You could make a case that the '90s started for real on Sept. 24, 1991. Thirty years ago today several landmark albums hit stores, releases that would define how the decade sounded and felt and would continue to influence rock music and pop culture at large. This truly stacked release date -- coupled with the previous day in the UK (albums dropped on Mondays, not Tuesdays, there in the '90s) -- saw the arrival of Nevermind by Nirvana, Blood Sugar Sex Magik by Red Hot Chili Peppers, Trompe Le Monde by Pixies, and Screamadelica by Primal Scream. (Incidentally, Soundgarden's Badmotorfinger was scheduled for 9/24 too before getting pushed back due to production delays. It's also very much worth noting that A Tribe Called Quest released the masterpiece The Low End Theory that week as well. And while Tribe are one of the quintessential "rap groups that rock fans love," that's an album for another story.)

This was the day that college radio-nurtured types and arty hard rock officially became rebranded as Alternative Rock and, according to legend, everything changed forever. Alternative rock had, of course, been around for a little while before it officially became Alternative Rock in 1991. The Cure, Depeche Mode, and R.E.M. were selling out arenas and lodging singles like "Just Like Heaven," "Enjoy The Silence," and "The One I Love" onto the pop charts, and college radio favorite Sinéad O’Connor had conquered the world with "Nothing Compares 2 U." But still, something was inarguably happening by 1991. Faith No More had recruited an elastic-voiced weirdo named Mike Patton to sing for them and scored an unlikely hit with "Epic." Perry Farrell's Lollapalooza tour, initially envisioned as a farewell party for his band Jane's Addiction, had been a surprise hit, bringing the likes of Nine Inch Nails, Butthole Surfers, and Siouxsie And The Banshees to audiences across the country.

Every generation has its defining myths, and the "Nirvana and the alt-rock boom killed hair metal and bubblegum pop" is certainly one of Generation X's most enduring narratives. But just as the original Woodstock was a filthy, borderline dangerous music festival that didn't exactly rid the world of war and bad vibes, the truth about what alternative rock did and did not accomplish is a bit murkier.

As the great critic Chuck Eddy once opined, hair metal was dying well before Nirvana arrived: "Glam poodles had wiped off their mascara and were trying to get serious -- Cinderella’s 1990 Heartbreak Station was a purist blues-rock record; Skid Row's Slave To The Grind, out in June 1991, was pop-shunning arena turbulence that went to #1 without a hit single." The world-dominating pair of Metallica and Guns N' Roses (The Black Album and Use Your Illusion I & II had just come out) probably deserves as much credit for making that genre look played out as any grunge act does.

Credit whomever you will, it's true that after Nevermind, Blood Sugar Sex Magik, Badmotorfinger (released a few weeks later), and Pearl Jam's Ten (released a few weeks earlier) began climbing the Billboard 200, hair metal groups were sent scrambling. Mötley Crüe would temporarily recruit singer John Corabi, rebrand their image, and try their hands at grungy alt-rock and Nine Inch Nails-style industrial crunch. (In a 1998 Spin profile written by their future biographer Neil Strauss, returned frontman Vince Neil would comment "right now we're just fighting to regain what we once had.") Poison would fire founding guitarist C.C. DeVille and try their hands at bluesy social commentary, barely eking out a Gold album and critical shrugs. But while neither act would ever return to their commercial glory days, both would eventually do fine for themselves in the world of VH1 reality shows and nostalgia-based summer package tours.

It's also hard to make the case that Nirvana and company truly killed off macho, swingin'-dick hard rock, as two years later Aerosmith, hardly anyone's ideas of sensitive artists, would release their most popular album Get A Grip and make a series of videos sexualizing Steven Tyler's young daughter. In fact, the '90s would see plenty of (problematic but often kinda awesome) knuckle-dragging, neanderthal metal bands like Korn and Pantera breaking through, giving lie to the idea that Kurt Cobain single-handedly cured the rock scene of any and all retrograde attitudes. Also, eventually, all the trend-chasing corporate rockers like Nickelback or Creed that would have been hair metal groups in an earlier era rebranded themselves as fake grunge bands anyway. The more things change, as it were.

