- Virgin

- 2001

The song that eventually summed up Black Rebel Motorcycle Club was once an outlier. Three tracks into their debut album, it was called “What Ever Happened To My Rock ’N’ Roll (Punk Song).” While the parenthetical descriptor could maybe come across as a wink, the track itself was earnest — a snarling, charging track that teased out some personal me vs. you against the backdrop of being a true believer. As Peter Hayes sang in the chorus: “I fell in love with the sweet sensation/ I gave my heart to a simple chord/ I gave my soul to a new religion/ Whatever happened to you?/ Whatever happened to our rock’n’roll?"

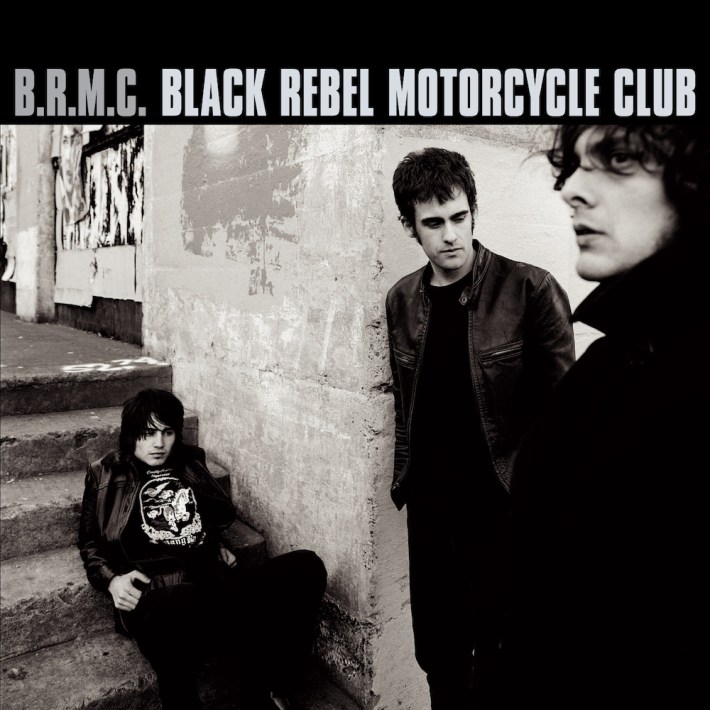

When B.R.M.C. arrived -- 20 years ago tomorrow -- the band was briefly seized upon as one of those would-be saviors of rock music. It’s the classic story: The genre was perceived to have withered or waned or grown perverse, and now a new generation would reinvigorate its original sense of danger and excitement. It’s not as if rock was only nu-metal by the end of the ‘90s. Hayes, for his part, had exited the Brian Jonestown Massacre, tying him to a certain stoned ‘90s indie side-story also involving the Dandy Warhols. When he linked up with his high school friend Robert Levon Been and drummer Nick Jago to form Black Rebel Motorcycle Club in late ‘90s San Francisco, they were just ahead of the big retro-rock boom. Something was in the air, but while the music press of the time would soon embrace the ascendant New York scene, BRMC were destined to be lost in history — a fate that, some would argue, was always where they were headed.

“Whatever Happened To My Rock ’N Roll” and its swaggering counterpart “Spread Your Love” were the big singles, the tracks that found their way into music video rotation and abundant sync opportunities. And it’s not as if BRMC didn’t fully exude a certain interpretation of rock’s bygone spirit. Leather-jacketed, brooding and removed onstage, with songs that often captured an adolescent angst or vaguely articulated rejection of society, they were a perfect manifestation of their name: A signifier of some wilder past, but not a completely literal pastiche. Nevertheless, aside from a dalliance with NME’s infamous pattern of effusive hype then betrayal, BRMC never quite endeared themselves to the “cool” corners of the pop history narrative. Within months, the Strokes released Is This It, and the entire landscape was altered. In comparison, it was easy to seize on something like “What Ever Happened To My Rock ’N’ Roll” and dismiss BRMC as the self-serious, lumbering archivists of this new generation.

Maybe this is just a sign of how different attitudes and perceptions were in that early ‘00s rock moment, but it now feels uncharitable that BRMC were sidelined as if they were some kind of howling blues-rockers. BRMC were drawing heavily on bands like the Jesus & Mary Chain and Ride, and they occasionally had tints of Spiritualized or Oasis. Maybe this, in some way, seemed uncool if you were in New York and felt a rawer form of new rock music bubbling up. But if you were, say, a kid listening to B.R.M.C. under perpetually grey skies in small-town Pennsylvania, the shadowy distortion and moody atmospherics of the album were not only evocative — they were a gateway drug to all kinds of psych-rock and bands that were ever so slightly more sonically adventurous than the touchstones that’d soon come to define the early ‘00s rock revival.

