November 25, 1989

- STAYED AT #1:2 Weeks

In The Number Ones, I'm reviewing every single #1 single in the history of the Billboard Hot 100, starting with the chart's beginning, in 1958, and working my way up into the present.

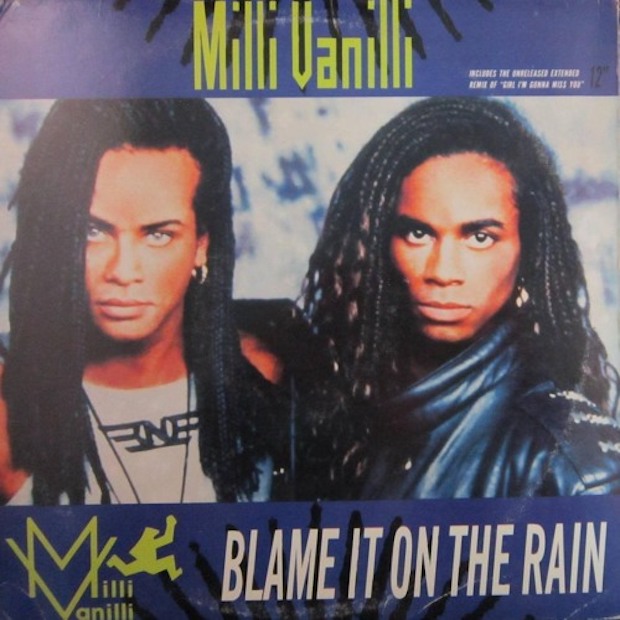

When the whole Milli Vanilli enterprise fell apart, the music business really only had itself to blame. In the months before the grand revelation of the Milli Vanilli deception, the German producer Frank Farian's project seemed to be one of 1989's great success stories. Girl, You Know It's True, the repackaged version of Milli Vanilli's 1988 European album All Or Nothing, sold six million records. Milli Vanilli also sent three straight singles to #1. "Blame It On The Rain," the final Milli Vanilli #1, was a song built specifically to appeal to American audiences, and like everything else bearing the Milli Vanilli name, it succeeded better than anyone could've predicted. While the backlash surrounding the project swallowed up the lives of Rob Pilatus and Fab Morvan, the two men presented to the world as Milli Vanilli, the songwriter and producer responsible for "Blame It On The Rain" both remained successful for years afterwards.

"Blame It On The Rain" didn't appear on All Or Nothing, the Milli Vanilli album that came out in Europe in 1988. When Clive Davis signed Milli Vanilli to an American deal, he had some demands. Davis, notorious for taking artistic control of his signees, insisted on a couple of new Milli Vanilli tracks for the American release. Davis wanted Milli Vanilli to cover the Isley Brothers' 1969 banger "It's Your Thing," a funk classic that had also been a #2 pop hit. (Clive Davis was very big on covers of old R&B songs. The original "It's Your Thing" is a 10.) And Davis also wanted Milli Vanilli to record a track from Diane Warren, the American songwriter who rode the soft-rock zeitgeist in the late '80s and beyond.

Frank Farian did what Clive Davis wanted, and that Diane Warren song became Milli Vanilli's final #1 hit. That success put Diane Warren on a very short list of songwriters who had replaced themselves at #1. "Blame It On The Rain" was Warren's fourth #1 hit, and it knocked Bad English's "When I See You Smile," another Warren-written song, out of the #1 spot. Even if you don't like the songs in question, it's a pretty impressive achievement to score back-to-back #1 hits with an aging arena-rock supergroup and a duo of lip-syncing, rap-adjacent European club-pop singers. Diane Warren is the only person in history who has pulled that off, and she's probably the only person in history who could.

Diane Warren didn't write "Blame It On The Rain" with Milli Vanilli in mind. In fact, she'd never heard of Milli Vanilli when she wrote it. Instead, Warren wrote the song for the Jets, the Minneapolis family of Tongan-American Mormons who had a run of big hits in the '80s. (The Jets' two highest-charting singles are "Crush On You" and "You Got It All," both from 1986, peaked at #3. Both are 5s.) The Jets turned "Blame It On The Rain" down, so Warren took the song to Clive Davis.

In Fred Bronson's Billboard Book Of Number 1 Hits, Warren tells the story:

I submitted it to Clive Davis. I played the song for him, not knowing he needed songs for Milli Vanilli, because I didn't even know who they were... I would submit a song for somebody big, like Whitney Houston, and he'd say, "I don't want it for Whitney, but I want it for Exposé," or "I want it for Taylor Dayne." And I'd say, "No, no, I want somebody big, I want Whitney." Then these new artists would sell, like, three million copies and have all these hits. I'd kick myself in the head. So when Clive said, "Milli Vanilli," I said, "Yeah, I trust you."

It's usually probably not a great idea to trust Clive Davis, but in this case, it worked out for Diane Warren. In the Bronson book, Warren says that she didn't know anything about Milli Vanilli's faces not being the singers on the record, and she said that she was still proud of the song. The whole thing didn't hurt Warren at all; she'll be in this column many more times.

