- Columbia

- 2001

"I contain multitudes," Bob Dylan proclaimed at the start of his 2020 album Rough And Rowdy Ways. It's a line that virtually only he and the poet he borrowed it from -- Walt Whitman -- could get away with. Who's going to argue with Bob? At this point, his body of work is nothing short of monumental, an incomparably rich and wide-ranging oeuvre that defies categorization. Of course, had the Dylan saga come to an end with the 20th century, his legacy would have been secure. But miraculously, the last two decades have seen the songwriter restless and energized, and he's added considerably to his already well-stuffed canon.

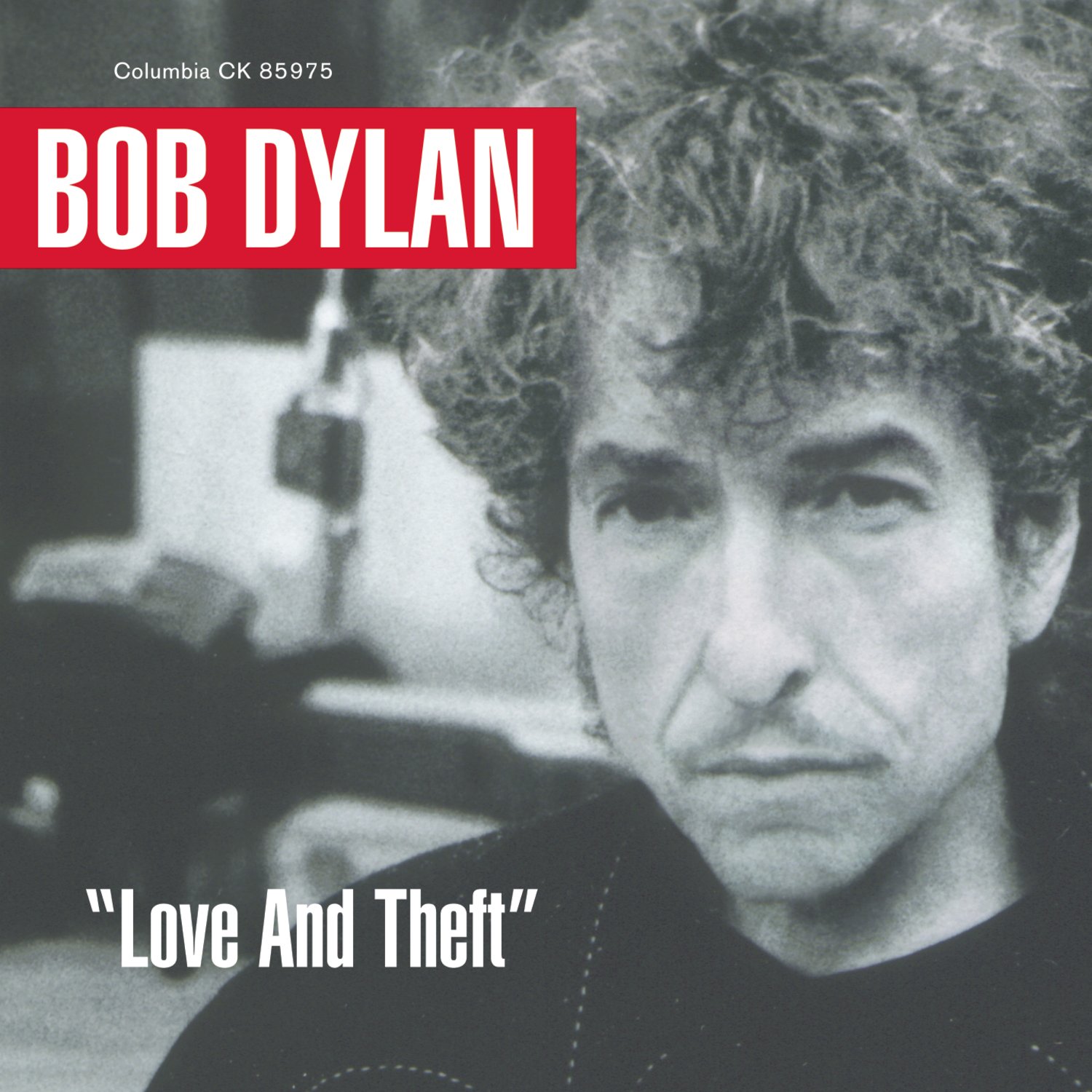

"Love And Theft", released 20 years ago this week, served as his powerful opening statement in the 21st century, and the LP gave him the momentum needed to continue to bewitch and bewilder listeners through the present day. Like Dylan himself, "Love And Theft" contains multitudes. Here are just a few ways to dive into this kaleidoscopic late-era masterpiece.

"Love And Theft" is a 9/11 record.

Let’s get this one out of the way first. "Love And Theft" was released on Sept. 11, 2001 -- and for many, the album is inextricably linked with that terrible day. At the time, several lines stood out as eerily prophetic: "Sky full of fire, pain pouring down" in "Mississippi"; "Today has been a sad ol' lonesome day" in "Lonesome Day Blues"; "High water risin', six inches ’bove my head/ Coffins droppin' in the street / Like balloons made out of lead," in "High Water (For Charley Patton)." These are all after-the-fact connections, of course, tragic relevance through coincidence. But that ominous feeling is hard to shake.

From the very beginning, Dylan has had a strong apocalyptic streak, a predilection for end-times imagery and an eye for biblical catastrophe -- and his work resonates during troubled times because of it. But he has often strived to distance his doom-laden songs from historical specificity, preferring something more timeless. In a 1963 interview with Studs Terkel, Dylan tried to steer his interviewer away from tying "A Hard Rain’s A-Gonna Fall" to the Cuban Missile Crisis. "It's not atomic rain, it's just a hard rain," he insisted. "It's not the fallout rain, it isn't that at all. I just mean some sort of end that's just gotta happen."

