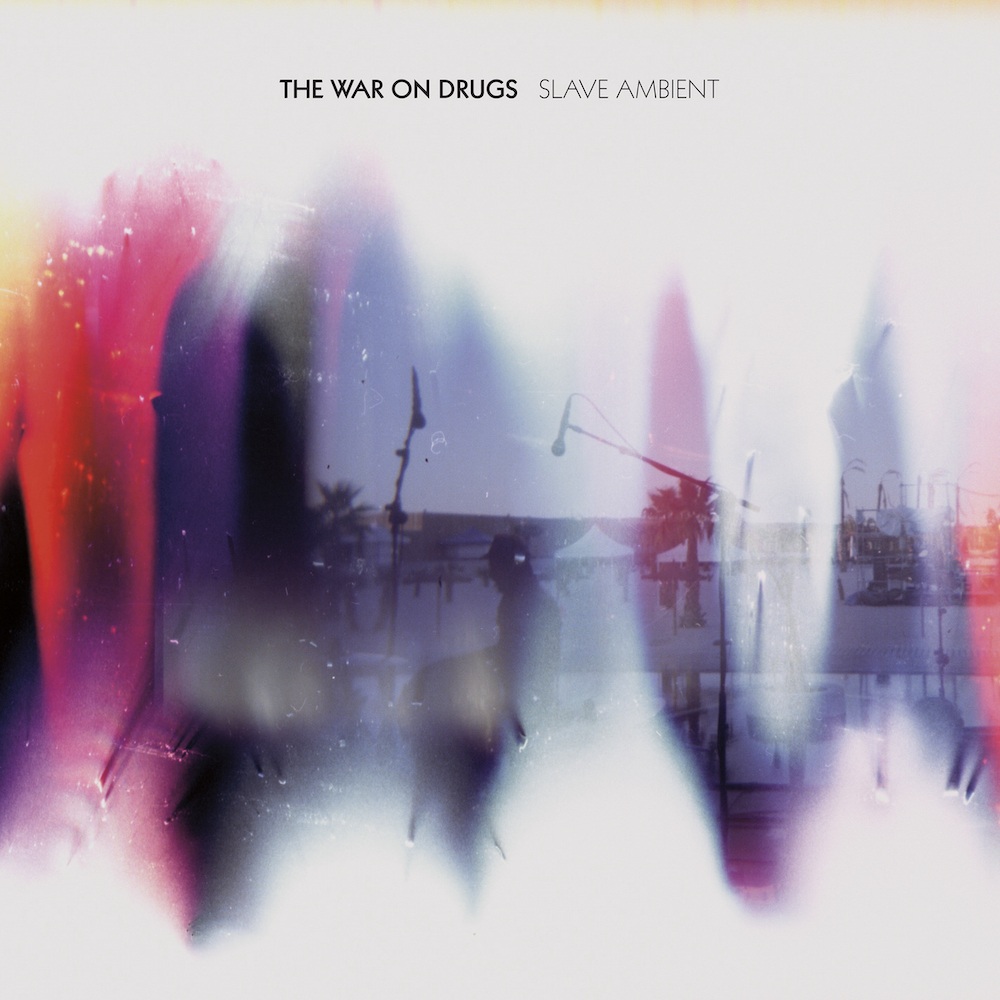

- Secretly Canadian

- 2011

In 2011, the War On Drugs were just getting started. Technically, the band had already been around for over half a decade, and in 2008 they’d released a well-liked debut called Wagonwheel Blues, an album that combined classic rock-isms with a hissing, ramshackle 21st century psychedelia. Back then, Kurt Vile was in the band, and Adam Granduciel wasn’t yet quite known as the visionary architect of the Drugs. Even by the time Vile had departed and Slave Ambient came out, Granduciel’s work lived in the shadow of his friend and former bandmate. Philadelphia was just bubbling up as a topic in the modern indie rock conversation, and Vile was already an acclaimed songwriter. In almost every interview Granduciel gave for Slave Ambient, he had to talk about Vile, and about how they were still friends, and about how he in fact toured with the Violators and that partially accounted for the three year gap between the Drugs’ debut and its followup.

