The Canadian pop-punk band's singer recalls the making of his signature hit, a genre hybrid that stands as a microcosm of its pre-9/11 moment.

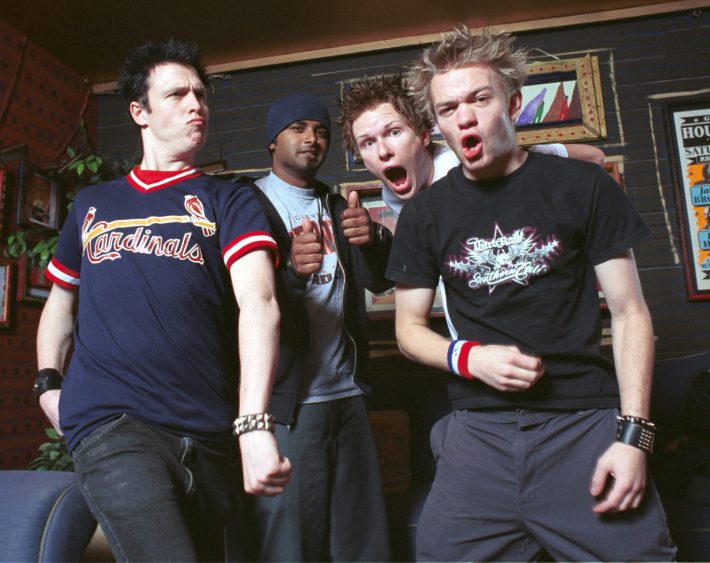

Deryck Whibley knew Sum 41 would be famous. It was always plan A. (Plan B was a career in the NBA). That idea of going to college and getting a “normal” job that his parents tried to sell him on seemed pointless.

A waste of time.

The band was going to make it. That was the only option. His bandmates' parents gave them all two years to do it. If that didn't work out, it was back to normal life.

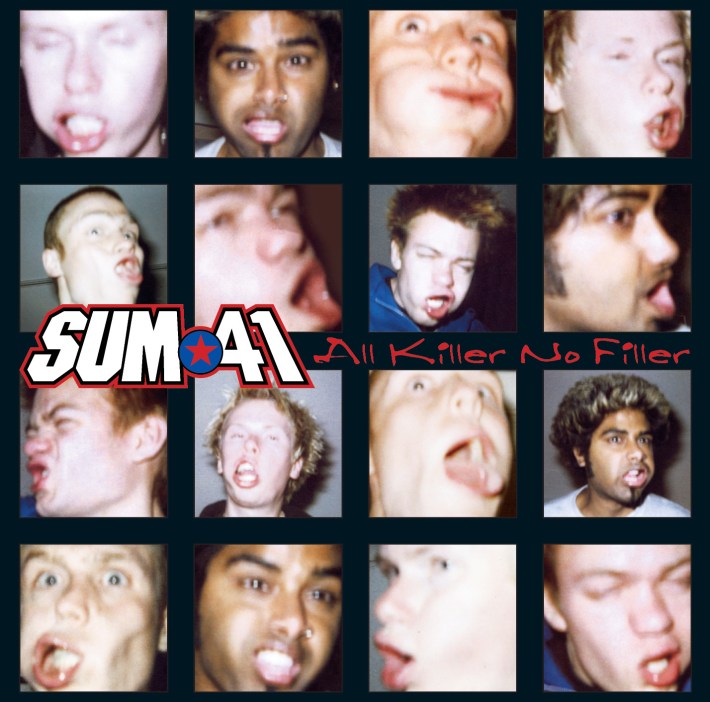

The bet on themselves paid off. Sum 41 launched themselves out of suburban Ontario and into pop punk stardom on the back of their major label debut album, All Killer No Filler, with time still left on their parents’ clock.

Lead single "Fat Lip," the song that introduced the band to the masses, was released 20 years ago today. It almost didn’t even get recorded for the album. "It was the last song I had written for All Killer," Whibley says, calling from his home in California. "The whole album was pretty much done. It was never meant to be a single. It wasn’t even supposed to be a song."

"Fat Lip" was everywhere. No matter what social subset or clique someone felt like they were a part of in 2001, this song was present. It was on MTV, SNL, video game soundtracks, movie soundtracks, mainstream radio. It was just rap enough, just metal enough, and just pop-punk enough to sound familiar but exciting, without any of those genres overstaying their welcome. It was all things at once. It was the genre’s past and its future. It just worked.

At a moment when those genres are once again colliding, the song is arguably as relevant today as it was then. That's a miraculous feat for an artist: to capture so many different components of one very particular time without that piece turning into some antiquated time capsule or cringe-inducing, irony-laden guilty pleasure fully relegated to emo night playlists. Aging gracefully isn't easy. Go back and listen to some other popular songs from that year.