In the weeks following 9/11, Dylan was similarly cagey when Rolling Stone's Mikal Gilmore told him that "Love And Theft" "matches the spirit of dread and uncertainty of our present conditions." After quoting Kipling ("God help us, for we knew the worst too young!"), the songwriter admitted that "the rational mind's way of thinking wouldn't really explain what's happened." His only advice? "People will have to change their internal world." It’s the opposite of an easy answer or a thoughtless platitude, and, like much of "Love And Theft" itself, it still rings true -- perhaps now more than ever.

"Love And Theft" is a comedy record.

Looked at from a completely different angle, "Love And Theft" stands as one of Dylan’s downright funniest efforts, its lyrics packed with playful puns, goofy old minstrel routines, and irreverent wordplay. Comedy has long been a part of the man's schtick; during his earliest coffeehouse days, Dylan's Chaplin-esque timing, impish sense of humor, and often surreal talking blues songs always lightened the mood amidst his heavier material. His hallowed trio of mid-sixties electric records blazed with a razor-sharp wit worthy of Lenny Bruce, and his interviews and press conferences from this period were masterclasses in comedic misdirection. The Basement Tapes, meanwhile, were often hilarious, with Bob regularly cracking himself and his Band-mates up mid-song.

While that spark was less prevalent in the years that followed (though the songwriter was still known to crack a few groan-inducing dad jokes onstage), "Love And Theft" heralded the return of Bob Dylan, the grinning trickster. Written around the time of the Bush v. Gore presidential election, opener "Tweedle Dee & Tweedle Dum" felt like a cutting satire of the US's increasingly moronic political pageantry. "High Water," which many associated with 9/11, featured the then-60-year-old Bob urging: "Jump into the wagon, love, throw your panties overboard." "Summer Days" is a riotous litany of swaggering boasts and one-liners set to an relentlessly swinging beat. There's even a knock-knock joke on "Po' Boy": "Knockin' on the door, I say, 'Who is it and where are you from?' Man says, 'Freddy!' I say, 'Freddy who?' He says, 'Freddy or not here I come!'"

