Lil Wayne's verse on Tyler, The Creator's "Hot Wind Blows" begins with a familiar Weezy simile. The N'Awlins-bred emcee has just stopped the beat and said "excuse me, pardon me," like an elder preacher beginning a sermon. A bar later, he is lumping the hard-blowing wind into Mother Nature's family tree like it's "arguing about some baby father beef." It is a multi-layered line; you have to play it back to catch the intricacies of what he is saying. From there, Weezy is an auteur, bounding into Tyler's world of colors and elements and playing off of him. He even stops and gets sentimental about gracefully aging: "Thought all this lean would have me senile/ I guess they see now."

Tyler was rapping his ass off before this verse, as he does throughout his new Call Me If You Get Lost, but Wayne lets us know how easy-going the best emcees sound while still splitting your head open. When he starts rapping fast, it doesn’t feel like a gimmick or a show of empty technical prowess. Weezy is rapping that way because he fucking loves to rap. Finally, as the verse ends, he hits us with yet another double entendre: "The wind beneath my wings/ Desert Eagle underneath my coat." He sounds rejuvenated.

It isn’t only that verse, either. On Nicki Minaj’s reissue of Beam Me Up Scotty, Wayne is in rare form again, using onomatopoeia like "Ms. Cita told me to stunt my ass off/ Bapapapapa, he was a good cat, my bad dog." He's even discovering new rhyme scheme tricks. Peak Wayne’s rapping style was more abstract and wild than precise and technical. He’d come up with metaphors and punchlines like "Bullets like birds, you can hear them bitches humming/ Don't let that bird shit, he got a weak stomach." But on "Seeing Green," he combines metaphors with assonance that you usually hear from Golden Age stalwarts like Rakim or even Aquemini-era André 3000. After name dropping his mom, he says: "The cash blue, but I'm still seein' green/ I'm in the bathroom, and I'm peein' lean/ My bitch a vacuum/ I told her, 'Keep me clean,' the scene serene/ I'm a badonkadonk and bikini fiend."

In the mid-2010s, Wayne looked like he was losing his luster as a rapper. Albums like I Am Not A Human Being II felt like someone who sounded like Wayne was doing a cheap imitation of prime Wayne. His metaphors no longer sent you scrambling to double-check the lyrics. Bars like "With her brain, she could make the honor roll/ And when I came, she caught me like the common cold" were laughed at. People shook their heads and concluded that Wayne had really lost it. #LilWayneSaid was a hashtag on Twitter that existed from 2013-2016, and the tweets were not complimentary.

His relationships had soured, as well. In 2014, Wayne tweeted that Birdman was not allowing him to release Tha Carter V and that his creativity was being held prisoner. The only thing that is promised with any rap dynasty is the eventual dissolution, but this one was a tough pill to swallow. Lil Wayne and Birdman had been Stunna and Birdman Jr. Their collaborative album, 2006's Like Father Like Son, is the sound of Wayne becoming a boss like his "Godfather." For fans who'd long revered their partnership, that divide was almost as painful as Wayne's slump itself.

It's safe to say that Wayne's creativity is no longer being held prisoner. On Certified Lover Boy highlight "You Only Live Twice," Weezy easily overshadows Drake's single-dad raps. Wayne raps with the cockiness of Ricky Bobby in the middle of Talladega Nights, serving up buzzing lyricism like "I'm a dog, if you a dog, then pull your tail up out your ass/ And on this codeine, I'm a turtle, it done shell-shocked my ass." He is rapping like he is making a tape with DJ Drama again.

The hot streak continues with his appearance on AZ's Doe Or Die II. On "Ritual," Wayne out-maneuvers his fellow guest artist Conway The Machine with sexually charged rhymes reminiscent of his Da Drought 3 era. "I make love then sense, I make her friends kiss/ But she don't let 'em kiss me, she make her friend sick." Some rappers are terrible at rapping about sex -- including Weezy when he's off his game (please reference the facepalm-inducing bars cited earlier). But at his best, Wayne addresses the subject with an audaciousness that is infectious.

