We're refreshing and revising our old Counting Down lists to make room for new albums and insights that have come along since their initial publication. Our first ranking of Björk's albums from worst to best originally ran on February 22, 2013.

Every age wears the art-pop that suits it. Often, that pop is cut in an arresting direction: perhaps arch, or giddily self-referential, or interrogative. It elicits the usual critical discussion about contradictory impulses: low and high, sincerity and irony, culture and its jamming. For much of her four-decade career, Björk has been the preeminent pop artist whose tonic note has been wonder. The dualities are present, of course. Consistent tensions have included the body and anima, the auditory and the visual, nature and technology. But her openness -- a big time sensuality, as she once put it -- tends to fuse them in unique ways.

Much was made of Björk Guðmundsdóttir's early childhood on a commune, but her home country of Iceland was, in some sense, already pretty communal. The year Björk was born, Iceland had fewer than 200,000 citizens: a smaller population than Cape Coral, Florida. Musicality was easily discerned and swiftly transmitted. At a weekly school talent show, Björk caught her teachers' attention with her rendition of Tina Charles' 1976 UK chart-topper "I Love To Love"; before 1977 was out, she had an LP -- loaded with chipper marimba pop and insistent disco -- on Icelandic shelves. She wasn't even a teenager.

Her initial recording foray aside, Björk's career in Iceland was spent forming and joining bands. There was the all-girl punk rock fuckaround Spit & Snot (for which she played drums), a jazz fusion act, the theatrically post-punk Tappi Tíkarrass (featured in the crucial '82 documentary Rock In Reykjavik). There was even a futile attempt to help a local jam band break the Guinness record for longest continuous performance. At the tail end of her time in Tappi, Björk joined an all-star sendoff assembled for a state-radio program about to be booted from the air. The collection of big fish hit it off, naming themselves Kukl (meaning "sorcery,"more or less) and rapidly signing to the heavyweight UK anarchopunk label Crass Records.

In Kukl, even as one of two lead singers (the NME once called the other one “the plainest boy in history”), Björk was recognizably Björk. You can hear the brassiness, the voice-crack she would later use to such gutting effect. When she's backgrounded, you wonder what she might have said.

Kukl called it off after 1986's continental concept album Holidays In Europe, but Björk and Einar Ørn (the aforementioned plain boy) soon convened a new act: the Sugarcubes. They were an alternative pop/rock group that initially sung in Icelandic, and their dream-pop debut "Birthday" made a big enough ruckus in Britain that a number of labels came to them. The band signed to Elektra, toured America, played Saturday Night Live: The stage was slowly rising to meet Björk.

After a small lifetime in guitar bands, she was ready to move on. In 1990, she released Gling-Gló, a conventional cafe jazz record fused to her particular voicings. She also used her pop cachet to employ and be employed by electronic artists. In 1991, 808 State featured her on their jazz, downtempo single "Ooops"; the following year, the Sugarcubes disbanded after releasing It's-It, an album of house and techno remixes. An NME profile of 808 State visiting Björk in Iceland has a revealing compliment from the singer: "They know what they want to do. They're always working towards some idea."

And so it has been with her, from the rapture of her mid-'90s pop-electronic work, to her stretching strings across the stark grandeur of her native country, to her 21st century collection of records exploring the intricacies of timbre and the curiosities of the universe. Throughout it all, she has wielded one of modern music's most distinctive and expressive voices. The searching quality of that voice -- at this stage in her career, Björk's melodic lines tend toward the discursive, with each syllable doled out after some deliberation -- and the awe that is her default mode of perceiving have helped her carve a distinct cultural space. She is an artist's artist, one who has elicited praise from all points on the art/pop spectrum. And, not least, there is her impact as a woman exercising multi-disciplinary auteurship, perpetually adding some degree of difficulty in the pursuit of some current ideal.

A note about the rankings: we've restricted the list to non-soundtrack albums of original material. So no Drawing Restraint 9 or Selmasongs, and none of her many remix albums, as illustrative as they can be about the fungibility of her work and the many contexts in which her compositions shine.