Dylan likely didn’t mean for the album's comical side to keep his listeners in stitches, per se. The effect of the humor that runs throughout the album's 12 songs is to create a uniquely American landscape, one populated by a rogue's gallery of hucksters, conmen, and bullshit artists. Unreliable narrators wearing any number of masks, hiding behind inscrutable riddles and rhymes. There's danger behind every punchline. You may be laughing now, Dylan warns, but you're just as likely to be crying later.

"Love And Theft" is a comeback record.

"You can always come back, but you can’t come back all the way," Dylan sings at the end of "Mississippi" -- and you can't help but hear the line as a sly dig at the innumerable critics and fans who had written him off at various points over the years. By the dawn of the 20th century, Dylan had "come back" countless times, beloved one year, derided the next in a seemingly never-ending cycle. In 2001, he was still riding the wave of his most recent comeback, the Grammy Album Of The Year-winning Time Out Of Mind, which was a massive critical and (relatively) popular success. It might've made more sense for Dylan to blow that goodwill on the next go-round, as he did with 1990's Under The Red Sky (the much-maligned follow-up to Oh Mercy) or 1985's Empire Burlesque (the even-more-maligned follow-up to Infidels).

"Love And Theft" flipped the script; it's a comeback-from-the-comeback record. Judging from various interviews around the time of the LP's release, one got the sense that Dylan had been irritated by how Time Out Of Mind had been interpreted by some as a grand statement on aging and mortality, focusing in on a few songs ("Not Dark Yet" in particular) and Daniel Lanois' ghostly production. With his next effort, Dylan was determined to show that he, himself, was not a ghost -- not even close.

Taking on the producer mantle under the alias Jack Frost, Dylan eschewed the reverberant murk of TOOM, replacing it with something much crisper, his vocals clear and up-front in the mix, his backing band steady and confident. As a result, "Love And Theft" is one of Bob's most satisfying records, with a sound that ideally complements the songs. It's an approach that he's kept more or less in place ever since, giving the last two decades of his work an overall cohesiveness that was lacking throughout his career. "Love And Theft" provided a template. Afterwards, Dylan didn’t need to make any more comebacks.

"Love And Theft" is a band record.

No, not a record by the Band, Dylan's erstwhile collaborators. Rather, "Love And Theft" is a record by the Bob Dylan Band -- guitarists Larry Campbell and Charlie Sexton, bassist Tony Garnier, drummer David Kemper, and organist Augie Meyers. With the exception of Meyers, this group had been serving on Dylan's so-called Never Ending Tour for several years, growing into a strong unit that could expertly reinterpret the catalog while still remaining true to it. "When our band was kicking on all cylinders, it was pretty hard to beat," Campbell later said. "I got to say there was good chemistry there."

For a good example of that chemistry, check out this fan-favorite late-2000 show in Portsmouth, England, a few months before Dylan and the Campbell-Sexton lineup recorded "Love And Theft". It's virtuosic roots rock from start to finish, moving comfortably from the gospel-grass close harmonies of the opening "Hallelujah, I'm Ready To Go" to the buoyant country funk of "Country Pie," from the smoky, jazz-inflected re-imagining of "Trying To Get To Heaven" to a barnstorming hard-rock "Drifter's Escape." These were musicians who had decades (centuries?) of American music at their fingertips, and Dylan was invigorated by them, delivering some of his finest, most focused vocals of the era.

Since the mid-'80s, Dylan had rarely brought his touring bands into the studio, usually preferring a revolving door of session players. Luckily, this time around he realized that his current group would be more than capable of bringing his newest songs to life. They delivered on that promise -- and then some. Though their leader is obviously centerstage throughout, the band is one of this record's main attractions, laying down a crackling backing that at various moments harkens back to Tin Pan Alley, vintage Chicago blues, classic country, Sun Records rockabilly, and a host of other genres.

