We're in the midst of a pop-star documentary boom. The past few years have brought an onslaught of films promising authentic glimpses into the lives of glittering pop figures: the bracing Billie Eilish documentary The World's A Little Blurry, Taylor Swift's carefully orchestrated Miss Americana, Beyoncé's "Beychella" concert film Homecoming, even the Jonas Brothers jumping into the fray with Chasing Happiness. These movies give musicians -- and their management -- the chance to control their narratives; in return, fans get parceled-out morsels of intimacy. It's a contract between artist and viewer, a bargain we make again and again and again.

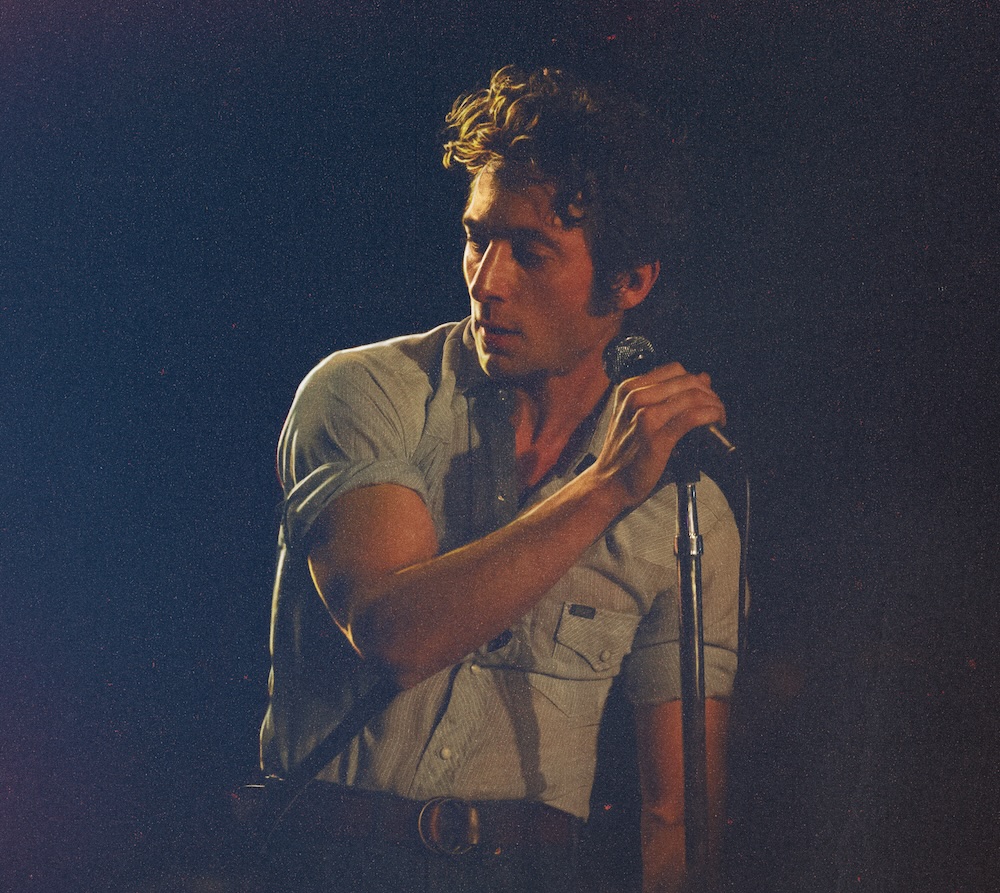

St. Vincent would be a fascinating subject for one of these films. Annie Clark's personal life and at times pugnacious attitude towards those inquiring about it -- see: her team allegedly killing an interview that asked about her views on prison abolition, her insistence on dodging questions, her well-documented hostility toward reporters -- has become entwined with her music. Clark and Carrie Brownstein’s new film, The Nowhere Inn, sets out to satirize the musician documentary industrial complex. What we get instead is a movie constantly negotiating with its sense of irony, charmed by its own cleverness while trying to be everything at once. Is it smuggling fan service into its arthouse shots, showing snippets of St. Vincent belting on stage with a ring of lipstick smudged around her mouth? Is it an extended Portlandia episode, with Brownstein's trademark are you kidding me expressions punctuating rigid scenes? Is it a story about the friendship between two supremely talented artists? Is it surrealist horror? Is it all just a joke?

