We’ve Got A File On You features interviews in which artists share the stories behind the extracurricular activities that dot their careers: acting gigs, guest appearances, random internet ephemera, etc.

By the time he was 18, Richard Thompson had already played in three bands -- including the seminal, beloved, and still-going folk-rock group Fairport Convention, which he joined when he was just 16 years old. By the time the British songwriting legend was 21, Fairport had released at least two indisputable classics -- What We Did On Our Holidays and Unhalfbricking, both in 1969 -- and survived a van crash that took the life of drummer Martin Lamble and Thompson’s girlfriend Jeannie Franklyn. Then, he left the band in 1971 to continue on with an impressively winding and prolific career, working with some of folk and British pop’s leading lights. He's still going strong today.

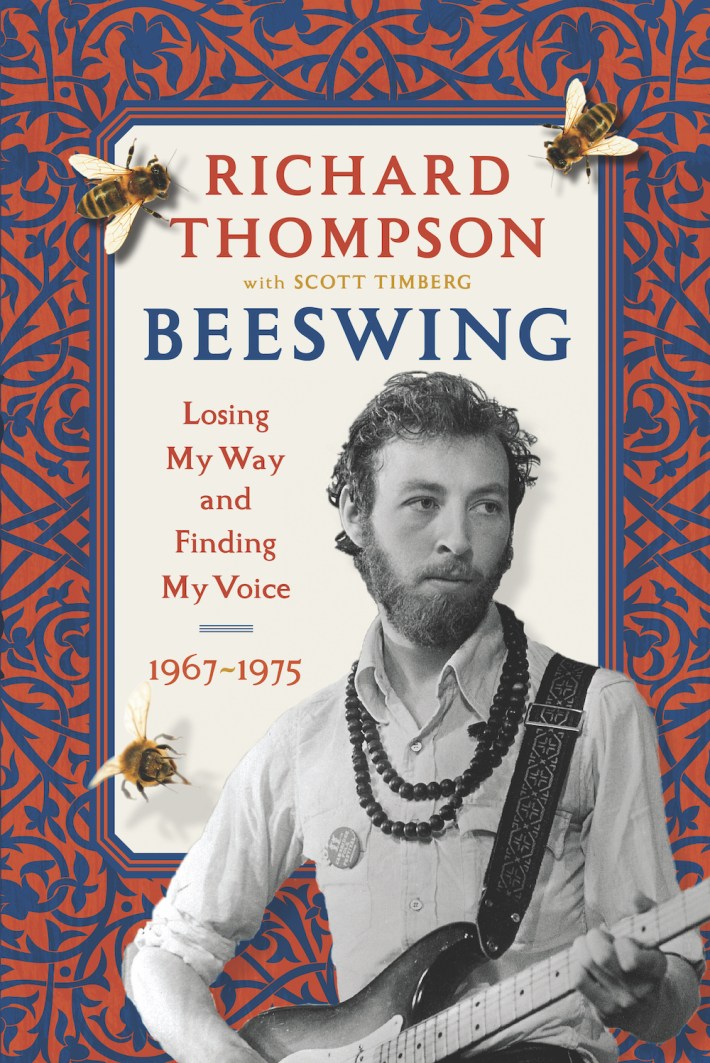

As suggested by the title, Thompson’s new memoir Beeswing: Losing My Way And Finding My Voice 1967-1975 zooms in on that early period in his storied musical journey -- through his early records with singer and then-wife Linda Thompson, including 1973’s canonical I Want To See The Bright Lights Tonight, right up to his brief hiatus from the music industry altogether. But there’s a lot to explore when it comes to his 50-year-plus career, to the point that during our hour-long phone conversation, Thompson found himself discovering that even the recent past sometimes felt like a distant memory.

It’s simply impossible to cover every nook and cranny of his intimidating CV, but the insights he provided throughout were reflective and revealing of someone who values hard work and efficiency as true virtues -- which might explain why he’s still thriving all these years later.

Emil And The Detectives (Mid-'60s)

This was one of your first bands in school -- you formed it with Hugh Cornwell of the Stranglers.

