We’ve Got A File On You features interviews in which artists share the stories behind the extracurricular activities that dot their careers: acting gigs, guest appearances, random internet ephemera, etc.

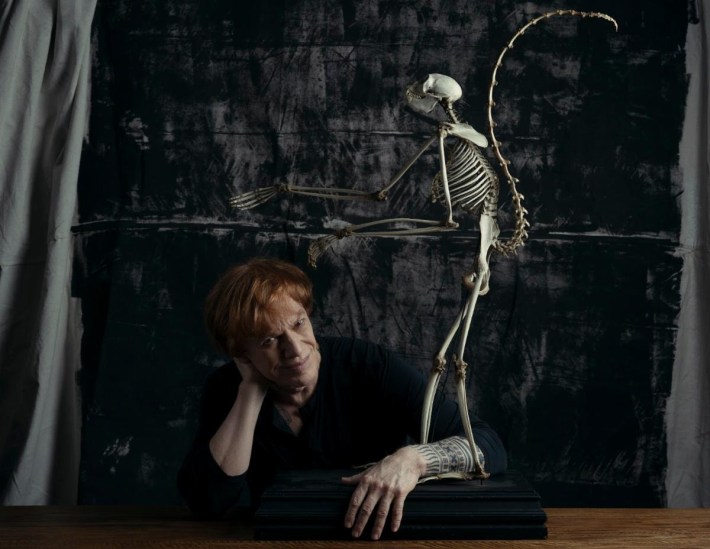

Even if the only thing Danny Elfman ever did was The Nightmare Before Christmas, he'd still be the GOAT. Of course, the 68-year-old musical maestro's score, soundtrack, and voice work on Tim Burton's classic stop-motion animated musical -- the type of cultural artifact that's truly timeless, passed down across generations in a way that very few works of art are -- is far from the only thing he's done across his mind-blowingly prolific career. He's provided the scores to over 100 films and counting and acted as principal singer-songwriter for the seminal new wave collective Oingo Boingo before the band disbanded in 1995.

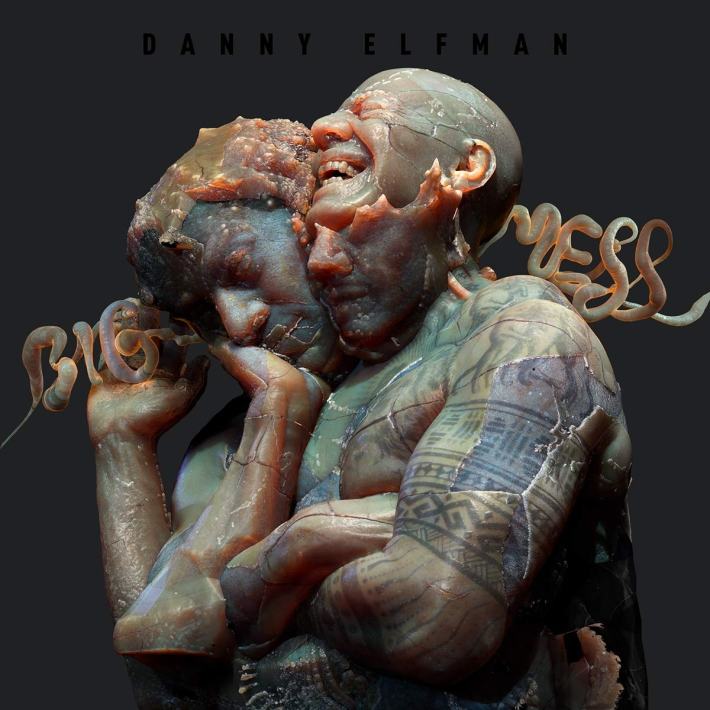

His latest act? A solo artist, again: Earlier this month, he released his second-ever solo album of compositions, Big Mess, on Anti-. Essentially an accidental follow-up to his only other work under his name, 1984's So-Lo, Big Mess came about when the world stopped due to the COVID-19 pandemic. Along with a lovely discussion of his extensive career as a musician -- from touring with French avant-garde troupes and portraying the devil on film to miming as a rocker in Rodney Dangerfield films and getting the piss taken out of him on Family Guy -- he detailed the tireless, nonstop creative mindset that brought about this latest endeavor: "I'm always gonna be like, 'One more song, I can get it right.' The way my mind works, unless I have some whistle blowing that cuts off, I won't stop. I'd still be working on Pee-wee's Big Adventure trying to get it right if I didn't have a deadline."