That context now, obviously, seems quaint. Granduciel and Vile were both operating on a different wavelength relative to what seemed the forefront at indie in that moment, despite the fact that many DIY bands would rise out of Philly in the coming years as cultural hubs like New York became prohibitively expensive. But can you imagine? A time when Vile was viewed so loftily and Granduciel was that other guy? The conversation has long since shifted, and the War On Drugs’ ascension has long since been underway. When they released Slave Ambient 10 years ago today, nobody could have really seen all that coming -- but it was the beginning.

Wagonwheel Blues had already garnered the Drugs some positive coverage. It was full of songs that yipped and howled and barreled within a sort of static-laced haze. Even now, with all we know about what the Drugs would become, you can see it as a dry run, the way Granduciel took familiar forms and warped them through his own filter. Slave Ambient took all that and pushed it further, made it more vivid and realized.

At the time, Slave Ambient was an oddity. We were only a couple years into indie bands anointing Bruce Springsteen a hip and pervasive influence, and just about any piece of writing on the War On Drugs marveled at Granduciel's obvious songwriting heroes -- Bruce, Dylan, Petty -- being put through the funhouse mirror of textures and drones and layers of ambient synths. And it was a novel sound. If you were predisposed to rock’s historical touchstones, Slave Ambient was a marvel: a guy off to there to the side, not particularly bothered by or interested in any contemporary trends, writing churning highway rockers and singing in clipped percussive Springsteen cadences and Dylan sneer alike, but blanketing it all in an otherworldly sheen that, somehow, made ancient history feel alive. You could listen to Adam Granduciel, and you could hear the past and present transforming into something new.

That was only hinted at on Wagonwheel Blues. Then Slave Ambient was coaxed into being from a whole collection of songs ideas, yes, but also loops and ambient snippets. Sometimes Granduciel would just start there, in the ether, finding a particular drone he liked and then figuring out a song on top of it. He walked the streets of Philadelphia, listening to it all on repeat, waiting for the music to call out to him. In the end, him taking the time to search yielded an album fascinating in its polarities. Especially in its segue-laden second half, Slave Ambient can be a heady zone-out listen. At the same time, the songs were immediate and punchy. Granduciel’s songwriting has evolved since then, and has had no shortage of big, hooky moments. If you go back to Slave Ambient, though, it still has some of his clearest singing and most direct melodies.

For an album with 12 tracks and only eight "full songs," there never felt like there was a wasted moment on Slave Ambient. Hallucinogenic passages carried you from banger to banger, from the easygoing glisten of "Brothers" to the motorik whoosh of "Your Love Is Calling My Name," from the propulsive "Baby Missiles" to the centerpiece of "Come To The City." The latter still stands as a career highlight. Right there in the middle of Slave Ambient, you have everything that makes Granduciel a special songwriter. From the dramatic atmospheric build of "The Animator," "Come To The City" eventually comes into view -- first as mirage, then as something more tangible the more its locomotive drumbeat rises to the fore. In the context of the album, the song is sort of like one long series of climaxes -- the verses already a payoff emerging from the murk of "The Animator," the way they bloom into the "Woohoo!" and guitar break of the chorus-as-such, and finally Granduciel's refrain at the end, getting swallowed back up by all the noise.

It was a dense, lush sound, one in which you could always find new details but also one where the songs crystallized enough to pull you in right away.For me, the first time I heard Slave Ambient was one of the most random places possible. I had been studying abroad in Shanghai for a few months, and my brother -- who had just seen the War On Drugs open for the National in New York -- sent me a few YouTube links to check out. Thanks to a VPN we had installed to bypass Chinese firewalls, it was damn near impossible to load YouTubes, but when I finally heard these songs, I was floored. Maybe a month later, I tracked down a CD copy of Slave Ambient in Sydney, and probably paid something like 25 American dollars for it. (I was a stubbornly late abandoner of physical media.) For almost a week, I walked every inch of Sydney listening to this album, staring at Christmas decorations in the summer and oceans that were such an alien shade of blue they almost seemed psychedelic themselves. I was immersed in this sound, somehow a perfect soundtrack for ambling around a place as foreign and far-flung to me as Australia. But all along the way, Slave Ambient was really beckoning me back home.

