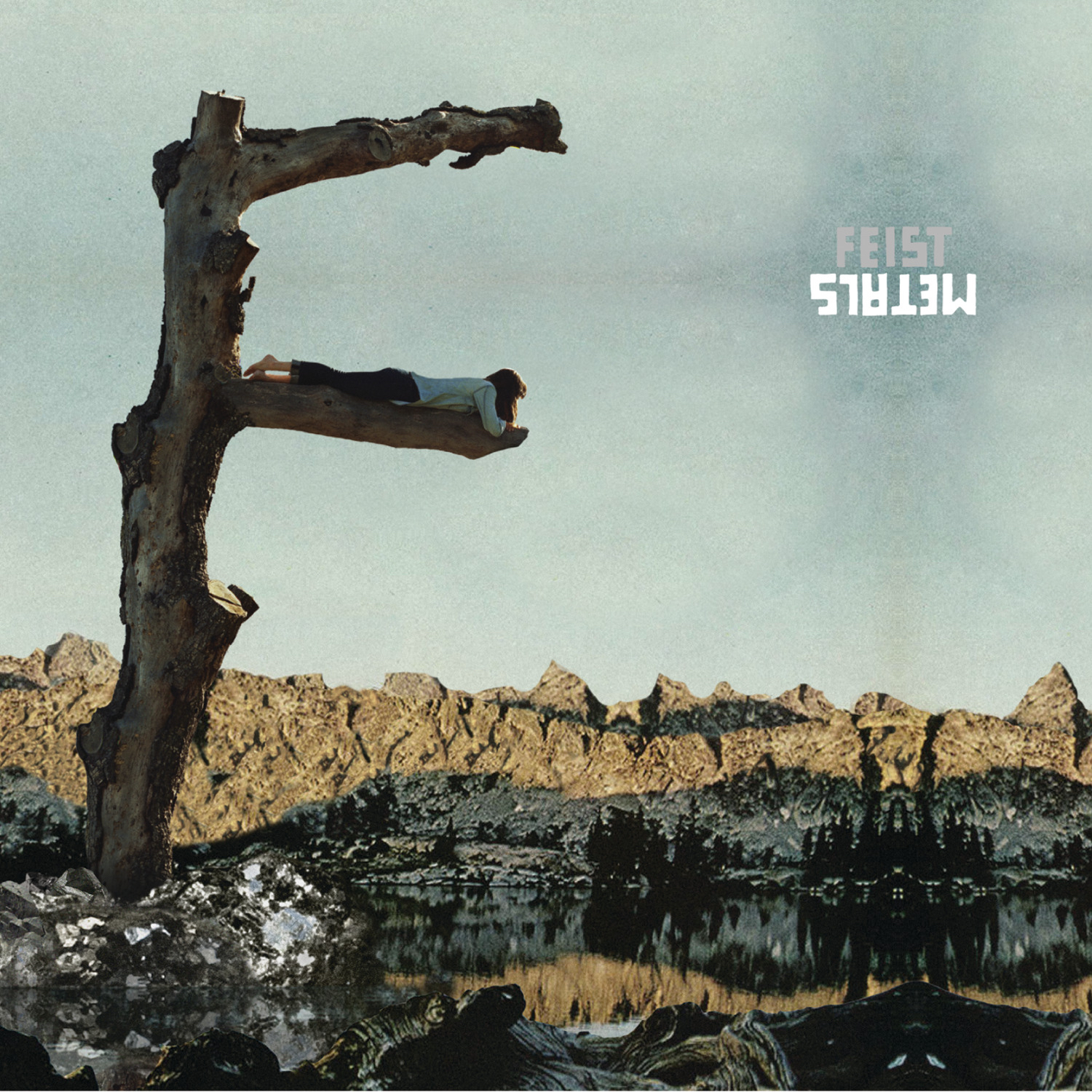

- Arts & Crafts/Cherrytree/Polydor

- 2011

There are hit songs, and then there are songs that seem to permeate every fibre of popular culture, like cigarette smoke on a denim jacket. Feist's "1234" was such a song. The numbers don’t lie: a Top 10 single in the US, Canada, and the UK, "1234" propelled sales of the Canadian singer's 2007 album, The Reminder, past the 2 million mark. But such metrics don’t tell the full story of the song’s sheer ubiquity and its grade-schoolers-to-grandmas cross-generational appeal.

Emerging at a time when movies like Juno and Nick & Norah's Infinite Playlist were smuggling quirky indie sensibilities into the mainstream, and Wes Anderson characters had become Halloween-costume staples, "1234" was the undisputed national anthem of Twee Nation, as consecrated with its rainbow-hued flash-mob of a video. The song’s ascent was expedited, of course, by its prominent placement in an iPod Nano ad -- which, for an indie-bred artist in 2007, was the equivalent of winning the Super Bowl, Survivor, and Powerball all at once. But where a hit song will typically get you an invitation to perform on Conan, Letterman, and SNL (as Feist did), "1234" holds the rare distinction of being parodied on MAD-TV, written into an episode of The Office, and featured in a Sesame Street segment, that, to date, has taught kids how to count nearly a billion times.