It's also no easy feat to name your first real album All Killer No Filler and actually back it up. It might've been a joke at first, but it’s one of the most consistent pop punk albums of the era. "Fat Lip" wasn’t the only star-maker on the album; "In Too Deep," released as a single in September of that year, is evocative of that period of time just as much as "Fat Lip" is, earning spots on movie and video game soundtracks, too, and relevance beyond just nostalgia 20 years later.

All Killer No Filler was just over a half hour of near unrelenting pop-punk energy. The songs rarely went over three minutes in song length, and each one got to the point quickly, never taking the scenic route to a chorus hook. And what really made Sum 41 stand out amongst its competition and peers is the abundance of guitar solos. There’s no denying that the group owed a lot to the likes of Green Day and Blink-182, but guitar solos were something that neither of those bands ever really touched, at least not on the level that Sum 41 guitarist Dave Baksh did. The closest parallel was fellow metalhead kid Rivers Cuomo finding space for his KISS devotion on geeky songs about unrequited love. This was a pop-punk band that unapologetically shredded between choruses about youthful apathy, challenging authority and failed relationships.

But the world might not have noticed all that if not for the genre sampler that was "Fat Lip." The finished product as we know it is sort of an amalgamation of ideas, different song pieces that Whibley glued together over time. With so many sounds and textures and directions -- rap, rock, a pretty bridge giving way to a bombastic finale -- it was a lot for the band to assemble, and it couldn’t be right until it was 100% right.

"The very, very first thing I wrote was the guitar riff," he says. "And I didn’t necessarily write it for this idea that I had for this sort of punk rock-rap kind of thing. I knew I had this old school rap idea mixed with punk rock sort of stuff, but I wrote this riff just as a riff. And then I ended up writing a chorus, like, months later. And then I had this verse. And none of them were supposed to be together. They were just separate things that I was writing over time. And then one day it kind of clicked, and I thought, 'Well, these all kind of work. They’re all around the same tempo, they’re all the same key.' I changed a few things and made it work, now all of a sudden I was like, 'OK, I’ve got the rap part, I’ve got a riff, and I’ve got a chorus.' But I don’t have the rest of the song. And then it took a long time before pieces just kind of came together."

The vision of "Fat Lip" was always there in Whibley's head. Some of the directions were just a little fuzzy. And that’s what made it so difficult to get to its final form. The painting was visualized, he just had to get his hands and paintbrush to cooperate completely. Once he taped together a rough sketch of it, where it was somewhere close to what he was imagining, he took it to All Killer producer Jerry Finn with no idea how he'd react.

"I was really embarrassed, cause it had this old-school rap thing, and it just seemed kind of quirky and weird,” Whibley says. "I remember I played it for a few people, friends, and I don’t even think half the band really liked it. And it wasn't really like it was this great song that everyone loved. It was kind of like, 'Meh, it's kind of stupid sounding. And are you really gonna rap over it?' It was a bad demo. I played it for Jerry Finn, and he was like, 'That’s your first single. That's gonna be a hit.'"

Sum 41 never had a hit before. They had no idea what a “hit” felt like when they were writing it. They had an initial EP that bought them some attention from Island/Def Jam, and that was about as far as they got in terms of planning their careers at the time. But Whibley knew "Fat Lip" was special, possibly because of just how idiosyncratic it was within the context of their debut LP.

The high from Finn’s reassurance was short-lived, because now came the part where four guys had to make an ambitious idea make sense. And with an idea like this, there was a razor-thin margin of error between badass and corny.

“We went in and we recorded it a couple more times as a demo, and it just never quite felt right,” he says. “It took a year and a half to write, but then it took, like, I’m gonna say six months probably to record it over and over again to figure out how it should sound. And it just never came together. And the thing that really, finally made it come together, after all the writing was done, it was the rap stuff. And it was a simple fix. I just kept listening to it over and over and over again. We had it fully mixed and done and everything. Everyone else thought it was fine, and I just kept saying, ‘It’s not done.’”

The difference was one beat. It was there the whole time in the negative space.

“So, for example, it used to go, ‘Stormin’ through the party like my name was El Niño/ Hangin’ out drinkin’ in the back of an El Camino,’” Whibley sort-of sings over the phone, never totally committing, to my disappointment. “Once I realized what was wrong with it, it became “Stormin’ through the party like my name was El Niño / When I’m hangin’ out drinkin’ -- when you have that little thing to pull you into the next line is what made it all flow. Every line had to have that, all of a sudden we realized. When you listen to it, every line there’s a pickup word that takes you into the next line. They overlap each other. And that’s what made it all of a sudden a special song to me."