Nevermind dethroning Michael Jackson's Dangerous from the #1 position on Billboard is a true changing of the guard moment, but it's not like big money, crowd-pleasing pop was going anywhere. Madonna and Whitney Houston were doing just fine for themselves, after all. But many of the teen pop acts that once dominated the airwaves even a few years prior were fighting the same cultural tides as the hair metal acts. New Kids On The Block would abbreviate their name to NKOTB and also attempt a serious, R&B-influenced rebrand, only to discover their audience had grown up, while Debbie Gibson failed to find much success with her 1993 effort Body, Mind, Soul and would eventually make the sensible decision to focus on musical theater. So yes, teen pop was gone for a moment, but that had as much to do with its audience growing up as with alternative rock replacing it, and by the end of the '90s it would all be back in a big way.

But just because a myth can be over-inflated doesn't mean there's no power or truth to it. Every generation -- or micro-generation, or heck, new crop of incoming college freshmen -- wants to claim ownership over the world and things that feel like the culture now belongs to them. It's one of the reasons there are a million subgenre names for a few basic music forms. It’s an easy way to break from history and start again. And the kids needed a break by 1991, as very few heroes of the '80s would prove to have Madonna's knack for reinvention or David Bowie's knack for growing into an Elder Statesman role. Shit had gotten stale; time for some new blood. The success of these albums, along with Ten, truly did set the stage for the alt-rock boom.

To see the immediate impact, just look at the inaugural Lollapalooza, an underground phenomenon that managed to gross $9 million. The follow-up more than doubled that. Suburban teens lured in by MTV playing the videos for "Smells Like Teen Spirit," "Rusty Cage," "Jeremy," and "Under The Bridge" seemingly on a loop were busy denying they ever liked Skid Row and flocking to the 1992 edition of Lolla, which featured Soundgarden, Pearl Jam, and headliners Red Hot Chili Peppers. A curious media desperate to look hip to the next youth culture trend followed.

Suddenly, everyone wanted to know what exactly "alternative" meant, and how they could get a piece of it. Ted Gardner, former tour manager for Jane's Addiction and co-founder of Lollapalooza later recalled. "In '91, there was an element of risk. It was like, 'God, what if this is a dismal failure?' In '92, we were getting offered Corvettes. There was a promoter that said, 'Play my venue, and I'll get you all Corvettes.'"

It's easy to bemoan all the watered-down copycats that got signed in the wake of the alt-rock boom. I mean, I just did that a few paragraphs back. But the success of Nevermind and Badmotorfinger certainly prompted major labels to be a bit more adventurous than they had before. Arguably too adventurous at times, as defiantly uncommercial acts like Melvins, the Jesus Lizard, and Daniel Johnston had no real business being on a major label.

Mercurial Weezer frontman Rivers Cuomo told Rolling Stone: "I probably wrote 'The Sweater Song' and 'The World Has Turned And Left Me Here' and 'My Name Is Jonas'" shortly after hearing Nevermind. It felt so close to what I wanted to do." And DGC Records founder David Geffen wouldn't have called Beck at home after hearing "Loser" if he wasn't looking to keep the alt-rock boom going. "It kinda seems like anybody can just get up and make a racket these days. Anything goes now, I guess," Beck would muse shortly after the release of his major-label debut Mellow Gold.

By the '90s, the music industry was flush thanks to the revenue generated by the explosive popularity of CDs and MTV superstars such as Michael Jackson and Madonna, and major labels were pretty much willing to take a chance on everything, as Janet Billig Rich, former manager to Nirvana, Smashing Pumpkins, Hole, and the Lemonheads would later recall to NPR. "Everyone was a little shocked. Everything got really easy because it was this economy -- Nirvana became an economy." Punk-leaning but reasonably hooky groups like Jawbox were getting deals, only to be shunned when great albums like For Your Own Special Sweetheart didn't sell like Blood Sugar Sex Magik. And while the New York heavy metal band Helmet's major-label debut Meantime featured some of the toughest riffs ever recorded, it’s still absurd that a major label paid a million dollars for a band this abrasive in hopes it would become the next Nirvana. (Even frontman Page Hamilton knew it was insane that A&R men told him his band could be as big as U2.)

It was an exciting time for music fans, especially for anyone who was coming of age then and was lucky enough to have their tastes shaped by a forward-thinking era. But there was also a darkness. Red Hot Chili Peppers guitarist John Frusciante quit the band in the middle of their Blood Sugar Sex Magik world tour, unable to deal with the attention of suddenly being actually real world-famous. "Everything seemed to be happening at once and I just couldn't cope with it," he recalled upon rejoining the band at the end of the decade. Frusciante spent the intervening years descending into heroin addiction, later telling Rolling Stone: "I just didn’t care what was going to happen to me. I always thought I was very close to dying."