As a project, Biophilia has so many moving parts: It's a record, a series of interactive apps, a live undertaking, a music curriculum. Unfortunately, the audio portion is the most static. In order to accommodate the didactic nature of the project -- which is being incorporated into music and science lessons for Reykjavik schoolchildren -- the tracks are sparsely arranged and often showcase one instrument at a time. Still, a lot of those instruments are pretty awesome: a celesta designed to be played by tablet (specially-commissioned), Tesla coils, insanely heavy gravity harps. Were Björk looking to create a bowel-shaking avant-pop album, she could easily start with Biophilia's mad gaggle of instruments. "Crystalline" is the closest this record comes to fusing new and old Björk. A twinkling gameleste (that reconfigured celesta) and heavily edited buzzbeat back a Debut-era topline; the final minute rewards us with a glorious throwback breakbeat. In places, "Mutual Core" bangs with that old industrial feel, and Björk gets to show off a still-robust upper range. But for the most part, we're left with a slaved-over skeleton (the album's release date was pushed back in order for the record to be given more sonic vigor) that requires a host of add-ons to become a living organism.

The inclusion of Razhel, Shlomo, and Dokaka on Medúlla was, perhaps, Björk's sly suggestion that she was ready to foreground beats again. One of the people to help her? Timbaland, who gets three production credits on Volta. It makes some sort of sense; if Björk had debuted in 2007, it's possible that she would have turned to the likes of Timbo -- who was in the midst of his production Silver Age -- instead of electronic musicians. While Volta was refreshing in its redbloodedness, it's remarkably flabby for a running length of just 51 minutes. The album was released in different configurations -- some outros became intros -- which meant that for some releases, each of the first three cuts are over five-and-a-half minutes long. It's an eclectic mix of sounds, to be sure: Four continents contributed players, helping Volta run the gamut from American to Zombo. And it’s not as if Björk had been saving up all her instrumental ideas since Vespertine, either: In 2005 she released Drawing Restraint 9, the soundtrack to the feature-length film by visual artist Matthew Barney, her romantic partner at the time. Though more formless than Volta, it similarly employs an extended cast (Will Oldham, Vespertine harpist Zeena Parkins, shō master Mayumi Miyata) and far-reaching arrangements. The result of this cultural smash-and-grab is a record that smacks of curation, rather than collaboration. Konono Nº1's electric likembés are overpowered by Danja's synthbass and Timbaland's distorted "whoas." While the return of the long-dormant coy vocal flavor was a welcome thing, the references to voodoo and muddy bodies are beneath Bow Wow Wow, let alone Björk. "Hope" is a fine showcase for Malian kora player Toumani Diabaté, but Timbaland's contribution to the pattering throwback is difficult to suss out. Anohni's second album appearance (on "My Juvenile") is one too many; she does acquit herself well on "The Dull Flame Of Desire," a brass-fortified duet of ominous triumph. (Oddly enough, the stirring horn arrangement of "Wanderlust" evokes, in retrospect, Hercules And Love Affair.) Volta is certainly not bad -- how could it be, with a cover that stepped straight out of Pepperland? -- just overstuffed. Its simpler tracks tend to be the better ones. "Vertebrae By Vertebrae" focuses on pneumatic drum programming and horn honks suited to a film noir low-speed chase scene. Returnee Mark Bell, back in the fold for three tracks, provides the album's highlight: "Declare Independence," an electro-punk fusion that goon-stomps into the red with claustrophobic bass and and carelessly triggered cymbals. There is fun to be had on Volta, but it must be extracted.

