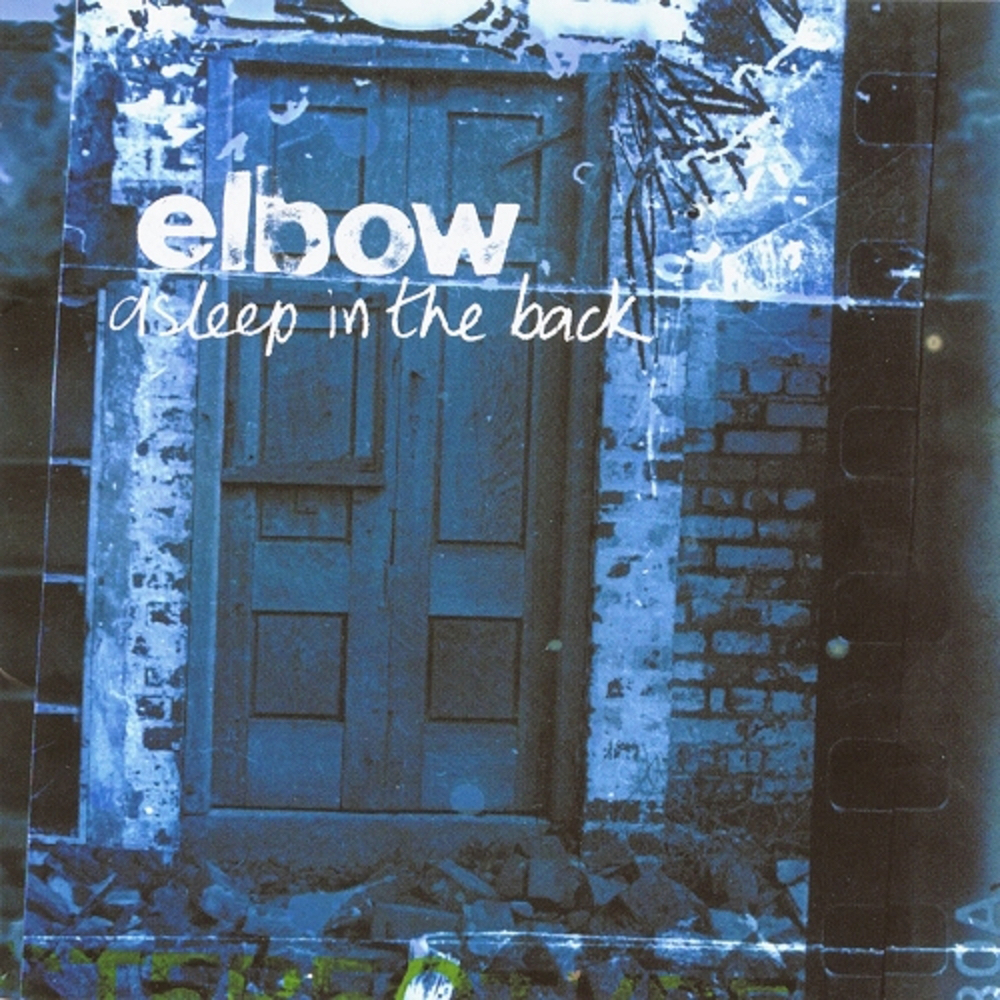

- V2

- 2001

In the beginning of the '00s, Elbow emerged from a transitional time in British music. By the turn of the century, Britpop had thoroughly fragmented and faded, but it was still a few years before a new wave of spiky, bratty English rockers would rise up. In the interim, there was post-Britpop, a genre murky in both aesthetic and definition. What we mostly remember now is a handful of bands that seemed to follow in Radiohead’s wake -- more atmospheric and lachrymose than their typically more colorful Britpop predecessors. Coldplay were the biggest, eventually crossing over into full-blown pop stardom. Doves and Travis released beloved albums as the '90s gave way to those nascent 21st century days. Then there was Elbow, a band that been soldiering on for years already and finally released their debut album Asleep In The Back 20 years ago today.

In some form or another, Elbow had already existed for a decade. An earlier iteration of the band gestated in high school, when Guy Garvey met Mark Potter, who recruited him to sing in a band with his friends Richard Jupp and Pete Turner. By the late '90s, they’d rechristened themselves Elbow, shuffled lineups, and were gearing up to release a debut on Island Records. That deal fell apart, and the group had to re-record what would become Asleep In The Back. After a few more years slugging it out, they signed with V2 and released the album in the spring of 2001 -- just in time to catalogue the "21st century hangover" Garvey had already been anticipating, a moody sense of drift on the other side of seeming sea change. (That was in the UK. Elbow would have to wait even longer for their debut to hit US shores, where it arrived in early 2002.)

It’s hard to imagine now, the possibility that Elbow could’ve actually released music in the '90s. Perhaps they wouldn’t have been all that shocking of an outlier, with Radiohead running parallel to Britpop themselves. But when Asleep In The Back came out in 2001, it felt very much of its time and place. The whole album was bleary, nocturnal, rain-soaked, alternating between haunting stories and nostalgic flashbacks both warm and unpleasant. They were right at home in the misty post-Britpop wave, and they were often compared to artists that had little influence on '90s Britpop -- the aforementioned Radiohead, U2, Talk Talk, the Blue Nile. Garvey's voice was immediately and constantly compared to Peter Gabriel’s, and Elbow's wistful art-rock owed a great debt to Gabriel as well.