“Whatever Happened To My Rock ’N’ Roll” may have stood out as some kind of unintentional mission statement for B.R.M.C. and BRMC alike, but back then you could just as easily regard it as a tangent on an album that was rich with melancholy and distortion-as-shelter learned from shoegaze. Once you got past the semi-ubiquitous singles, you had the heartbreak pulse of opener “Love Burns,” you had the frayed drama of “Red Eyes And Tears.” “Awake” almost did the quiet-loud grunge dynamic, but smeared out of focus, its aqueous verses erupting in a chorus of swirling, gentle noise. “White Palms” and “Rifles” managed to be foreboding and infectious at once, while “Too Real” took BRMC’s Anglophile tendencies up to the present with its moving approximation of post-Britpop’s floating-above-the-rain-clouds reverie. While not all of BRMC’s themes were subtle, sometimes their aesthetic was. At the end of the album, they offered up “Salvation” in song and effect, crafting a casually gorgeous, flickering reflection — a song for in-between times, blue just-before-night twilight or creeping early morning hours, a moment of peace after the album’s darkness.

B.R.M.C. itself was generally well-received, and buzz still surrounded the band for a time. The backlash soon brewed. Amidst a rocky relationship with the press, BRMC were also at odds with a label the size of Virgin; in a Vice Rank Your Records feature, Hayes recalled the label looking for another “Rock ’N’ Roll” or “Spread Your Love” while the band was working on their 2003 sophomore album Take Them On, On Your Own. In 2005, they temporarily parted with Jago and pivoted to the Americana and Beat quotes of Howl, to some side-eyes and to some begrudging respect. But around that same point, BRMC’s story had been decided by those who already disliked them, they had forged a loyal fanbase that didn’t care one way or another, and they had begun to show that, really, they were always a band somewhat out of time.

It’s incredible to recall that one of the great criticisms of this band wasn’t just the fact they were exhuming a certain kind of rock styling, but that they were derivative of those aforementioned bands, the plain J&MC and Creation Records worship. Perhaps this is the benefit of hindsight, but the idea of a group being slammed for retro leanings in the 21st century is… laughable. In 2001, we were just getting started with retro trends. Through the ‘00s, some ‘90s alt-rock persisted, but beginning with NYC’s retro-rock boom and continuing on strong through the ‘10s, different cycles of retro revivalism have, in a sense, been the only “newness” in whole swathes of indie and rock and even pop music. In a lot of ways, BRMC got a raw deal. Yes, there was a shtick at play here. But could you really say that was all that much sillier in BRMC’s hands than, for example, a group like the White Stripes? There were all kinds of posturing and cosplay in the indie scene of the ‘00s. If you were young and exploring these bands, you could do worse than the heaving, immersive sounds of B.R.M.C..

As the decades passed, however, those who took “Whatever Happened To My Rock ’N’ Roll” as the band’s whole identity and ignored the weirder textures of their work otherwise turned out to be correct. Those weirder textures began to get ironed out by the time Hayes and Been reunited with Jago for 2008’s Baby 81, a slick album that foreshadowed the group sliding into a pattern. Even once Jago was finally out of the band and the Raveonettes’ Leah Shapiro replaced him, Hayes and Been settled into a groove: Each of their ‘10s albums had bits and pieces of what they do, but increasingly the rockers got more rote and soulless, the gloom flattened and lost its allure, and the spacier aspects of their sound got sanded down. There are still good BRMC songs to be found in their later years. But increasingly a snide question asked 20 years ago seems to have indeed become a guiding principle. Regardless of what happens around them in the music world, BRMC have stayed true to a compass — a compass that, unfortunately, has led them towards being the sort of snarling, chugging biker rock band their name always made them appear as.

Despite — or because of — their arc since, BRMC’s earlier work holds up better than one might’ve expected back then, better than a whole lot of other once-hyped ‘00s bands that have faded far further from memory. If you can separate B.R.M.C. from all the overbearing context of 2001, it stands as an outlier in its time the same way “Whatever Happened To My Rock ’N’ Roll” was once an outlier in BRMC’s story. A band from San Francisco, leather jackets and rock postures and all, made an album that was like a more direct shoegaze, an album of convincing turn-of-the-century Brit-indebted rock. Later on they would chase more banal iterations of that sound. But for a time in those early days, they were tapped into something more otherworldly. They were wondering what happened to their rock ’n’ roll, and stumbled into something just a bit more interesting. Two decades later, if you revisit B.R.M.C. and imagine a completely different route this band could’ve taken from here, it’s enough to leave you wondering why any of us spent the early ‘00s asking about rock ’n’ roll to begin with.