For a young classic rocker, the War On Drugs were already easy to love. But for me, having grown up in small-town Pennsyvlania about 90 minutes north of Granduciel's home in Philly, their sound felt like mine. In their music, I heard every train graveyard, every dead shopping mall, every collapsing coal breaker, every formerly opulent stone building left to decay in towns long since left behind. Many of Granduciel's lyrics on Slave Ambient are little folk echoes, almost placeholders -- rollin' and driftin', looking out past the rubble. He's "been up in the highlands, past the farms and debris." And in all that wreckage, he found something still living, enough that he could breathe a whole different array of colors into it. Driving around Pennsylvania listening to Slave Ambient, the fact that Granduciel could move through those same surroundings and find something new to be pulled up from the ground was more than enough to make you a fan -- it was inspiring.

It felt like I knew the sound of Slave Ambient somewhere deep down, but at the same time Granduciel articulated it in a way I could've never imagined myself. Each time a grainy acoustic guitar ran up against a mutating loop, or his earthen voice sang above celestial synths, you could see the past and present and whatever came next mingling freely, a vibrant dream cohering where they all met.

Of course, that's long since become the calling card for the War On Drugs. Throughout, they have been described as classicist musicians tweaking not-exactly-enamored corners of rock history. When Slave Ambient's successor Lost In The Dream arrived in 2014, Granduciel built on where he'd been before but also crafted a whole new sound. More washed-out and bleary, at times more organic, but still existing in a Technicolor mist only he could see. And if people had tripped over themselves catching all the Springsteen and Dylan DNA on Slave Ambient, the next iteration of the Drugs really sent them reeling. Don Henley? Dire Straits? That whole stretch of years where Boomer musicians tried to keep up with the times, writing dusty rockers dappled with synthesizers? Really?

It was one of the least excavated parts of music history even in a time addled with nostalgic cycles and recurring resurrections. That has remained the path Granduciel has walked since, but at the same time there was always an undercurrent that felt, even as the band garnered runaway acclaim, uncharitable in drawing those comparison points. Granduciel was never exhuming corpses in another revival. From Lost In The Dream onwards, he took the Drugs into a space both watercolor and chiaroscuro, manipulating history to his own liking more than ever before.

And, bizarrely, it brought him greater and greater success. From the very first time we all heard the "Woo!" in "Red Eyes," we knew we were in for something different musically on Lost In The Dream. What was impossible to predict, even then, was the implausible skyrocketing rise of this band -- matter-of-fact Philly guys playing in a working-class rock tradition turned cosmic, steadily climbing up festival posters until they were Grammy winners and one of the only big new rock bands in an era when big new rock bands are… not often a thing. In the wake of Lost In The Dream's true breakthrough, Granduciel signed a two-record deal with Atlantic. The second of those, I Don’t Live Here Anymore, comes out in October -- and if the absolute bangers Granduciel previewed on Instagram last year are anything to go by, it may take the War On Drugs ever further into the stratosphere.

For years, I used to hang on Slave Ambient, this gorgeous and transfixing document of when I first found this new strange sound from this scrappy Philadelphia band. I used to hold it up alongside the much more towering records that followed. But now, revisiting it on the other side of all that, you do have to yield a bit, admit that as wholly unique as Slave Ambient was in its time, it now doesn't quite compare to the peaks Granduciel has scaled since. It's more elusive, more straight-up druggy, without the precise yet blurred balance Granduciel has struck between sharp songcraft and madman sonic wizardry on the subsequent two albums. All these years later, it almost feels more appropriate to group Slave Ambient alongside Wagonwheel Blues as the prologue, the build-up to the War On Drugs becoming what they were supposed to be. It's still a rich, entrancing prologue, but a prologue all the same. Eventually, out past the rubble and up from the waves of ambience, a "Woo!" would ring out, and there would be no looking back.