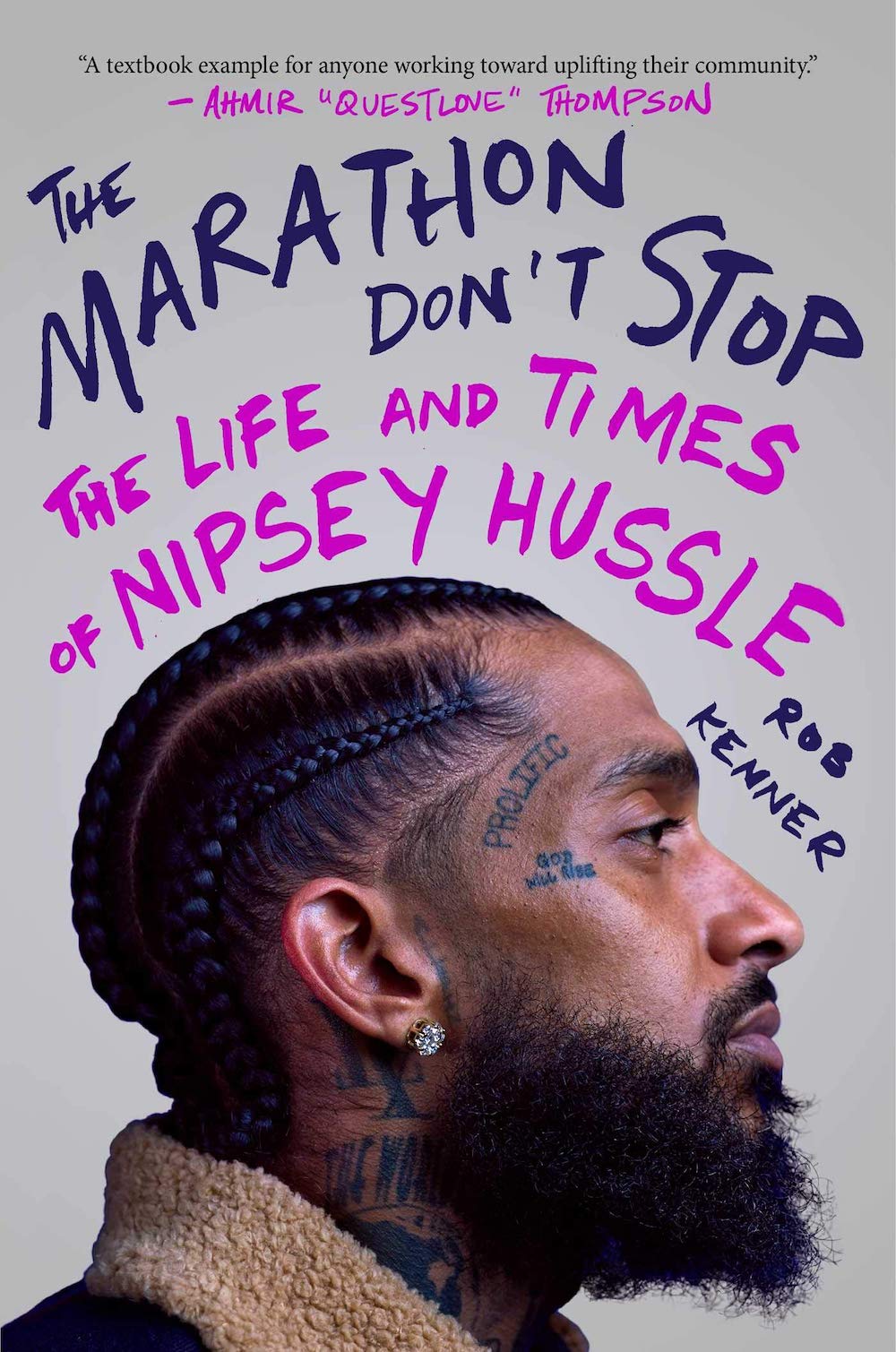

Ten years prior to Hussle's death, Vibe founding editor Rob Kenner met the rapper at the magazine's New York office just as Hussle was on his rise to breakthrough fame. Without a label backing him, Hussle was still determined to be featured in the magazine's Next section, where artists like Outkast and Mary J. Blige were discovered on a mainstream scale. Kenner and Hussle remained in touch throughout the years, last connecting during a promotional interview with Mass Appeal before the 2018 release of Victory Lap, Hussle's debut album. Fascinated with Hussle’s energy and level of consciousness throughout his career, Kenner’s idea for his new book The Marathon Don't Stop was birthed, a retracing of Hussle's life, purpose, and intentional vision for his community.