RICHARD THOMPSON: We were both in school, about 13 or 14 years old. I was in a band before that, believe it or not -- an instrumental group around the age of 11. Hugh bought a crude, homemade bass guitar off of another kid, and we had a drummer, so we had a trio going for a while. At some point, we got another drummer who was from the same school. We played what a lot of people in London were playing around that time -- R&B covers, blues, a lot of Chuck Berry and Bo Diddley. Not a particularly original repertoire. I drifted away from that when I fell away with Simon and Ashley in Fairport Convention, who I was playing with by the time I was 16. When I left school, I didn’t see Hugh again for about 40 years, which was bizarre. We met up again at a festival in Spain and it was like continuing the conversation we left off in 1967. [Laughs] We’ve been in touch ever since.

Sonically, you guys took such disparate paths after you stopped making music together.

THOMPSON: Absolutely. And with Fairport, we started recording very quickly and playing shows. As soon as we formed, we were working all the time. Hugh didn’t get going with the Stranglers until 10 years after that. He was a lot more assured and, hopefully, more sensible when he really hit his stride. We did a show together at the Royal Albert Hall about 16 months ago.

Session Work On Nick Drake’s Five Leaves Left (1969)

You played on Bryter Layter, too.

THOMPSON: Nick cut the track, I came in last with electric guitar. I did that on both records. We recorded at Nick’s studio, where we did all the Fairport stuff too. The electric guitar on the track was spliced from two or three different takes.

What were your memories of Nick?

THOMPSON: I saw him a lot because we had the same management company and record label. It was a time when a lot of people were taciturn, to say the least. You might put that down to drug culture, people just being introverted. So Nick didn’t seem unusual in that way. I knew other people who were withdrawn, and I was very shy as well, so it’s not like I was clapping Nick on the back and saying, “How you doing, mate?” In my book, I mention one meaningful conversation I had with Nick, and that was about it. It was lots of nods and smiles and not much else.

Did you record your work on that record before or after Fairport Convention’s van crash?

THOMPSON: Before.

That was obviously a very intense time for you.

THOMPSON: It was difficult. It was a time that we looked at each other and wondered if we wanted to continue being musicians. Ultimately, we thought that we should carry on in memory of our drummer who was killed. We probably also thought we weren’t very good at anything else, so we should persevere. But it was up in the air for a while.

Henry The Human Fly (1972)

This record marks one of a few instances in your career where you put out a record that wasn’t well-received at first but took on a second life later. But to have your first solo album be poorly received must have been tough.

THOMPSON: I thought it was in some ways a good record. I knew there were some things I didn’t like about it, even after it was put out. I didn’t sing well enough on it, and the songs were quirky and quite personal in some cases. I wasn’t sure that would get across to other people, and I certainly didn’t think it would sell a whole bunch of copies. So the reviews were, really, pretty bad in the UK. It didn’t kill me, but I thought, “Well, I won’t be making another solo record for a while, and I’ll move on.” When it was released, I was starting to do shows with Linda, and I thought, “Well, she’s a stronger singer than I am, so we can work as a duo and perhaps that’ll play to our strengths much more.” We started working on the Bright Lights record, which I think is a good record and holds up very well.

There’s nice and interesting things about Henry The Human Fly, but it’s a weird record. I see people say, “That’s my favorite record of all time,” and I say, “What? Are you out of your mind? Are you insane?” But there are people who have taken that record to heart, and I’m very shocked by that, especially when they disregard everything else I’ve done to choose that one. But that’s people for you.

How important has critical opinion been to you throughout your career?

THOMPSON: [Laughs] It’s hard to ignore the music press. Even back then, you had to pay attention. Also, you knew most of the journalists from being at shows and doing interviews, so if they slammed your record, you knew who they were, which was a bit more personal and upsetting. With any kind of criticism, you take it as something outside of you. It’s good and bad, and praise is sometimes as distorted as negative criticism is. You build up your own sense of worth and you think, “Well, I know this is good on my own terms, people are praising it far too much or too little, that’s not really real, so I’ll stick to my own view of my own work.”

