- RCA/Polo Grounds

- 2011

If you were alive, online, and listening to hip-hop in 2011, the words "'Purple Swag' music video" wield an awesome, terrible power as a wormhole back to that summer. The still thumbnail image conjured by said phrase, a young white woman mugging for the camera in gold bottoms, is iconic: the blonde Trojan Horse bearing A$AP Rocky into public consciousness. As a whole, the music video’s no work of genius, but it’s catchy and magnetic. The same could be said for A$AP Rocky the rapper.

Of course, a woman named "Anna Trill" (no, I’m not making that up) lip-syncing along with some questionable-for-a-caucasian lyrics was not entirely or even mostly responsible for breaking Rocky into the national spotlight. In the years before the Harlem native made his under-the-radar debut with Deep Purple, the tape housing "Purple Swag," his collaborator and longtime friend A$AP Yams had been building a following on Tumblr, which became instrumental in marketing Rocky’s music.

"[Yams] was a big Tumblr name already," Rocky said in a 2018 interview with Desus and Mero. "He would sneak our stuff in there and they ain't even know he had affiliation with me or nothing... He'd just be like, 'Yo I like this kid from Harlem, but I don't know where he's from, it might be Texas, it might be LA.' So he'd put that out there because he's trying to make it seem like he didn't know me like that. He'd be throwing up mad relevant shit and then just put me in the mix of it."