Of course, when a song becomes that inescapable, it's only a matter of time before you get sick of it. And, arguably, by the end of 2008, no one was more sick of "1234" than Leslie Feist herself. Part of that had to do with the fact her most popular song was arguably her least representative -- a rare, radiant burst of sunshine from an artist who's always done their most compelling work lurking in the shadows. It also wasn't actually hers to begin with: originally crafted by Feist's one-time tourmate Sally Seltemann (aka Australian art-pop chameleon New Buffalo), "1234" blossomed into a songwriting collaboration between the two. "I co-wrote it and arranged it and made it into a piece of The Reminder's puzzle," Feist told Pitchfork, "but it's [Seltmann]'s sentiment. It functioned inside the album, but when it was plucked out, it had less to do with the record than any other song on it. '1234' started to speak on its own behalf."

After winding down The Reminder's tour cycle with a cross-Canada victory lap in the fall of 2008 -- which included the biggest headlining show of her career at Toronto’s Air Canada Centre -- Feist not only took a much-needed break from the road, she didn't pick up an instrument or write a song for a good two years. ("I was so depleted," she said.) When she began actively touring again in 2011, "1234" was conspicuously scrubbed from the setlist. And the new album she was promoting at the time, Metals, wasn’t going to spoon-feed audiences a "5678."

The "difficult" post-success album is such a common knee-jerk response to sudden fame, it practically continues a genre unto itself. From Neil Young's Ditch Trilogy to Fleetwood Mac's Tusk to Nirvana’s In Utero to Radiohead's Kid A, the history of rock is full of chart-topping artists who were willing to sacrifice their stardom to prove they’re not just another pop product. On its own modest terms, Metals belongs to this lineage -- though in Feist’s case, she wasn't so much violently sabotaging her newfound celebrity as recognizing that her artistry doesn’t so easily conform to a music industry whose only guiding principle is to scale up. "In music, there's always talk about [audience] growth, but I really don't think in those terms," she said in a 2012 interview. "Bigger shows can feel totally void of connectivity with music. I don't really strive to have anything get bigger, I just want to have something where it feels like I'm present, and actually exchange something with people who are at the show. Playing the Air Canada Centre really wasn't like that."

But if Metals, released 10 years ago today, was intended to be more intimate by design -- forsaking arena ambitions for a more attentive cathedral-sized experience -- that intimacy doesn't necessarily translate into "quiet." While Feist first attracted international attention in the early 2000s as a cog in the Broken Social Scene machine, by Metals, she had amassed a volatile, hydra-headed indie-rockestra of her own, one that included avant-saxmaster Colin Stetson, Constantines frontman Bry Webb, Beck keyboardist Brian LeBarton, BSS/Stars member Evan Cranley, San Francisco ensemble the Real Vocal String Quartet, and Apostle Of Hustle drummer Dean Stone, alongside her perennial producers/sounding boards Chilly Gonzales and Mocky. Collectively, they don’t so much reinvent Feist’s sound as emphasize the restless physicality that's always been part of her musical DNA, particularly in concert: the floorboard-shaking foot stomps, the participatory handclap hooks, her beautifully serrated guitar-playing.

Feist’s recordings have always coloured by their external environments: think of the street traffic humming in the background of her Red Demos tape (recorded in the second-floor-living-without-a-yard Toronto apartment she once shared with Peaches) or the Parisian je ne sais quoi embedded in the wistful melodies and smoke-ringed arrangements of 2004’s Let It Die and The Reminder, both made in the City of Light. For Metals, the location shifted to Big Sur, and while there’s little that feels classically Californian about the record, it does very much mirror the region's unique topography -- this is an album imbued with a bucolic serenity that's routinely disrupted by crashing tidal waves.

Feist's preceding records were liable to make you spontaneously float away; Metals drops you at the base of the mountain and dares you to climb up its jagged rockface. The album doesn’t waste any time anyone weeding out casual fans coming here for more Apple-approved pretty ditties. While opening track "The Bad In Each Other" may set a familiar Feistian scene of a relationship at the breaking point, the song's tremulous percussion, ominous orchestration, and stentorian brass drones frame this lovers quarrel as a gladiator duel. But rather than set up a typical he-said/she-said dynamic, Feist invites Webb to sing the crestfallen chorus with her in unison, a move that amplifies the deep-seated regret, exhaustion, and mutually assured emotional destruction at the core of the song. Essentially, "The Bad In Each Other" is the doomed second act of a narrative that began with Feist and Webb's previous duet, a cover of Kenny and Dolly’s lovey-dovey karaoke classic "Islands In The Stream."