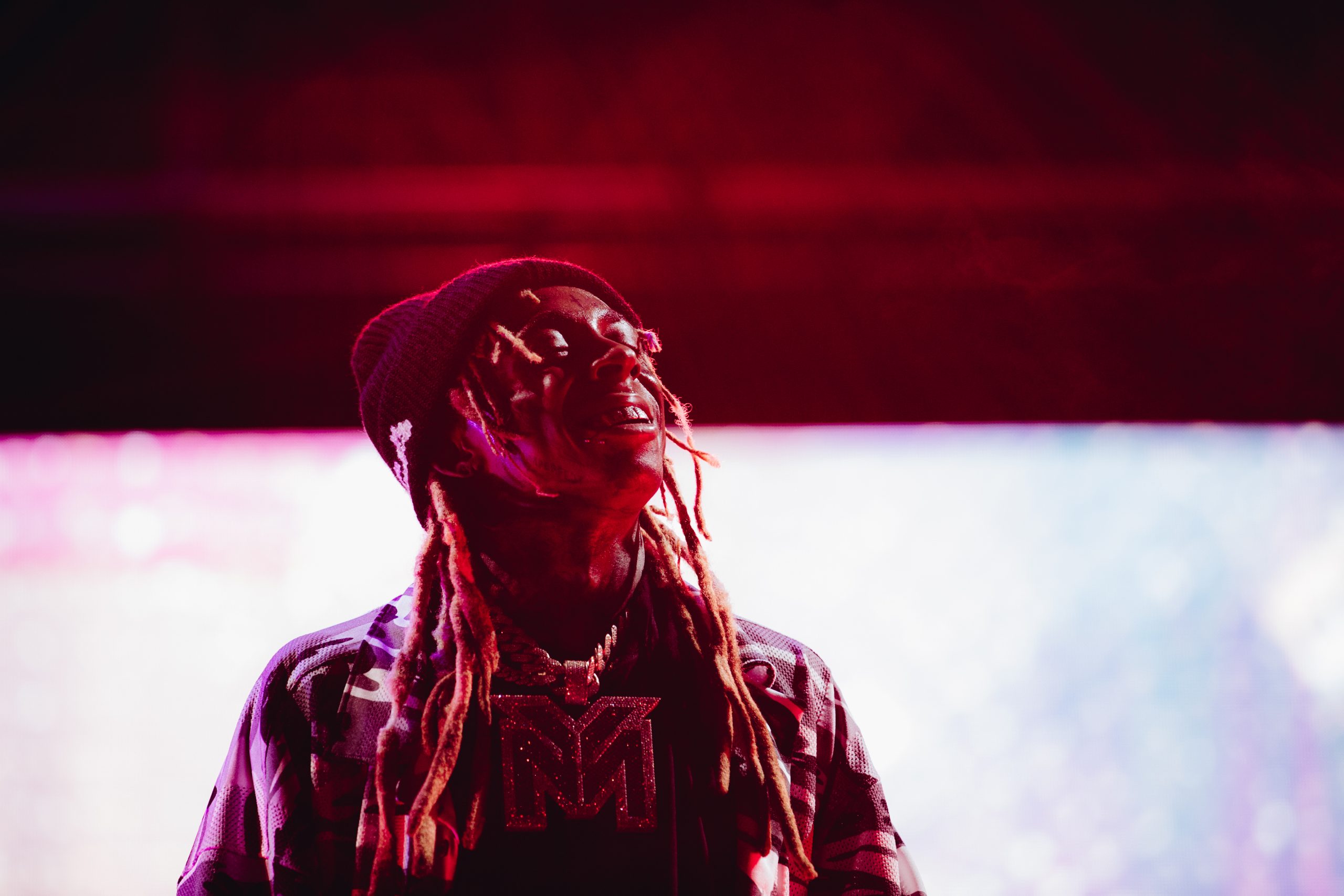

The best aspect of Weezy's current feature run is that he is shredding public expectations of older rappers. Old-man emcees, like current Jay-Z for example, are usually respectable and buttoned-up. They're pivoting to raps that function as self-mythology as much as actual music. Wayne turned 39 years old this week, but he isn’t rapping about piling up crypto money like a character in Billions. He isn't wagging his finger at the younger generation, either. On the contrary, he is reveling in proving that he can still compete with them. On the brink of 40, Wayne is out-rapping the rappers that he helped inspire -- a group that includes nearly everyone in today's rap landscape, especially those building their following one mixtape at a time.

Despite dynamic releases like Tha Carter II, albums were never Wayne’s forté. Although he was getting back in the zone with Tha Carter V, which finally dropped in 2018, it makes sense that a run of guest verses would be where he truly returns to legendary form. He built his "best rapper alive" reputation largely by stealing other people's tracks from them, either via official features or by rapping over the beats from popular songs on releases like Dedication 2 and Da Drought 3. What he lacked in classic LPs, Wayne made up for by revolutionizing the mixtape game and exhibiting a work ethic like post-jail 2Pac. Future's mixtape run wouldn't exist without Wayne. So much of modern rap wouldn’t exist without Wayne. He's the blueprint.

Wayne isn’t trying to be someone who he isn't within his music. He knows that the best way to age gracefully in rap is to simply rap well. Wayne isn’t going to make 4:44, an album that tells me that buying artwork and being a landlord is going to leave my family a legacy. Instead, he is going to show me that you can still have as much fun in middle age as you did in your twenties. It is often said that Jay-Z has more longevity than Wayne and that Wayne has a better peak, but the opposite is true. Wayne can't compete with Jay-Z's stretch of classics in the mid-'90s to early 2000s, but at 39, he is trouncing the prosperity-gospel raps Jay was kicking out at that age.

One of the many reasons why this recent run has been excellent is where Wayne was a few years ago personally. He had health problems, including a serious seizure in 2017 that left him hospitalized. He didn’t look good. He seemed to be as skinny as he was when he was in his teens, rapping alongside Juvenile, BG, and Turk. His voice was getting screechy. Now, his on-record swagger and smile are back. Rappers, like many Black men of all backgrounds, have struggled with their health as they've gotten older. Pimp C died at age 33. We just lost DMX at age 50. Sean Price died in his sleep at age 43. The list goes on. With Weezy's alleged use of lean and mental health issues, there was a reason to worry that we would lose him as well. But he’s still here rapping with fury, never letting you forget that he is one of the greatest rap superstars of our time.