Ahead of today's release of The Marathon Don't Stop, we spoke with Kenner about Hussle’s love for hip-hop, the rapper’s life-changing trip to Eritrea in 2003, and the fulfillment of his life mission.

Congratulations on the book! It's like the Nipsey Hussle Bible.

ROB KENNER: Oh, thank you. I'm honored to hear you say that. I know that Nip was an avid reader and people have formed book clubs in his honor. I'm hoping that this book will be worthy of inclusion on one of those reading lists.

Have you spoken to anyone who organizes the book clubs for him?

KENNER: There's actually someone who I've recently gotten in touch with since we started really promoting the book in the final weeks until release. They said they've started a book club just because of this book, which I thought was very flattering. I like to feel as though this is furthering the goals and intentions Nip had in his life.

There's a lyric that we quote in the book: "When it's over all that counts is how the story is told/ So write my name down, write my aim down." Nip is obviously a singular figure in hip-hop history, and if you care about hip-hop, you care about Nipsey Hussle. It's just shocking to think that during his lifetime there were very few decent magazine profiles. Apart from the GQ piece, which focused on his relationship with Lauren [London], there was not a decent in-depth profile of him. So that’s what I tried to contribute in The Marathon Don't Stop -- it's just putting his life in the proper context. Hip-hop history in American history.

Why do you think it was that he didn't have a lot of articles or features written about him? Do you think it was because of how powerfully he spoke? That people wanted to record him more than write about him?

KENNER: I think that he definitely saw the direct connection to his fans. Being very tech savvy, he recognized the power of social media very early and became very comfortable on camera. As you read in the book, he was surrounded by the ButterVision crew early on and [ButterVision founder] Dexter Brown has not really been part of Nipsey's narrative publicly. I haven't seen him interviewed anywhere before this book. Dexter is a prolific photographer and videographer. He was very focused on teaching all of the young people in his circle about media, how to speak on camera and how to get your message across. I think that's why Nipsey never turned down an interview.

There are so many brilliant interviews with him on YouTube and that was an important resource for me and putting the book together. What I learned was that even if you think that a random, obscure video is not worth watching because the same topics have been covered in another video, he always found some other detail. There was always one new thing in every interview, even if it was a narrative that he’s told in some way before.

In terms of magazine profiles, that's more when you're signed to a major label when the PR team is pushing the album release. As we know, for a lot of his career, he was just completely independent. The mixtapes would come out and he would just speak directly to his fans over the camera or a cell phone. Whatever means necessary, he would get the message out. For me, it was just a question of gathering all these voices together and trying to present a coherent narrative of his life and just show why he was such a singular figure in hip-hop history.

You compiled a lot of information on Nipsey's career, from his upbringing to the complex history of South Central LA. What was the process of writing the The Marathon Don't Stop?

KENNER: Well, the beginning was speaking with Nipsey Hussle. I had the chance to meet him very early in his career when he was rolling out the Bullets Ain't Got No Name mixtape series. He came up to Vibe Magazine in 2009 and I learned later that he had been submitting demos to Vibe's Next section for new and emerging artists. Nip as an unsigned rapper from LA was sending his own demos and headshots for several years before he made it up to the office. Dexter Brown told me that he was disappointed that he wasn't hearing back from us for a while, but as with every other goal that he set for himself in his life, he continued to persist despite early setbacks.

So he made it up to Vibe and he was playing us his tape. I was very impressed with the music, but even more impressed with just his energy and his demeanor -- he was a very powerful individual. I spoke with him after that listening and encouraged him to keep going and that we would support him however we could. We ended up running a one page profile in one of the last [physical] issues of the magazine before the magazine actually folded.

I paid attention to him over the course of his career at other places where I was working, like Complex. There was an incident where one of our staff members reached out to Nipsey requesting an interview. We had done a list that sort of threw a little shade on Nipsey shortly before Crenshaw came out and he didn't think it was very cool for Complex to be asking for an interview after we had listed him as one of the underachieving rappers. So he tweeted Complex and I encouraged my colleagues behind the scenes to press ahead, and do the interview and let him say whatever he wanted to say.

All of these things fed into my interview I had with him when he was doing the Victory Lap roll out. A few days after the album release, I had a chance to speak with him for about an hour. It was just one of those interviews that was more than a Q&A, it was a conversation. I think a lot of people who have the opportunity to speak with Nipsey had this experience where the ideas that he exchanged with me were so powerful that it really changed the way I looked at my own life and my work. The book really was born at that moment. I began to gather my material and reach out to some of the people who have worked with him. This was prior to the tragedy of March 31. I was aware that I wanted to do something bigger with Nip.

