We’ve Got A File On You features interviews in which artists share the stories behind the extracurricular activities that dot their careers: acting gigs, guest appearances, random internet ephemera, etc.

There are a ton of reasons to be a fan of Tom Scharpling. His sense of humor's both broad and deep without being cheap or condescending, he's an ideal advocate for being a music head with all the quirks and foibles that come with it, and his very being seems to be animated by the drive to stand up for the underdog. A master of social media back when that meant "call-in radio show host" and not "Instagram influencer," Scharpling's The Best Show -- started in 2000, initially a staple on greater NY/NJ-area freeform station WFMU, now a streaming show and after-the-fact podcast -- also gave rise to the decades-long comedy partnership of Scharpling & Wurster. With Scharpling as the often-confounded straight man to Jon Wurster's rotating cast of miscreants and mutants, one of the greatest drummers in rock (Superchunk, Bob Mould, the Mountain Goats) also proved to be one of the funniest people alive. If all they'd done was come up with the Fonz-inspired greaser sociopath The Gorch or the Always Sunny-outdoing ur-Philly mayhem vector Roy Ziegler, they'd still be cult legends.

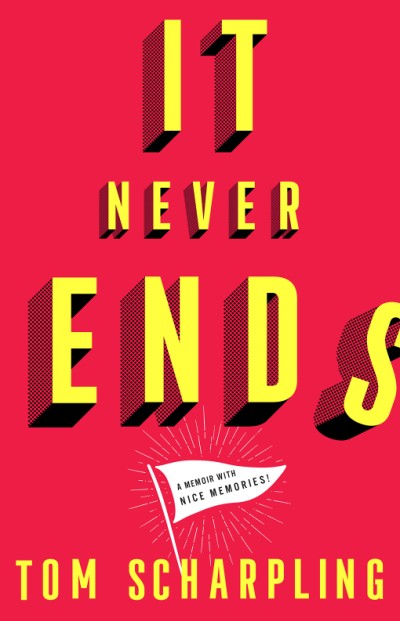

As it stands, Scharpling has advanced beyond semi-obscurity and into this odd but fitting space between culthood and fame. Yes, Rob Gronkowski (to cite a name Tom disbelievingly drops) would probably be a more recognizable name to put on your bookshelf, but Tom radiates enough charisma in his prose to make you wonder why the football man beat him to bookstores in the first place. And if a skeptic might look at It Never Ends: A Memoir With Nice Memories! as something strictly for diehard fans, it's also the kind of book that makes it known just why Scharpling has so many diehard fans, and why he deserves more of them. The tone of confessional depth mixed with freewheeling goofiness -- put to use in a stark, plainspoken style that reveals how much pain and frustration went into making Scharpling the man he is today -- is so welcoming that it's easy to forgive the odd digressions and tonal shifts.

This is a memoir where the author includes an entire chapter dedicated to his lifelong obsession with arcade games, which would seem like a bizarre detour in anyone else's autobio but feels here like a deep dive into Tom's constant drive to prove himself. That, and some of Scharpling's other stories -- his perfunctory tryout for the New Monkees, which he dodged a bullet by failing; his years channeling an enthusiasm for music into fanzines and friendships; his relentless efforts to finally turn his comedic chops into a radio showcase of his own -- take on the weight of revelatory heaviness with the new context of his recollections of his times struggling with mental health. This included an inpatient hospital stay during his high school years, where said recollections become hazy due to electro-convulsive therapy being part of his treatment -- a process that damaged his memory, leaving many of his youthful experiences a vague blur. But even with that obstacle in place, it's still easy to find something relatable in Sharpling's scattershot reminiscing, all his comedy and music heroes clicking into place en route to making him who he is today.

