- Sympathy For The Record Industry

- 2001

Let's start, as White Blood Cells does, with "Dead Leaves And The Dirty Ground." I mean, holy shit. Recorded sound does not get much better.

The White Stripes' appeal hinged on the tension between raw spontaneity and meticulous presentation. With the first song on their breakout album, they nailed that balance. On one hand, "Dead Leaves And The Dirty Ground" is some of the smartest, most economical songwriting you'll ever hear. Every structural detail is expertly planned out, from a pogo-ing intro riff that channels John Lee Hooker by way of "Brain Stew" to the way the last line of each verse repeats. Mirroring the music's powerful concision, Jack White's lyrics say so much with so little: "Dead leaves and the dirty ground when I know you're not around/ Shiny tops and soda pops when I hear your lips make a sound." It's a love song that comes at you from bizarre angles, each line inspired and just slightly off-kilter. "If you can hear a piano fall, you can hear me coming down the hall" -- that's a short story, a painting, and a Looney Tunes sound effect all in one sentence.

Yet for all its brilliant craftsmanship, "Dead Leaves And The Dirty Ground" was never guaranteed to be one of the greatest album openers of all time. Just listen to the early live version recorded at Detroit's WDET in 1999, as captured in the fourth episode of Third Man's White Stripes history podcast Striped. The song as we know it is already fully formed, but the dynamics just aren't there. The version White captured at Easley-McCain Recording in Memphis two years later, though? Explosive. Just the sickest thing you can possibly imagine. Meg bashes the bejesus out of her drums. Every power chord is a mortar going off. The peel of feedback that breaks in just before the two-minute mark, as the song rockets to a peak of tension before ripping open into thunderous release -- no amount of thoughtful preparation is a substitute for so much spine-tingling energy.

Everything came together for the White Stripes in that recording. By the time White Blood Cells dropped 20 years ago this week, everything was coming together for them in general. With 1999's self-titled debut, they'd made themselves stars within an insular garage-punk universe, "a nation of twenty-something kids with Dead Moon tattoos and too many black bracelets." The following year, their prodigious sophomore LP De Stijl spread their gospel further across the underground. By 2001, no scene could hope to contain them.

In the beginning the White Stripes had consciously entered themselves into Detroit's lineage of noise-bombed rock 'n' roll, a continuum of feral howlers stretching from the Stooges and MC5 to the Gories and Detroit Cobras. They might have been happy to remain in that world forever, but their twist on the ragged Motor City tradition was too compelling for the rest of the world to ignore. Jack and Meg built up a mythos -- adhering to a strict red-and-white dress code, pretending to be brother and sister -- and a small but potent catalog, culled from the rough 'n' tumble corners of British and American music history. Their sound was deeply familiar but utterly peculiar. And just when nostalgia and backlash against garish late '90s trends opened up a window for back-to-basics rock bands to become real-deal superstars, they put out the strongest front-to-back statement of their career. White Blood Cells catapulted the White Stripes from the dive bar circuit into superstardom. By the end of the following year, they had appeared on the cover of Spin, accepted an MTV Video Music Award from the Olsen twins, and toured arenas with the Rolling Stones.

It's easy to look back on the hype surrounding the retro rock revolution and laugh -- and the idea that these kids in Converse were here to rescue rock 'n' roll from Fred Durst's clutches is admittedly silly. But in hindsight, getting excited about the best of these bands made perfect sense. The Hives, if one-dimensional, were a total powerhouse. The Strokes, if derivative, were pop-songwriter geniuses with the kind of swagger you can't teach. And listening through White Blood Cells is a reminder that the White Stripes were so much more than gimmick and persona. The album is a staggering outpouring of creativity, a reminder of how stridently unique a mishmash of uber-authentic influences can be. The sense that you're witnessing a Mojo editor's wet dream is quickly overshadowed by all the fun you're having. These songs are catchy as hell. They rock. Sometimes they hoot and holler too.

All those dusty blues, country, and garage rock records informing the White Stripes' ethos had been filtered through Jack White's twisted imagination, yet even his wildest ideas were grounded in Meg White's less-is-more simplicity. And really, both of them were about serving the song above all else. Underneath all the idiosyncrasies, White Blood Cells is a pop record that at times rocks extremely hard. For all the volatility animating these songs, melody rules all. Even the hooks Jack stuffed away at the end of the album are stunners, from "I thought you made up your mi-i-ind!" on the scathing rocker "I Can't Wait" to "You thought you heard a sound!" on the haunting piano-led closer "This Protector." The noise Jack wrangled from his guitar tended to imprint itself on your brain, too, as if he couldn't separate his most fiery impulses from his pop pedrigree. And for two people who had fallen out of sync, romantically speaking, he and Meg sure had a telepathic ability to pivot from quiet to loud and back.

