February 20, 1988

- STAYED AT #1:1 Week

In The Number Ones, I'm reviewing every single #1 single in the history of the Billboard Hot 100, starting with the chart's beginning, in 1958, and working my way up into the present.

Historically, the world has never been an easy place for the singers of dance-pop songs. Dance music is, for the most part, a producer's genre. The producers make the beats, write the songs, and hire the singers. But those producers aren't the people who connect with audiences, who communicate the passion and hunger and heartbreak of those songs. For that, they need singers. Every once in a while, those singers will rise to stardom, and they will find their way into people's hearts and memories. Most of the time, though, those singers are considered expendable. They're easily discarded, swapped out for other singers. They're paid next to nothing. They are the stars of these songs, and yet they are not the stars at all. It's a strange arrangement.

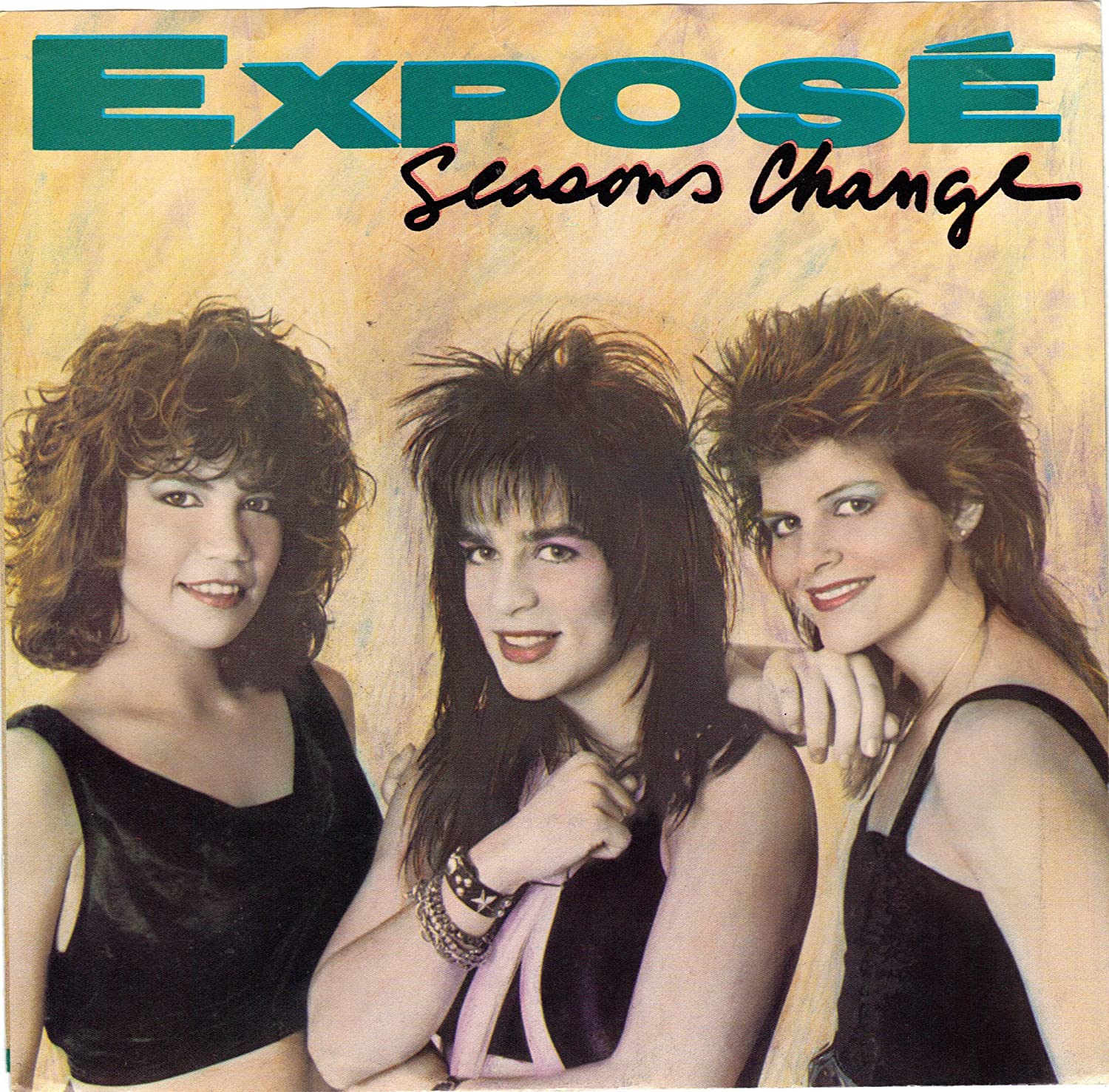

Exposé, the Miami trio who became some of the biggest stars of the late-'80s Latin freestyle boom, were basically the exception to the plight of the dance-pop singer. Exposé's 1987 debut album Exposure sold millions, and all four of its singles reached the top 10. When Exposé finally reached #1, they did it with "Seasons Change" -- a ballad, not a dance song at all. Even after that triumphant moment, Exposé kept making hits for years, into the early '90s. They had legs.