As things unfolded, the whole world started paying more and more attention to him after his passing. There were a lot of people that were just catching on to him and didn't understand why he was so important. Why did he have this nationally televised memorial at the Staples Center? He was the only artist besides Michael Jackson to have that kind of a sendoff. An artist who -- to some people -- was just an underground mixtape rapper. This was an important story to tell for lots of reasons.

While conducting research for the book, was there anything that you were surprised to discover about Nipsey?

KENNER: So many things. One of the things that surprised me was how early he knew he wanted to be an artist. The perception that you often heard was that here's this guy from a tough neighborhood in LA, he's really in the streets -- but long before he was involved in street life, he was in love with hip-hop. He talked about when Kriss Kross dropped the record "Jump" -- he wanted to be a child rapper. I love the fact that he just loved hip-hop, you could never get him to diss another artist.

The rap media will try to bait people into talking shit about other rappers and Nip would never take the cheap shot because he just felt like, if you are finding a way to feed your family and make a living through this art form, then more power to you. Nip tried very hard to not bash other rappers and it's because he loved the art form. I learned [while writing] the book that he was flying out of state to perform at the invitation of Afeni Shakur before he was even known as Nipsey Hussle -- he was known as Concept. People need to know and really understand how deep his love for hip-hop was.

This label that people throw around, "gangsta rapper," is kind of a tired mass media hysteric title. I tried to unpack what's behind the history of gangs in LA and how Nip was trying to bring these neighborhood organizations back to their original purpose of protecting and empowering communities that have been under siege. I could go on and on, but there's a lot of things in the message of his life that America needs to tap into and understand right now.

In the book's opening, you mentioned that music received a 2,776% spike in sales. Why do you think that people become invested in an artist's music after they've passed?

KENNER: It's just one of the bitter ironies that he did not receive his flowers while he was here to appreciate the love. He had a respectable debut with Victory Lap, he was Grammy-nominated and he won two Grammys posthumously, but I think that New York radio didn't really embrace Victory Lap like they could have early on. Some of the tastemakers didn't quite "get it" the way they should have. Even when he did some of the big radio stations [in New York] to promote it, it was clear that not all of the DJs were very familiar with his catalog.

People who have been tapped in with Nip for a long time were very familiar with the whole story, the Crenshaw mixtape, the brilliant insight of selling a physical copy for $100 along with merch and a ticket to a private concert. That's a marketing gimmick that has now been adopted by the entire music industry. This idea of the deluxe bundle that artists like Justin Bieber and Taylor Swift are all doing now to get number one SoundScan placements, but Hussle came up with that idea. That is his blueprint that other mainstream acts are following. The world just caught on late, they slept. He was a slept-on artist in every sense of the word, it's sad.

I'm happy that Nipsey's family will benefit from all those streams, and because Nip controlled his assets, they're gonna reap the lion's share of the profits, which is awesome and a testament to his vision. It would have been nice if he was able to enjoy those accolades while he was here.

Due to the impact of "FDT" with YG, it was apparent that Nipsey had a political acumen. If he were still alive, what do you think his role would have been during the Black Lives Matter movement?

KENNER: I really thought about that all through writing the final stages of the book, which was completed during the pandemic lockdown and the racial reckoning in this country. It gave me strength to work around the clock tirelessly to complete this book and make sure his voice would be heard at this time. I feel like America and the rest of the world are on a tipping point where things could go either way. In January, we literally had a military coup attempt to overthrow the United States government and it narrowly missed succeeding.

Two so-called gangster rappers from LA from different neighborhoods that were supposed to not get along came together to point the finger at a presidential candidate at the time and say, "This guy is trying to divide this nation." We're coming on the five-year anniversary of "FDT" and the record has become an anthem. It had a huge spike on Election Day. I believe it is part of the reason why there was such a strong voter turnout; it became an anthem for the resistance.

What Nipsey would be saying right now? He would be doubling down on "Fuck Donald Trump" and fuck racism and fuck divison -- let's bring the streets together, let's bring the world together. He listed Bob Marley as one of his favorite artists of all time. I believe that although their sound is very different, Nipsey was very much about the concept of one love. He was bringing together the streets of LA, bringing together brown and Black listeners on "FDT," and he even did the remix with G-Eazy and Macklemore. That's what hip-hop has been all about at it's best; uniting people of like minds to go against hypocrisy and outmoded ways of thinking. He would be right there at the forefront of the conversations that are going on right now. Even without his physical presence, his voice is very much being heard.

You connected Nipsey with Alprentice "Bunchy" Carter of the Black Panther Party in the book. In what ways did their lives intersect?