"Blame It On The Rain" does a lot of the same things as so many other big Diane Warren power ballads. It's grand and sentimental melodrama about lost love, and it's got a massive stick-in-your-head chorus, so it's Warren operating within her own comfort zone. As a songwriter, Diane Warren was never particularly genre-specific, and "Blame It On The Rain" didn't have to be dance-pop. Just as easily, the song probably could've been a hit for washed-up rocker types like Bad English.

As a piece of songwriting, I think "Blame It On The Rain" is more solid than a lot of what Warren was doing at the time. "Blame It On The Rain" comes from the perspective of someone who's broken up with a woman. This person wants her back, but that's not happening, so the song's narrator tries to tell him to blame the rest of the world instead of himself: "Blame it on the rain that was falling, falling/ Blame it on the stars that shine at night/ Whatever you do, don't put the blame on you." That advice has its own kind of logic. It's a flowery way of saying that if you can't change your own fuckup, then you should charge it to the game and keep moving.

Frank Farian produced the Milli Vanilli version of "Blame It On The Rain," using all the same session singers as he'd used on the previous Milli Vanilli records. Farian was a dance-pop producer, not someone who was used to handling ballads. (Milli Vanilli's previous #1 hit, the hacky heartbreak song "Girl I'm Gonna Miss You," stands as proof that Farian was out of his depth there.) "Blame It On The Rain" doesn't have a ton of Farian's Milli Vanilli trademarks. There's no clumsy rap verse, no shuffling breakbeat, no lyrics that have clearly been utterly mangled in translation. In the video, Rob Pilatus, the guy who lip-synced the rap parts, doesn't really have much to do. But Farian pulls off a bunch of tricks to turn what could've been a boringly soppy ballad into something that moves.

In telling the Milli Vanilli story, Frank Farian is quite clearly the villain. He trapped Rob Pilatus and Fab Morvan in goofy contracts, forced them to keep his secret, and refused to let them sing on records, something that they very much wanted to do. But Farian is also the singular creative force behind Milli Vanilli, and as a producer, he knew what he was doing. The best things about "Blame It On The Rain" -- the nifty digital bassline that opens the track, the hugely satisfying timing of that first snare hit -- are all Farian. It was probably also Farian's idea to quote from Eruption's 1978 disco version of "I Can't Stand The Rain," a single that peaked at #18 in the US, on the outro. I like the growly, yelpy soul vocal from John Davis, a Black American session singer who'd served in the military in Germany. If "Blame It On The Rain" isn't the best of Diane Warren's many #1 hits, it's pretty close.

By the time "Blame It On The Rain" topped the Hot 100, the clock was ticking on Milli Vanilli. Even if the world had never learned that Pilatus and Morvan hadn't sung on the album, backlash would've probably swallowed Milli Vanilli before they had time to put out another album. Rolling Stone named Milli Vanilli the worst group and Girl I'm Gonna Miss You the worst album of 1989. Damon and Keenan Ivory Wayans clowned Milli Vanilli hard in an early In Living Color sketch. The novelty of these spasmodically dancing half-rapping European model guys wasn't going to last forever. But Milli Vanilli did squeeze in one more hit: "All Or Nothing," which peaked at #4, in February of 1990. (It's a 6.)

After all of Milli Vanilli's success, Pilatus and Morvan had also come to think of themselves as stars, and that wasn't helping anything. In a Time profile that ran in March of 1990, Pilatus talked a whole lot of shit on his pop-chart elders: "Musically, we are more talented than any Bob Dylan. Musically, we are more talented than Paul McCartney. Mick Jagger, his lines are not clear. He don't know how he should produce a sound. I'm the new modern rock 'n' roll. I'm the new Elvis." Afterwards, Pilatus apologized, claiming he'd been taken out of context: "I was in shock when I read it. I am a fan of Mick Jagger and the Stones. I mean, I knew I wasn’t singing, so why would I ever criticize the Beatles? All I said was that Elvis was a big idol in his time, and we were big in ours."

Milli Vanilli were big in their time, though that time did not last long. In February of 1990, the business officially anointed Milli Vanilli. The group won the Grammy for Best New Artist, beating out a field that included Neneh Cherry, Soul II Soul, the Indigo Girls, and Tone Lōc. Milli Vanilli performed at the ceremony and accepted the award from Kris Kristofferson and Young MC. In his short speech, Morvan said that it was "an award for all artists in the world." It would soon become an award for no artists in the world.

The news was getting out. In December of 1989, session singer Charles Shaw told Newsday that he'd done the real rapping on the Milli Vanilli record. Shortly thereafter, Shaw retracted his claim. Entertainment Weekly later reported that Frank Farian had paid Shaw $150,000 to say that he had not, in fact, been the rapper. Less than a year later, though, Farian went ahead and admitted it himself. Pilatus and Morvan had demanded to sing on the next Milli Vanilli record, and Farian wasn't going to let that happen. Farian blew up his own secret, telling the Associated Press that he had fired Pilatus and Morvan: "Sure, they have a voice, but that's not really what I want to use on my records."