"Fat Lip" was released on April 22, 2001, just a little over two weeks before All Killer No Filler. America in April 2001 was perfect for something like this to resonate. Pre-9/11 naiveté gave the youth more license not to take things too seriously in life.

The rap-rock and nu metal revolution had been going strong for a while, with bands like Limp Bizkit, KoRn, and Linkin Park pioneering a new direction and aesthetic for American youth culture. Simultaneously, Green Day and Blink 182, arguably the two biggest names in American pop punk of all time, were at transitional periods of their careers, with Green Day exploring their folkier side on "Warning" and Blink about to release their more "serious" Take Off Your Pants And Jacket. Slacker culture was at its zenith, and the kids were as destructive as ever, as the new television phenomenon Jackass was captivating bored, impressionable suburban kids with access to mini DV camcorders.

Sum 41 was Island/Def Jam’s answer to a hole in the market. Kids who were too young for Dookie when it came out were now adolescent and looking for something of their own, preferably if it accompanied a skateboarding video or gross-out high school shock-comedy flick starring Seann William Scott. Even better if the song’s pivotal line is "The doctor said my mom should've had an abortion." Mothers grasped for their pearls and kids decided it was the gnarliest thing they’d ever heard.

A band made up of four teenagers who sent their demos to Island/Def Jam in the form of a video of themselves driving around Ajax, Ontario, dousing people with SuperSoakers, was just the band to fill that gap in the market. And a song about getting into trouble with your friends, laughing when old people fall, apathy, knowing you’re destined for bigger things, and flipping a middle finger to everyone who doubts you, is the perfect thesis statement.

In a 2001 Rolling Stone profile, the band said that the president of the label told them they could go out and destroy as much as they wanted. The record label would happily foot the bill, as long as they filmed it. “He said, ‘Go out and destroy the world. Just make sure you get it on tape,’” Whibley confirms today.

They did, and Whibley has actually been spending most of his time during the pandemic painstakingly cataloging years of footage, discussing what to do with it. (That is, when he’s not doting on his son, born last March.) "It surprises me sometimes, because I'm like, 'How was I so responsible by being so irresponsible all the time?'" he says. "I have no idea how somehow I was able to keep certain things."

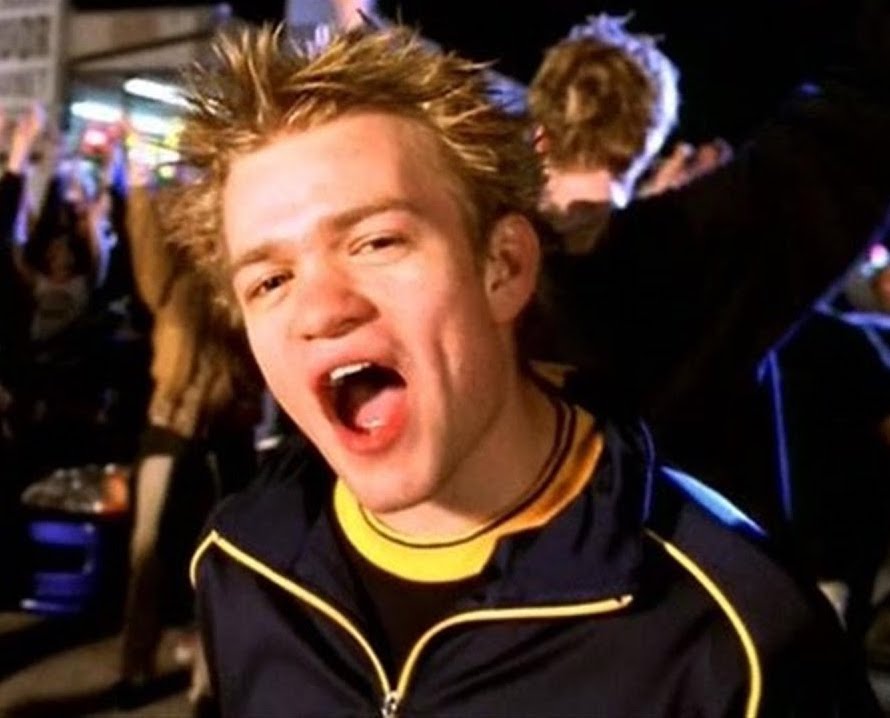

That record label money was also able to fund a real music video, which perfectly encapsulated the average suburban North American teenager at the time -- loitering en masse in a convenience store parking lot, sitting in a beat-up van next to a skatepark, and borrowed comedy tropes from American Pie and every movie like it. It cold-opened with Whibley, Baksh, and drummer Steve Jocz rapping for a convenience store employee, ending with outstretched "ta-da" hands to usher in the song’s lead riff. They filmed it over two days in Pomona, California, a place where the band had a modest but dedicated fanbase even in its infancy.