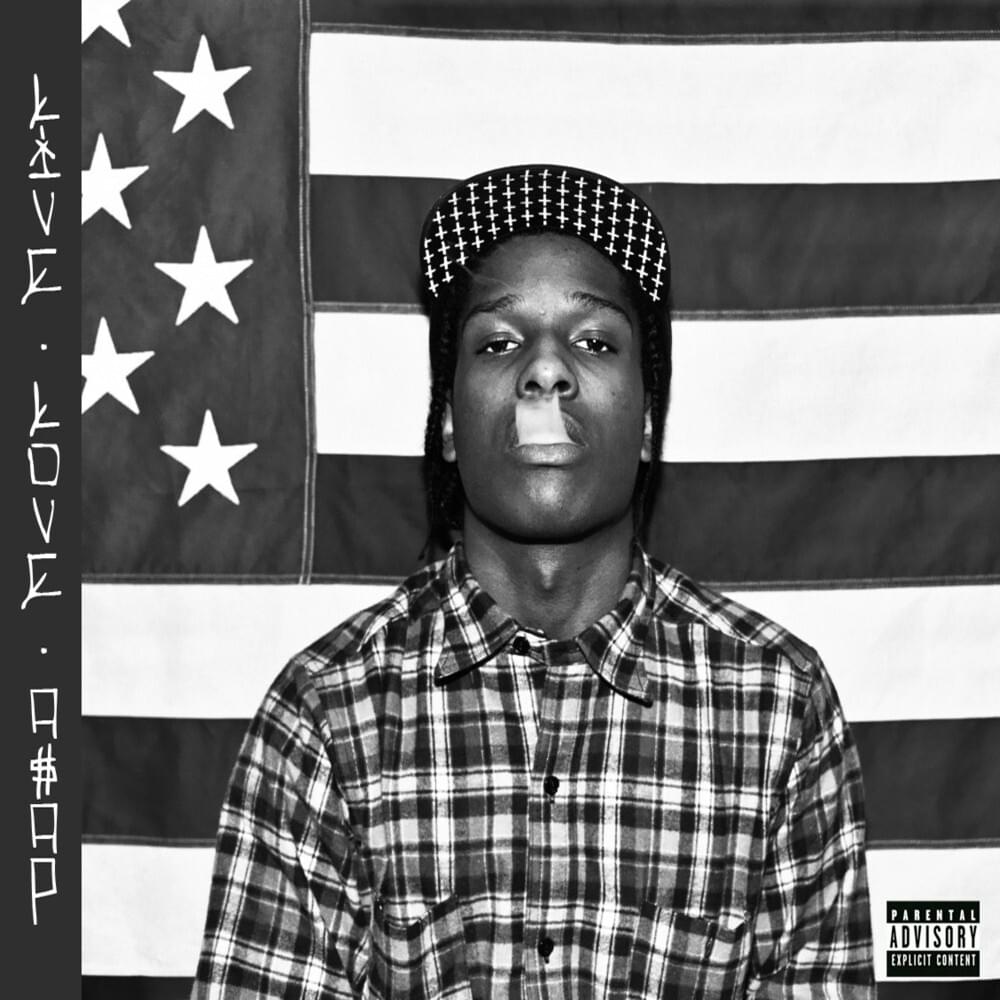

"Peso," teased in chopped-and-screwed form within the "Purple Swag" video, shortly followed, as did news of Rocky inking a lucrative deal with RCA/Polo Grounds. New York institutions like Hot 97 and Dipset, who brought Rocky onstage at a September 2011 show, got on board. By the time LIVE.LOVE.A$AP was released 10 years ago this Halloween, Rocky had graduated from internet hype. He and the rest of A$AP Mob were tapped as the Next Big Thing that New York had been unsuccessfully searching for since the mid 2000s. Everything else around them was too niche. French Montana had amassed a mixtape empire but wouldn’t release his first major label single until 2012; Action Bronson was still the former chef who sounded like Ghostface; Roc Marciano had only just begun amassing his cult following; guys like Fred The Godson and Vado were too orthodox to blow up outside of the Five Boroughs. Rocky had a star quality the city hadn’t seen since 50 Cent (just look at that perfectly executed French inhale on the mixtape cover!). But there was one facet of Rocky’s whole package that people couldn’t wrap their heads around at the time: His music didn’t sound like New York hip-hop.

Now, that’s a pretty arbitrary genre descriptor, but it was blatantly obvious that Rocky’s biggest influences were artists from the South and Midwest. Amid pre-Migos triplet flows on LIVE.LOVE.A$AP, he gloats about being the “only Harlem n**** on his Bone shit,” mentions syrup and the color purple at a Big Moe rate, and name-checks Southern classics like Master P’s “Bout It, Bout It” and Lil Keke’s “Chunk Up The Deuce.” Labels, critics, and listeners alike had no idea how to reckon with a native of the hip-hop mecca -- who was literally named after the God MC (Rocky was born Rakim Mayers; his sister Erika was named after Eric B.) -- seemingly ignoring his surroundings and burrowing into internet-based fandom of smoked-out Southern rap.

"It didn't sound like anything that was coming from New York," said Polo Grounds president and fellow Harlem native Bryan Leach soon after signing Rocky. In his review, The New York Times’ Jon Caramanica called LLA “placeless and universal, an album that sounds as if it has ingested the last 20 years of hip-hop’s travels and would be comfortable anywhere.” As the decade progressed, Rocky’s tape became the powderkeg for proclamations about a new, “post-regional” era in hip hop. Longtime hip-hop journalist Shawn Setaro penned an essay for Observer suggesting that “The rapidity of global communication has turned the idea of regional styles on its head.” “What all of this mixture shows is that mainstream rap is now, rather than a collection of folk musics,” he wrote, “a big, primarily Southern stew,” citing the influence of Memphis, Houston, and Atlanta on Rocky and others like Drake, Jay Z, and Kanye West. Hell, a McGill University student even wrote a thesis on “post-regionalism” in hip hop last year.

The regionless nature of Rocky’s music, which Yams alluded to in his facetious Tumblr posts, was flaunted more obviously than it ever had been in hip-hop. “Don't remember me as a wannabe New Orleans n**** / Slash lean sipping, Tennessee n****, nah / Influenced by Houston, hear it in my music / A trill n**** to the truest, show you how to do this,” Rocky raps on LLA opener “Palace,” getting out ahead of critics in an effort to contextualize his music, but muddying the waters even further. “I don’t even like New York rappers,” he told the Times prior to the tape’s release. Clearly, Rocky and Yams had a deep knowledge of rap history and knew what they did and didn’t want to associate with. But after a decade in which Atlanta cemented itself as the hip-hop capital, a new generation of rappers revitalized the sound of LA rap, and ascendant Detroit and Flint artists made Michigan a teeming hotbed of talent, LLA's cherry-picking of sounds and slang feels less like a harbinger of doom for regional scenes in hip hop and more like the first glimpse of Rocky’s enduring desire to be an opaque, spongelike artiste -- which, to be fair, probably emboldened Travis Scott, Drake and other opportunists of the past decade.

On “Leaf,” Rocky sounds the same rapping about his contemporaries as he does Southern rap scenes: “They say I sound like André mixed with Kanye, little bit of Max / Little bit of Wiz, little bit of that, little bit of this, get off my dick.” No one in their right mind was really comparing him to André 3000 at the time, but “A$AP Rocky sounds like he’s from Houston” was a common take in 2011. Despite “Houston Old Head,” which DJ Burn One laced with a pitch-perfect Devin The Dude-esque beat, and “Purple Swag,” which garnered a remix from Paul Wall, Bun B, and Killa Kyleon, you’d really have to squint to mistake Rocky for a long-lost Screwed Up Click affiliate. While more pronounced than his predecessors, his a la carte flirtations with other regional scenes were anything but new in New York.