In some other important ways, though, Exposé's whole story illustrates the plight of the dance-pop singer perfectly. The group was formed and controlled by their producer and songwriter, and they had no job security. Even at their peak, the members of Exposé were stuck in strict contracts, reportedly only paid a few hundred dollars per show. They knew they could be replaced at any moment, since they were already replacements. They were the second version of Exposé.

Exposé was the project of Lewis A. Martinée, a Cuban-born DJ and producer in Miami. Martinée hung out in Miami discos in the late '70s, and he started making music himself in the early '80s. Under the name Techno Lust, Martinée released a synthy dance single called "Woman" in 1983, and he and a couple of friends started up a label called Pantera to release it. Martinée figured that "Point Of No Return," another track he wrote, would sound good with a girl singing it, and he liked the way his girlfriend Alé Lorenzo sounded when she sang along with songs on the radio, so he recorded her singing it. Martinée formed a group around Lorenzo, adding two more singers, and he called it X-Posed. In 1984, X-Posed released "Point Of No Return" as a 12" single on Pantera.

"Point Of No Return" is an absolutely bulletproof club banger. The song came out just as Latin freestyle was coming into its own, and you can hear that freshness and immediacy in the track. There's a lot going on in "Point Of No Return" -- blippy and staccato early-electro synth stuff, simplistic disco vocals, Afro-Latin percussion, proto-house pianos, even a screaming guitar solo -- and it combines them into one dizzy and passionate blur. After X-Posed changed their name to Exposé, "Point Of No Return" became a #1 hit on the Billboard dance charts, and that success, as well as the success of second single "Exposed To Love," got Exposé a contract with Arista. (Neither single crossed over to the Hot 100.)

But while Exposé were working on their debut album, Martinée got rid of all three members and brought in a whole new group of singers. In the Los Angeles Times, Dennis Hunt wrote that Arista demanded the lineup change: "The word was that those women had the wrong look and little star potential." (That same article claims that Clive Davis, the executive in charge of Arista, wasn't interested in Exposé even after the complete overhaul of their lineup: "Davis is simply skeptical about signing dance acts to album contracts because they have no longevity." You could say that Hunt's article, with its anonymous-source quotes, was an exposé on Exposé.) Meanwhile, Martinée claims that he decided to replace the group and that Arista had nothing to do with it. Other accounts have claimed that the members of Exposé all wanted to leave and that they made the decision on their own. Supposedly, Alé Lorenzo picked her own replacement. Any way you tell the story, there's clear record-label shadiness at work.

The second version of Exposé began in 1986, when the original members were already working on their debut album. (All three of them had vocals on the album. None of them were credited.) LA native Jeanette Jurado sang for an R&B cover act that opened for the original version of Exposé in California, and Martinée brought her in as the new lead singer. (When Jurado was born, the #1 song in America was the Rolling Stones' "Get Off Of My Cloud.") Martinée also hired Gioia Bruno, an Italian-born singer who'd been raised in New Jersey, and Ann Curless, a recent University Of Miami grad. This became the new Exposé.

Club audiences weren't into the idea of a whole group being fired and replaced, and the new version of Exposé got booed and heckled at some early shows. But that new Exposé quickly notched a big hit of their own. "Come Go With Me," the first single from the new lineup, topped the dance charts and then crossed over, reaching #5 on the Hot 100. (It's an 8.) Suddenly, Clive Davis got interested, and he suggested that the new lineup record a new version of "Point Of No Return." They did, and that one became a hit, too, also peaking at #5. (It's a 9.)

Lewis A. Martinée wrote and produced every track on Exposure, Exposé's debut album, and the LP is a monster, a consistently enjoyable burst of bubbly percussion and pop hooks that barely ever lets up. Latin freestyle was always a singles genre, but almost every track on Exposure sounded like a single. Plenty of those tracks did become singles. A third hit, the relatively smoky midtempo jam "Let Me Be The One," also reached the top 10, peaking at #7. (It's an 8.) There are only two tracks on Exposure that aren't really dance songs, and after all those hits, Exposé finally released one of them as a single. Against odds, that song became their biggest hit and their only #1.

"Seasons Change" sounds like a song written for a Miami Vice montage. Maybe it's Don Johnson in his sunglasses staring out at a glittery ocean as the sun sets. Maybe he's thinking about a woman who broke up with him an episode or two ago. Maybe the show is dissolving into scenes of the two of them together, hugging and laughing. It's that kind of song -- a wistful ballad that sounds like it was written as a for-hire job.

Martinée has said that he wrote "Seasons Change" after he turned 30 and got all reflective about it. The lyrics are bad middle-school poetry: "Some dreams are in the night time, and some seem like yesterday/ But leaves turn brown and fade/ Ships sail away." Jeanette Jurado has an appealingly raw and sentimental R&B delivery, and she keens about the merciless march of time and the things we leave behind: "I'd sacrifice tomorrow just to have you here today." Smooth-jazz saxophonist Steve Grove wails away gloopily. It's pure sentimental '80s cheese, and not in an unpleasant way.