When you get to be as old as me, you’ve seen it all, and at some point people pigeonhole you and decide who you are. Whatever you do, you’ll never shake it, so you have to put up with it. You can make what you think is an amazing record, and people will say, “More of the same,” and you’ll say, “What? Are you crazy?” More and more you have to rely on your own sense of worth and hope that that steers you.

John Martyn's Solid Air (1973)

THOMPSON: It was always fun working with John. I’m pretty sure we did everything live. John was fairly tight with money, so he wanted to get stuff down as cheaply as possible. [Laughs] He was someone who could play live -- a good guitar player, and a good singer. He could put it down, and the sessions were over fairly quickly for all those reasons.

Later in his life, he had issues with substance abuse and domestic abuse allegations. What was your level of familiarity with him during that time?

THOMPSON: Not very familiar at all. After the ‘70s, I really didn’t see John hardly at all. He was becoming difficult. When I knew him in the ‘60s, he was a really sweet human being. We were neighbors for a while, I used to go over his house and we’d play records and hang out, which was great. The ‘70s, whatever he was doing -- I suppose drinking, mostly -- was getting to be something that made me want to keep further away from him.

I didn’t see him much in the ‘80s and ‘90s. I ran into him at a couple of festivals. It was nice to see him, but I was disturbed to see the state he was in. The last 20 years of his life, I did not see him very much, which was a shame. But he was someone I couldn’t be around. He moved to Ireland, too, which meant I didn’t run into him on a regular basis. I’d hear from Danny Thompson, who did keep in touch with him, about how he was doing -- and the reports from Danny were upsetting. I was very sad when he passed away.

I Wanna See The Bright Lights Tonight (1974)

How do you perceive the legacy of this album?

THOMPSON: I don’t think in terms of albums -- I think in terms of songs. Some songs, from any decade in my career, I still sing. There’s still half a dozen songs from that record I sing with regularity, so there must be some songs with staying power there. In terms of the album, it was a lucky one. It came together really well, we recorded it in about three days, it cost 2500 pounds to record, which was unbelievably cheap. It still sounds good today sonically. We had a great engineer, John Wood, working on those records, and he gave the sound a timeless quality. There’s no trendy compression or flanging happening on it. Sometimes things just work.

John Cale’s Fear (1974)

THOMPSON: I knew John from various sessions with various people. I forget how many guitar players he wanted on the track -- maybe four or five, all playing the same thing. I think Mick Ronson was on there, and Phil Manzanera. I haven’t actually heard it since I did it, so I’m vague on how it sounds. But it was fun. A half an hour of work, it didn’t take very long.

Sandy Denny’s Rendezvous (1977)

THOMPSON: I played on that, did I?

It says you did!

THOMPSON: Probably on one track, certainly not on the whole record.

The “Candle In The Wind” cover.

THOMPSON: Right. In ‘77, Sandy still seemed in reasonable shape to me. The session was fine, she seemed fine. I can’t remember the actual process of recording at all.

Do you remember the last time you spoke to her before she died?

THOMPSON: Not really. It was sporadically. She moved to the country. She was someone I’d see a lot when she lived in London in the early ‘70s. I saw her less often after that. Then I moved to a different part of the country as well. I probably spoke to her on the phone more than I saw her. When she had Georgia, she phoned Linda every day with baby questions.

It became clear that she wasn’t cut out to be a mother. She had the love of a mother, and the hormonal urge, but she wasn’t very good at the actual process of looking after a baby. She was still doing drugs and drinking and God knows what. It was very irresponsible and selfish, really. Increasingly, Sandy had a hard time dealing with the world, and she chose to numb it with drink and drugs. It was alarming to hear that Trevor had taken Georgia to Australia to be raised by his parents. That was probably going to be too much for Sandy. That wasn’t the reason she died -- she died by accident, probably not deliberately -- but it was hard to hear, and a tragic story. I still think about Sandy all the time, and I miss her.