Just in the 15 years prior to Rocky’s debut you have Jay-Z heading south for “Big Pimpin’,” G-Unit freestyles over Geto Boys and Slum Village beats, 50 Cent becoming the protegé of one of the godfathers of West Coast rap, and from Rocky’s backyard in Harlem, the Diplomats developing the A$AP Mob syllabus 10 years prior. Rocky’s onetime collaborator SpaceGhostPurrp has alleged that Rocky bit his entire style, but Dipset’s takes on Three 6 Mafia’s “Sippin’ On Some Syrup,” Master P’s “Bout It, Bout It Pt. II,” and Bone Thugs’ “1st Of Tha Month” deflate Rocky’s bid at pioneer status on their own, especially his claim of being the only one in his neighborhood “on his Bone shit.” Remember that kid in middle school who thought he was hot shit because he “discovered” Pulp Fiction from an older sibling?

The hodgepodge of regional signifiers was what critics and New York hip-hop media latched onto, but Rocky saying “trill” in a pitched-down voice was no more responsible than Anna Trill for his music garnering their attention. LIVE.LOVE.A$AP became the launchpad for Rocky and the rest of the Mob’s careers because it had bangers. Oddly enough, its best songs are the ones that sound least like '90s Southern rap. If you want the simple answer as to why Rocky sounded so ineffably cool on the tape, it’s Clams Casino.

Clams, a New Jersey native who was already a known entity for his Lil B collaborations and his phenomenal Instrumentals release in March 2011, delivered the definitive performance of his career on the third of LLA that he produced. With three of the first four tracks and two of the last four on the tape, he effectively bookends it, those prestige sequencing spots making it clear that Rocky, his team, and his label were well aware how hard “Palace,” “Bass,” “Wassup,” “Leaf,” and “Demons'' went. Rocky’s lyrics and vocal processing aside, these songs sounded like no bygone region or era of hip-hop, instead defining that brief window when “cloud rap” was a buzzword. Clams’ beats paired wispy vocal samples with blown out drums and cavernous bass, their majesty distracting from Rocky’s shortcomings as a lyricist and amplifying his gift for earwormy flows, melodies, and in the case of “Demons,” swagged-out takes on Kid Cudi’s lonely stoner archetype.

This isn’t to say that nothing else on LLA slaps -- the Schoolboy Q-assisted “Brand New Guy” is an all-time great boisterous bro-out session, and “Kissin’ Pink” offers the dual threat of a luxuriant Beautiful Lou beat and a tantalizing first glimpse of A$AP Ferg’s talents -- but those Clams tracks were, and still are, world-beaters. The tape’s low points, such as the Big Sean-esque punchline-fest closer “Out of This World” (“I'm fly like I never left/ You's a lie, like fly without the letter F”) already sounded dated upon arrival, casting the Clams tracks in even sharper relief. It’s unfortunate that LLA had only been available in Datpiff bitrates for the past 10 years, but thankfully that was rectified today with an anniversary reissue for streaming services.

There’s a new Clams Casino collaboration, “Sandman,” on the reissue, but apart from a handful of relatively forgettable tracks strewn across the 2012 A$AP Mob tape, Rocky’s 2013 debut album, and Clams’ own 2016 album 32 Levels, Rocky and Clams haven’t exactly maintained the symbiotic relationship displayed on LLA. Rocky has continued to get artsier on his own terms, but at least for me, his attempts at getting trippy have never eclipsed the Clams-assisted swaggy headfucks of his first full-length release.

In 2011, Rocky was hellbent on convincing us that he was hip-hop’s first content aggregator, the first New York rapper with an internet connection. While he’s never abandoned that love for Houstatlantamemphis — note how giddy he sounds rapping over a well-worn Three 6 sample (also flipped by Dipset!) on the new Maxo Kream album — he’s recently seemed more interested in selling us on the supposedly “psychedelic” or “experimental” qualities of his music, rather than its regionless-ness. At Long Last A$AP and Testing both have their moments, but they’re far from the perception-altering culture-shifters Rocky hawks. His talent lies, as it has from day one, as a skillful curator, a catchy songwriter, and above all, a pretty motherfucker. Like dude, you’re dating Rihanna but you might never make Bitches Brew. How many of us can even check one of those two boxes? Just embrace being a trippy himbo -- it worked for Matt McConaughey!