“It was also in the time of real money for video shoots, where it was like a little movie,” Whibley says. “You had a whole little movie set. And whatever idea you had, the label was like, ‘OK, cool! Here’s half a million dollars to do that.’ Whereas now, you have an idea … well, first you have to find out what your budget is, because these days, you’re like, ‘What’s the budget we’re working with?’ and they’re like, ‘Uh, we can probably swing 15 to 20 grand.’ OK, well, I can set something in my garage for that. But, back then, your ideas were endless, and you could do whatever you wanted.”

The director, Marc Klasfeld, was known at the time for rap videos, like Nelly’s “Country Grammar.” He would end up collaborating with the band for the rest of their career, but this video was their first time working together. Klasfeld basically went around the giant party/mob scene and found people willing to do funny shit for the camera.

Once all was said and done, the band had absolutely no idea whether or not they had made a good music video. They liked it. They had fun making it. But just as Whibley didn’t know what a hit song sounded like, he didn’t know what a hit video looked like. That confirmation came from another up-and-coming pop punk band they had been touring with a lot -- Good Charlotte.

“I remember one day they were in LA while we were in LA,” Whibley says. “We happened to just bump into each other at the same hotel, and we were like, ‘We got a cut of our first real video.’ And they were like, ‘Well let’s watch it.’ We showed it to Benji and Joel [Madden], and they were, like, over the moon about it. They were just freaking out. ‘Oh my god! This is such a great music video! You guys are gonna be such huge stars!’ And we’re just like, ‘What? No way.’ And they’re like ‘This is it! This is the last day we’re gonna know you before you’re famous! You guys are famous now because of this!’ ‘Nah, we’ll see.’ It was just funny to see their reaction, because we didn’t know if it was good. So after that, we were like, ‘Maybe we do have a good video.’”

Whibley says a lot of success is timing and luck -- playing that demo for Jerry Finn before they had finished the album, releasing an album that fit so perfectly into the pop culture landscape of the moment. Although "Fat Lip" had stalled out on the charts a couple times before blowing up, its rise happened to coincide with the network’s 20th anniversary event, MTV20. Because Sum 41 were a hot new band of the moment, MTV asked them to perform the song as the first act of the night. And this is where opportunity met preparedness for Sum 41. Instead of smiling and saying thank you and playing the song and going home, they harnessed the confidence that only a group of naive 21-year-olds given the keys to the kingdom possessed, and decided to go big with it.

They had seen other big-name acts collaborate on performances at these things, like Kid Rock and RUN DMC, so they started asking around for some of their own heroes to help them out on stage. "We thought, 'Why don’t we do something like that?' And we asked a few people," Whibley says. "We asked Tommy Lee from Motley Crue, we asked Rob Halford from Judas Priest, and they said yes... We put this medley together, and we opened the show. And it was just one of those …”

He pauses.

"Everything just seemed to work out."

Having a line in the song that says “Maiden and Priest were the gods that we praised” probably didn’t hurt, either.

“From the next day, nothing was ever the same in our lives ever again,” Whibley says. “That was the day everything changed. MTV put the song in heavy rotation, the song started climbing up the chart and ended up going #1 [on Billboard’s Alternative Airplay chart]. The albums started selling and hit gold, then platinum. Around the world MTV picked it up everywhere. It just exploded everywhere.”

Sum 41 had an impossibly long leash with Island/Def Jam, but being with such a big-name and big-money label meant they occasionally had to play ball. After the success of the rap-rock “Fat Lip,” Island/Def Jam wanted them to follow it up with a track on the Tobey Maguire Spider-Man soundtrack, which was a coveted space in 2002. Also, being Island/Def Jam, the label brought in rap-rock sensei Rick Rubin to produce it. The end result was “What We’re All About,” which is actually teased in that convenience store prologue of the “Fat Lip” video.

Whibley and the band gave it their best shot, but they didn’t want to rehash something for the sake of commerce. “Fat Lip” was such lightning in a bottle, and it took so much time to get right. Even with Rubin, arguably the biggest producer in the world for that genre, it didn't work. It felt forced. It was an honest attempt from a punk band that loved thrash metal and RUN DMC equally to blend the two again for the sake of cashing in on the first wave of superhero mania of the 21st Century, but it had the exact effect that Whibley wanted to avoid when he said “Fat Lip” just didn’t feel right.