Narrowing Scharpling's experiences down to a handful of events, even focusing on the musical side of his interests, is a daunting task. I'll leave some of the best bits for readers to discover in the pages of It Never Ends -- Scharpling's proposed slapstick music video treatment for Paul Simon, a mortifying attempt at conversing with Mickey Dolenz, a disastrous Election Night 2016 with a startling coda soundtracked by Perth post-punkers the Scientists. But in singling out some of the formative moments Scharpling had in music, both from the book and elsewhere, our conversation took an unexpected but welcome turn into philosophizing about music fandom, countercultural trends, and why being a polymath beats staying in one lane every time.

Meeting Patti Smith And Asking Her About Humble Pie For Some Reason (2015)

https://youtube.com/watch?v=uk3zNyvFGvk

This is early on in your book, where you talk about staying in the same hotel as Patti Smith during your time at SF Sketchfest, and after spotting her a few times you finally work up the nerve to introduce yourself. But since you're still kind of reeling from the death of your father a few weeks previous, all you can come up with is a memory from a year before where a cabbie you rode with in Memphis talks up how great Humble Pie were. So you ask her if she saw them back in the day, and she was utterly confounded by the randomness of the question.

SCHARPLING: Yeah, that was… that was something else. That was some kind of day. And it was one of those things where it was like, wow, as it was happening, it's like, this is one of those. It didn't just go well. It's not like, "ah, that was okay" or "eh, it wasn't much." No, that was a seismic shift in things not going well. And feeling the magnitude of it was like, OK, this one's gonna stick around.

Yeah, it's the syndrome of "Oh, I want to ask a question that she hasn't been asked 100 times before," but then you get so far at the other end of esotericism, that it just completely waylays her.

SCHARPLING: It is. The worst is like, I can feel it as if it just happened when I think about it.

But one thing it kind of leads me to wonder is, you have a pretty wide range of interests when you're talking about rock music. When I grew up reading about music, the general thing was like, you could be punk rock, or you could listen to this arena rock AOR stuff -- never the twain shall meet.

SCHARPLING: Yeah, absolutely. No, that was how it was. Especially as [my] very formative years, late '70s into the '80s. It really was, pick what team you're on because you can't be on more than one team at a time. I remember Creem magazine just being like, if you like Led Zeppelin, you cannot like the Clash. And if you liked the Clash, you don't like Led Zeppelin. And the fans hated each other. They would fight in the letters pages. And you're like, wow, the lines are being drawn here. And it was funny to watch over the years, the lines start to dissipate to where you'd have kids just start to be like, no, I like Hall And Oates. And I also like the Eagles, and I also like something great. Oh, okay, wow, you just like music. Good for you. And there's something very positive about that. But it's also very strange when you grow up with everybody being like, what you liked was your identity.

I don't see that as much in other art forms. Like you don't have people all, oh, I like samurai movies, and they like Westerns. So we're gonna go at it.

SCHARPLING: I mean, you do have... look, Marvel vs. DC is ridiculous. They're both superhero movies. And those guys have picked up the mantle of this, I think. But that's about it. The outliers would be the superhero people who want everyone to convert to superhero-isms. And they're just like sore winners at this point. Now, they can't take it that Martin Scorsese, this 78-year-old man, doesn't like superhero movies. They feel like he must be jealous because they make so much more box office than him. I'm pretty sure he's not jealous of any movie. Especially some superhero movie.

I feel like being a poly-genre enthusiast is kind of like, well, you go through different moods. Sometimes you want to go Bad Brains on somebody. And sometimes you just want to get into a Joni Mitchell vibe. It's a very personal sort of connection that I think really kind of drives different ways of just being in the world.

SCHARPLING: If you're into hardcore, I can't picture just being into hardcore. It's like, how does that work? Oh, you only want to listen to hardcore? That hardcore matches every mood you might be in? Hats off to you if that's where you're at, but I can't picture one style of of anything fitting all sizes.

An Incredibly Crummy Time At A Billy Joel Concert (1984)

https://youtube.com/watch?v=B_b-F8BoJT8

In high school you got an unexpected invitation to join two of your cool jock classmates to go see Billy Joel live at Madison Square Garden. This did not go well.