Playing On Julie Covington’s Self-Titled Album (1978)

https://youtube.com/watch?v=5OCyrS2gM_w

THOMPSON: Julie was great. She was such a nice person -- different from most of the singers you’d work with, I think, because she was an actress. She was very down to earth and unpretentious. The sessions were with a high-powered American rhythm section, and we put the tracks down fairly quickly together. It was recorded at Brittania Row, Pink Floyd’s studios, and we piggybacked off of that album and borrowed the rhythm section to work on First Light with Linda. I even got to be in a video with Julie, which was quite fun.

Gerry Rafferty’s Night Owl (1980)

You guys had a falling out.

THOMPSON: [Laughs] Where do I start? I knew Gerry a bit. Linda knew him better, because they both grew up in Glasgow and were in the folk scene there. I don’t remember much about playing on Night Owl, but Gerry approached us and said, “I’d like to produce a record with you guys.” He had such a huge success with “Baker Street” that we thought that was a good idea, and that perhaps some of his magic would rub off on us. We recorded the record, and I got fairly uncomfortable with the recording process, because it was dense -- everything was triple-tracked. Everything sounded very squashed, there wasn’t any air left in the music.

When the record was mixed, I listened to it and said, “I really don’t want this released, I’m sorry. I don’t like the way it sounds.” So it wasn’t released. Then we were approached by Darrell Boyd who was like, “I know you did this record and you’re not releasing it, so let’s re-cut it and I’ll put it out on my label. We can do it cheaply and we can spend the money we save on the US tour.” That seemed like a good option for us.

Jake Thackray And Songs Appearance (1981)

THOMPSON: Jake was an interesting guy. He was in the folk scene, which was a very distinct thing -- it’s not part of popular culture. Even him having a TV show seemed exceptional, probably because he came off more as a nightclub entertainer. He was more in the school of Noël Coward or W.S. Gilbert, with clever wordplay. That got him some measure of popular appeal. But he was also very eccentric in his delivery and musical persona. Linda and I did the show, and it was filmed in a little theater that was laid out with tables and people sitting around. Had to be an audience of 50 people.

“Shoot Out The Lights” (1982)

You mentioned thinking more about songs than albums. Tell me about this one.

THOMPSON: It started with a riff, really. I always thought it sounds like Dwayne Eddy. My sister used to have a record of his called “Ring Of Fire,” which was a whole different song than the Johnny Cash song. It was a really slow riff, and I always really liked it. I was trying to do something inspired by that, really -- and from the riff comes the idea of the song.

What I was thinking about at the time was the Russians in Afghanistan. I was upset about what they were doing to the Afghanis -- almost as bad as what the Americans did a little bit later. [Laughs] The Russian helicopters are coming in and mowing down these noble warriors and villagers. A friend of mine was in a film crew in Afghanistan, and he was in a village that got attacked -- he suffered some shrapnel wounds at the time. I was thinking of this urban description of a killer, but it’s really a metaphor for the Russians.

Contributing “How Many Times” To Fairport Convention’s Gladys' Leap (1985)

THOMPSON: That was a song I’d already had and been playing in solo shows. Fairport really just did a cover of it. At some point, they stopped playing in the ‘70s, and after a few years they had a reunion festival, which I took part in either the first or second -- and then it became a regular thing as the Cropredy Festival, which I play every few years because it’s nice to play with the old band. It’s nice to see such a great audience that loves folk music, too. Such a pleasure to play there.

Touring With David Byrne (1992)

THOMPSON: We did a couple of co-bills, including one at St. Ann’s Church And Arts Center in Brooklyn. We did individual sets and we jammed on a few things. I’m a great admirer of David -- one of the more interesting and thoughtful people in popular music. I’m always interested in what he’s doing, he always has such great ideas. Plus, he has a very strong visual artistic sense that adds to the fascination of him as an artist. He’s someone who never stops moving and exploring musical possibilities.

Performing On Late Night With Conan O’Brien (1994)

You played Conan’s show twice. What’s the difference between appearing on American TV vs. the BBC?