Everything surrounding the creation of Vulnicura was difficult save its actual recording, so co-producer Arca returned for a follow-up which promised to be freer. It was the Venezuelan who suggested the placid "Pagan Poetry" B-side "Batabid" as a possible guidepost; both producers contributed birdsong recordings from their birth countries as interstitials. The resulting album is typically open to all without and within, as Björk airs Vulnicura's balladic form out even further. Besides the birds, the key instrumental feature here is the tredectet of flautists, providing melodic/rhythmic scaffolding and a human extension of the sampled warbling. (An expensive Utopia box set included a collection of birdcall-mimicking, one-hitter-looking flutes.) A stray quip about Utopia being her "Tinder record" fueled a news cycle, but her real love seems to be the internet. "For him a he/ Is WWW," she croons over a vaporwave plink-and-'plode; elsewhere, she rhapsodizes about sharing MP3s with someone. Falling into the net, flirting behind a screen, speculating on cryptocurrency (album purchasers received 100 Audiocoins, which are currently trading... not high) -- she is typically prescient here. She pairs her urban unease with an understanding of the city's rituals -- DJing a Brooklyn club, creeping on a bearded record-store shopper. And while the record has some of her funniest lines -- "The handsomest of wicker men"! -- the unmistakable sense is that the titular utopia has a strong technological component. As a psychospiritual portrait of a wealthy, tech-adjacent creative in middle age, Utopia is a rich text. As a paradisiacal text, well, the way is narrow.

The title rather self-consciously marks this as the starting point, but the Sugarcubes had made Björk a known quantity. After casting about for collaborators -- she approached 808 State's Graham Massey, jazz multi-instrumentalist Corky Hale, and the Art Ensemble Of Chicago -- Björk settled on Nellee Hooper, best known for his association with Massive Attack. While many of the songs on Debut were composed years earlier, the difference between this and the rather stiff art-pop of the Sugarcubes is astounding. Though her electronic bent gets the most attention, it's her interest in jazz that courses through the set. Opener "Human Behaviour" (her first single and first UK hit) rolls along on irresistible loping bass and timpani, with Björk riding behind the beat. The chill portrait "Venus As A Boy" plays like a globe-trotting torch song, combining Talvin Singh's tabla and string arrangement (recorded in India) with plummy, laconic bass. Featuring a sort of call-and-response between singer and brass (and nothing more), "The Anchor Song" is a pure jazz tone poem, as if Rahsaan Roland Kirk wrote a tribute to the Icelandic shore. And, of course, there's "Like Someone In Love," the album’s lone cover and a Jazz Age standard. She acquits herself well, working her way toward unruly passion over an arrangement of Hale's harp, synth and backgrounded street noise. It's a fine counterpoint to the previous track, "There's More To Life Than This," an anti-party song that features club ambience and perhaps the worst pronunciation of "ghettoblaster" ever. Hooper's trip-hop and house contributions don't play quite as well, nearly thirty years on; as usual for Björk, her best songs tend to achieve synthesis. (The ebullient "Big Time Sensuality," with its roller-rink organ and joyous high notes, is a major exception.) But even in the presence of four-on-the-floor beats and Chicago-style piano, she creates distinctive documents. Nautical imagery (boats, anchors, jumping into the sea) recurs frequently, as if, even at the outset of her ambitious course, Björk wanted nothing more than to escape. In a sense, she had: Her arrangements on Debut showcase her impeccable vocal chops, too often shouted down in the past by reverb-heavy pop/rock production. She sounds utterly free. And the public responded, beyond her label's wildest expectations: All five singles were British hits, and one ("Big Time Sensuality") scraped into the US Hot 100 thanks to a video that received major play on MTV. She mapped her ambition well, and fortified her position on the follow-up.