SCHARPLING: Yeah, we had the tickets, and one kid... we tried to sell his ticket to a scalper because [this kid] had a bad, bad day trying to buy a switchblade [NOTE: He was conned into spending $20 on a candy bar in a paper bag], and he was like, "I'm out." And the scalper was just like, "These are the worst seats in all of Madison Square Garden." And they really were! It was spectacular how bad the seats were. If they were two rows closer, it wouldn't be nearly as bad. It was literally the last row behind the stage. So it's like when things are that bad, it actually becomes kind of magnificent in a way. Because it's just like, oh my God, we're getting the absolute worst version of this. I actually get excited when things are at that level. I don't know what that says about me.

Especially when he actually turns to address your section, or that side of the arena, for one song. [It Never Ends ballparks it as "Just The Way You Are," "maybe his most nauseating song."]

SCHARPLING: Oh, yeah. For one song he acknowledged us, as if it was like a contractual obligation to do that. Like you cannot sell the seats if you're not going to acknowledge those people for one song. It was spectacularly bad. And I was not a fan of his. I [knew his music] insofar as you hear the crap on the radio, and it's like, it just was there. It wasn't like I liked it. You were just exposed to it all the time.

Yeah, to me he feels less like a larger than life personality and more like ambient malaise. Like that bit in Uncut Gems where Howie's driving, feeling awful, and "The Stranger" comes on. It's a vibe where even this overfamiliar song gets a kind of malevolent stench to it.

SCHARPLING: That captures the Long Island of everything with that movie. Howard would be like a Billy Joel guy. And you just know that would be one of his patron saints. Billy Joel out there is Prince to Minneapolis, or Springsteen to New Jersey -- he's a god. But Billy Joel is just like, I don't know. There's just less there than with the other icons.

Discovering The Monkees (1986)

You talk about becoming a fan of the Monkees at a particularly important time in your life. You're definitely steeped in these dual enthusiasms of comedy and music. And they were really right up there with the leading lights of that sort of fusion -- they're kind of like pop art comedy in a lot of ways.

SCHARPLING: To me they were a prefabricated thing that should have just stayed a prefabricated thing, but there were too many ideas and too much excitement about the time, all the change in the '60s, and they wanted to be a part of it. They kind of forced the hand of this corporate thing to to be more real and less corporate. And it's a very strange thing. It's like Pinocchio or something where it's just like, they want to be a real boy. And one way or another they made that happen, and they kind of did become that. And on the corporate side of things, they were getting the best songs from the best songwriters. So they were kind of armed with these songs in their back pocket that were unbeatable. And they were great performers and enthusiastic and funny -- so it's a weird confluence of things that could never happen again.

Yeah, they're kind of like in this odd liminal space between acting and music. Not a lot of artists really have that level of success crossing over into both worlds. You have musicians who become actors, where there's a handful of decent ones, and then you have actors who try to become musicians -- and that's not as successful. But the Monkees are a very interesting case of showbiz and rock music intersecting. And it's a precursor to all that poptimism talk -- you can get any kind of real deep satisfaction from any kind of artists, just as long as they strike a nerve with you, whether it's a fully independent singer-songwriter, or somebody with a huge team of writers.

SCHARPLING: I mean, there was a shift at a point where suddenly performers were supposed to be songwriters as well as performers. And that was such a relatively new concept at that point. But look, they had Michael Nesmith -- he wrote amazing songs. He wrote "Different Drum" for Linda Ronstadt before he was in the Monkees. And that was a top 10 hit. And he wrote songs that were as great as any songs the Monkees had. he was writing, Peter Tork wrote basically the best stuff on the Head soundtrack, which is their best album, in my mind. So they had these skill sets that were kind of laying in wait or underutilized, that they kind of forced it to the force the issue to where they started to get their songs on albums, and got to play on the albums and drive the force of the thing. I mean, it was over within three years. But they covered so much ground in those three years. And it's a strange thing, because again, the concept of singer-songwriter stuff was not some entrenched thing -- it was a brand new idea that the bands were judged by whether they could write the songs also.