All of this came together for a debut that was an immersive listen. "Any Day Now" kicked the whole thing off with a trip-hop beat nodding to another Elbow inspiration, DJ Shadow, and it was a perfect curtain rise on Elbow's world. They still don’t have many songs like it. There's some kind of mechanistic sheen to the song, a feeling of rote repetition, chanting "any day now" as a promise to yourself that you’ll get out of the grey surroundings of your youth. For Elbow, the dead-end hometown in question was the Greater Manchester suburb of Bury. (The more guttural trip-hop of "Little Beast" was also a reflection on their childhood there.) If "Any Day Now" was about that classic impulse to get out and see the rest of the world, it was a fitting overture for Asleep In The Back — thematically, and in terms of how the album would change the band's life irrevocably.

From there the album was an empathetic and evocative series of different characters and scenes -- the sort of collection you often find in a debut album or debut novel. Garvey wrote about friends and family and memories. "Red" was about a friend with a drug problem, while "Powder Blue" picked up a similar thread, describing a couple Garvey once saw in a bar who were coming down off of something at the same time. In moments like these, Elbow's patient arrangements served them well -- the aqueous guitars and piano cascades of "Powder Blue" set a fittingly blurry scene, before the song rode out on wordless vocals and sighing saxophones. In some ways, Elbow already had great sense of catharsis in their music. But the same as "Any Day Now," many of these songs were about people trapped in certain cycles and situations, as in how "Bitten By The Tailfly" turned the weekend party scene and hookups into a particularly primal overflow of noisy guitars and tumbling drums.

But at the same time, Asleep In The Back was far from a bleak album. There were moments of comfort, bonding, hope. One of the album's calling cards was its sprawling centerpiece "Newborn." At various points, Elbow were sometimes regarded as a proggy band, and the band once called themselves "prog without the solos." "Newborn" might be the best example of that scope and ambition in Elbow's earlier days. The band have said they were trying to imitate an orchestra with "Newborn," and the result is a lush, gorgeous song that built to a stunning climax, airy organs and spiraling guitars and Garvey’s intensifying vocals before crashing waves of distortion led the song out. It was a rush, soundtracking a story in which two lovers imagine growing old together.

In many ways, Asleep In The Back remains Elbow's darkest album sonically and thematically. "Newborn" was a big bleeding heart overflowing in the middle of the album, as if it was there to try and heal the surrounding songs. It was more indicative of where Elbow would go as a band in the future, but it wasn't alone. At the end of Asleep In The Back's long, foggy journey through the night, you had "Scattered Black And Whites." All these years later, some fans still regard that as Elbow’s finest song -- and they might not be wrong. Over a gentle acoustic guitar and sputtering piano interjections, Garvey reflects on childhood snapshots, tumbling back through the years. "I come back here from time to time/ I shelter here some days," he sings in the chorus, underlining how powerful his gruff voice would become when he’d found his muse, the past and nostalgia. More than the eerier corners of Asleep In The Back, this is where Elbow would settle over the years. Their catalog is full of meditative songs in the vein of "Scattered Black And Whites," but even at their best they've rarely matched the original template.

Most of these post-Britpop bands weren't necessarily "cool." They were too earnest, or detractors could find them dour or maudlin. But there was a richness to Elbow's stories, and a gravity to Garvey as a frontman and storyteller. Asleep In The Back arrived to a feverish round of acclaim. As the British press does, they coronated Elbow; you can even find old reviews saying they were nearly on par with their beloved Radiohead. The album was nominated for a Mercury Prize. After years of struggling to find their footing, Elbow's debut set the stage for a career that, at least in their native UK, has been immensely successful.

While Elbow were never exactly a hip band, Asleep In The Back accrued a level of media buzz they probably never matched again. They did, however, keep growing. After Asleep In The Back's successor Cast Of Thousands, the group started developing a slightly more straightforward version of their aesthetic. Eventually that led to 2008's The Seldom Seen Kid -- arguably their best and most notable album, and the one that actually won them the Mercury Prize. Now they're an establishment in their homeland, filling arenas and leaning more into the U2 part of their sound than the Radiohead. As the years went on they became known for swelling, sad-euphoric choruses, songs like "One Day Like This" becoming their trademark. Garvey would tap into big, universal feelings, and he could sing them in a way that made a whole bunch of people in a field want to sing them back to him.

Knowing what came later, you can draw some through lines from Asleep In The Back, but it also feels like a very different band. Elbow were already reaching the end of their twenties; they weren’t green, per se. There was a world-weariness to their debut, a wise (or worn) beyond their years quality. But at the same time the darker shades of Asleep In The Back now feel like a final purge of youthful listlessness. There's still plenty of yearning across the ensuing two decades of Elbow music. Over the years, their whole framing of that flipped. In the beginning of the '00s, Elbow emerged in a transitional time for British music, but they also emerged from their upbringing, their initial context. Any day now, they were going to get out. When they did, they instead turned their eye to capturing the spectrum of human experience not with melancholy, but with wonder.