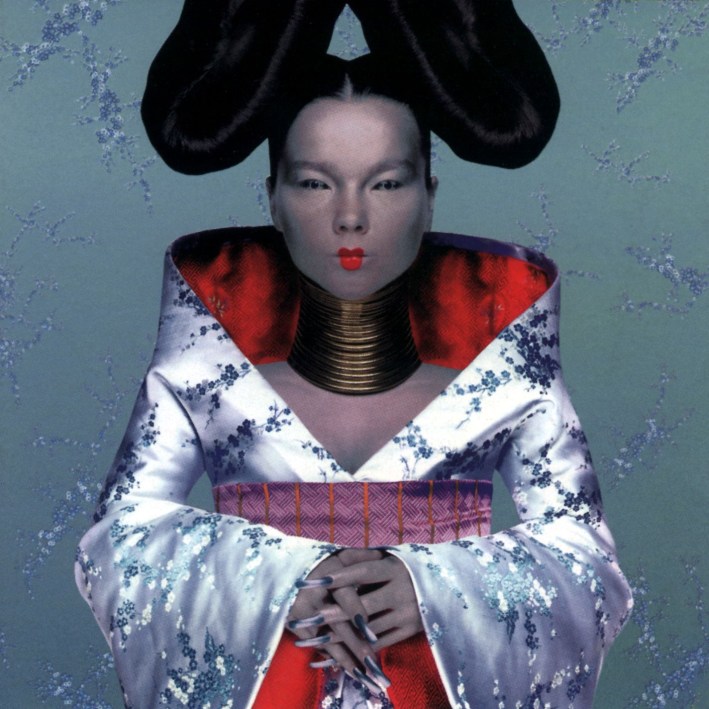

It's tempting to say that after Homogenic, there was no direction but down. Vespertine is the settling of the previous record's tectonics: the angry beats Björk made with Mark Bell are made microscopic with the assistance of IDM artists like Matmos, Matthew Herbert, and Thomas Knak. The orchestral lushness remains; indeed, this album boasts the most romantic treatments in her catalog. Thematically, this is a domestic work about, as Björk sighs at midway point "Aurora," the “utter mundane." "Vespertine," literally, refers to eveningtime, and while Wikipedia quotes her as saying "Vespertine is little insects rising from the ashes," it could also refer to the time to reflect on the day's labors (or lack of same). "How do I master the perfect day?" she asks on "It's Not Up To You," "Six glasses of water/ Seven phone calls." (It's worth noting, for the hell of it, that the brief bassline sounds eerily like Michael Ivins' work on Yoshimi Battles The Pink Robots.) The six-minute "Unison" closes on a slightly treacly note (calls to "unite" usually end up that way), but still offers a cheeky self-portrait of the singer as a bearded, pipe-smoking hermit, and offers the line "I never thought I would compromise" as contented clarity. To complement to her puttering beats, Björk spends much of the album at an intimate volume -- parceling out her phrases deliberately -- turning the grandiosity over to a new element: choirs. In theory, the choral arrangements are well-suited to the twilight feel, but they’re turned to so often it threatens the balance of the record. If the Harmony Korine co-write "Harm Of Will" is, as it's often claimed, about Will Oldham -- and the stilted syntax and skeezy sexuality would seem to indicate as much -- then the choral treatment pushes the track into the realm of high comedy. (More effective is the chorus of Björks that creak out "she loves him" on the buzzy, pulsing "Pagan Poetry.") There's something similarly heavy-handed about the use of music box, which appears on three straight tracks, including the superfluous solo instrumental "Frosti." Regardless, the record is on the whole more pretty than precious, and the turn from the controlled chaos of Homogenic toward classical beauty was one that few musicians would dare to make. Neither would many artists literally wear their record's theme, as she did in the infamous, Marjan Pejoski-designed swan dress. (The dress has its own Wikipedia page.) Björk was drawn to the swan as a symbol of monogamy and winter, and she wore the dress on the album cover, at every stop on the album tour, and at the Academy Awards. The swan may yet alight in the first paragraph of her American obituaries, which is more than absurd.

The completion of Biophilia's multi-platform presentation allowed Björk a clean break. Having become, in effect, a software product manager, she was now free to focus on songwriting. A 2012 operation to remove a polyp from her vocal cords restored her sonic depth of field. After charting the configurations of the universe, the next project would almost by definition be smaller in scope. Then, her relationship with American artist Matthew Barney ended, so that scope became domestic. Vulnicura was written in a tumble, bearing some of Björk's most plaintive and plainspoken sentiments ever. It is a literal record of disintegration -- six of the nine tracks are dated in relation to the split -- as well as recalibration. "A juxtapositioning fate/ Find our mutual coordinates" is the opening couplet of lead track "Stonemilker," a stately, patently gorgeous processional. Across the record, Björk seeks the new shape of things, as her family's "miraculous triangle" shatters into divergent lines. The set is all ballads, created from Björk's modernist string arrangements and programmed commentary from co-producer Arca, fresh off her contributions to Yeezus. On the pre-break portrait "Lionsong," the strings project an Old Hollywood reverie as the percussion quietly grinds its gears. Closer "Quicksand" maps Björk's pain upon her mother's, and ultimately onto a celestial/matriarchal lineage. It's the liveliest track -- hospital-grade drum'n'bass melting into a swaying meditation -- and it's her narrative capstone. For as much as the press made of "Black Lake" (billed as her "10-minute Matthew Barney diss track"), "Notget" was the real fire, with Arca's PVC percussion hammering home the new family arrangement. "After our love ended/ Your spirit entered me," she intones. "Now we are the guardians/ We'll keep her safe from death." Scope doesn’t get much larger than that.