However, "Love And Theft" never feels like an exercise in nostalgia, thanks to that all-important chemistry Campbell mentioned. By the time the album was finished, Dylan knew he and his cohorts had succeeded in crafting something timeless. "It'd be as good tomorrow as it is today and would've been as good yesterday," he proudly told Gilmore. "That's what I was trying to make happen."

"Love And Theft" is a Burroughsian record.

It’s been a bit of a parlor game amongst fans and scholars to trace the sources of Dylan's lyrics, which have allegedly drawn from such disparate wells as Star Trek reruns, obscure Japanese biographies, and Civil War-era poetry. When called out on it, Dylan got irate. "Wussies and pussies complain about that stuff," he said in a 2012 Rolling Stone interview. "In folk and jazz, quotation is a rich and enriching tradition. It's true for everybody but me. There are different rules for me."

But could Dylan’s borrowings (which extend to his paintings, his memoir, and even his Nobel Prize acceptance speech) amount to more than just an evocative assemblage of bric-a-brac from days gone by? The songwriter has long been aware of William Burroughs' so-called "cut-up" and "fold-in" techniques, wherein the author randomly rearranged his and others' words into new forms. Burroughs insisted that by doing so he could uncover hidden truths, subliminal messages, uncanny synchronicities. Was Dylan up to something similar on "Love And Theft" and his subsequent 21st century records?

It’s hard not to feel a little bit like a conspiracy theorist when you wade into this end of the Dylanologist pool; infamous nutjob A.J. Weberman was convinced that there were all kinds of codes lurking within Dylan’s lyrics -- to the extent that he started going through the songwriter's trash. But then you read the work of Scott Warmuth, which picks apart a dizzying number of "puzzles, jokes, secret messages, secondary meanings, and bizarre subtexts" in Dylan's art, and a clearer, if not conclusive, picture begins to develop. Warmuth's deep dives into "Tweedle Dee & Tweedle Dum" are particularly convincing, revealing layer upon layer of lyrical and musical allusions, ranging from an otherwise unremarkable New Orleans travel guide to Johnnie and Jack's "Uncle John's Bongos," from the Grateful Dead to Edgar Allen Poe. There’s a song beneath the song here, Warmuth suggests -- if you know where to look.

To what end is Dylan playing these strange games in his music? Is it just to amuse himself? To confuse his fans? To achieve some kind of occult effect a la Burroughs? It's hard to say -- and Dylan wouldn't tell you if you asked him. "I'd like to interview people who died leaving a great unsolved mess behind, who left people for ages to do nothing but speculate," Bob once said. Maybe the mystery is the point of it all.

"Love And Theft" is a perfect Bob Dylan record.

If Dylan's ongoing Bootleg Series (Vol. 16 drops next week) has proven anything, it's that his albums usually tell only part of the story; there are almost always fascinating outtakes and alternates to contend with. To date, however, no further "Love And Theft" material has surfaced, officially or unofficially. As with any of his songs, the album mutated onstage: "High Water" transformed into a heavy rock number; "Summer Days" got a square-dance flavor at some point; on his last tour in 2019, Dylan gave "Honest With Me" an almost surf-rock vibe.

But "Love And Theft" itself remains that rare thing -- a Bob Dylan album that stands on its own, with no extraneous material distracting us from the unified whole. There's no New York Acetate or "Blind Willie McTell" for fans to argue about here. Coming from an artist who is far from a perfectionist, "Love And Theft" is perfect in its own way. Dylan couldn't help but agree. "I think of it more as a greatest hits album, Volume 1 or Volume 2," he claimed in the lead-up to its release. "Without the hits; not yet, anyway." Twenty years later, the songs on "Love And Theft" might not be hits exactly, but the album is certainly one of Bob Dylan's greatest.