THOMPSON: American talk shows are very organized -- they’re doing this stuff five days a week with different music every night. It’s very professional, and Conan is no exception to that. I can’t remember the first time I was on his show, but I remember the second time. Conan’s a guitar player, and he loves to take an interest in guitar-playing guests -- he brings out vintage Fender guitars and stuff. [Laughs] He seems like a really nice, genuine human being.

“Dear Mary” With Linda Thompson (2002)

This is the first time you were on record with Linda since Shoot Out The Lights.

THOMPSON: It’s funny -- Linda and I have been friendly for the last 15 or 20 years. It was nice for her to ask me to play on something, and I was very happy to make the gesture of doing it. I can’t remember the actual session. [Laughs] She’s had some progressive dysphonia in terms of her singing and needs some help in the studio to get the notes out these days, and she’s had some good help too.

The Old Kit Bag (2003)

This was your first self-financed record. How did that reflect your experience with the industry at large at that point?

THOMPSON: I got dropped by Capitol/EMI, and it was probably time anyway. It was a strange time in the music business, really. A lot of people were saying, “What’s the point of a major label? We never see any money.” There were various accusations across the music business of creative accounting -- however much you earn, you’re not going to profit, which is a similar accusation made of film companies. The record business was going that way, and there were great things about the major label system, but bad things, too. By the early 2000s, a lot of people were migrating away from majors to a cottage-industry model where it was easier to see that record sales were this much, so you were gonna get paid this much. It was a new thing for me, as well as other artists.

So the small-label model -- well, I suppose I’m still there 20 years later, where things are more transparent and we don’t spend as much making records as we used to. That could be a good or bad thing, but generally it’s a good thing. And if you have a successful record, then it’s easier to see how things break down. Also, promotion has changed so much in the last 20 years. Big record labels used to do everything in-house. I think most people these days prefer a grassroots approach. You can promote so much more on the internet. It’s easier to get your stuff out there in that sense.

The whole model of the music business has changed, and it will probably change some more. At some point, the whole streaming idea will have to change, because it’s not sustainable for musicians and writers. I’m expecting that in the next five years that’s gonna become much more musician-and-writer-friendly, somehow.

Scoring Werner Herzog's Grizzly Man (2005)

THOMPSON: I was a big Werner fan. I’d seen a lot of his films, and I thought he was a visionary filmmaker, so I was thrilled to be asked to work on Grizzly Man. It was decided early on that it would be an improvised score, so we gathered musicians who were good at improvising at San Francisco’s Fantasy Studios -- which is sadly not there anymore, I think it’s a car park or something. Ridiculous. There’s not a lot of music in his films, it’s more like a wash of background, so we were aware that each musical cue had to have some power, logic, and integrity. It went fairly quickly. We did the whole thing in two days, and we had enough material left over for the spin-off TV series. At the beginning of the process, he liked to be out there on the floor with the musicians, but at a certain point he grew to trust enough that he knew he was better off in the control room.

Making Still With Jeff Tweedy (2015)

THOMPSON: I can’t remember who approached who. I think we asked Jeff if he’d produce something. He did a great record with Mavis Staples, and I thought, “If he can do that, perhaps he can do something with me.” So my rhythm section went to Chicago, and it was January -- it was freezing. My God, it was cold. [Laughs] We went to the Wilco studio, which is in a loft space. They have two floors. The lower floor just holds their touring gear, and the upper floor holds instruments. Hundreds of guitars, basses, keyboards, amps, everything. Fascinating place. A cave of goodies if you’re a musician.

Jeff’s greatest virtue is knowing what a song needs. “Do you really need that other verse? Let’s add something there.” Having some feel of the arc of a song and knowing what kind of sound would enhance it. It was a very relaxed and laid-back process, and we didn’t have any major issues with sound. We did the whole thing in ten days because of our schedules. But it was cold. [Laughs] Driving from the city center out to the studio every day, we were taking our lives into our hands. The roads were like glass, they were so hazardous. But we got there and back.