"Dead Leaves And The Dirty Ground" was a transcendent example of this chemistry in action, but White Blood Cells covered so much ground beyond that initial blast. The album's other singles -- the unhinged hootenanny "Hotel Yorba," the rampaging punk-rocker "Fell In Love With A Girl," the precious twee fantasy "We're Going To Be Friends" -- were proof of how many ways Jack could write about being smitten. And he had much more than infatuation on his mind back then. A wordless hard-rock anthem called "Aluminum"? Yes, definitely. A discordant Citizen Kane homage about how love does not exist? Absolutely. He's the same boy you've always known, but he's finding it harder to be a gentleman every day. He thinks he smells a rat. You send him to Toledo. (Toledo? Toledo!)

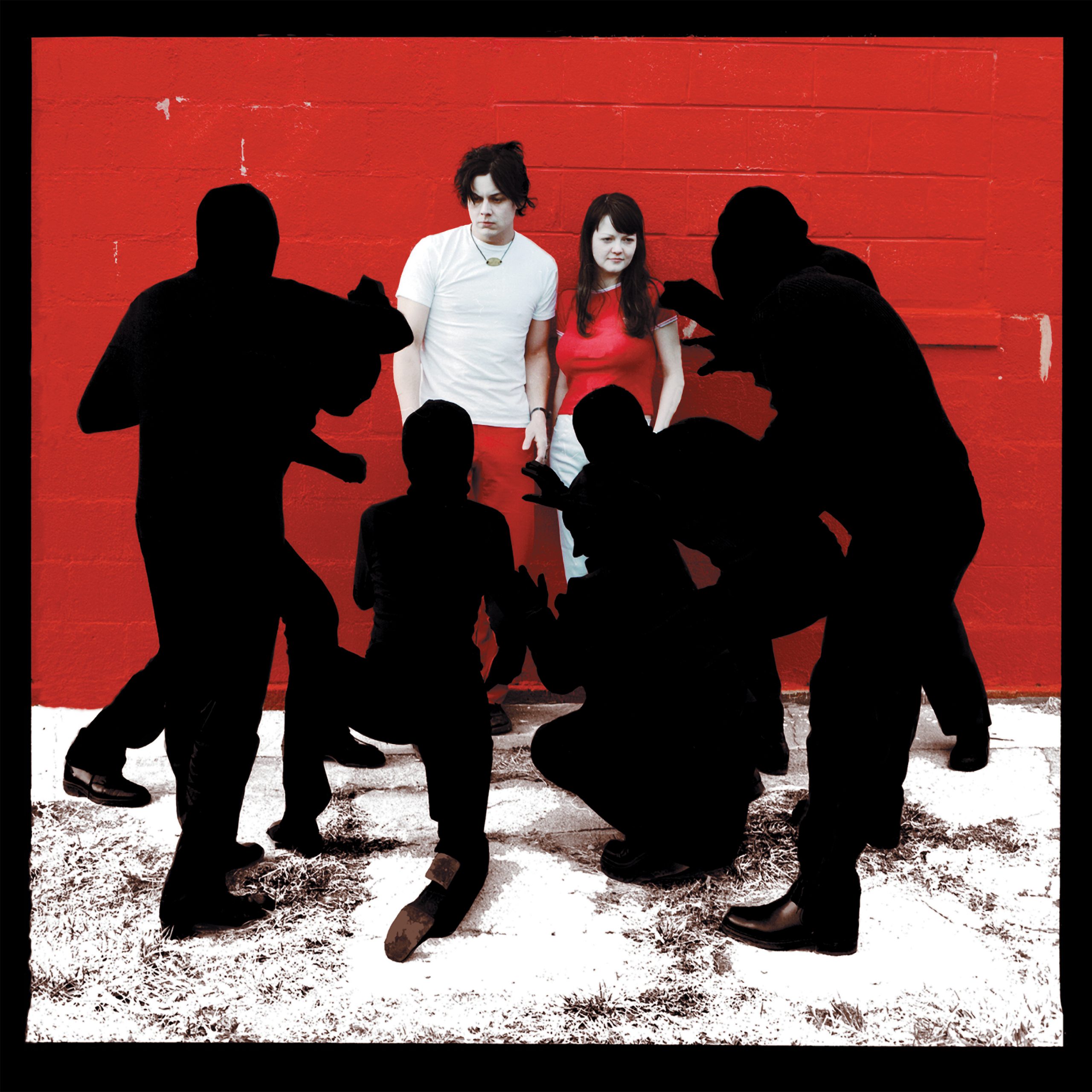

These sidelong sentiments were threaded into many kinds of rock music -- tunes that, despite their throwback feel, were nearly as inventive as the Lego-animated Michel Gondry music video that got the band on TV. The same artisanal touch Jack brought to his upholstery day job played out in songs that shared a sensibility but never a mold. This had been the White Stripes' M.O. since they started, and it reached its apotheosis in the winter of 2001. In just four days of harried recording, before this batch of songs could calcify into rote muscle memory, Jack and Meg wrangled their inspiration and nervous energy into a tour de force. Clearly they had some inkling that they'd captured something intoxicating because both the cover art and the album title hinted at an influx of unwelcome attention. Still, some part of them relished the prospect of expanding their empire beyond the confines of the dingy rock 'n' roll subculture that raised them, or else they would have ended the band for good before it had a chance to make them famous. This stuff was really good; they were gonna need a bigger room.