Meeting Jon Wurster And Chronicling Indie Rock (1992)

You hit it off with Jon pretty quickly -- obviously you went to go see Superchunk [on a bill at the Ritz with My Bloody Valentine and Pavement] because you were a fan of their music. And then it turns out, meeting him after the show, the guy has the same kind of comedic sensibilities as you, bonding over things like the Chris Elliott show Get A Life. That's real lucking out there.

SCHARPLING: It's very strange. And it's very fortunate for me in every possible way that that happened. Because it was like, everything was kind of waiting for me when Jon and I got together, we were able to get so many things going. And we completed each other in so many ways. I was kind of waiting the whole time for some kind of partner to work with, and to have somebody who understood where I was coming from. And the idea that this TV show was was the thing we we had in common? That's the luckiest break ever.

That was something that also came with your zine-writing years. You had 18 Wheeler and you were working on your voice throughout that.

SCHARPLING: Fanzines are the perfect thing if you're trying to get your voice down. It's a great form to do that. Because you're your own editor. And you could decide what the tone of your fanzine is, and you write about what you want to write about. You don't have to run it past anybody. It's a great way to get your stuff in front of people. And I think that's why fanzines even with all of the way technology is now, there's always going to be people who want to hold things in their hand, and read something that they're physically holding on to.

I just think there's something so powerful about fanzines -- if I was waiting to get things published, it never would have happened, because you have to earn your clout with stuff. So you can show people what you do, rather than... they're not going to hire anybody if I'm just like, "Trust me, I'm good. I'm telling you, I don't have anything I could show you. But I'm good, you should probably hire me for a thing." No, they're not gonna hire you! They need to know what you bring to the table. And that's a great way to cut your teeth and kind of figure out how you write, and what works and what doesn't work and how to get better at all of it, how to interview people, everything.

So many skills that I learned came from doing fanzines, it was just a fantastic learning technique. And it was a way for me to be funny, I decided mine was going to be funny, but it was also going to be enthusiastic about music. And I could just kind of focus on both of those things. And some things would be funny, some things would be straight, it was just like a reflection of how my brain worked. You create the fanzine that you want to see, and that you'd want to buy. I think if you're doing it right, that's what you're trying to do. If you wrote one that you yourself wouldn't buy then that's like the worst thing imaginable. I always love everything I learned from doing a fanzine because you got to learn how to sell the thing too. And distribute the money that somebody owes you for it. So many things come from from putting a fanzine together. Like every other part of my life.

The Best Show On WFMU (2000)

I think the interesting thing about The Best Show is that it's very in tune with music fandom, and not just because of what you played as a DJ. I'm thinking of how you put it, like, in the early years, people didn't want to hear your comedy, they just went "play some music!" But the thing is that your show is so entwined with the music world that it just became a music show in itself. I mean, you play records, obviously, and brought in bands to appear on the show as callers or live in the studio. But I feel like you've kind of really cultivated this sort of, I'm not sure if I'd call it a scene, but definitely kind of like a nexus of indie rock and punk and garage rock.

SCHARPLING: Yeah, I mean, I don't know. It's so funny. It's like I've never identified with just one type of anything, I've always been interested in the better parts of any style. And that's why we're proud to be open for anything. I like quiet stuff. I like loud stuff. I like old stuff. I like new stuff. I like deliberately retro stuff... I never identified with one specific lane of anything, I've always bounced around. And it's the same way with like, I was interested in writing about music. And I was interested in writing funny stuff, writing about music, doing radio, directing stuff, writing for TV shows, that it just was like, I just carry a lot of interest simultaneously. And I kind of want to do all of them, and be a part of all of them. There's a part of me that wishes, what if I was totally into Bob Dylan to the degree where I just knew lyrics backwards and forwards and knew live shows and all that stuff? Yeah, that I understand the appeal of that, but I just couldn't do it. I never have been able to dedicate my interest to just one thing ever. There's always other things that start to spark my enthusiasm. And I want to I want to know about all of it.