To tease out a plot from the layers of meta-narrative: The film follows Brownstein -- the co-leader of Sleater-Kinney and co-creator of Portlandia -- as she attempts to make a documentary about her best friend, the sometimes sweet, sometimes awkward Annie Clark, who morphs into the leather-clad rockstar St. Vincent onstage. This, we're told, is a big opportunity for Brownstein; "This is my era of failure,” she tells Clark, and crafting the film offers a way out. The pressure makes her fumble -- she Googles "best documentaries" at one point, searching for a template.

The problem is that Clark herself presents as exceedingly boring. She works hard; she tries different kinds of radishes for fun; she plays Scrabble with her bandmates. Brownstein asks the people around St. Vincent to name anything interesting about the singer; they keep only referencing her music, until someone brings up the fact that her dad is in jail. Brownstein balks at this and refuses, at least at first, to incorporate it into her documentary. "I don’t want to exploit family drama," she insists, a cheeky nod to the new St. Vincent album inspired by her father's return from prison.

Brownstein tries increasingly elaborate stunts to coax Clark into creating captivating footage. She urges Clark to co-write a song with her, one whose progress they can chart over the documentary's narrative. She wheedles with Clark to throw a dance party on the tour bus. Eventually, Clark hits her breaking point. In a backstage interview before her concert, she contorts her voice into a purr, then reaches for a cigarette. Brownstein points out that she doesn't smoke. "This is how actors play rock stars in movies," Clark responds. "You are a rock star," Brownstein shoots back. Clark takes the act further and further, until the film seeps into a psychedelic horror.

The Nowhere Inn tries, desperately, to make a point: Fame is hard, celebrity is a trap, the art and the artist are both incontrovertibly linked and demonstrably deviated. At nearly every turn in the film, someone is always asking something from St. Vincent. A reporter stops mid-interview to answer texts from her girlfriend, then demands that Clark leave her a voice message insisting the reporter is not a bad person. (Later, after the reporter begs for a comped ticket for her cousin to see St. Vincent's show, Clark overhears her saying the singer is "impenetrable and aloof.") A fan tells her between gasps that St. Vincent's music is the reason she stayed alive after her boyfriend's death, and a struck Clark collapses into sobs in the dressing room.

The contradiction is painstakingly spelled out -- St. Vincent is so famous she has constant obligations, but not famous enough to be a household name. The film's first words come from a chauffeur driving a sunglasses-shrouded Clark through the desert in a gleaming white limo: "So you're a singer?" he says, the skepticism bare in his voice. "I've never heard of you." He calls up his son, who chimes in over speakerphone that he's never heard of her, either; when they ask for her to sing, she glides into a few lines of "New York," until they gasp at the line, "You’re the only motherfucker in this city who can handle me." ("Did she just say MF?" the son wheezes.) Later in the film, Clark forgets her badge and can't get into the theater for her own show. The walls outside are plastered with posters of her face -- "Dude?" she hisses at the security guard, pointing at them.

The Nowhere Inn slips moments of levity into all this self-conscious prodding. Director Bill Benz is a Portlandia alum, and he knows when to center on slight shifts in Brownstein's expression, the moments when a raised eyebrow or slow blink can make a scene. The only purely funny moment in the movie stems from a Dakota Jonson cameo, with the actress playing herself as Clark's newest celebrity girlfriend.

The sets and costumes are sumptuous, and the camera lets us drink it all in. Glittering dresses abound. Statues shine in the background. The lens shivers and blurs, red streaks oozing across the screen at times. There are so many shots of mirrors, so many heavy-handed metaphors: We see abundant refractions and reflections of Brownstein and Clark. But a film can't propel itself on symbolism alone.

Still, there are intriguing questions at the movie's core. "The audience doesn't need me," Clark says at one point, slamming her fist on a board room table. "I'm just a vessel for their feelings." At another point in the film, she insists: "I know who I am. Why does it matter if anyone else does?" It's hard to not to read this as a rebuke of St. Vincent's critics, or a blanket defense for her past media conduct, but interrogating what artists actually owe fans and vice versa is worthwhile and compelling. Instead, the movie sinks further into itself. While bending over backwards to assert that it's not your typical music star documentary, The Nowhere Inn achieves the same result as most films in that genre. We're left grasping at the idea of who St. Vincent is or could be; all we know for sure is how much she wants to prove.

The Nowhere Inn is out 9/17 on VOD and in select theaters.