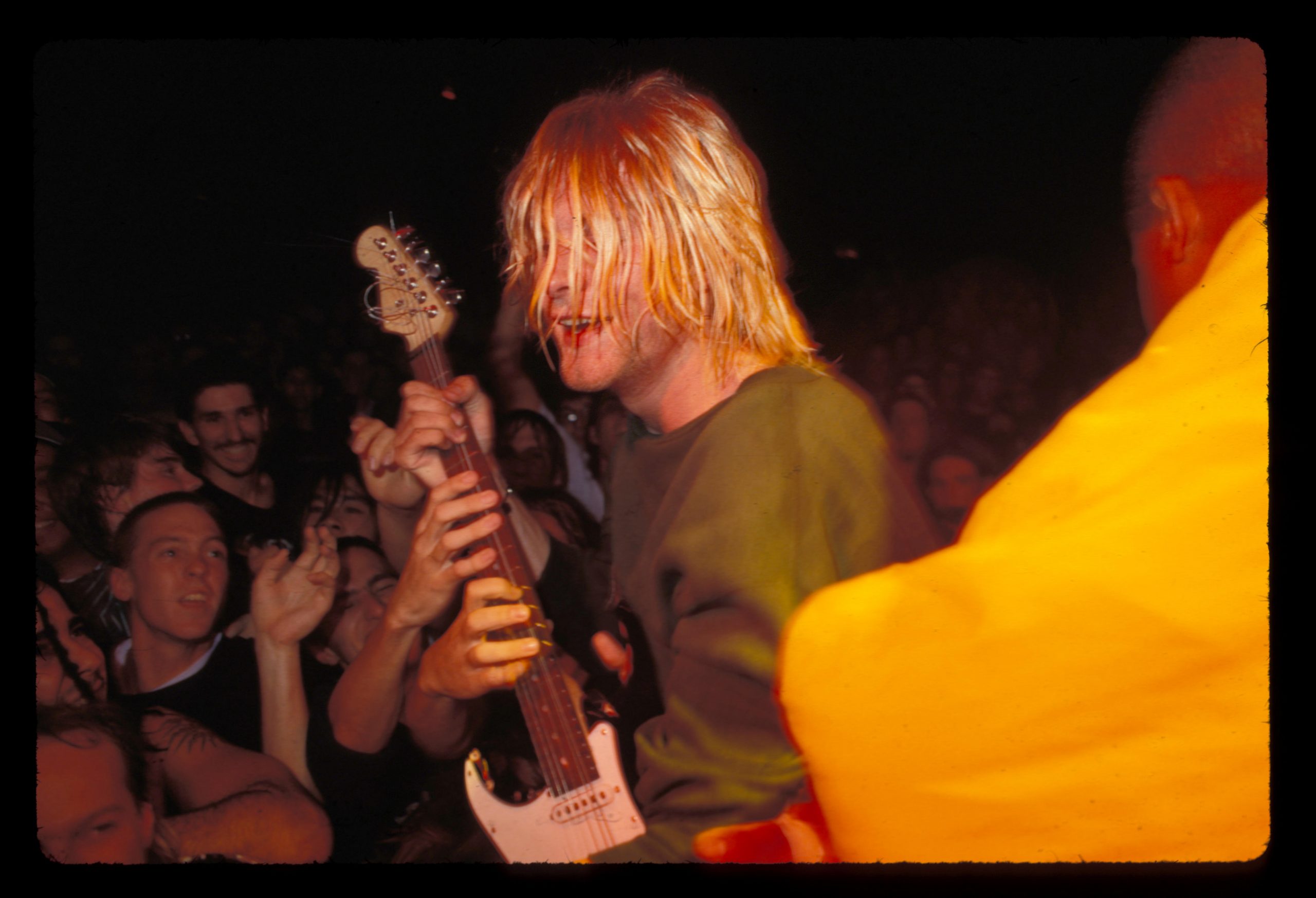

Mental health and addiction are vastly complicated things, and it would be reductive and ghoulish to attribute Cobain's battles with heroin and depression and eventual suicide to his discomfort with fame, or to any one cause, really. But it's abundantly clear that going from an unknown punk happy to grind it out in a small club to the Spokesman Of A Generation in a year took a toll on him.