Yeah, that's a very positive attitude to have, I think especially nowadays, you have this attitude that, oh, everything's available. You don't have to invest a lot of time in dealing with trying to like something you don't like, but on the other hand, you're never more than a couple degrees away from something you didn't realize you'd like.

SCHARPLING: I mean, when I wanted to buy an album, there's an album I wanted to find, like looking for like the NEU! albums, or in high school looking for the Beach Boys album Sunflower, and would take months to find these things, or to win an auction for a record in Goldmine magazine through record dealers, or going to shows and record stores looking for these things. And when you got it, it's just like, man, you better give it your full attention. Because it's a lot of work just to get a hold of it just to gain access to that music. Now you could put a thing on and check it out and just start playing a game on your phone while listening to it. And you don't have to give it your entire attention. I think it's great that stuff is accessible. Now I think that's a massive improvement. Because then it just democratizes all of it, that you can just have access to it. It doesn't have to be for who can go to a show or who can afford $50 for an album. But also I personally appreciate the circumstances that made it so you wanted to respect the thing that took so long to get ahold of, and it made me listen very closely to certain things.

But then as a DJ, you get to actually put forth the idea...I'm not a fan of the term curation. But to be able to put a sort of a seal on something and play it and say "I trust you to like this," I think is a very important thing whether they're a DJ, or just some schmo making playlists. Probably one of the more important things you can do in music is to actually link things together, and basically be able to articulate why this feels like something that you could connect with a listener.

SCHARPLING: Absolutely. I feel like you kind of have to earn the position a little bit, if you're going to be telling people, I would like that they should listen to this, and they should care about this. There's a responsibility to that. If people are making this music, you don't want to just burn through it. I feel like you got to respect it. It's just like, I would hear stories of rock critic friends or acquaintances, who'd be like, "yeah, I wrote five reviews this weekend. I'm exhausted." Oh, man, I would not have wanted to be the one who had that fifth album out that I spent two years on, and then you were tired, so you hurried through your review. If you have any sort of position of authority with somebody else's art, let's try to be cognizant of that. If you're gonna put music together, it's just like, yeah, you want to do right by the music.

Watching Papa Roach Play Basketball (2002)

https://youtube.com/watch?v=b7WD3gD-rec

You went from the fanzine world to some major publications -- but as a sportswriter, covering basketball for a few different magazines. And one of the more unusual games you had to watch was a Jim Beam sponsored Papa Roach pickup game.

SCHARPLING: Yeah! That was a great way spend the day: going to Chelsea Piers in Manhattan, which is this enormous activity center, I guess you'd call it. They have tennis courts and basketball courts -- they have everything there. And the people over at Jim Beam decided that we're gonna have some contest winners play the the four members of Papa Roach in a full-court basketball game. And no one could play basketball, so they went and got a Harlem Globetrotter for each team to try to balance out the play and kind of elevate it. And it was a giant mess. Nobody could play in these four guys, and the Harlem Globetrotters were there just smiling through the worst basketball they've ever played in their lives.

It sounds almost like the kind of thing you and Jon would make up. It has kind of like a Mother 13 vibe to it.

SCHARPLING: Oh yeah absolutely, the best part of those things is when you're in a moment, and you're like, this is... we couldn't make this up, and it's actually happening in the real world. It's just those special moments where you're like, this is surreal. This is like a dream state almost that things are this weird and are happening in real life.

That was right around the time where Napster was kind of throwing the industry into disarray, and it almost feels like the waning days of a certain kind of corporate rock. Where the business just seems to have this air of oblivious ridiculousness around it, pushing this sort of post-TRL brand of "active rock."

If you think about it, it's like, the Nirvana thing crashed and then it was just it turned into this. Nu-metal is ultimately where it ended up. Five years later, it's all nu-metal and it's kind of the end of rock music in a lot of ways. I really I think there's a generation of kids that thought that rock music was Limp Bizkit and Papa Roach and Powerman 5000 and were just "no, I don't like rock music, because that's what rock music is." It's like no, there's other stuff. This is just literally the worst iteration of it maybe ever.