The shitstorm that followed was loud and intense. Pilatus and Morvan gave a press conference. They admitted the truth, apologized, and voluntarily gave up their Grammy. Pilatus told the LA Times, "The last two years of our lives have been a total nightmare. We've had to lie to everybody. We are true singers, but that maniac Frank Farian would never allow us to express ourselves." The Grammys' governing body revoked the Best New Artist award and gave it to nobody; it's still the only time in Grammys history that an award has ever been taken away and left vacant.

Arista claimed that the label had no idea who had really done the vocals. In the liner notes for Girl, You Know It's True, the label had credited those two as the singers. Fans filed class action lawsuits, and in a 1991 settlement, Arista pledged to give a few bucks to anyone who had bought a Milli Vanilli record. Arista immediately deleted the Girl, You Know It's True album and masters from its catalog; despite all the copies it sold, the album remains out of print today. (If you want to listen to Milli Vanilli on streaming services, you can still find the European All Or Nothing album, and there are a couple of Milli Vanilli greatest-hits albums out there -- a truly strange thing for a group that only ever released one LP.)

Frank Farian seemed annoyed and impatient about the whole story. Talking to The Washington Post, he simply explained that this was how things were done: "There's too much uproar now over the whole thing... It was fantastic new music, people were happy, so what's the problem?" Farian explained that Milli Vanilli was never a group; it was simply a "project": "It was two people in the studio, and two people onstage. One part was visual, one part recorded. Such projects are an art form in themselves, and the fans were happy with the music... The fans and the music industry have to get used to this kind of project."

This particular project was done. Farian made another album with the Milli Vanilli session singers, presenting them as "the Real Milli Vanilli." But the Real Milli Vanilli's 1991 album, which had four new Diane Warren songs and the ridiculous title The Moment Of Truth, didn't even come out in the US. Pilatus and Morvan, determined to prove that they could actually sing, moved to LA and released a 1993 album under the name Rob & Fab. The album came out on an indie label, which only bothered to press up a few thousand copies. Nobody wanted to touch these guys.

The downfall of Milli Vanilli was a moment of legitimate crisis for the music business. The press went crazy over the story. The schadenfreude factor was massive, and the music business -- which has perpetuated frauds like Milli Vanilli countless times over the decades, and which was actively running several similar schemes at the same time -- went into mea culpa overdrive. For years afterwards, new and emerging pop singers felt the overriding need to prove that they could sing. General music-business damage control probably had something to do with the rise of melisma-heavy R&B singers in the '90s. Mariah Carey, someone who will appear in this column a great many times, had the perfect timing to come along just as the Milli Vanilli backlash was kicking up, when the record industry needed someone who really could do dazzling things with a microphone. In its own way, then, the Milli Vanilli crisis changed the course of pop music history.

Amidst that whole shitstorm, though, Frank Farian did just fine for himself. Farian spent the '90s putting together a series of Euro-dance groups, and a couple of those groups, La Bouche and Le Click, were pretty successful. (Frank Farian co-produced La Bouche's highest-charting single, 1995's "Be My Lover," which peaked at #6. It's an 8. Le Click's highest-charting single, 1997's "Call Me," peaked at #35.) In the late '90s, Farian, apparently feeling bad about how the whole thing had gone down, agreed to produce a new Milli Vanilli record, with Pilatus and Morvan actually singing. The album never came out.

In the time after the Milli Vanilli revelations, Rob Pilatus spiraled. In 1990, he was charged with sexual assault. A year later, he attempted suicide. In 1996, Pilatus was arrested for beating up a couple of people and breaking into a car, and he was sentenced to three to six months of rehab. While working on that comeback album with Farian, Pilatus was found dead in a Frankfurt hotel room. He'd overdosed on a combination of drugs and alcohol. He was 32.

Shortly after Pilatus' death, VH1 aired the premiere episode of Behind The Music, which was dedicated to the whole sordid and fascinating Milli Vanilli saga. Morvan went on to work as a motivational speaker and, for a little while, a radio DJ in LA. He released a 2003 solo album. In 2015, Morvan and Milli Vanilli session singer John Davis announced that they were teaming up to form a duo called Face Meets Voice. The video of them performing together on German TV is both deeply strange and slightly moving. Earlier this year, John Davis died of COVID-19. He was 66.

Rob Pilatus and Fab Morvan got a raw deal from the music business. So did John Davis and the other people who sang on the Milli Vanilli records. Clive Davis and Frank Farian and various other higher-ups got richer. That's how this shit always seems to go. In recent years, there's been talk of a Milli Vanilli biopic in development. I'd love to see that movie, but it will probably be pretty depressing. Milli Vanilli won't appear in this column again, but they'll cast a shadow over it for a while.

GRADE: 7/10

BONUS BEATS: On his Randy Jackson-produced 2006 album Overnight Sensational, the soul legend Sam Moore inexplicably covered "Blame It On The Rain," and he enlisted the help of American Idol winner Fantasia. Here's Moore's version:

(Sam Moore was half of Sam & Dave, whose highest-charting single, 1967's "Soul Man," peaked at #2. It's a 9. Fantasia will eventually appear in this column.)