Touring With Jérôme Savary's Le Grande Magic Circus (Early 1970s)

This was essentially your first professional music endeavor.

DANNY ELFMAN: It was really amazing. Six months before I was performing mandolin and violin with them, I hadn't played anything. Music wasn't even part of my agenda. It was insane. It was such a 180 from where I thought I was heading in life. I was only 18, and up until 16 I really thought I was going to pursue a career in science, and then visual arts because I was interested in film. I thought I'd become an editor or cinematographer. Music was not on the list. And then suddenly it was like, "What is this?" It was one of those radical things that happens in our lives where it's totally alien, but I was digging it. It was the beginning of getting bitten by the performing arts bug.

You're someone who's had a hand in making music for tons of movies. Given your early interest in film, what were some of your early experiences in movie theaters?

ELFMAN: What I primarily remember about my youth was going to movies virtually every weekend. The movie theater was my church, for all practical purposes. I lived within walking distance of one in Los Angeles, and every time I went there with my brother it was filled with boys. It was a crazy era with all these science fiction, monster, and adventure movies. It'd be two movies in the afternoon with two or three shorts beforehand, and it was noisy and boisterous, with ushers pulling boys into the lobby and telling them to stay there for five minutes and calm down before returning to their seats.

I was 12 when I had my first musical experience with movies, and it was The Day The Earth Stood Still. It was a wonderful science fiction film, but what stuck with me was the score. I loved the music, and I saw the name "Hermann" at the end of it. If you'd asked me the following year what my favorite movie was, I'd say whatever film had Hermann and [stop-motion animator] Ray Harryhausen, like Jason And The Argonauts.

The first movie of my life that I was told I wasn't allowed to see was Psycho. Our parents didn't know what the fuck we were seeing ever -- we just marched off to the movies, and they were really gory, but no one cared. Suddenly, Psycho comes out, and I say, "OK, I'm heading to the movies!" And my mother says, "No no no, that's not going to happen." I'd never been told "no" about a movie in my life! But Psycho caught so much press about sexual overtones. And I was really upset, because I really wanted to see it but I couldn't. It was the only movie of my youth that I was restricted from seeing.

When did you end up seeing Psycho?

ELFMAN: Later on, as a teenager. The first Hitchcock film I ever saw in theaters was The Birds. I loved it. I started going to retrospective houses around that time too, and what a great film education you'd get. Two movies every night for a dollar -- Kurosawa and Polanski, Hitchcock and Truffaut. Every night that I wasn't rehearsing or waiting tables, I was at the movies.

The Mystic Knights Of Oingo Boingo (1974-1979)

You joined this early form of Oingo Boingo after some time busking in Africa.

ELFMAN: It was a different band entirely. All acoustic, no electronic instruments. We called ourselves a "troupe." It was 12 people, and everybody had to play three different instruments. We'd be a string ensemble playing Django Reinhardt, and then we'd switch it up to a brass band with Duke Ellington and Cab Calloway arrangements, and we were a percussion ensemble too. It was this great exploration of early 20th century music, and I was such a nerd -- I've always been OCD -- that in the 1970s, I wouldn't listen to music recorded after 1938. I just wasn't interested. In my mind, I lived in 1933.

The only music I'd ever studied was gamelan, so I brought that into the troupe as well. I went secretly as a non-student to CalArts for three years -- and I'm admitting this now with some guilt, because I never paid tuition and I'm not anywhere in their records. [Laughs] I literally just showed up and started playing. I also brought in these marimbas from West Africa into the troupe called balaphons -- they have a gorgeous resonator, so we loved playing those, but they were too delicate to bring around, so we built our own. For years, me and my cohort Leon Snyderman would grind metal and wood to get the tone.