“It was a whole thing,” Whibley says, diplomatically.

“We really were against it. We didn’t want to do it. But, we got kind of talked into it, and the fact that Rick Rubin wanted to be a part of it, well, that’s pretty fucking cool, so let’s just go see what happens with it. And it wasn’t very good. And it didn’t do well. We knew we were right. We didn’t want to do it. And I think that kind of killed that idea of, ‘You have to keep doing rap stuff.’ It was just like, ‘See? It doesn’t always work.’”

So when it came time for the next bona fide Sum 41 effort, they knew they couldn’t try to make All Killer again, no matter how commercially successful it was. And they wasted no time on a victory lap, either, releasing Does This Look Infected? in November of 2002.

“The thought was to kind of become a new band almost,” Whibley says. “We considered even changing the name, because [lead single] 'Still Waiting' sounded nothing like those three songs that just came before it. It was just like, ‘Let’s throw everything out the window. I’m gonna scream over this next song, and it’s gonna all be dark, minor chords, and it’s got more of a metal kind of guitar riff throughout it. Completely different thing.’ And I think that was directly out of [being] somewhat embarrassed by the fame and success of All Killer, and also just not wanting to repeat yourself. How can we still have success but do something completely different?”

As soon as “Fat Lip” blew up, that imposter syndrome mixed with a little bit of punk rock guilt for getting so famous started to set in a little. But, rather than run from it, Whibley fed the wolf that wanted him to prove that he and his best friends deserved to be there.

The music video for “Still Waiting” -- a song Whibley also wrote at the eleventh hour of production -- touches on the breakneck pace of cultural evolution. Just one year from rap-rock and destruction being the be-all-end-all of popularity, Will Sasso’s smarmy record executive character is trying to convince the band to be more like the too-cool garage revival band like the Strokes or the Hives, rebranding them as the Sums and putting them in front of the neo-retro gold lights of a variety show broadcast.

If “Fat Lip” was, in fact, a major label looking for a “cash grab” so to speak, Does This Look Infected? was the band proving to themselves as much as the world that they weren’t a one-trick pony. They had reached a point that they knew they were capable of reaching, doing what they were meant to be doing. There was no need to fall back on that NBA career -- or worse, college -- just yet. But they had to keep that momentum going, or they’d be on the next plane back to Toronto as one-hit wonders.

Sage wisdom Whibley received from Ice-T at a party in 2003 has lingered in his memory.

“He said, ‘The only thing harder than being the mack is staying the mack.’ And it’s a lot easier to get famous than to stay famous.”

But unlike what some artists do when they feel like they’ve matured beyond their fledgling efforts, Whibley and the band never wanted to break up with “Fat Lip” or act like they were beyond it, even multiple decades, albums, lineup changes and personal milestones later.

“I think I still feel the same way about it that I did in the very beginning,” Whibley says. “The day that I get sick of playing a song that everyone knows and everyone goes crazy when we play it, and everyone starts jumping around and everyone sings it, I should just quit because I’m so fucking jaded. It’s the greatest feeling in the world. I’ve never understood that. I don’t get Radiohead, even though I love Radiohead, why they don’t play their big songs.”

Sum 41 has seen the world and achieved just about everything they could have dreamed of. Twenty years later, All Killer No Filler remains a vital time capsule of early 2000s culture -- a new-millennium aesthetic shift away from the dingy '90s to the chrome-polished and spiky-haired future, recalling its past but ushering in a new punk sound for a new generation of kids too young to remember the first Bush administration or Desert Storm. The MTV of 2001 was still playing plenty of music, but it was transitioning to the channel of reality TV and prank shows, which set a tone for the time just as much as the music.

Each song on All Killer No Filler is integral to its overall success. But “Fat Lip” has always stood out. Maybe it’s that it was the lead single. Maybe it’s how it had such an identity among the rest of the album’s relatively homogenous color palette. But people in their late 20s or early 30s have a certain soft spot for the song about about storming through the party and drinking in an El Camino -- a car Whibley had barely ever seen in person when he wrote the song. Now he might be owed at least a thank-you for the free publicity.

"I think we saw maybe one one time," Whibley says. "I remember seeing it and just fucking dying laughing, cause, like, what the hell is that thing? We just didn’t see them. I think I was like 17. And we thought it was the funniest car. And then it becomes the joke. It was always like, whenever we get our first car, it’s gonna be an El Camino. And that car always just stuck in our heads as the most ridiculous car. It’s hilarious. I still tell myself I should get one someday. I need to own one of those."