For a young Björk, singing connected her with others, and allowed her to assert herself as a part of the stark surrounding geography. She would sing on buses to keep her classmates awake, and next to lava fields to demonstrate her belonging. The primarily a cappella Medúlla, then, was a reintroduction to her intrinsic instrument, a drastic experiment in exposure. (Having said that, Medúlla is careful not to overstay its welcome, clocking in as Björk's second-shortest studio album, after Homogenic.) At the same time, this is also her most political album... in a sense. The track "Ancestors" -- a piano-backed, vocal showcase of nonsense phonemes, loudly drawn breaths, and senseless dialogue -- is actually Medúlla's thematic centerpiece. In a 2004 interview with XFM, she described "Ancestors" as "going back to the roots -- before time, or civilization, or religion, or patriotism." Her sort of paleo politics is much more effective when it's approached from the edges, and her inclusion of classical choral work (including, finally, an all-male section) and beatboxing make this more than an exercise in imagined nostalgia (plus, the beatboxing supplies a bit of the funk she'd been neglecting). Whether going creepy-crawly alongside Mike Patton on "Where Is The Line," riding Rahzel's beatboxing and Tagaq's throat singing on the alternate-universe Natasha Bedingfield single "Who Is It," or going medieval on the Icelandic-language "Vökuró," Björk's vocals evince the particular mix of intelligence and intuition that was credited to her productions in critical heaps. Admittedly, this is a record devoted largely to ideas, rather than songs; still, cuts like "Who Is It" and "Triumph Of A Heart" (which features -- shit you not -- meowing) demonstrate that Björk had not forgotten how to structure a pop tune. The aforementioned two tracks, as well as the Robert Wyatt feature "Oceania," even charted in a handful of European nations. Her range was always impressive; Medúlla just quantifies it.

Similar to Debut, but with more: harder beats, a greater sense of interiority, and further exploration of Björk's vocal range. The approach extends to the artwork: Jean Baptiste Mondino's black-and-white portrait of the singer -- clad in a sweater, hands clasped before her lips -- is succeeded by a garishly vibrant, Stéphane Sednaoui-shot image. Lead single "Army Of Me" set the tone. It's an all-time great single, the kind of imperious, audacious modern rock that always eluded Trent Reznor. A menacing, bassy keyboard ostinato and live-sounding drum programming pin you to the ground; the refrain pairs Björk's famous couplet "and if you complain once more/ you'll meet an army of me" with lowing divebombs. Some of these songs were written by Björk and 808 State's Graham Massey before Debut; Debut's producer Nellee Hooper returns, joined by trip-hop titans Howie B and Tricky, her romantic partner at the time. His contributions are "Enjoy" and "Headphones," written during a trip to Reykjavik. On the former, he converts his penchant for cool menace into nagging industrial, punctured by clipped brass stabs; the latter is a complete stylistic break, a delicate, textural lullaby topped by a bravura vocal performance, combining sotto voce and multi-Björk ecstasy and pure wordless vocalization. Already a gifted singer, on Post Björk claims even more space for herself. She shifts between effortless clarity and her trademark abandon, letting her multi-tracked vocals drift from foreground to background. The trip-hop/chill out fusion "Possibly Maybe" seems to chart a relationship from uncertain outset to cessation; the singer backs herself with judicious use of a Hollywood Golden Age vocal mode. In a more explicit nod to her beloved post-war pop, she covers "It's Oh So Quiet," a German composition made famous by Betty Hutton. Björk tracks Hutton's arrangement meticulously, down to the music box and unhinged "WOW!" She has fun camping it up, but the track's a bit precious, best sampled as a palate-cleanser during the course of the record. As usual, "It's Oh So Quiet" became a hit on the back of a striking video, in this case a postmodern Busby Berkeley homage filmed by Spike Jonze. Post marked Björk's commercial peak; her two UK Top Tens ("It's Oh So Quiet" and the winkingly-titled "Hyperballad") are to be found here, and the baggy ode to anticipation "I Miss You" was her final hit on the US Dance Club chart. Her critical and commercial capital at an all-time high, she staged a retreat of sorts. 1996 found her touring the world and issuing the remix LP Telegram. In August, she decamped for Spain, ending her creative partnership with Hooper. She had new powers to summon.