There was a part of my life where I considered being an ethnic musicologist. But the most important thing from those years was teaching myself how to write and notate music. It's where I discovered my ear. Because as I was doing these Ellington and Calloway arrangements, I wanted to write them down. So I had to teach myself how to notate from scratch. It was really hard, but I learned that if I heard a phrase on a record, I could freeze it in my mind, write it down, and get it just right. I'd be listening to vinyl over and over and carefully notating the phrases. Without that self-training, it's unlikely I would've got into film [scoring] later. It was a lucky accident.

Acting As "The Devil" In Forbidden Zone (1982)

https://youtube.com/watch?v=zimsUDzOiSM

ELFMAN: It's totally my brother’s film, and when he asked me to do the music, I did three or four songs. It was during the changeover between the Mystic Knights ending and Oingo Boingo beginning, because we were starting to play some electronic instruments -- so we broke that magic shield. So my brother caught us right at the beginning of what was going to become Oingo Boingo. It was fun, it was just his thing. People ask me about the creation of it, and I always tell them it's Rick’s baby.

He was the one who appointed me as musical director of the Mystic Knights. He picked me up after I got back from Africa. I had a case of hepatitis, and he said, "I know you’re sick, but why don't you start listening and soaking it up?" While I was watching this street troupe rehearse, I was like, "I'm supposed to be the musical director?" I learned to pick up trombone and drums, and I learned to breathe fire. I picked up all these bizarre talents that didn't come into play later, except the notation. Right after Forbidden Zone, that's when I heard ska and I thought, "I really want to be in a band. I don't want to do a troupe anymore." It took days of setup and preparation for us to do a show at that point, and it was a hugely complicated maneuver. Suddenly, the idea of being in a band and needing nothing but our amps and guitars and drums seemed really appealing.

You mentioned how you've picked up a lot of talents over the years. Have there been moments where you've felt insecure about your own abilities?

ELFMAN: [Laughs] I'm sorry, I have to laugh. The question is when don't I feel doubt? Every time I start a new project, I'm just filled with doubt. That's never gone away. It doesn't matter if I've done 110 films or 10 films. I start out with the same insecurities, and I always feel like I'm dropping an empty bucket into a well, and I can't see the bottom, and I have no idea if I'll find water. That's what starting a project feels like. Doubt is the centerpiece of me beginning any piece of work.

Maybe the exception would be Big Mess, which was driven by necessity. I wasn't thinking, "Am I doing the right thing? Is this good or bad?" There was a moment where I just didn't care. It was about things exploding out of me that needed to come out. I had moments where, at some point, something happened so quick that there was no time to doubt it because it was instantaneous -- a dozen moments where I took a first glance at something, and I heard it in my head and that was it, with no struggle. But those moments are in the minority. Most of the time I'm sitting down and going, "What the fuck do I do? Do I have anything left in me? Am I washed up?" And this was even when I was 35! But at a certain point, I go, "There's something that's a little interesting, I’ll go with that."

Oingo Boingo Cameoing In Back To School (1986)

ELFMAN: I don’t remember a lot about that. I was doing the score -- it was my second or third -- and they said, "Hey, how about your band appear in this scene and play onstage?" I was like, "I guess? I don't know?" What I remember most was meeting and hanging out with Robert Downey Jr., who was the sound mixer mixing us while we played.

Any memories of meeting him?

ELFMAN: We talked and really liked each other, and then we met many years later on Doolittle. We hadn't talked in 30 years, but it felt totally normal. I don't have a lot of memories about this one, though. Shooting a scene in a movie is always weird. The makeup, the waiting, the lighting, the sets, doing things again and again. But that's filmmaking, I understood that. I can't say it was fun, but it was a new experience. Whatever. It seemed kind of cool in the moment. I don't know.