Moreso than her previous work, Metals displays a pronounced directorial vision with each track staged like a theatrical production, her collaborators appearing more like characters. Amid the tense, slasher-movie strings of "A Commotion," she rallies her male bandmates to deliver the song’s jump-scare chorus. As she embarks on the mountain-climbing odyssey of "The Undiscovered First," the Real Vocal String Quartet serve as her supportive chain-gang, as they collectively trudge toward the song’s triumphant climax. The caustic "Comfort Me" perfectly crystallizes Metals' auteurist aesthetic: What begins as a hushed folk-blues kiss-off ("When you comfort me/ It doesn't bring me comfort actually") erupts into a bolder statement of independence, complete with taunting group vocals and pounding caveman percussion—the sound of Feist defiantly walking to the beat of her own drum. But on Metals -- and across Feist's entire discography to date -- there is no more powerful moment than "Graveyard," a solemn late-night cemetery seance that, with the help of the RVSQ, gradually intensifies into a more aggressive effort to wake the dead. My personal attachment to this track is admittedly colored by the fact that, shortly before Metals' release, I lost my father, so I was squarely in the target demographic for a song that repeatedly screams "Bring 'em all back to life!" But "Graveyard" still fascinates because it makes sadness sound like celebration and vice versa, capturing both the eternal hope and frustrating futility of trying to commune with the afterlife.

The aforementioned songs count as both the grittiest and most grandiose works in the Feist canon, and they effectively planted the seeds for her unlikely mutual-appreciation society with metal overlords Mastodon. But for the most part, Metals follows a rollercoaster sequence, where these skyscraping peaks are followed by dramatic drops into the most desolate valleys. If Metals' louder tracks harness the awesome power of nature—conjuring the sound of thunder and earthquakes and hailstorms -- candlelit reprieves like "Caught A Long Wind" and "Cicadas & Gulls" forge a more peaceful relationship with the great outdoors, where a humbling reverence for our surroundings and the creatures that populate them can inspire a more intense mode of self-reflection. "I'll head out to horizon lines/ Get some clarity oceanside," she sings on the delicately divine "The Circle Married The Line," using the simple geometric image of a sunset to illustrate the harmony that can exist between seemingly incompatible partners or forces.

Or in Feist’s case, "The Circle Married The Line" could represent the potentially fragile or fruitful relationship between her artistic explorations and audience expectations. Ironically, just as "1234" was an outlier on The Reminder, Metals' slow-burning lead single “How Come You Never Go There" was something of an anomaly on this record, coolly slinking somewhere in between its volcanic highs and vulnerable lows. While it may not have been a "1234"-sized instant earworm, the song kept enough fans onside to propel Metals to #7 on the Billboard 200 the week of its release in October 2011. But even though it stands as Feist's highest-charting record to date, Metals feels today more like a vastly underrated career milestone.

Now, that might seem like a weird thing to say about a Top 10 record that scored an average of 81 on Metacritic, got named album of the year by the New York Times, and won Canada's Polaris Music Prize. But to this day, Metals has been largely overshadowed by The Reminder's lingering pop-cultural footprint. Unlike its predecessor, Metals didn’t spawn a monster hit single, or an iconic cover version by a hip left-field artist, or have any of its songs land on Beyonce’s wedding-anniversary playlist or inspire lip-sync battles in the Eilish family sedan. In hindsight, Metals appears as a line in the sand marking the end of indie’s pre-streaming era, as the album's tactile nature and rambunctious communal energy put it increasingly at odds with a genre that algorithmically shifted toward smoother, more digitized, and sync-friendly sounds over the course of the 2010s.

But if The Reminder brought Feist global commercial success, Metals gave her something money can't buy -- i.e., the confidence that enough loyal fans would stick by her no matter how far out she ventured, and no matter how long it took. It's a don’t-look-back ethos she's since carried over to her next album, 2017's proudly lo-fi Pleasure, and to her current interactive, site-specific concert series, Multitudes. And when you look out at the pop landscape circa now, you'll find a lot of emboldened hitmakers -- Lorde, Billie Eilish, Halsey, Clairo -- who've entered a Metals-type phase of their own, pursuing their peculiar visions at all costs, charts and trends be damned. (You could also make the case that, with its percussive shocks and cathartic chants, Metals was rattling the locks on the same maintenance closet from which the boltcutters would later be fetched.) On Metals' closing track, Feist finds herself far away from the world of hockey-rink concerts and Grammy red carpets, hiding in trees and skipping stones on the river as she ponders a career at the crossroads of fleeting fame and carefully cultivated longevity. "Get it wrong/ Get it right," she sings on the track of the same name. Ten years on, she's still basking in the freedoms that Metals granted her: the fearless determination to make all the right wrong moves.