When a group like Exposé makes a bunch of exciting dance records but then hits big with one sleepy ballad, I tend to get vaguely irritated: This is the smash? In a lot of ways, "Seasons Change" is generic adult-contemporary fluff. But it's generic adult-contemporary fluff as rendered by a dance producer, and there's something interesting about that. The song has restless synth-bass bloops and oscillating keyboard lines, just like a dance song, presumably because that's what Martinée knew. I like the whole wistful-synthpop aesthetic a lot better than the somnambulant orchestral churn that Exposé's Arista labelmate Whitney Houston was using on her own ballads around the same time. Compared to its competition, "Seasons Change" sounds smaller and somehow more personal.

"Seasons Change" is an absolutely dated song; those keyboard sounds and sax eruptions tie it firmly to an isolated moment in pop history. But the production improves the song, too. The central hook of "Seasons Change" is pretty weak, and I can never remember it when I'm not actively listening to the song. But there are other hooks on "Seasons Change," just in the little ways that those keyboard riffs interlock. The song seems like it wants to be boring, but it can never quite get there. It's too unpolished, and it wants to dance too much.

"Seasons Change" also gains something from the presence of Jeanette Jurado. After Lisa Lisa And Cult Jam, "Seasons Change" made Exposé the second Latin freestyle group to reach #1 with a single that wasn't really Latin freestyle. Like Lisa Velez, Jurado has a big, commanding voice that pairs nicely with an almost-untrained innocence. She can clearly belt, but she also sounds young and green, and that rawness works for the song. She can access the ache in a way that doesn't feel overstated. Also, I really like the drawn-out wordless note that she hits at the end of the track.

"Seasons Change" hit #1 almost exactly a year after Exposure came out, and it represented a crowning achievement for an unlikely smash of an album. Exposure went quadruple platinum, and Exposé quickly got to work on their sophomore album What You Don't Know. Lewis A. Martinée wrote and produced that whole LP, too. The album came out in 1989, and while it only went gold, it also shot three more singles into the top 10. ("What You Don't Know," the highest-charting of those singles, peaked at #8. It's a 6.) With the album's success, Exposé became the first girl group since the Supremes to land seven consecutive top-10 singles.

While touring behind What You Don't Know, Gioia Bruno developed a vocal-chord tumor, and she lost her voice, becoming unable to sing for a few years. Exposé replaced her with the excellently named Kelly Moneymaker. For Exposé's 1992 self-titled album, Clive Davis took over as executive producer and steered the group away from dance-pop and toward adult-contempo balladry; Martinée only produced a couple of tracks. (Martinée had gone on to other things, working with other freestyle groups and with mainstream pop artists like Debbie Gibson and the Pet Shop Boys. The Pet Shop Boys' Martinée-produced, freestyle-adjacent 1986 single "Domino Dancing" peaked at #18 on the Hot 100.) Exposé eventually went gold, and the Diane Warren-written ballad "I'll Never Get Over You Getting Over Me" reached #8. (It's a 4.) But Exposé didn't chart well, and Arista dropped the group in 1995. The next year, Exposé broke up. The singers were all apparently very happy to get out of their shitty contracts.

The original lineup of Exposé got back together in 2006, mostly playing Latin freestyle nostalgia shows and gay pride events. Kelly Moneymaker would rejoin the group when one of them couldn't make it to one of the shows. In 2007, the original owners of Pantera Records, not including Lewis A. Martinée, sued Exposé, claiming that they owned the rights to the group's name. Four years later, the actual members of Exposé won the lawsuit. A court found that the singers in the group "owned the goodwill" associated with the Exposé name. For once, a group of dance-pop singers won something. That should happen more often.

GRADE: 5/10

BONUS BEATS: "Seasons Change" is one of those #1 hits that disappears completely once it's no longer a #1 hit. The song is apparently on the soundtrack of the 1998 Meryl Streep movie One True Thing, for instance, but I can't find video of that online, and there aren't any prominent covers or samples of "Seasons Change." So instead, let's go with a different Exposé joint. On Pharrell's shockingly great 2016 mixtape In My Mind, there's a track called "Come Go Wit Me" where Pharrell and Clipse rap over the beat from Raekwon's "Incarcerated Scarfaces" and where Pharrell sings a bit of "Come Go With Me." Here's that song:

("Incarcerated Scarfaces" peaked at #37. Clipse's highest-charting single, 2002's "When The Last Time," peaked at #19. Pharrell will eventually appear in this column.)

THE NUMBER TWOS: The Pet Shop Boys and comeback kid Dusty Springfield's soulfully deadpan synthpop banger "What Have I Done To Deserve This" peaked at #2 behind "Seasons Change." I bought it drinks. I bought it flowers. I read its book and talked for hours. It's a 10.

Pet shop boys are a really underrated group.I love them !! My mom always used to listen to them.

— Cardi B (@iamcardib) March 22, 2021