Oingo Boingo Retiring (1995)

This took place during an important juncture in your life where you were dealing with hearing problems.

ELFMAN: I'd been thinking about it since the late '80s, and I was in a conundrum. I realized in hindsight that I was not wired to be in a band. I was always frustrated, and every other year I wanted to be in a different band. I never had a sense of who I was, or who we were -- and I still don't, and I've reconciled with that now. But when I was in a band, I always wanted to do something different. I hated touring unless it was really short. Six weeks was the most I could stay on the road without going insane. There was a certain point where I realized I was not cut out for this, and I'd go crazy having to play old material over and over every night. I admire artists who are good at that, who can find it in them to do the same night every week -- and performers in the theatre, who might have to do it for years. Wow! How the fuck do they do that? It's one of those great, mystifying talents. Whatever that is, I didn't have it. I'd just be climbing the walls.

I have a very short attention span. Whatever I'm doing, I want to be doing something else -- the opposite -- really quick. The thing that worked for me in the second half of the '80s and in the '90s is that I was suddenly a film composer and in a band, and whichever one I was doing I wanted to do the other one. Whenever I was on the road, I'd be like, "I can't wait to go work on a score and write a new piece of music every day where I never have to repeat the same piece." When I was in the middle of a really hard film score, feeling tortured and working insanely long hours -- in the beginning, I used to work 14-16 hours a day, seven days a week -- I'd be like, "Oh my God, I miss being at the Whiskey A Go-Go, covered in sweat and feeling that freedom of physical expression, letting off energy."

The problem is that I was successful as a composer. The point in the '90s where I really wanted to leave -- and I started saying to the band every year, for about five years, "This is our last year," and they were all like, "Whatever, go do your fancy film composing and make a lot of money." I felt really guilty about that. I didn't want it to seem like I was leaving the band because the other thing was more lucrative. That guilt kept me going for at least five years. Come '95, it was totally fucking up my hearing, and when my father died in his 80s, he was legally deaf. I realized I had it genetically, but I was getting blasted every night too. I started developing tinnitus, and I said, "That's it -- I have to stop."

Even if I didn't want to stop, I had to stop. At that point, we had in-ear monitors, but I didn't trust them. They were starting to come out, but I was afraid of them. I'd been blasted by feedback in the studio with headphones so many times -- blasts that put you out of commission for an hour. It was like having a bomb go off. I was afraid it would happen with an in-ear monitor and I'd be gone. It made me super paranoid, with all the bad experiences I'd had with headphones. So I'd reached a point where [quitting] became as much of a physical necessity as it was a psychological necessity. So in 1995, I said, "This is really it. We're gonna say farewell after this concert." And that was it.

The Nightmare Before Christmas (1993)

You have a lot of singular milestones in your career, but being involved in a classic work of art beloved by children and adults -- it's a rare experience.

ELFMAN: I consider that film to be a real blessing of my life -- if there were any blessings. There were plenty of curses. I never worked on a film more than three months prior to that, but with The Nightmare Before Christmas I was working for two years. It was more involved than anything I'd ever done for film. It was a really long, drawn-out project, and I was there at the very beginning with Tim before we had a script. We were doing the songs because we didn’t know where else to start.

When the movie came out, there was so much confusion. No one knew what it was, Disney didn't understand it or know how to market it. There was this general perception that kids hated it. I had this very depressing two-day press junket at Disney World in Florida, where every single interviewer asked, "So if it's not for kids, who's it for?" I'd go, "No, that's not true." And they'd go, "We hear it's too scary for children." And I'd go, "No!" Then they'd go, "We hear Santa Claus gets tortured." And I'd go, "No! He's not tortured! He's terribly inconvenienced, but he's not even that upset by it." It was this constant repetition.

Disney were used to The Little Mermaid and Beauty And The Beast, and this was not that, so they had no idea what it was. It came out and disappeared really quickly, and it broke my heart that it was so misunderstood. So for it to regain a second life caught me off guard, because so few films get that. There's just a small handful of movies that actually pick up steam after they came out, that for any project I worked on for that to happen to... because I've worked on a lot of unsuccessful projects. More than half [have been], if not two-thirds.

