- Loma Vista

- 2021

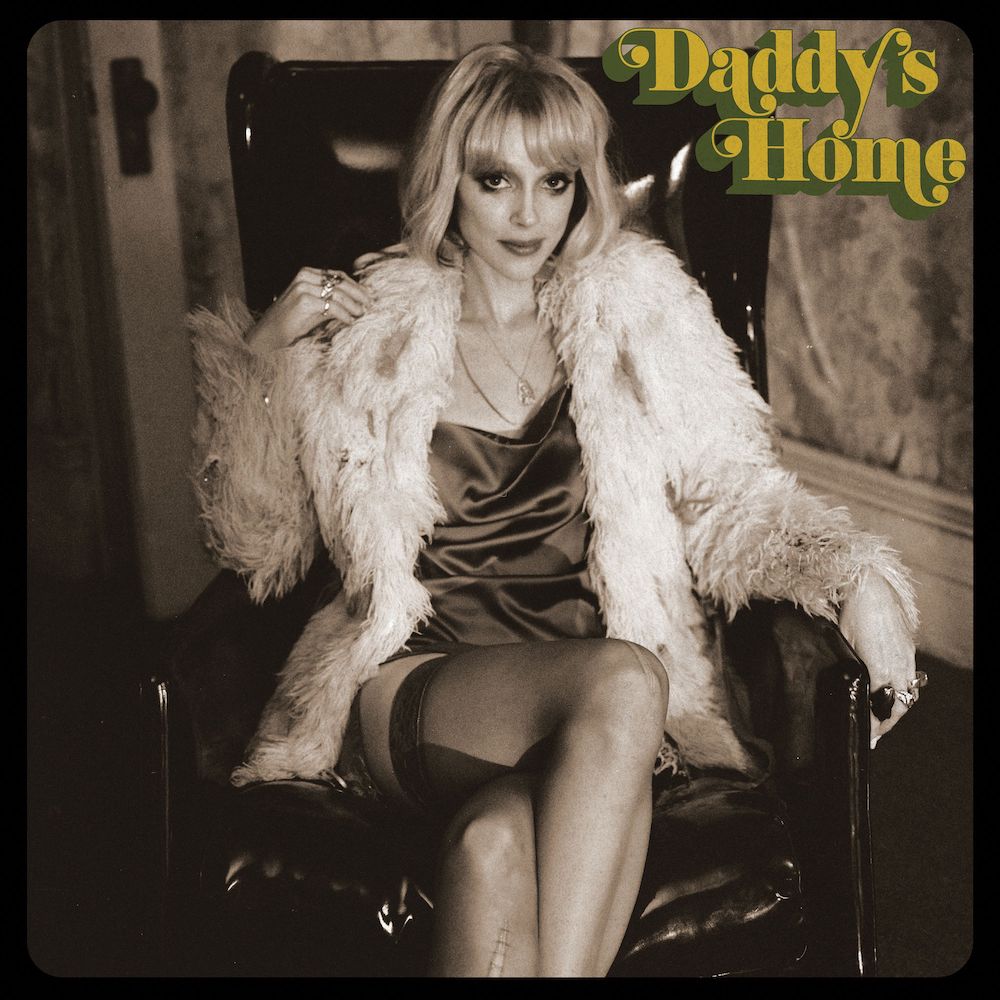

Every St. Vincent album is its own character. That’s long been the case and it has long since garnered her comparisons to artists like David Bowie and Madonna, pop's great shape-shifters. Though plenty indie artists of her generation chose a moniker for what are actually solo projects, Annie Clark has used “St. Vincent” to the fullest extent — an empty name, ready to be filled with the narcotized distance of Strange Mercy or near-future cult leader of St. Vincent or the bugged-out, lurid dominatrix of Masseduction. When Clark first started rolling out Daddy’s Home, it seemed the character was the biggest left-turn she could choose at this point: A normal, broken-down human.

Daddy’s Home comes with one of the barest personal narratives Clark has offered in years, being partially inspired by her father’s release from prison after 10 years. While in hindsight there were lyrical glimpses of his incarceration way back on Strange Mercy, Clark never talked about the situation at length, and then it became a story within the tabloid attention that swirled around her high-profile relationships. Daddy’s Home was an opportunity to tell the story her own way, which in turn yielded a series of character sketches she described as “flawed people doing their best to survive.” It’s an evocative premise, and in order to tell those stories Clark delved into a new aesthetic shift that seemed a perfect backdrop.

“I felt I had gone as far as I could possibly go with angularity,” Clark said when announcing Daddy’s Home. Instead, she dug back into the records of her youth: Steely Dan, Stevie Wonder, Bowie. Daddy’s Home was positioned as a warmer, more lived-in collection steeped in the big comedown of the ‘70s and specifically the sleazy, druggy glamor of ‘70s New York.