GG Allin (He Passed On, You Know) (2011)

There are a lot of great running gags on Best Show about some particular musicians. I'm not sure how interested you are in talking about GG Allin ... he almost became a character sort of orbiting the show, or at least like a reference. Eventually that resulted in a WFMU pledge drive premium that was a 7" single, Rated GG, where some notable artists (including Ty Segall, the Mountain Goats, and Ben Gibbard) played cleaned-up versions of his songs. How'd that all come together?

SCHARPLING: Oh, I just had the idea and started pulling it together and got people to give tracks, and because people understood that we were like, basically neutering GG Allin with it. It's not some tribute to him. It's just taking his music and making this dumb monster sound dumb. So we were not celebrating him. Early on, the guy wrote good songs, and then he just became a hurtful piece of trash. I feel like that was the intent behind it, to really kind of dismantle the legend of this guy which was growing and growing at that point...not so much lately. I don't know what happened to the GG thing. I don't know if people have the same reverence for him that they were starting to develop. It's funny, the idea of like, the dangerous person like that. I mean, the guy was a total coward in so many ways, and was just a dipshit.

This was one of my formative hang-ups in high school, this sort of subcultural interest or counterculture drive to be transgressive that led to stuff like collecting serial killer paraphernalia or the early internet rotten.com kind of fascination with the grotesque -- and right in the middle of the '90s, where it feels like there's not a lot to worry about and we're all supposed to be happy. It seems like a kind of casual cruelty that I really hope is kind of on the way out.

SCHARPLING: The whole transgressive thing served a purpose because it's pushing back against a certain sort of stodginess, and you want to just shock the previous generation. I mean, I don't think that stuff should ever go away. The idea of scaring the shit out of the old people is a necessary thing that I hope always happens. But that one in particular that does any kind of glorification of serial killers and shit like that... it never sat right with me. I was thought it was just so lame. People collecting John Wayne Gacy paintings and things like that. It's just like, what a waste of time.

There are more sincere tributes the show's brought into the world, though. What are some of the other ones you think really define The Best Show as far a getting bands to do unusual things?

SCHARPLING: We did an album which was the Paul and Linda McCartney album Ram, where we did a track-by-track kind of tribute album and got a lot of people to contribute to that, like Aimee Mann and Death Cab For Cutie and the Black Hollies and Spider Bags, it was just so great. Dump did "Uncle Albert/Admiral Halsey." And yeah, just stuff like that. The force of the community made it that we could pull these things off. It was really pretty exciting to build things that actually would exist then, and it was amazing the way stuff came together. And thankfully, I don't have to do that stuff anymore, because the show is now listener-sponsored. We do a Patreon now and people support it through that. And we don't have to do fundraising marathons and stuff like that, which were truly backbreaking to me. So while the show now might not have certain things that it had on a traditional radio station, I think we make up for it in other spots, too. We just have more control over stuff. We can do what we want with the show, and we could do the show whenever we want. And yeah, there's just a trade off. And I'm kind of I'm happy with the trade off.

Steven Universe (2013)

You mention in your book that Rebecca Sugar had you in mind already for the role of Greg Universe, so it's kind of an interesting case of you finally getting to be a rock star of sorts.

SCHARPLING: Yeah. A very roundabout way, I got to fulfill it all... I got to sing over and over and do so many songs. That was just like a gift I could never have conceived of, to have somebody just give me a part for a thing that they wrote with me in mind, and then kind of cater it to me... that's like the greatest gift you could get. And I got it. Especially for a show that was so cool and funny and meant so much to so many, and still means so much, to so many kids. And adults! I couldn't in a million years, I couldn't predict anything like that ever happening. And it did happen. I guess it's because I do this radio show and I do it the way I want to do it, and I try to put my authentic self out there and hopefully people respond to it. And I'm very fortunate to have had opportunities like that just kind of show up. It's just a testament to just doing your thing in the realest sense possible.

It Never Ends: A Memoir With Nice Memories! is out 7/6 via Abrams. Order it here.