But I really poured myself into The Nightmare Before Christmas. There was a lot of my personality in Jack's character, even though he was conceived by Tim. As I wrote the songs, I was feeling what Jack was feeling, so I was like, "I know this guy. He wants to get out of Halloweenland and he doesn't know how, and I want to get out of being in a band, and I don't know how." We both wanted something else, but we didn't know what, and we didn't know how to get out of our own kingdom that we felt defined and imprisoned by. So I really understood Jack and poured a lot of my own psyche into fleshing out his own character with the lyrics.

The great feeling when I started doing the shows live -- which I still enjoy doing, for a while longer at least -- is all the kids in the audience, and all the feedback I get every year with people sending me videos of their kids singing the songs. It's vindication, because I always knew that kids love Halloween, and if you're not scared by Halloween, you're not scared by The Nightmare Before Christmas. I'd say in the press junket, "It's no scarier than Halloween," but they just didn't get that. The fact that it's been embraced by generations of young audiences is really a great feeling. I really love that. Every song I wrote I played for my then-10-year-old daughter, and she heard them all and would give me her input. So I knew the thing wasn't too scary for a 10-year-old girl, but no one else knew that.

They had one catastrophic preview for kids that made no sense. The film wasn't finished, there were pencil drawings here and there. The kids were going into a Disney animated preview, and they were all expecting The Little Mermaid, so it didn't go well. I remember hearing executives go in the elevator after the preview, "Well, kids hate it," and after that all the marketing completely stopped. It was pretty depressing. They had all this free merchandise for McDonald's that stopped cold, and my agent scrambled to get all the free merch he could. He said, "This is all gonna be valuable in the future, I'm gonna put my son through college with this." And he was right.

Family Guy Parody (2007)

https://twitter.com/famguynocontext/status/1124690144446042113?lang=en

Family Guy parodied you and your style of music as part of their Star Wars parody episode.

ELFMAN: [Laughs] Yeah, I saw it.

How did it feel to be parodied?

ELFMAN: It was very surreal. I didn't know what to make of it, except that the piece of music they had me playing was really ridiculous. I was like, "Oh my God, I've been reduced to that." It’s one thing to be personally parodied. That's fine, I don't care about that. To hear my music badly parodied? Ouch. That stung a little bit. But I know it was all in good humor, so it was not a problem. Every songwriter and composer is a little bit sensitive. It's an insecurity that you carry forever.

When you hear yourself reduced to a bad parody of what you've done previously... look, there's full of musical ouches in the world. I'd always get involved with the videos for Oingo Boingo, and the one I didn't was "Weird Science," because I was composing. I literally just showed up on set and let someone else put it together, and I always regretted that. It was the video I was always embarrassed by, and years later I was watching Beavis And Butt-Head and there I am on "Weird Science." All I remember thinking is, "I asked for this. I can't blame anybody but myself. I deserve this, and now I gotta be okay with it." [Laughs] I still love the visual side of things though, and one of the things I love about Big Mess is that we did seven videos. That's been really fun.

Performing With Oingo Boingo's Steve Bartek For The Nightmare Before Christmas Show In Los Angeles (2015)

You noted at this show that the performance was 20 years to the date of the final Oingo Boingo performance.

ELFMAN: Right, but you have to understand, I work with Steve every year. I love working with him. On Pee-wee's Big Adventure, I needed an orchestrator, and I turned to Steve and said, "Have you ever done orchestration?" He said, "I took a class at UCLA!" I said, "That's good enough." It was his first time orchestrating, my first time composing. He went on to work with me on -- if I did 110 films, he did at least 95 of them, if not 100. For this performance, I said to Steve, "I'm doing an orchestral rendition of 'Dead Man's Party,' how'd you like to put on a guitar?"