On some levels, Daddy’s Home is remarkably successful in meeting that prompt. Partnering once more with Jack Antonoff, Clark holed up in Electric Lady and crafted an album drenched in alluring signifiers of the ‘70s. There’s squelchy funk synths, smoky organs, soul backup singers, the occasional psychedelic zone-out, and a trippy sitar-guitar that steals the show on a handful of tracks. Once she leaned into that musically, the narrative followed. In its best moments, Daddy’s Home effectively captures the characters Clark was drawn to — the woman with heels in her hand getting home from a night out while others start their days, a person losing their shit at a party, everyone as bedraggled and frayed at the edges as the ‘70s mythology Clark was drawing upon.

Daddy’s Home’s peaks are when the iconography and sonic details dovetail perfectly. The “Fame”-esque “Pay Your Way In Pain” first seemed like it wasn’t necessarily that much of a departure from Masseduction, with its jagged danceability and sawing synth bass. But it works as an overture to the grimy world of Daddy’s Home. Right after, there’s the more worn and wistful “Down And Out Downtown,” a train ride south through Manhattan riding on a cresting chorus and that sitar-guitar. The instrument reappears in a few places, notably for a deeply infectious riff on “Down,” the punchiest song on the album and one of the only times where Clark does something a bit more uptempo and catchy on Daddy’s Home.

Much of the album is surprising in how consistently mellow it is, and sometimes that results in special moments — the subdued gallop of “Somebody Like Me” is a gorgeous echo of old-school St. Vincent (with its ‘70s stylings resulting in a lap steel rideout that’s almost My Morning Jacket-esque). Then there’s “...At The Holiday Party,” a beautiful sigh that would’ve been a powerful closer to the album. On the other side of Daddy’s Home, it’s the clearest moment of redemption — an acknowledgment of the unhealthy ways we cope and spiral out, Clark teasing out a subtle but entrancing melody over carefully deployed percussion and horn murmurs.

Clark may have felt she had pushed angularity to its limits, and at one point that might’ve suggested she had pushed artificiality to its limits. But Daddy’s Home is instead almost suffocated by conceptualizing. The album’s aesthetic is thoroughly realized, but along the way some of its songs are inert or half-baked. After a strong beginning, you get to the title track, and St. Vincent’s newest form immediately begins to feel more like pastiche. Clark’s theoretical shape-shifting actually always progressed logically — an ascension that played out over the course of, at least, her last three albums. As she tries to lean into a guttural funk, yelping her way through “Daddy’s Home,” it quickly starts to feel like a bad fit for Clark’s talents.

Though there are few severe missteps — alongside “Daddy’s Home,” the one that comes to mind is “My Baby Wants A Baby,” Clark’s odd flip of Sheena Easton’s “9 To 5” — there are a lot of wearied-in-the-wrong-way moments across Daddy’s Home. Thematically, it’s all on-point, channeling a deeply strung out vibe. But musically, it often makes you wish Clark was pushing it further in some way. “Live In The Dream” is an airy, pretty song, but what should be a spacious prog ballad instead starts to feel like a claustrophobic drift. That song sits right in the dragging middle of Daddy’s Home, otherwise partnered with the aimless “The Melting Of The Sun” and “The Laughing Man.” It’s also paired with one of three humming interludes, which do nothing to help the feeling that Daddy’s Home has a shaggy, unfocused arc. Again: It nails the prompt. With those asides and murkier tracks, Clark has approximated a sprawling ‘70s hang. But when put against songs like “Down” — where she takes that history and makes it thrillingly her own — you’re left wondering about missed opportunities.

There are other uneven St. Vincent albums. When Clark hits, she’s still capable of some of the most idiosyncratic and memorable songs of anyone going right now. The more disconcerting aspect with Daddy’s Home is the general retro bent of it all. For all that’s been made of Clark in a lineage of classic icons, one thing that was always true — especially relative to a lot of her peers in a nostalgia-driven era — is that she was always creating something that felt wholly her own. Each new iteration of St. Vincent was more futuristic than its predecessor. Now, for the first time in her career, she has looked to her past and upbringing, but this doesn’t necessarily lead to the openness implied in the rollout of Daddy’s Home. The character of St. Vincent is as cold and removed as ever, but now there’s a cognitive dissonance running through the entire premise of the music.

This was, eventually, bound to happen with a project as conceptual as St. Vincent. But following the addicting Technicolor madness of Masseduction, Daddy’s Home feels like a big ‘70s comedown spiritually, too. A few years ago, you could only imagine how much further out Clark could go from the warped, wired sounds of her ‘10s albums. She was always unpredictable and always finding new textures that seemed impossible. Now, still, who knows where St. Vincent will go next; it’ll obviously be somewhere different, as it always is. But Daddy’s Home makes it clear that the project works best when Clark is looking toward far-off horizons, not retracing the past. Daddy’s Home was plausibly an opportunity to go back to Clark’s own origin stories to rewrite St. Vincent, incorporating some her personal history more explicitly. Instead, it mostly feels listless and lost within its own distant universe — one that we recognize the language of but one with a graininess that, this time around, keeps new revelations at bay.

Daddy's Home is out 5/14 via Loma Vista. Pre-order it here.