Cobain's suicide is often pointed to as the end of the alternative era. Others point to the riots of Woodstock '99, and that year’s cultural ascendency of sexist nu-metal groups and teen-pop superstars, the sort of thing Nirvana and company supposedly killed, as the end. While on the other side of the pond, the hedonistic Madchester dance-rock scene that Primal Scream helped create with their landmark rave 'n roll album Screamadelica was more or less declared DOA after the Stone Roses took five years to follow-up to their massively influential debut LP. Second Coming, a muddled departure from the house music-influenced sound, was met with a harsh reaction from critics and fans, who had largely moved onto Britpop groups like Oasis and Blur.

However it happened, the Alternative Rock boom wasn't going to last forever. But when music makes an impact, when it truly connects with people and brings something to their lives, be it joy, a different perspective on what art can do, or an outlet for the frustrations and struggles we all deal with, it has a tendency to outlast any given era. It's also likely to get passed down through the years, continually rediscovered by fans and artists looking for fresh inspiration.

The albums released 30 years ago this week would help shape the way alternative rock, punk, indie, and metal would sound and feel to this day, and you could certainly make an argument that there's bits and pieces of all of them in triumphant 2021 albums like Turnstile's Glow On. While it would take a while to get the rock kids to fully embrace rave culture, you can draw a straight line from the Rolling Stones-on-ecstasy bliss of Screamadelica to Noel Gallagher duetting with the Chemical Brothers to every long-running band eventually having A Dance Music Phase.

Because Trompe Le Monde doesn't feature a Kim Deal feature on the level of "Gigantic," and didn't bring much new to the legendary band's groundbreaking sound, and because the band broke up acrimoniously shortly after its release, it tends to get treated like the runt of the litter. But it's still an album by the Pixies in their prime, which means it still rules, and going out on such a caustic, yet kinda funny (the higher education kiss-off "U-Mass" is hilarious) high note certainly helped seal this group's legend, ensuring that young bands would continue to mine their inimitable combination of freaked-out whimsy for inspiration.

Nirvana, Soundgarden, and Red Hot Chili Peppers don't sound particularly similar, but they all came into their own in 1991. Their common link is that, in their own ways, they all made the argument that rock music -- by which I mean body-first, hefty, hard-rawking rock music -- works best when it's open to other ideas and not exclusively concerned with kicking ass. (Though kicking ass is important.) By blending elements of lo-fi whimsical punk (Nirvana), art-rock grandeur and Sonic Youth/SST-derived alternate tuning and odd song structures (Soundgarden), and deep, P-funk and Meters-derived grooves and LA punk abandon (Red Hot Chili Peppers) into classic rock songwriting, they helped set the template for the anything-goes, mix-and-match ethos that would define the '90s and now seems standard in these genreless times.

The other great innovation of Cobain and Chris Cornell, and to a lesser but still valid extent Anthony Kiedis, is that they helped create a more vulnerable and introspective rock star that helped remove the toxic machismo from rock' n' roll swagger, at least for a while, at least in their corner of the world. (Again, Kiedis was only occasionally capable of this, but you gotta give him "Under the Bridge" and "I Could Have Lied.")

It's the contrasts -- between power and empathy, the past and the future, the regard for rock's past and the disregard for its boundaries -- that are why these artists all endure to this day, influencing musicians that don't even particularly take sonic cues from them, such as Julien Baker, Lil Nas X, Post Malone, Brandi Carlile, and Miley Cyrus. Lorde said she hadn't heard of the Screamadelica single "Movin’ On Up" before writing the borderline homage "Solar Power," but sometimes art becomes so powerful and influential that it influences the culture almost by osmosis.

Generation X grew up in the long shadow of the Baby Boomers, and were often told it had all been done before, and better. But starting 30 years ago, the children of the boomers began writing their own story, proving they could measure up to and surpass their parents' cultural hand-me-downs. Every generation deserves the right to remake the culture in its own image without a bunch of adults complaining that it's not like it was back in the day, and I hope all the aging alts keep their grumbles to themselves while the kids try to figure it out for themselves. But the past is always there in the present and the future, and no matter what comes from next, the impact of these albums will likely continue to linger.