When the show got booked at the Hollywood Bowl, I thought it was insane. I said, "This is a little thing -- a little movie, a little show." When it sold out, I thought, "Oh my God, I have to do something extra." It's a very short movie! So I pulled up "Dead Man's Party," because it was Halloween, after all. I asked Steve if he’d like to play it with me, and he said, "Sure!" It wasn't even a big deal. Suddenly we were there playing "Dead Man's Party." It was one of those things where you just realize it's 20 years since you've done this. But it didn't feel weird -- it just felt like what we do.

Big Mess (2021)

You mentioned earlier that this project -- essentially your second solo album ever -- came out of necessity.

ELFMAN: It was a perfect storm of elements happening at the same time. For one, I was enormously angry and frustrated about America and what was happening to it in 2020. For the first time in my life, I was thinking, "We may have to pick up roots and get out." I saw a civil war coming, and I didn't know if I wanted to be around for that. I felt like I was living in a George Orwell novel -- as if he'd written a sequel to 1984 called 2020. That's what 2020 felt like to me. I had a lot of venom in me, and I didn’t realize it until I started putting lyrics to the song "Sorry," which started everything. I had to let that venom out somehow.

Also, 2020 happened to be the year I took no film work because I wanted to give the whole year over to concerts -- and, of course, 100% of them were cancelled. I was probably the only person ever to be booked at Coachella that was going in with nothing to start with -- no band, no show, no nothing. I spent three intense months putting it together once I agreed to it, and I was really inspired by doing a show of extreme contrasts: a mish-mosh of retooled Oingo Boingo songs against film music, but with all these visuals. In 2019, my manager dragged me out to Coachella, and I thought the sound system was amazing, but the screens... it was such a technological leap from the last time I'd been at a concert. They were so big and vivid and able to carry strong imagery.

So I put three months of work into that, and it got cancelled three weeks before the show. I was just at the point where, for the first time in a quarter-century-plus, I had an electric guitar in my hand and I was singing and rehearsing with other musicians -- and it all just exploded. So there was a big depression that came out of that. All that energy, and then nothing. On top of that, there was isolation and quarantine and being cut off with most of my family except for my wife, my 16-year-old, and my dog. I wasn't alone, but I have a big extended family that gets together every week, and I was cut off from all of them. When I finally came out of a month of catatonic depression and realizing the whole year was going to be a wash, and I started working on a commission for the [BBC] Proms, even though everyone knew nothing was going to happen anyway.

I had a couple of pieces I'd already prepared for Coachella, and I thought, "Maybe I'll get a few companion pieces together and put out an EP." I didn't know what to do with myself. In my house, I had a studio with a modest writing room, one microphone, and one electric guitar -- I didn’t even have a pair of headphones that work, and I wasn’t going to have a tech come in and look at my stuff at that time. It was in that frame of mind that I started to write, and it was just like opening Pandora's Box.

So around August, I had 18 songs, which was plenty. Then there was the process of arranging to play the music for record companies, which was a huge challenge. We'd make an arrangement, everybody would isolate, we'd all get tested, four of us would meet in my studio -- two record company reps, my manager, and myself. This happened a half-dozen times, and then I'd go back home and isolate from my family for a week. My daughter set up a table outside of the dining room where I'd be eating outside away from the rest of them, and she'd say, "Just pretend it's a restaurant, dad -- this is an exclusive table." Enough days would go by, I'd get tested, wait 48 hours, and then I'd rejoin the family again. It was very challenging.

With this new material, I'd get all this interest from different companies, but my manager would tell them, "Understand that it's not what you're expecting to hear. It's not Oingo Boingo." I take a weird pleasure to play things for people that they're not expecting, so I always led the presentation with "Sorry" because I just wanted to see their faces. [Laughs] It was almost like performance art. I'd look at their expressions, usually horrified, and take great pleasure at that. Andy from ANTI- was at the office and was far from shocked. He stood up and applauded, and he wanted to talk about it for 10 minutes before I could even play the second song. I was like, "OK, I think I know where we're heading with this." He understood what it was and where it came from. It just made sense to him.