The one-time anarchopunk from Iceland was now a global pop star, staging shows from Israel to China to New Zealand, collaborating with Europe's finest producers, and going platinum all over. But she could not elude the attendant insanity of fame. She made headlines in 1996 for thrashing reporter Julie Kaufman at Bangkok International Airport. (Had this occurred a few years later, there's a good chance the footage would have been more viral than any music video.) She claimed the paparazzi had been harassing her and her son, and that Kaufman in particular had been pestering her for days; in any event, Kaufman did not press charges. In September of that year, an American exterminator named Ricardo López mailed a sulfuric acid bomb to the singer's London home before shooting himself in the head at the end of a disturbing video diary. The package was intercepted in time, but the incident shook Björk profoundly. López was obsessed with his conception of her as a kind of daughter -- though he was just 21 -- and angered by her relationship with the British drum'n'bass musician Goldie. Already prepared for the next stage of her career, Björk resolved to distance herself both from her playful image and the London electronic scene that had infused her output to date. Out of the tumult came Homogenic, a towering electronic document that, true to its title, achieved an astounding cohesion. It's a rigorous work -- both in the structure and the singer's self-examination -- that never forsakes the human. Co-produced with LFO's Mark Bell, Homogenic pushes electronic forms past their breaking points, animating them with live instrumentation. The tension between Bell's skittering, sputtering beats and the Björk-moving-on-the-water arrangements -- courtesy of the Icelandic String Octet -- is exquisite. On "5 Years," the absurdly playful beat explosions and 8-bit keyboard programming race against a romantic string ascension. The swooping strings of "Joga" buttress Björk's frank declaration of a "state of emergency" before ceding, halfway through, to a muted passage that’s essentially proto-dubstep. "I thought I could organize freedom," she noted wryly on lead track "Hunter." "How very Scandinavian of me." Even as the production scales to IMAX size, Björk maintains an incisive interiority, stocked with arresting phrases and sardonic humor. The poppiest track, "Alarm Call," plays like futuristic new jack swing; against a funky bassline, she imagines herself "on a mountaintop/ with a radio and good batteries" (chuckling as she sings this the second time) -- adding, "I'm no fucking Buddhist, but this is enlightenment." She's not wrong. As a deconstructive document, it's every bit the equal of Radiohead's Kid A. But Homogenic reclaims identity; Kid A laments its loss. The record concludes with "All Is Full Of Love," perhaps Björk’s most enduring composition. It exists in two main forms: the music-video version, and Howie B's remix, which appears on Homogenic. On both mixes, Björk projects a devotional majesty, a paradoxically gentle grandeur in the vein of Sinead O'Connor. The album version opens with an elongated, pulsing string passage. As Bell introduces fluttering accordion and hiss to the mix, Björk dials up the intensity to match before conceding to the synths. The final verse is a sort of call-and-response, with castigations ("You just ain't receiving/ Your phone is off the hook/ Your doors are all shut") contrasted with the simple fact of the title. The kind of big time sensuality achieved here is captured by Chris Cunningham's landmark video, which depicts two robots kissing passionately while being assembled by machinery. It is here that Björk moved from idiosyncratic dance savant to full-on sonic explorer. There would be no going back.