KENNER: I was impressed by how Nip was claiming the Slauson Boys, a street organization in Los Angeles that predated the Black Panthers moving into LA. Bunchy was the head of the Slausons and he ended up being recruited while he was actually doing time on a robbery charge, but he was incarcerated with members of the Panthers. They said, "We need someone like you to open the LA branch of the Panthers," which started in Oakland and had a strong outpost in Chicago and other places. Bunchy became that person [who] expanded the Panthers into LA and very quickly was on the radar of the FBI.

Herbert Hoover identified the Panthers as the single greatest threat to America, so there's a lot of speculation about why [Bunchy] was killed. We know that there was a COINTELPRO program that was backed by the FBI and thought to be stabilized. The the murder of [Bunchy] was on the campus of UCLA, but it has always been alleged that there was some forces behind the scenes that brought this conflict out.

Nothing has ever been proved, as with the murder of Malcolm X. We've recently seen a film that very clearly connects law enforcement and FBI to the execution of Fred Hampton. So there's an ongoing narrative that Black leaders who rise up, cause people to come together and try to move the cause of justice forward, are targeted by the authorities. Although there's been very little investigation into the surrounding forces of Hussle's murder, there was one arrest made -- but the larger questions remain.

I made a strong effort to focus this book on Nipsey’s life and his legacy more so than the murder and getting too bogged down into the tragedy and making it like a murder mystery. It's a tragedy and it's an outrage, but the work of his life needs to continue, and his message needs to be heard.

If it weren’t for his trip to Eritrea in 2003, do you think he would have gained an intentional vision for his career and community upliftment?

KENNER: I know that he described it as a life-changing experience when I spoke with him and in other interviews, as well. It was a trip that his father strongly believed was necessary. Both [Nipsey] and his brother had grown up in Los Angeles their entire life and their dad wanted them to connect to the East African family and culture. Nip was a little reluctant to leave LA for three whole months, he was not sure if he really needed to be away for that long. He had a lot of business that he was trying to tend to at the time and didn't want to spend so much time away. It completely changed his worldview, just to be in a country where family is so important.

Being in a country where the government were all Black folks -- just innumerable things that he learned on that trip. When he came back to LA, the people who knew him from before noticed the difference, just that he had even more of a focus and sense of purpose of what he was trying to do. It was around the time that he started talking about this idea of a marathon. And, you know, I love the fact that when he was in Eritrea, he would go to a local record shop and [say], "I'm gonna be a big rap star, one day you're going to hear about me." He would play his demo in Eritrea, and just the idea of that is very powerful.

As you know from reading the book, he did, in fact, return to his father's homeland after he had become a big rap star. [He] met with the president [and] gave an interview with the main newspaper in the country. That is just a powerful, powerful image [and] reminds me of Malcolm X's trip to Mecca, in a sense -- just this idea of a pilgrimage that changes everything.

Listening to Victory Lap at the time of its release versus now, how has the sound changed for you? It seems like it was divine timing that the album was set back for 10 years until the year prior to his death.

KENNER: The record definitely has definitely aged very well like fine wine -- it becomes richer over time. When you listen to some of the tracks now, they hit even harder and in different ways than when we first heard them. The song "Real Big" played at his memorial service as [Nipsey's friend and business partner] Rallo told me when I spoke with him, he couldn't bear to hear it -- he had to leave the auditorium just thinking about how he summed up their experiences.

[For Nipsey] to have life taken away at the moment when things were just about to level with Roc Nation managing him... They were about to start touring only arenas. Nip was about to go on executive producer mode on projects for his protégés, he was getting ready to bring up the next wave behind him. To have it all snatched away, it's brutal -- this is still a very painful story for people to revisit.

There's a lot of love, a lot of reverence on Nipsey's legacy in Los Angeles and around the world. I felt a strong responsibility to tell this story with the utmost love and respect. I hope that when people read these words, they will feel that.

Do you think he was able to fulfill his life mission?

KENNER: Oh, without a doubt. I think his goal of putting his team on the map and telling the story of his neighborhood -- the realities of the forces that shaped him into the man that he became -- I think that that story will live on. It's really up to the rest of us who care about him and listen to his music and feel his passion and his purpose to continue that work. And that's what it means to say "the marathon continues." It's about laying one brick every day to build a great pyramid. Although Nipsey Hussle did not live to see the whole pyramid completed, I think that his family and all those who love and respect him are gonna make sure that the work goes on.

I hope that the book can be part of that legacy being upheld. People will get a fuller sense of all the things he was about because he was definitely more than a rapper, definitely more than a businessman. He was trying to uplift his whole community, unite the streets of LA and bring these organizations back to their original purpose. He was a visionary ahead of his time.

The Marathon Don't Stop is out now via Simon & Schuster. Purchase it here.